You Can’t Go Home Again If You Never Left

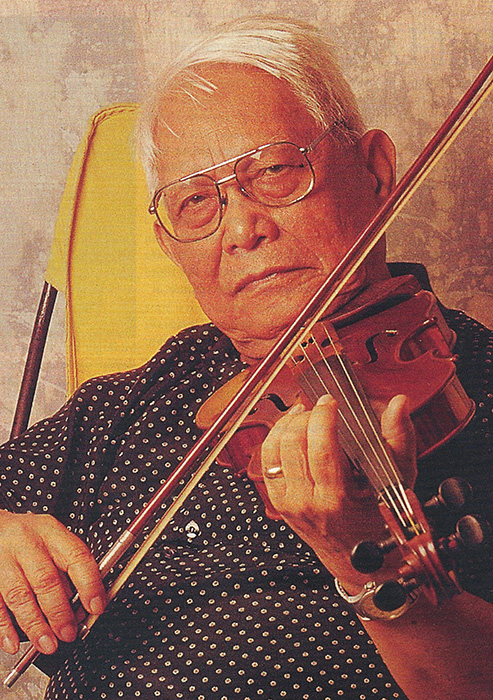

/N.V.M. Gonzalez (Photo by Ellen Tuyay)

Sharing the jeepney are two balikbayan Filipinas from New York, who are laden with pasalubong (gifts) and other, less visible, baggage. The women can’t take their eyes off the bucolic village scenery, the children playing by the rice fields, the palm trees leaning out over the shore. Across choppy seas, Romblon shimmers in the blue distance.

“Growing up here I didn’t appreciate this place,” says one of the women. “Now I just want to come back and leave the rest behind.”

In the Filipino way, the women have already exchanged genealogical information with Gonzalez, whom they recognized.

“How long since you’ve been back?” one woman asks the writer, who taught at U.S. universities for 15 years.

“I never left home,” Gonzalez replies, with raised eyebrows and a wide, open-mouthed smile, sharing in the surprise and delight of his own answer. Indeed, despite his long, often expatriate career, Gonzalez has kept his focus fixed firmly on the Philippines and the lives of Filipinos.

“He points out that anyone searching for Filipino culture today doesn’t look in Manila, but in the provinces, where the richest indigenous styles are found among peoples such as the Ifugao, the Bagobo or the Maguindanao.”

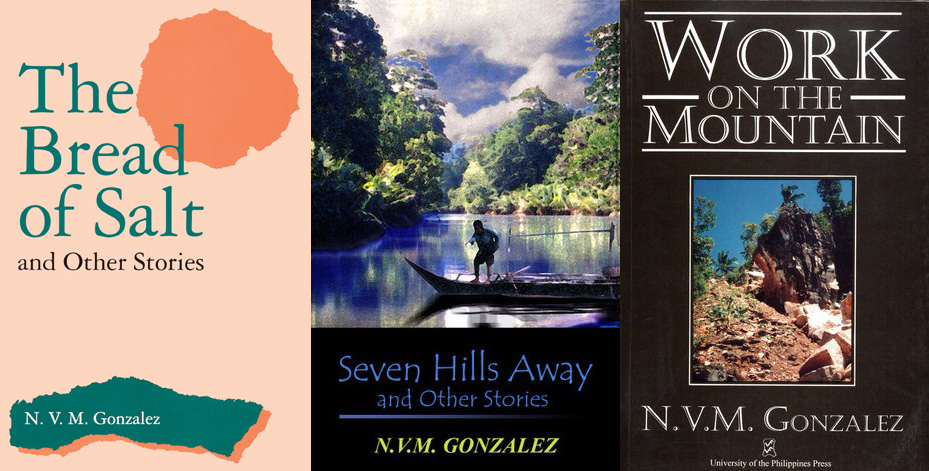

His second book, Seven Hills Away, a collection of stories, won him a creative writing fellowship to Stanford in 1949, the first of his many trips to Asia, Europe and the United States. In 1950 Gonzalez began teaching at the University of the Philippines (UP). He started teaching abroad in 1968, with visiting professorships at the University of California at Santa Barbara, UCLA, UC Berkeley, the University of Washington and other schools.

In 1983 he retired as Professor Emeritus from California State University at Hayward and returned to teach at UP. Gonzalez calls his long absences from the Philippines “merely physical, a concession to geography.” He still maintains a residence in California, where he occasionally visits.

Now, after all the travels, after three novels and five collections of stories, after simultaneous careers as novelist, journalist, critic and teacher, after literary prizes and honorary degrees, Gonzalez has returned to the scene of his childhood and the earliest setting of his fiction. Romblon is a small town on a small island that is best known for its marble.

Gonzalez points to the northern end of the long, semi-circular harbor. “You see that cemetery out at the point,” he asks. “I made my first peso by playing a violin all the way there for a Chinese funeral.” His remark recalls the young violinist in The Bread of Salt, a Gonzalez story in which the 14-year-old narrator tries to woo the niece of a rich Spaniard. The main action of the story takes place at a wedding party where the young musician plays. Later would Gonzalez point out the site of the Spaniard’s mansion. It’s clear that the balcony in the wedding party in The Bread of Salt, will endure far longer than the actual structure that inspired it.

One of his stops during this hometown visit is at Romblon High School. A large group of students and faculty turned out to welcome him with songs and refreshments. Teachers introduce themselves. Gonzalez asks one member of the English department if she enjoys teaching English.

“I have no regrets, even though it’s a second language.”

“You have an English department and a Pilipino department. But Tagalog is a second language and English a third,” Gonzalez says. “Don’t you want a Romblon department? Your language defines your world, including the history of our enslavement by the English.”

Gonzalez and his wife, Narita (Photo by Ellen Tuyay)

Gonzalez is passionate about “the language issue.” In a recent collection of essays and lectures, Work on the Mountain he expresses regret that English became the official language of the Philippines. He describes his difficulty as a young writer using “the borrowed language” of English to relate events of provincial life in the Philippines.

“The learning process could hardly be called slight; we had to do everything in a received language, every single word truly an alien presence.” Gonzalez has been misunderstood inside and outside the Philippines. Tagalog writers have accused him of pandering to Western taste. His American publisher considered his stories of daily provincial life to be folklore.

But ultimately his struggle—to appropriate the language of the colonizer, to shape it to his own use and to encourage writers in Pilipino—has been successful. The tables have turned. “Not only has writing become democratized but it has also been indigenized,” writes Gonzalez, in Work on the Mountain.

He points out that anyone searching for Filipino culture today doesn’t look in Manila, but in the provinces, where the richest indigenous styles are found among peoples such as the Ifugao, the Bagobo or the Maguindanao. “It’s no small irony that it has been folk such as these, who may be described as the most un-Filipino, that have supplied those elements in the national culture which have been much valued as distinctly Filipino.”

To his Romblon High School audience Gonzalez says, “The way to keep your inner light alive is never to lose your native roots.”

Do these students and teachers—many of whom have never ventured beyond this small island—believe their well-traveled guest? His message contradicts the national education policy. The Romblon teachers complain that the Department of Education, Culture and Sports imposes national textbooks on them without any regard to local needs or desires.

“How were you able to use Romblon in your stories?” one student asks.

“It was the first place, the only place I knew,” Gonzalez replies. “Others have choices, so they write things nobody reads.” Again his eyebrows arch and his smile widens, inviting laughter and recognition.

He’s here to encourage the students. Romblon lies far from Manila, San Francisco and New York, yet Gonzalez has gone the distance and returned to tell them to value what they had and what they knew.

As the meeting draws to a close, a student reporter from the school paper, The Marble, asks Gonzalez, “What’s your main purpose in coming here?“ Everyone laughs. Her eyes are wide but don’t see.

Later, after leaving the school, Gonzalez and friends will circumnavigate the island by jeepney. Great green hills, faraway bays and dozens of marble quarries mark the passage. The road winds up wooded slopes and back down to the sea, making the island seem larger than it is.

Gonzalez has a special, personal interest in the marble quarries. A photograph he took of one Romblon quarry appears on the cover of Work on the Mountain, emphasizing the connection he sees—as the book’s title implies—between writing and mining. “All we do as writers is carve away at the mountain of reality and then pass on the pick and shovel to the next in line,” he says. Gonzalez calls himself “a geologist of the imagination.”

At 81, having added three books in the past two years to his body of work, Gonzalez defies the usual pattern of peak and decline. He appears to be gathering momentum into advancing age, learning and growing and laughing while others grow old. Beneath his shock of white hair his eyes sparkle with humor and curiosity. He scrambles spryly on and off pump boats and jeepneys, equally at home in tropical rain forests or the halls of academe.

Books by N.V.M. Gonzalez, The Bread of Salt (bibliovault.org), Seven Hills Away (goodreads.com) and Work on the Mountain (goodreads.com).

His recent books demonstrate that in his travels as a visiting professor or cultural ambassador for the Philippines, or as a prolific reader in various literatures, Gonzalez has always been on the lookout for insights that might inform the dilemma of the Filipino artist. His new books mix literary criticism and autobiography with history and cultural analysis to render a rich, complex portrait of Philippine literature in this century. (Besides Work on the Mountain, 1995, his latest books include The Novel of Justice and The Grammar of Dreams, both published in 1996).

The jeepney pauses by the sea. A soft rain begins to fall. Gonzalez recounts a meeting of writers and diplomats he attended at Malacañang Palace. One senior official told Gonzalez that the Philippines needed a Nobel Prize.

“Why?” Gonzalez asked the man. “Do you read fiction? Can you even name one book that I have written?”

The official blinked and stammered.

“We won’t get the Nobel Prize until you start reading,” Gonzalez declared. “You’re the reason the Philippines doesn’t have the prize.”

The vision of Gonzalez upbraiding an ignorant, self-important government official makes his friends smile. The functionary’s typical hypocrisy aside, Gonzalez believes that fiction isn’t just relevant to modern life. It’s crucial.

“The art and craft of the storyteller is central to our nationhood,” he writes in Work on the Mountain. “Rare is the nation with a novelist for a national hero. Thus, to know what novels are, what their writing entails and what their writers ask of us as readers, is for the individual as well as, perhaps, for the nation, a decisive step toward self-knowledge.” Of course, Jose Rizal is the novelist hero Gonzalez alludes to, the writer whose novels—in the language of the colonizer—brought about martyrdom and revolution.

Gonzalez is upbeat about the future of Philippine literature, which has proven tenacious despite long oppression, drastic political changes and chronic critical neglect. N.V.M. Gonzalez and Philippine literature appear to have come of age together, with a strong burst of energy as this century ends.

Leaving Romblon, Gonzalez and his party boards an overnight ferry for the journey back to Batangas and Manila. Back to schedules and traffic. The departing travelers can each return in memory to their own versions of Romblon anytime, except for N.V.M. Gonzalez, who never left.

Reprinted from Filipinas Magazine, January 1997

James McEnteer was Visiting Fulbright Professor at the University of the Philippines, Diliman, in 1994-95. He lives in Mindanao.

The Tomato Game

By N.V.M Gonzalez

(Reprinted with permission from the N.V.M. Gonzalez Estate)

Dear Greg,

You must believe me when I say that I've tried again and again to write this story. The man remains vivid in my memory, alone in his clapboard shack in the middle of a Sacramento Valley tomato field. It is a particularly warm Sunday, in the height of summer. Also, it is the year of my miserable lectureship at Transpacifica University, which caters to the needs of such an industry. Well, it's all because of the ethnic pot. A certain number of offerings oriented toward the minorities, and the university becomes entitled to certain funds. You have read, in the papers how Transpacifica gave an honoris causa to a certain personage – a prestigious thing to do – which is that, indeed. Look up the word in the dictionary; I do mean what I say. But to return to that summer when, in a fit of nostalgia, I had agreed to go with Sopi (you must know him, of course) to look up some countrymen who might be into the national pastime of cockfighting. It is illegal here, hence a San Francisco Chronicle headline – "Transpacifica Lecturer in Bloody Bird Tourney Raid" – did not seem at all unlikely.

We risked it anyhow and got much more. As in myth, the signs were all over: the wooden bridge; the folk of the road; the large track all around as which earlier had been a tomato field; the harvesting machine to one side of the field, a men-acting hulk, indicating how rich the crop had been – you can see how hard I try. Would that I could have it in me to put all this together.

I can tell you at this juncture that Alice and her young man must be somewhere here in America. So is the old man, I'm positive. The likes of him endure.

"To such a man," Sopi said to me afterwards, "pride is of the essence. He is the kind who tells himself and his friends that as soon as he is able – in twenty, thirty years, say – he will return to the Islands to get himself a bride. How can you begrudge him that?" But it's the sort of talk that makes me angry, and at the time I certainly was.

I am now embarrassed, though, over how we behaved at the shack. We could have warned the old man. We could have told him what we felt. Instead, we teased him.

"Look, Lolo," Sopi said. "Everything's ready, eh?"

For, true enough, he had furnished the clapboard shack with a brand-new bed, a refrigerator, a washing machine – an absurdity multiplied many times over by the presence, Sopi had noticed earlier, of a blue Ford coupe in the yard. "That's for her..." Sopi had said.

We enjoyed the old man immensely. He didn't take offense – no, the old man didn't. "I've been in this all along, since the start. Didn't I make the best deal possible, Lolo?"

"Ya, Attorney," the old man said.

"He could have stayed in Manila for a while, lived with her, made friends with her at least," Sopi turned to me as if to tell me to keep my eyes off the double bed. The flower designs on the headboard were tooled on gleaming brass. "But his visa was up. He just had to be back. Wasn't that the case, Lolo?"

"Ya, Attorney. Nothing there any more for me," the old man said.

"And this taxi-driver boy, is he coming over too?"

Sopi, of course, knew that the boy was – bag and baggage, you might stay.

"That was the agreement," the old man said. "I send him to school – like my son."

"You know, Lolo, that that will never do. He's young, he's healthy. Handsome, too."

"You thinking of Alice?" the old man asked.

"She's twenty-three," Sopi reminded him. I figured the old man was easily forty or forty-five years her senior.

"Alice, she's okay. Alice, she is good girl," said the old man. "That Tony-boy... he's bright boy."

As an outsider, I felt uneasy enough. But the old man's eyes shown with fatherly satisfaction. There was no mistaking it. Wrong of you, I said to myself, to have cocksure ideas about human nature.

I saw Sopi in the mirror of my prejudices. He was thin but spry, and he affected rather successfully the groovy appearance of a professional, accepted well enough in the community and, at that, with deserved sympathy. Legal restrictions required that he pass the California Bar before admission to the practice of law amongst his countrymen. Hence, the invention which he called Montalban Import-Export. In the context of our mores he was the right person for the job the old man wanted done. Alice was Sopi's handiwork in a real sense, and at no cost whatsoever. Enough, Sopi explained to me, that you put yourself in the service of your fellows. I believed him. He knew all the lines, all the cliches.

I could feel annoyance, then anger, welling up inside me. Then, suddenly, for an entire minute at least, nothing on earth could have been more detestable than this creature I had known by the tag "Sopi." Sophio Arimuhanan, Attorney-at-Law, Importer-Exporter (parenthetically) of Brides – and, double parenthesis please, of brides who cuckolded their husbands right from the start. In this instance, the husband in question was actually a Social Security number, a monthly check, an airline ticket.

And I was angry because I couldn't say all this, because even if that were possible it would be out of place. I didn't have the right; I didn't even understand what the issues were. I was to know about the matter of pride later, later. And Sopi had to explain. It was galling to have him do that.

But at that moment I didn't realize he had been saying something else to me. "This Alice – she's hair-dresser. She'll be a success here. Easily. You know where we found her? Remember? Where did we find her, Lolo?"

The old man remembered, and his eyes were smiling.

"In Central Market. You know those stalls. If you happen to be off guard, you can get pulled away from the sidewalk and dragged into some shop for a – what do you call it here? – a blow job!"

The old man smiled, as if to say, "I know, I know…"

"We tried to look up her people afterwards. Not that this was necessary. She's of age. But we did look anyway. She had no people any more to worry over, it turned out," Sopi went on. "She did have somebody who claimed to be an aunt, or something – sold tripe and liver at the meat section. She wanted some money, didn't she, Lolo?"

"Ya, ya," the old man said. "All they ask money. Everyone." And there must have been something exhausting about recalling all that. I saw a cloud of weariness pass over his face.

"But we fixed that, didn't we?"

"Ya, ya," said the old man.

"Then there was the young man. A real obstacle, this taxi-driver boy. Tony by name," Sopi turned to me, as if to suggest that I had not truly appreciated the role he played. "We knew Tony only from the photograph Alice carried around in her purse. But hewas as good as present in the flesh all the time. The way Alice insisted that the old man take him on as a nephew; and I had to get the papers through. Quite a hassle, that part. It's all over now; isn't it, Lolo?"

"Ya, ya," said the old man. "I owe nothing now to nobody. A thousand dollars that was, no?"

"A thousand three hundred," said Sopi. "What's happened? You've forgotten!"

"You short by three hundred? I get check book. You wait," said the old man.

"There's where he keeps all his money" Sopi said to me.

He meant the old bureau, a Salvation Army piece against the clapboard wall. Obviously Sopi knew the old man in and out.

"No need for that, Lolo. It's all paid for," he said.

The old man's eyes brightened again. "I remember now!"

"Every cent went where it should go," Sopi said to me.

"I believe you."

"So what does her last letter say?"

"They have ticket already. They come any day now," the old man said.

"You'll meet them at the airport?"

"Ya."

"You've a school in mind for Tony-boy?"

And hardly had I asked then when regrets overwhelmed me. I should know about schools. The Immigration Service had not exactly left Transpacifica alone, and for reasons not hard to find. They had a package deal out there that had accounted for quite a few Southeast Asian, South Vietnamese, and Singaporean students. Filipinos, too. Visa and tuition seemed workable as a combination that some people knew about. A select few. It was a shame, merely thinking of the scheme. But, strangely enough, my anger had subsided.

"Ya," the old man then said. Tony had a school already.

"That's why I wanted you to meet the old man," Sopi said. "Help might be needed in the area – sometime. Who can say?"

"You don't mean Transpacifica, do you?"

"That's your school … right?"

"How so?" I asked.

"Eight hundred dollars a year is what the package costs. The old man paid that in advance. It's no school, as you know."

"I only work there. It's not my school," I said.

All right, all right," Sopi said. "There's all that money, and paid in advance, too . . . so this 'nephew,' bogus though he might be, can come over. You understand. We're all in this."

I began to feel terrible. I wanted to leave the shack and run to the field outside, to the tomatoes that the huge harvesting machine had left rotting on the ground. The smell of ketchup rose from the very earth. If it did not reach the shack, the reason was the wind carried it off elsewhere.

"Ya, they here soon," the old man was saying. "Tomorrow maybe I get telegram. Alice here, it'll say. Tony, too. You know I like that boy. A good boy, this Tony. Alice... me not too sure. But maybe this Tony, a lawyer like you some day. Make plenty money like you," said the old man to Sopi.

"Or like him," said Sopi, pointing to me. "Make much-much more, plenty-plenty . . ."

The old man seemed overjoyed by the prospect, and I had a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach. The old man had trusted Sopi all along, and you couldn't but believe that he had seen enough models of Tony before.

We had come that Sunday, as I started to tell you, to see if we could watch a cockfight. When we left the shack finally, Sopi said to me, "To think that that old man hasn't even met the boy."

As we drove down the road toward the fork that led to the wooden bridge, the smell of ripe tomatoes kept trailing us. That huge machine had made a poor job of gathering the harvest; and so here, Greg, is perhaps the message.

BESTS ...

1972

(From The Bread of Salt and Other Stories, University of Washington Press, 1993)