Shocked and Awed

/Book Review: The Battle of Marawi by Criselda Yabes

Pawikan Press, 2020.

Criselda Yabes’ “The Battle of Marawi”

During that war, the MNLF stood toe-to-toe against government troops, confident of its numbers, reach of influence, and firepower. The MNLF was also well-trained. One hundred of its commanders had received their combat education courtesy of East German trainers in Libya and Malaysian advisers in Sabah. Another hundred were in transit from Libya, this time schooled in anti-tank warfare.

Fortunato Abat's memoir, The Day We Nearly Lost Mindanao, hints at just how a surprised AFP nearly lost the Cotabato command. An upcoming recollection of Jolo's battle, by Agnes Shari Tan Aliman, who grew up there, also suggests similar difficulties. The Navy razed Jolo to the ground to force the MNLF to retreat, a perfect echo of the Americans' destruction of Vietnamese villages "to save them." Armor made the difference in Marawi and Cotabato.

To the field commander who was watching the fighting between the military and ISIS jihadis with Yabes, it was 1975 all over again, although with some variations. An outnumbered insurgent force (1,000 jihadis vs. an AFP force of 8,000) amply armed and knowledgeable of the terrain fought an 8,000-strong join task force for five months. And like 1975, the AFP was surprised not just by the jihadis' ferocity, but also by their vastly improved fighting capacities. Military armor was stopped by RPG rockets, raiding teams by high-powered rifles, and troop movement were monitored by drones.

Their leaders, the brothers Omarkhayyam and Abdullah Maute and the self-proclaimed "Emir of East Asia" Isnilon Hapilon were ideological fanatics who shunned the more secular MNLF and Moro Islamic Liberation Front's pragmatic Islamism. They entered the war looking forward to death (and having sex with 72 virgins); the two older groups just want to set up an Islamic republic.

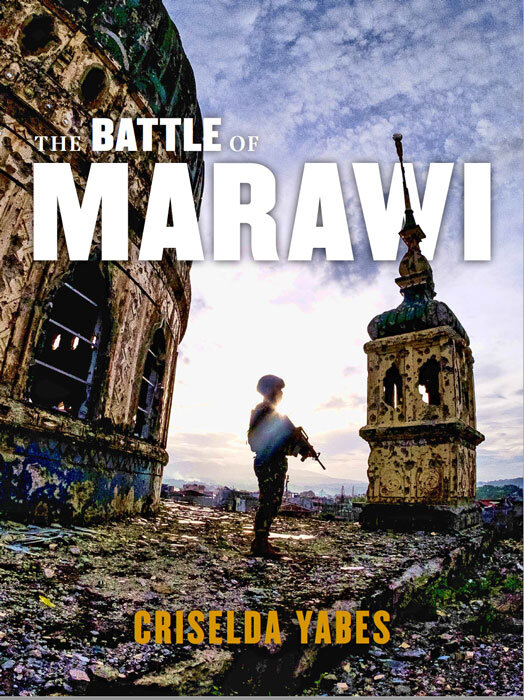

The battle-scarred city of Marawi (Photo by Criselda Yabes)

Had Yabes asked the field commander to elaborate, he would have recalled how shocked the AFP was in its lack of preparedness in 1975 to explain 2017. The Battle of Marawi's opening chapters are full of stories of bungled operations, missed opportunities, and conflicting tactics, which accounted for the length of time it took the AFP to finally eliminate the "Maute Group."

When the botched arrest of Hapilon by units of the Light Reaction Regiment triggered the jihadis' seizure of central Marawi, one officer admitted to Yabes that "there were no government forces in Marawi." The first attempts to cross two bridges into central Marawi were repulsed. A visibly shocked Marine officer kept saying to Yabes, "Hindi namin alam ganoon katindi ang kalaban…Galing nila, ang galing nila (We didn’t know that the enemy was that strong…They were very good)." That shock of being forced to retreat for the first time in Marine history was not just because of the Mautes’ guns. Yabes adds that equally important was the devastating effects of inter-service rivalries. Yabes writes: "(The) Marine brigade commander was worried about his men getting overshadowed by the Army troops, consequently losing sight of the battle before them." The result was a big blow to Marine pride: 12 killed; several wounded – the first ever military defeat of an organization that is proud of its fighting prowess.

These failures were not just tactical problems. Embedded in that commander's remark was the singular flaw in the AFP's orientation. The military was not only an inward-looking force. It was also essentially an organization designed to run after countryside-based insurgencies. Even the Marines – supposedly the main fighting force of the Navy – were in the countryside running after communists. Urban warfare was never the AFP forte.

The Joint Task Force of Army, Scout Ranger, Light Reaction Regiment, Marine and Police Special Action forces, suffered devastating losses in its first forays. But the soldiers were also quick learners. And this would be shown in the acts of creativity that mitigated leadership boo-boos.

A wizened Light Reaction Regiment discovered how effective tear gas was in flushing out their opponents. The ISIS militants knew nothing about tear gas ("Nilalason yong hangin [They’re poisoning the air]," they complained over the radio). The least relied on units proved critical in battle. The Combat Engineering Battalion used its machines to break house walls and open pathways for the troops. Years of joint-training with their American counterparts paid off.

Service rivalries eventually gave way to effective on-the-ground collaboration. A commander wryly told his fellow Marines, "Wala ng pride-pride. Fried chicken na lang (Forget thinking about pride. Just fried chicken)," in explaining why it was time for them to learn from the house-to-house assault by a now wizened Light Reaction Regiment. The Marines even set up sniper positions for units of the much-maligned police force.

“The Battle of Marawi’s opening chapters are full of stories of bungled operations, missed opportunities, and conflicting tactics, which accounted for the length of time it took the AFP to finally eliminate the “Maute Group.””

Filipinos glued to telenovelas' Ruritarian romances will also be drawn to this book's tales of dedication and pain. Officers angrily implored God to speed up the reinforcements ("Lumingon ako sa langit, 'tang ina saan ka na? (I looked to the heavens. Sonofabitch, where are you?).” Or they called their wives to pray for them as they awaited another ISIS assault. Others refused to leave men who were wounded or killed, even as they felt cornered. One of the most poignant stories was that of Marine Pvt. First Class Gener Tinangag -- a 24-year-old father of a three-year- old -- who carried wounded comrades to safety in the Battle of Mapindi bridge, until he was killed by a sniper's bullet. Critics of the AFP are quick to portray it as a heartless, brutal institution. Yet, there they were, soldiers who agonized over whether to shoot ISIS child-soldiers or not ("There are young boys with guns. They are marching towards us. Sir, do we shoot at the kids?").

Yabes even has some sympathetic portraits of jihadis, including the Mautes’ mother, Farhana, but these will be for another review.

Yabes opens her book with an intimate portrait of the sniper who allegedly killed Abdullah Maute and his bodyguard. This Visayan learned his talent early when, as a kid, he became a slingshot artist. When he stalked Abdullah, with a weapon lent to him by American trainers (another story in itself), it was like going after the chickens and dogs outside the family home again. She also closes the book with another kid’s story, that of "the young unlettered boy" who became a military spy. He had become a father, but the innocence was still there in his "baseball hat and a faux Nike Air T-shirt."

The Battle of Marawi is Yabes' tenth book, a remarkable record not matched by any journalist or academic back home. It is also the first book on a Mindanao war written from the soldiers’ and rebels’ perspectives. For someone who grew up in northern Mindanao, this book brought back memories of the time the MNLF launched its war in Cotabato, Jolo, and Marawi.

Fact Sheet: In the 5-month siege, the AFP lost 168 men, and more than 1,400 were wounded. The Maute Group was wiped out: 978 killed and 12 captured. Thousands of Marawi residents were displaced by the war, and many have not returned to their devastated homes. Three years after, Marawi remains unrehabilitated despite promises of a quick recovery by President Rodrigo Duterte

Patricio N. Abinales teaches at the University of Hawaii-Manoa.

More articles by Patricio N. Abinales