When Russians Came to Tubabao

/By some strange alignment of the stars, two formerly opposing sides of Russian history will nearly collide in the Philippines this month. Russian refugees from the 1950s and their descendants, on the one hand, and Vladimir Putin, the first sitting Russian leader in history to set foot in the Philippines, on the other hand, are coming to the islands within ten days of each other for separate agendas.

[Ed Note: As we go to press, Vladimir Putin cancelled his Philippine trip.]

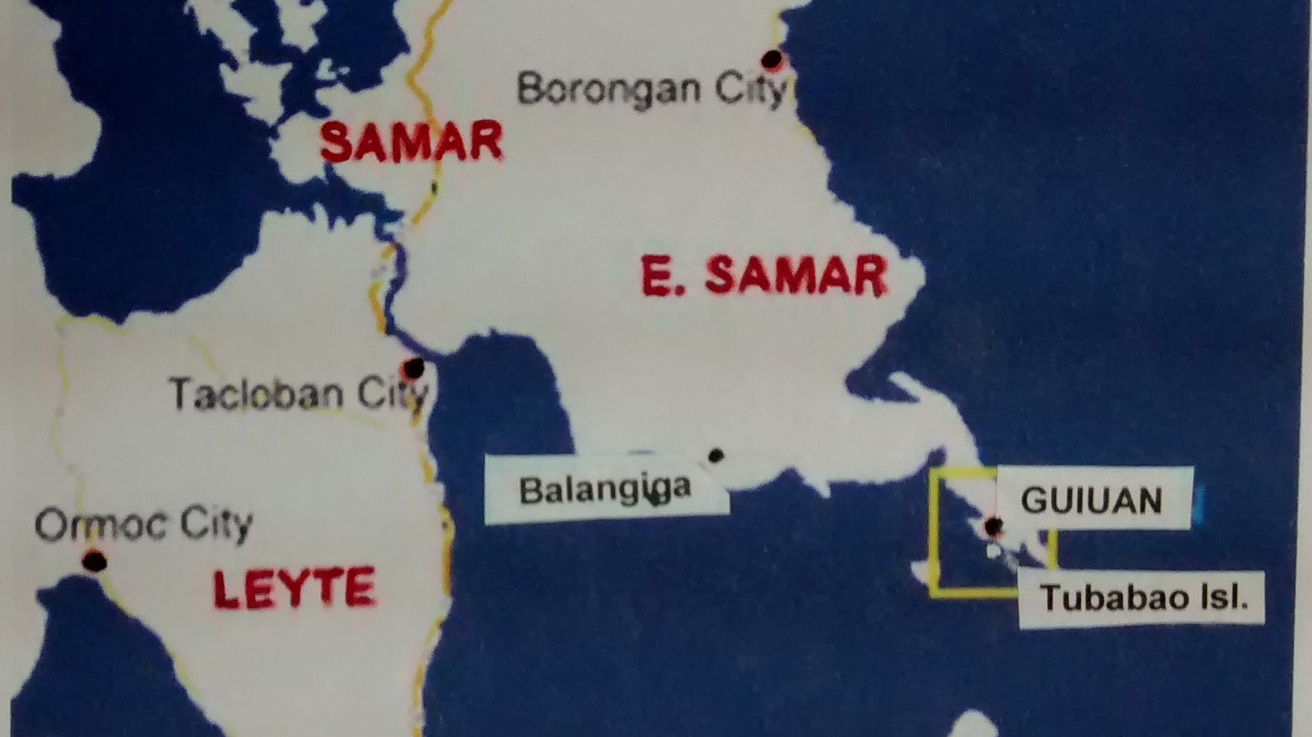

The 65th anniversary homecoming of White Russian refugees to Tubabao island (lower right) just off the Guiuan peninsula of Eastern Samar. The area is also known for the town of Balangiga where three controversial church bells were taken from the local church as booty after a bloody massacre on both sides of Philippine-American war.

White Russian refugees and their families are coming back for homecoming events to celebrate the (more or less) 65th anniversary of their escape from the advancing Chinese communist forces of Mao Zedong in 1948-1951 and temporary repatriation to a small Philippine island.

Vladimir Putin is coming for the APEC summit to be held in Manila with 20 other Pacific Rim-nations’ leaders. At the last APEC summit hosted in Subic Bay in 1996, Russia was not yet recognized as a member of the group.

What makes these events especially relevant at the moment are the heartbreaking images of swarms of Islamic refugees fleeing war-torn Syria and Iraq--reminiscent of the marielito “boat-people” from Cuba in the 1980s—seeking a haven in Europe. Two dozen advanced European countries have been nearly overwhelmed by the enormity of the numbers, not to mention the unanswered questions of whether Islamic refugees in such large numbers would fit into the new Christian lands and if sleeper terrorists have infiltrated their ranks.

For those not up on their Russian history, “White Russian” (WR) refers to those who swore allegiance to the Romanovs, the last monarchy of Russia, against the “Red Russians,” the Bolshevik revolutionaries who overthrew the Romanovs and eventually became the Soviets (and the Communist Party which Putin belonged to). Neither one should be confused with “Black Russian,”--which is not an Afro-Russian person but a mixed cocktail of Kahlua and vodka.

The ex-U.S. Army base on Tubabao Island, Samar, late 1940s, just before it was readied to accept some 5,000 White Russian refugees. (Source: M. Blinov Collection)

And what part does the Philippines play in all this? Seventy-five years ago, just before World War II engulfed three continents in flames, a small-scale operation to rescue some 1,200 European Jews was engineered by ailing Commonwealth President Manuel L. Quezon.

That 1939 Quezon-Jewish Evacuation is the far better known and documented rescue scenario compared with the WR chapter a decade later. Contrasted with the over-all horrors of World War II and the Holocaust, the Philippine-Jewish rescue ranks right up there with the righteous deeds of Oskar Schindler, Raoul Wallenberg, Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara in Lithuania, and a few others.

Flash forward ten years later to 1948-49. The Axis powers had been vanquished but in the meantime, lumbering and strife-torn China was about to fall to a new menace, the Communists. Communities of WRs along China’s eastern cities, mainly Harbin, Tientsin and Shanghai, were now facing the very same bleak prospects of survival that the European Jews did a decade earlier.

When the Chinese Communists, Moscow’s allies, took over, would they remain safe or would they be deported and handed over to the Soviets, in the same, shameful way that Great Britain betrayed 40,000 Cossacks and their families in 1945 in what is known as the Great Lienz (Austria) Betrayal?

In that incident, Great Britain, supposedly in compliance with the Yalta Agreement, all but turned over an estimated 40,000 Cossacks who had sided with the Nazis and fought against the Red Army, to Stalin's forces. Stranded in Austria and considered collaborators, the 40,000 were repatriated to the USSR where Stalin’s police went to work getting even, brutally torturing and executing Cossack leaders. The rest were sent to prison camps and hard labor. Could this happen again?

And there was greater urgency as well. The Nationalists, Chiang Kai-Shek’s government, had already abandoned the mainland and set up shop in Formosa (Taiwan’s old name). So Shanghai was left on its own, and Mao’s troops were advancing unopposed. Further, within the expatriate Russian community, there was a sudden, suspicious influx of people holding Soviet passports trying to “blend” in. The WR only saw them as Soviet spies infiltrating their ranks. The NKVD, the USSR’s military spy agency then, was mobilizing to mark and pick up recalcitrant WRs once the communists took over.

Enter the two-year old Philippine Republic and its second president, Elpidio Quirino, who was a secretary to Manuel Quezon sometime before the Jewish evacuation to Manila. Here was a chance for humanitarian history to repeat itself.

President Elpidio Quirino and Philippine Defense Forces brass paying a visit to Tubabao in October 1949.

For the Quirino administration, it was easy enough to accept and temporarily house a few thousand people because there were several abandoned bases around the country that the Americans had left behind just three years earlier, shortly after they granted independence to the islands. A few were in almost ready-to-move-in condition.

Before actual evacuation began in May 1949, an advance team from the Russian community in Shanghai came to Manila to iron out details with the Quirino administration and check out the recommended site. The base at Tubabao Island was found to be most habitable. There was a nearby airstrip, a fairly large town, Guiuan, for supplies and transit and Tubabao, being an island, was easy to secure. Just a few superficial touch-ups and the base was ready to receive new occupants.

But Tubabao was only going to be a way station for the WRs until they could join relatives in other countries. It was odd that cosmopolitan Manila was home to a few thousand Spaniards, Americans and a sprinkling of others of European origins (even Germans), yet not many of the Tubabao WRs considered staying and resettling permanently in the Philippines.

While indeed there was the matter of religious differences, and no direct connection between Slavic and the mix of Hispano-Filipino-American ways of life, resettling in Manila or even Cebu would certainly have been as challenging as resettling in new lands where many of them would be starting anew.

(There was one known Russian who settled in the islands, took a local bride, and whose son became Ronald Remy, a showbiz name in the late 1950s – 1970s. Remy’s real surname was Kookooritchin, and his father was a sailor with the Russian navy who came to the Philippines during the Quezon-Commonwealth era and settled in Bicol.)

Actor Ronald Remy (Source: video48@blogspot.com)

The new residents of Tubabao were without proper IDs. Their old tsarist passports were no longer valid and they preferred to remain “stateless” rather than carry Soviet papers. So the Quirino government and the International Refugee Organization, forerunner of what would become the United Nations Commission on Human Resettlements, issued special ID cards in the interim. Meanwhile, the USA, Canada, Chile and Australia passed special legislation to accommodate these special “stateless” individuals and worked with the relatives and Russian communities who would sponsor the displaced WRs.

Celebrating outdoor Orthodox services in a tropical setting—probably a first for a religion found mostly in the colder climes, circa 1950.

This past April, I had the opportunity to tag along with Kinna Kwan from Guiuan, who was in the U.S. to compile a recorded oral history project of the surviving Tubabao refugees. Her research was conducted under the auspices of the Quirino Foundation, which is underwriting a number of the 65th Tubabao/125th Elpidio Quirino con-celebrations. The handful of surviving ex-refugees we interviewed were but teenagers during their time in Tubabao and had vague memories of their stay.

As adolescents plucked from their surroundings in Shanghai, staying in Tubabao was a carefree experience for them. Like teenagers anywhere, their most enduring memories were making new friends or catching the eye of a new boy- or girlfriend, and just enjoying the tropical interlude, however long that lasted. The uncertainty of where their continuing voyage would take them, they left to the elders. But all of them were extremely grateful for the reprieve the 1950s Philippines offered when no one else would take them. They welcomed us into their homes like long-lost relations.

Group photo of White Russian kids in Tubabao, enjoying the tropical sunshine. The surviving kids who were scattered to the USA, Australia, South America and Canada are seniors today. (Source: http://sergoyan.coffeetownpress.com)

As part of the joint 125th Quirino Birth Anniversary and 65th Anniversary Homecoming to Tubabao celebration, the Quirino Foundation has lined up the following activities:

November 14 - Ayala Museum, Makati City, Manila, 4-6:30 p.m.

Lecture by Ms. Natalie Sabelnik (President of the Congress of Russian Americans) and Dr. Tatiana Tabolina (Russia Academy of Sciences); and Russian Concert by Mr. Nikolai Massenkoff, World Celebrated Russian Folk Singer.

November 16 - 125th Birth Anniversary of President Elpidio Quirino and Culmination of the Arts Festival

November 17 - Interaction with Former Refugees

Representatives from high schools and colleges in Guiuan will be given the opportunity to interact with former refugees as they share their memories of their life in Tubabao Island.

Launch of the Green Wall Project in Tubabao Island

The Green Wall is a sustainable project spearheaded by the Municipality of Guiuan and the Quirino Foundation to plant mangroves, bamboo and coconut trees to create a “green wall” along the coasts of Tubabao. The objective is to mitigate risks of natural disasters, as well as to provide livelihood to the community.

November 18 - “Salamat Pangulong Quirino!”: A Homecoming of the White Russians to Tubabao Island and Unveiling of Historical Markers

Ceremonies will be attended by the former refugees, the Quirino family, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Moscow Patriarchate delegation, Russian Embassy in the Philippines, the Congress of Russian Americans and other organizations.

Today, with the old Stalinist Soviet Union officially dismantled, the old animosity between the Whites and whoever still identify themselves Reds seems to have waned. In 2012 a plaque of gratitude was placed in Guiuan by the Russian Embassy in Manila, although the survivors of the refugees never fully endorsed the gesture.

The plaque reads: “Nurture In Memory (Sic) Kindness Of The People Of The Philippines Who In 1949-1951 Provided On The Island Of Tubabao, Safe Shelter To Russian Nationals Destined To Survive Hardships Far From Motherland. With Sincere Gratitude, Embassy of the Russian Federation In The Republic of fhe Philippines. Year 2012.”

In 2013, in the aftermath of the destruction caused by Yolanda/Haiyan in the eastern Visayas, the Russian Federation immediately dispatched two giant jet-loads of supplies, medicines and medical personnel to Tacloban and to Samar.

One of the two Russian Ilyushin-76 cargo planes, which Moscow quickly sent to the Visayas in the aftermath of Yolanda/Haian in 2013. It landed in Tacloban with Russian doctors, medical and emergency supplies.

This month, however, security considerations notwithstanding, it remains to be seen if Vladimir Putin will make a historic, unscheduled visit to Tubabao-Guiuan and be “welcomed into the surviving WRs’ heart.” He is, after all, an ex-KGB operative. Will the warm, gentle breezes of our islands work their tropical magic to heal an old wound?

Acknowledgments:

“The Saga of the White Russian Refugees in the Philippines,” by Ricardo Suarez Soler

Kinna Kwan and the Quirino Foundation

“The Tarasov Saga” by Gary Nash

Myles Garcia is a retired San Francisco Bay Area-based writer. Myles just won a 2015 Plaridel Award (Best Sports Story) for “Before Elorde, Before Pacquiao, There Was Luis Logan,” here on Positively Filipino (November 17, 2014). He is also a member of the ISOH (International Society of Olympic Historians) and has written for the ISOH Journal. There are a book about the mess the Marcoses left behind in "30 Years Later..." and a play, "Murder á la Mode," nearing completion.

More articles by Myles A. Garcia