What languages do you speak?

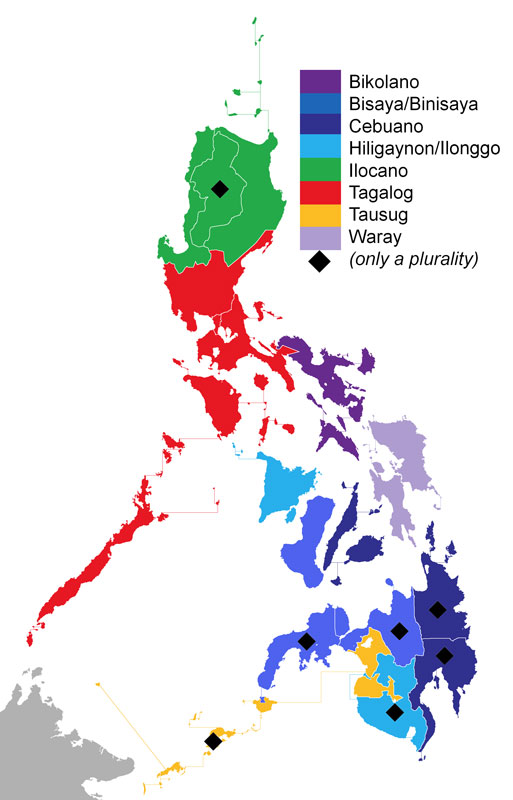

/Languages spoken per region (Source: Wikipedia)

Introductions are supposed to be quick, so imagine the looks that Zeena will receive if she mentions three places as country of origin. She simply says, “I’m from Canada,” because that’s where she goes home during holidays, even though that’s only half of her story.

My classmates and I once helped another classmate move into another apartment. We met the landlady who exclaimed when she saw our different colors, “How interesting that you come from different countries!” Instead of asking the usual question, she asked each one of us as she shook our hands, “What languages do you speak?” Zeena liked the question so much better than being asked “Where do you come from?” It is the kind of question that does not anchor a person to a particular place. Rather, it invites conversations on the stories of the person.

“Younger immigrants are demonstrating greater connectedness to their parents’ country of origin without necessarily diminishing the ties they have to their country of residence.”

“Where do you come from?” is also a common question in an archipelago like the Philippines. The people living in Metro Manila could have come from more than a thousand different islands. But we are also a country with more than 180 living languages, and I believe it’s more fitting and interesting to ask, “What languages do you speak?” Imagine an answer that says, “My family and I speak Kankana-ey at home. I speak Ilocano when I’m in town. I speak Ilocano and Filipino in conversations at work, and I use English in emails.” All these things are not captured when the person says, “I am from Baguio.”

Perhaps if we ask “What languages do you speak?” we will actually get to understand that Bisaya or Binisaya is not a single language. We will hear Hiligaynon, Kinaray-a and Waray. We will hear the language Cuyonon and not only the place Palawan. To put it further, imagine three people coming from one province, say Zambales, and they might mention three different languages when you ask them what language they speak at home. The first speaks Ilocano, the second Sambal, and the third Tagalog.

Outside of the Philippines, consider the Filipino diaspora where Filipinos are scattered all over the world, from Iceland to Zimbabwe. In many ways, Zeena’s story of straddling several countries is not unusual. It is the story of millions of Filipinos. There are more than three million Filipinos in the US alone. They consider themselves Americans, and in equal terms Filipino. Numerous studies on transnational lives show that there is a marked difference between the new generations of immigrants from the older ones. Younger immigrants are demonstrating greater connectedness to their parents’ country of origin without necessarily diminishing the ties they have to their country of residence; they understand much more than their parents’ generation and the generation that came before their parents, that embracing one identity does not replace the other. It is not surprising that the University of Hawaii at Manoa recently started offering a degree on Ilocano language. So why are we still stuck with the question “Where do you come from?” when a lot of us are not anchored to a single place anymore?

I read somewhere that we should avoid “Where do you come from?” as our first question to a new acquaintance. We should not assume that a person of a different color than the mainstream is not a native of the place. After all, what is considered mainstream is becoming more difficult to define. More than that, a burning issue of our time is the increasing closing of borders, so that “Where do you come from?” takes on a nasty connotation. Questions such as “What languages do you speak?” become resonant because they affirm the rich linguistic diversity and cultural background that people bring with them.

We need new questions to capture new situations.

Dayyuman Marie Ngoddo works with an NGO during the day and writes at the night. She hopes for a time when the situation is the reverse.

More from Dayyuman Marie Ngoddo