We Stand on Their Shoulders, Part 4

/MEDIA

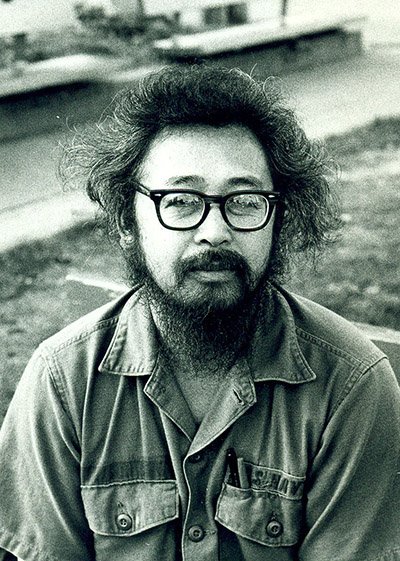

Alex Esclamado, Publisher

Alex Esclamado

Alex Esclamado studied law at the Far Eastern University in Manila. After he passed the bar in 1955, he worked for President Magsaysay’s Land for the Landless Program, which saw the distribution of land in Mindanao to the landless peasants in Luzon who had turned their backs on the Huk rebellion.

In 1961, Esclamado moved to San Francisco to be the chief U.S. correspondent for Manila Chronicle. He founded the Philippine News out of his home in the Sunset District of San Francisco, California. The newspaper reported on the activities of the growing Filipino community and advocated for its interests. When the Delano farm workers went on strike in 1965, Esclamado organized a food caravan, gathering canned goods and driving to Delano to distribute them to the farm workers. He also worked with Rep. Philip Burton to pass the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which increased quota of countries like the Philippines from 50 a year to 20,000 a year. Esclamado organized the Filipino American Council of San Francisco, a coalition of dozens of Filipino community organizations that would help newly arrived immigrants and senior citizens. He was also an early supporter of Filipino WWII veterans, lobbying Congress to grant them U.S. citizenship, which eventually happened on October 1990.

He was a vocal opponent of former President Ferdinand Marcos after his government declared martial law in 1972. Advertisers were asked to boycott Philippine News, and it almost caused the paper to close. The Esclamados borrowed money from friends and mortgaged their properties as collateral for loans. Philippine News continued to expose the abuses of the Marcos administration and refused an offer of $10 million to sell the paper.

In October 1986, Esclamado was recognized as the only Filipino American recipient of the congressionally sponsored Ellis Island Medal of Honor Award. On May 9, 1989, President Corazon Aquino bestowed on Esclamado the Philippine Legion of Honor. Excerpt of the award read: “For his distinguished and outstanding service to the country during the past 20 years. Often a lone voice in the United States, he relentlessly championed Philippine freedom and democracy without regard for personal safety in the face of the threatening might of the dictatorship.”

In an effort to unite the divided Filipino American community, the National Federation of Filipino American Associations (NaFFAA) was formed in 1997 in Washington, D.C. More than 3,000 Filipino American associations joined, and Esclamado was elected the national chair. NaFFAA now has more than a dozen chapters all over the U.S. NaFFAA and GMA International annually grant the Alex Esclamado Memorial Awards for Community Service to organizations involved in youth affairs, education, senior citizens, women, health, immigration and human rights, entrepreneurship, arts and culture, aid to the Philippines and civic involvement.

Alex Esclamado died on November 12, 2012 in his hometown of Padre Burgos, Southern Leyte of pneumonia, after a ten-year battle with Parkinson’s disease. He was 83 years old.

Francisco “Corky” Flores Trinidad

Francisco “Corky” Flores Trinidad (Source: Achetron)

Better known by his pen name, Corky, Trinidad was born in Manila and became an editorial cartoonist and artist. He comes from a family of journalists. His father, Koko Trinidad was a broadcaster while his mother, Lina Trinidad was a columnist. His cartoons appeared at the Philippines Herald, but he fled the country during the dictatorship of President Marcos.

Trinidad became the first Asian and Filipino editorial cartoonist to be syndicated in the United States and the only Asian American and Filipino American editorial cartoonist at a major U.S. metropolitan newspaper. As such, his work has appeared in non-U.S. periodicals such as the International Herald Tribune, Denmark's Politiken Daily, the Buenos Aires Herald, the Manila Chronicle, and the now-defunct British magazine Punch. Since 1969, his works have appeared in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

His comic Nguyen Charlie was carried by the United States Army's Stars and Stripes newspaper, and each day's strip was eagerly awaited by the GIs in South Vietnam. He later drew two more comic strips, Aloha Eden and Zeus. He also found time to teach cartooning at the University of Hawaii.

Trinidad's editorial cartoons were critical of Hawaii politicians as well as the Marcos dictatorship. A collection of his cartoons chronicling Marcos from his declaring martial law through his exile in Hawaii was published as Marcos: The Rise and Fall of a Regime.

In 1982 Trinidad received the Allan Saunders Award from the American Civil Liberties Union of Hawaii, and in 1999 he won the Fletcher Knebel Award from the Hawaii Community Media Council. He also received several honors in the editorial cartoon category of the Hawaii Publishers Association's annual Paʻi Awards for excellence in journalism. In 2005, the Society of Professional Journalists honored Trinidad by naming him to the Hawaii Journalism Hall of Fame.

Corky Trinidad died in Hawaii in 2009 at the age of 69 from pancreatic cancer. He was survived by his wife, Hana, and five children. His obituary in the Honolulu Star Bulletin noted Trinidad's advice for young cartoonists: take a stand.

Tita Dioso Gillespie

Tita Dioso Gillespie

Teresita “Tita” Gillespie was born in Manila, Philippines, the third of the four children of Leocadio A. Dioso, a Philippine jurist, legal adviser to President Ramon Magsaysay, and diplomat, and the former Rosario Rodriguez Fernandez. After two years at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, Gillespie moved to New York City with her parents and siblings in 1960 when her father was assigned to the Philippine Mission to the United Nations. She completed her undergraduate degree in English and philosophy in 1963 at Hunter College in New York and went on to receive a program certificate in 17th-century English studies at Exeter College at Oxford University in England and a graduate degree in Medieval French Literature and Civilization from the Sorbonne in Paris, France.

Returning to New York, Gillespie became a proofreader at Woman’s Day magazine. After marrying Mr. Gillespie, she moved to San Francisco, working as an editor at McGraw-Hill. Back in New York five years later, she continued her career as a book editor at the Free Press and John Wiley & Sons. She joined Newsweek in 1976 as an editor on the copy desk but left the magazine in 1980 to serve a two-year stint as an editor at the United Nations Industrial Development Organization in Vienna, Austria. After rejoining Newsweek, she became the magazine’s associate editor in charge of editorial style, and in 1992 was promoted to general editor and de facto copy chief. Her tenure at the newsweekly coincided with some of the most momentous historical events of the late twentieth century, including the People Power Revolution of 1986, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the eruption of Mount Pinatubo, the first Gulf War, the invention of the Internet, 9/11, and the election of Barack Obama. After retiring from Newsweek in 2008, Gillespie and her husband moved to Crisfield, Maryland.

She was a trailblazer for Asian women — and Filipino women in particular — in the field of magazine editing. In its June 2000 issue, Filipinas magazine gave Gillespie an Achievement Award for being the first Filipina to serve as Newsweek’s general editor, noting “Gillespie belongs to a short list of top-caliber Filipino journalists who have increasing influence in the international print media.” She took her role as a pioneering Filipina editor in the U.S. seriously, speaking about her experiences at seminars and mentoring several Asian American journalists.

Tita Dioso Gillespie died on December 18, 2012 after suffering several complications following a heart attack. She was 70 years old.

Sumi Haru

Sumi Haru (Source: Chicago Tribune)

Sumi Haru was born with the name Mildred Sevilla in Orange, New Jersey to Filipino immigrants but spent most of her childhood in Arvada, Colorado. She majored in Music at the University of Colorado. She changed her name to Sumi Haru when she launched her acting career because many of the roles bring offered to Asian American actors were for Japanese characters. She was a film and television actor, producer, journalist, and poet. She is best known for her appearances in Krakatoa, East of Java, MASH, The Beverly Hillbillies and Hill Street Blues.

The first Filipino American seen regularly on Los Angeles television, Haru was a producer/moderator for 17 years at KTLA on public affairs programs “The Gallery,” “70s Woman,” “80s Woman,” and “Weekend Gallery.” She produced and hosted specials on the Philippines, Taiwan, East Germany, the U.S.S.R. and Nicaragua, and was the administrative producer of the annual Toys for Tots Telethon. She hosted “Up for Air,” a weekday morning magazine program for KPFK-FM Pacifica Radio. She was co-producer and co-host of “L.A. Arts Mix,” a Cable ACE award-winning TV magazine program on the arts and culture of Los Angeles, and anchor of “L.A. News Brief” on City Channel 35.

She was a member of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) since 1974 and served multiple terms as national recording secretary and first vice president. In 1995, she became the interim president of SAG, the first and to-date only woman of color to hold the position. She addressed issues concerning the lack of opportunities and roles for Asians. She also advocated for the representation and career development of minorities in media. Haru co-founded SAG’s Ethnic Employment Opportunities Committee and helped negotiate affirmative action clauses into contracts. In 1995, she became a national vice president for AFL-CIO, the first time an Asian American served on its executive council.

She also co-founded the Association of Asian Pacific American Artists, was executive board member of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance, and co-chaired the Rainbow Coalition Commission on Fairness in the Media. Haru was a columnist for Asian Week for eight years, and her articles also appeared in The Chicago Shimpo, AsiAm, The Korea Times, Neworld, Screen Actor and Dialog. As first vice chair of the National Conference of Christian and Jews Asian Pacific American Focus Program and member of the Media Image Task Force, she initiated the publication of “Asian Pacific Americans: A Handbook on How to Cover and Portray Our Nation’s Fastest-Growing Minority Group,” published in cooperation with AAPAA and the Asian American Journalists Association.

In 1998, Haru was awarded the Visionary Award by East West Players (EWP) in recognition of her contributions to the Asian Pacific American community. Haru was honored with the SAG Ralph Morgan Award for distinguished service to SAG’s Hollywood Division in 2009. The National Women’s Political Caucus and the National Organization for Women honored Haru in its “Women of Hope” series. She also received the Most Distinguished Arts and Media Award from the UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

In 2012, she penned her autobiography, Iron Lotus: Memoirs of Sumi Sevilla Haru. “I have some of the American success indicators: a bungalow with a swimming pool, a couple of pensions, some money in the bank and a decent car,” she wrote. “Google me, and you will see that I haven’t been twiddling my thumbs all these years. To sum it up, I broke some glass ceilings. I’m sure the next generation of Pilipino Americans will push the bar a whole lot higher than I did.”

Sumi Haru, aka Mildred Sevilla, died in North Hollywood, California at the age of 75. She had been battling emphysema.

Jess T. Esteva

Jess T. Esteva with Sen. Dianne Feinstein (Photo by Cip Ayalin)

The Mabuhay Republic was a monthly newspaper that was published in 1959 by Jess Esteva. At the time, the monthly’s circulation reached 5,000 families and public officials. Esteva’s aim was “to see that Filipinos get their due.” Despite losing money on the publication, Esteva acquired a large voice for his moderate views and crusade for Filipino opportunities in America.

Born in Tigbauan, Iloilo Province in the island of Panay, Philippines, Esteva was the 12th of 13 children of a former Spanish soldier and a Filipino woman. At nine years old, he helped his father run a small store until it was ravaged by a fire. The family moved to Manila where Esteva was able to complete high school and two years of business training at San Beda College. “We were so poor,” he recalled, “that I had to go to work to care for my parents, who were then 65.” He worked with a Chinese wholesaler, going door-to-door to Manila’s bakeries selling sugar, flour, lard, and other bakery supplies.

He married Jeanette Pick, daughter of retired Col. Henry Pick in 1929, but the Great Depression left him jobless. He was an insurance underwriter and production manager during the Japanese occupation. He and his family arrived in San Francisco on August 12, 1945 only to find that Immigration had no record of his wife’s citizenship. Through the help of Congressman Franck Havenner, the Estevas, with four children were able to stay.

Esteva quickly realized that Filipinos were an unknown entity in San Francisco. In those days, the small community of Filipinos consisted of single men and former seamen. When immigration laws changed in 1965, Filipinos in San Francisco and Daly City totaled about 45,000. He established a travel agency, a remittance service, real estate investment and a finance company. “I’m still losing money (referring to his publication), but it gives me prestige in City Hall.”

When Esteva arrived in San Francisco in 1945, there was one Filipino dentist, and in 1981 there were nearly 50, about 40 physicians, a number of attorneys and 800 accountants. There were also 100 Filipino American organizations. Esteva said he was proud of the growing Filipino community and pointed out that his countrymen arrived with a good public school education, a strong desire to work and tended to stick to jobs, even menial jobs in hotels and assembly-line work.

Jess Esteva died in March 1997 at the age of 92. He had been in failing health. The Mabuhay Republic ceased operations some years ago.

ARTS

Danongan “Danny” Kalanduyan

Danongan “Danny” Kalanduyan (Source: Alliance for California Traditional Arts)

Kalanduyan was born and raised near the fishing village of Datu Piang, Maguindanao province. He had been playing his native music since he was four years old, having learned from watching his mother play. With no formal musical training, he mastered the Maguindanaon tribal style of music.

He is credited with introducing kulintang music (literally meaning golden sound moving) to the U.S. His foremost goal was to use his music to help connect contemporary Filipino American culture with ancient tribal traditions.

In 1995 he earned a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship. He was one of the most creative musicians on the kulintang instrument, which is made up of eight gongs placed horizontally in a frame and serves as the central player in a jazz-like ensemble. In 1976 he won a Rockefeller grant to be an artist-in-residence in the ethnomusicology program at the University of Washington where he earned a master’s degree. He performed at the Hollywood Bowl with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

In 2000, Kalanduyan was the Distinguished Artist-in-Residence in the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University. His two-year collaboration with the school and the Ating Tao Drum Circle, a Pilipino American student performing group, led to performances of new works based on traditional kulintang music and dance from Southern Philippines. In 2009, he was awarded a Broad Fellowship in Music with the United States Artists, ”which recognizes the most accomplished and innovative artists in the U.S., emphasizing the importance of originality across every creative discipline.”

In the last period of his life, he continued to plant new seeds, like starting an ensemble in Stockton where Filipino American farm workers protested unfair working conditions. His last performance with the Palabuniyan Kulintang Ensemble was on December 6, 2015 for the Sounds of California concert at the Oakland Museum of California.

Danny Kalanduyan died in 2016 from heart failure at the Stanford Medical Center in California. He was 69 years old.

Al Robles

Al Robles (Photo by Nancy Wong)

Alfred A. Robles grew up in the Filmore district of San Francisco with ten brothers and sisters. He was a poet and community activist. He was instrumental in the fight against the cdemolition of the International Hotel on Kearny Street where many low-income Filipino elders resided. He was one of the last people to leave the building. He founded the Manilatown Heritage Foundation to preserve the memory of the manongs and to sponsor the International Hotel Manilatown Center.

He was also a member of the Kearney Street Workshop, an Asian American writers’ collective.

His poetry and community work honored Filipino manongs (elders) but also inspired and encouraged young students, activists, writers, and artists to connect with their Filipino heritage.

Verses about traditional Filipino foods, his experiences in Hawaii, New Mexico, and community personalities in San Francisco are rendered in countless poems, and two published works: "Looking for Ifugao Mountain: Paghahanap Sa Bundok Ng Ifugao and Rappin' with Ten Thousand Carabaos in the Dark. Robles’ poetry, associated with the Beat tradition, engaged the issues of social and racial justice, which also shaped his work as an activist. He believed that organizing for social change was not enough; he turned to the creative outlet of poetry as a continuation of his physical activism.

He brought young activists and artists to Agbayani Village in Delano, a rural settlement of the Manongs, and to the WWII Japanese American internment camps at Tule Lake and Manzanar.

Children would be able to smell the rice cooking in Manilatown, a teenager could learn about their grandfather’s experience as a migrant worker, Filipinos could understand struggles faced by the Chinese. Robles wrote poems for people to read about struggles familiar to them as well as to recognize and learn from the struggles of others. He believed it was important for young activists and artists to see these places with their own eyes, to hear the stories of these places firsthand. Robles' activism was closely tied to his poetic work; in fact, his activism and poetry were one and the same.

In 2008, filmmaker Curtis Choy released a documentary about Al Robles called Manilatown is in the Heart: Time Travel with Al Robles, focusing on Robles' many personalities and community roles. It has been shown at countless film festivals, including the 2009 DisOrient Film Festival, in Eugene, OR, Asian Pacific Heritage Month 2009 in Los Altos Hills, and the 2009 Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, where it was a Finalist for the Grand Jury Award for Best Documentary.

Al Robles passed away on May 2, 2009. He was mourned at the resurrected I-Hotel, at City Lights Books in the adjacent North Beach, in Japantown, in the Fillmore, in SoMa, in all the places where he heard folks' stories and committed them to poetry.

Pacita Abad

Pacita Abad (Source: awarewomenartists.com)

Pacita Barsana Abad was born in Basco, Batanes, in the northernmost part of the Philippines. Her parents both served in the Philippine Congress, representing Batanes. She earned her BA degree in Political Science from the University of the Philippines, hoping to follow in her parents’ footsteps. She organized and joined student demonstrations in Manila against the Marcos regime. When it became dangerous, her parents sent her to Spain to continue her studies. A stop in San Francisco to visit her relatives resulted in her staying in San Francisco. She earned a master’s degree in Asian History from Lone Mountain College (now University of San Francisco). She studied painting at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. and The Art Students League in New York City where she concentrated on still life and figurative drawing.

She created over 4,500 artworks in her career – figurative socio-political works of people and primitive masks, large scale paintings of underwater scenes, tropical flowers and animal wildlife, vibrant and colorful abstract paintings – using materials from canvas to paper to bark cloth, metal, ceramics and glass. She painted the 55-meter long Alkaff Bridge in Singapore and covered it with 2,350 multicolored circles, just a few months before she died.

She also developed a technique of trapunto painting, which entailed stitching and stuffing her painted canvasses to give them a three-dimensional, sculptural effect. She incorporated into the surface of her paintings, materials such as traditional cloth, mirrors, beads, shells, plastic buttons and other objects. She said, “I always see the world through color, although my vision, perspective and paintings are constantly influenced by new ideas and changing environments. I feel like I am an ambassador of colors, always projecting a positive mood that helps make the world smile.”

She received numerous local and international awards during her artistic career, but the most memorable was being the first woman to receive the Ten Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) Award for Art in 1984, which caused a public uproar. She said, “It was long overdue that Filipina women were recognized, as the Philippines was full of outstanding women.”

Pacita Abad died of lung cancer in 2004 in Singapore. She is buried in Batanes, Philippines, next to her studio, which is called Fundacion Pacita.

Carlos Villa

Carlos Villa (Source: San Francisco Arts Institute)

Carlos Villa was born and raised in San Francisco. He spent six years in New York exploring abstract style before returning to San Francisco in 1969, embracing his lived experience and identity as a man of Filipino descent as essential to his work.

Villa was a revered mentor to hundreds of students. His paintings, mobiles, and sculptures are in the collections of Casa de las Americas, Havana, Cuba; Columbia University; the Oakland Museum of California; the Smithsonian Institution; and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Villa’s recent exhibits reflect on the life experiences of the pioneer Manong/Manang generation. Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision is the first museum retrospective of his work that was presented at the San Francisco Art Institute and the Asian Art Museum.

He is best known for his teaching, activism, and dynamic work. He grew up in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, attended the San Francisco Art Institute, where he later became a professor, and earned an M.F.A. from Mills College in Oakland, California. While he began as a Minimalist artist, Villa was committed to exploring “his own Filipino American background and spotlighting forgotten or neglected art and artists of the post–World War II era. He wanted to rebalance the canon by reviving artistic cultures that had been disrupted by colonization and war. Through teaching and curating — he organized several important exhibitions and produced multimedia projects and performances — Villa influenced many young artists. Today, he is remembered for his activism as well as his contributions to Filipino American art.”

He has received several awards, including a Pollak-Krasner Foundation grant, a National Endowment for the Arts grant, the Distinguished Alumni Award from San Francisco Art Institute, the Rockefeller Travel grant and the Adaline Kent Award.

What began as his attempt to understand his own heritage became over time an exercise in creating his own visual anthropology to represent his personal background, and the dynamics of intercultural weaving.

Carlos Villa died on March 23, 2013 in San Francisco from cancer.

MILITARY

Telesforo Trinidad

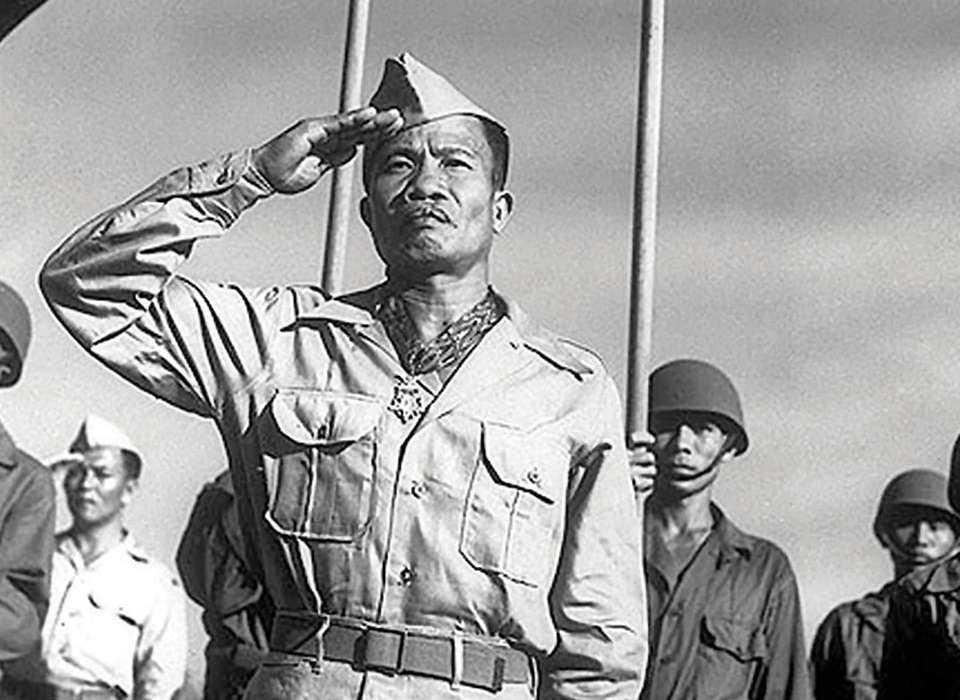

Telesforo Trinidad

Telesforo dela Cruz Trinidad came from humble beginnings and was born on November 25, 1890, in New Washington, Aklan Province, Panay, Philippines. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy as part of the Insular Force in the Philippines in 1910 and served during WWI and WWII until his retirement in 1945. Trinidad holds the distinction of being the first and only Asian American (and first Filipino) in the U.S. Navy to receive a Medal of Honor, in accordance with General Order Number 142 signed by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels on April 1, 1915.

On 21 January 1915, while steaming in the Gulf of California as part of the naval patrol established to protect U.S. interests and citizens in México, the captain of USS San Diego (Armored Cruiser No. 6) conducted a four-hour, full-speed and endurance trial to determine if the cruiser could still maintain its officially rated flank speed. At the end of the trials, an obstructed tube of one of the ship’s boilers gave way, creating an eventual chain explosion of other boilers, killing nine men and injuring several others. From the May 1915 (Vol. IX) issue of Our Navy, the Standard Magazine of the United States Navy: “At the time of the explosion, Trinidad was driven out of fireroom No. 2 by the force of the blast, but at once returned and picked up R.E. Daly, Fireman Second Class, whom he saw to be injured and proceeded to bring him out. While passing into Fireroom No. 4, Trinidad was just in time to catch the explosion in No. 3 Fireroom but without consideration for his own safety, although badly burned about the face, he passed Daly on and then assisted in rescuing another injured man from No. 3 Fireroom. “Telesforo Trinidad, fireman second class, not only received a letter of commendation but also the much-prized Medal of Honor and a gratuity of one hundred dollars.”

He lived in Imus, Cavite, Philippines until his passing on May 8, 1968, at the age of 77. He was laid to rest at Imus Public Cemetery, Cavite, Calabarzon, Philippines.

In commemoration of the 106th Anniversary of Fireman Second Class Telesforo Trinidad receiving the Medal of Honor, the USS Telesforo Trinidad Campaign (USSTTC) launched its initiative to name a U.S. Navy warship after an American national of Filipino descent who served in the U.S. Navy. If approved, Fireman Second Class Trinidad will be the first enlisted sailor and Medal of Honor recipient, and the first American of Filipino descent, to have a combat ship named after him. This distinguished honor will recognize the commitment, distinction, and valor not only of Trinidad, but also of the thousands of Filipinos who have served faithfully and loyally for the past 120 years.

Magdaleno Sanchez Duenas

Magdaleno Sanchez Duenas (Photo by Rick Rocamora)

Born in 1914 in the Philippines, Magdaleno Dueñas grew up in a convent because his parents were too poor to care for him. After finishing the sixth grade, he worked as an errand boy and later as a stevedore.

In November 1941, a month before Pearl Harbor, he joined an American-led infantry unit in the Philippines. Following the Japanese invasion and the defeat of U.S. forces in the Philippines, Dueñas was among those who fled to the mountains to become guerrilla units made up of native and American soldiers. A year later, he was captured by Japanese soldiers but he denied any knowledge of the whereabouts of any Americans. He escaped that night and returned to join the guerrilla forces in the mountains. In April 1943, Dueñas assisted in the escape of ten U.S. servicemen from the Davao Penal Colony, while the Japanese guards were asleep. The American escapees hid with the guerrillas and were eventually picked up by submarines.

After the war, Dueñas worked as a manual laborer for a mining company, as a household caretaker, and as a farmer. He dreamed of coming to America. In 1990, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Act gave Filipino World War II veterans the right to acquire U.S. citizenship. A large wave of elderly immigrants responded. In 1991, Dueñas was approached by a man who ran an immigration agency in Manila. The man promised to find housing for Filipino veterans in the United States. Instead, court records show, he crowded more than a dozen into a residence in Richmond and collected their Social Security checks. Duenas and the others said they were held, beaten and sometimes fed dog food. In 1993, a group of Filipino American community advocates discovered the situation and, in an early morning raid, helped Dueñas and nine other veterans to escape. A jury later awarded the 10 veterans $237,700 in damages against their landlord.

During his time in the Bay Area, he became an advocate for Filipino veterans. Dueñas was featured in two documentaries, Tears of Old by Joy Lacanienta, and Second Class Veterans by Don Young, about the plight of Filipino veterans who served under the command of the United States. "I haven't met a lot of people who lived so much history. It was incredible," Young said. "Even though his life had been so tough, and he was up there in age, he remembered every detail, and how many people were involved, the time and the place." Attorney Lourdes Tancinco added, "He had a life of battles. We as a community admired the way he faced his challenges. We drew energy for advocating for Filipino veterans from him."

Until his death, Dueñas waited for recognition and the promised benefits from the U.S. government for his service during World War II, activists said. Dueñas died at a convalescent home in San Francisco on February 27, 2005 from complications related to hip surgery. He was 90 years old.

Guillermo Obedoza Rumingan

Guillermo Obedoza Rumingan

World War II veteran Rumingan was born in Nueva Ecija, Philippines in 1927. During the war, he joined the guerillas. He was processed on October 31, 1945 with a USAFFE serial number Philippine Army 207231 and was honorably discharged as staff sergeant on February 20, 1946. On March 1, 1946, Rumingan enlisted as a Private with ASN PS10308671 in the Philippine Scouts, U.S. Army. He retired as a Sergeant First Class due to a permanent physical disability on March 31, 1951.

Since the 1960s, he had lobbied on Capitol Hill to fully restore U.S. government recognition and VA benefits to his Filipino and Filipino American WWII comrades. He was the service officer of the American Coalition for Filipino Veterans, Inc. (ACFV) lobby group and one of its founders. His lobbying efforts led to the passage of five bills in the U.S. Congress providing more than $300 million in benefits to veterans including full VA medical coverage and $15,000 one-time payment to each surviving US citizen Filipino World War II veteran (or $9,000 each for Filipino citizen veteran).

In 1996, Rumingan was arrested in a protest demonstration with about a dozen other veterans, when he chained himself to the White House fence to draw attention to his cause and spent a few hours in jail with fellow protester, Congressman Bob Filner.

For his untiring and humble efforts, he was recognized by three presidents. In 1999, President Clinton invited Rumingan to the bill signing ceremony of the “Special Veterans Benefit.” In 2003, President Bush asked him to witness the signing of Filipino Veterans Health bill in the Oval Office. In 2010, upon the invitation of President Obama and first lady Michele Obama, Rumingan and his fellow comrade Amadeo Urbano attended the Veterans Day breakfast in the White House.

In 2004, Rumingan was honored by the prestigious Smithsonian National Museum of American History when his story and personal photo were displayed as part of their permanent exhibit. The photo was taken when he was an 18-year-old guerrilla in World War II. It was displayed underneath the famous 1944 photograph of General Douglas MacArthur’s landing in Leyte.

In his remarks, he recalled the sacrifices and bravery of the loyal Filipino people during WWII.

Guillermo Rumingan, a disabled Philippine Scout from Arlington, Virginia, joined his fallen comrades on March 27, 2012. He was 86.

Patrick “Pat” Ganio

Patrick “Pat” Ganio (Photo by Allison Griner)

Pat Ganio was among the huge number of Filipino soldiers who were part of the American force that courageously fought Japanese troops at the Battle of Bataan. He survived brutal treatment after being captured by enemy troops after the Fall of Corregidor in May 1942. He also endured harsh interment at the O’Donnell concentration camp in Capas, Tarlac. He later joined USAFFE guerillas. He was wounded in battle and later promoted to the rank of lieutenant. He survived a near-fatal injury to become one of the most prominent activists in the fight for equity between Filipino veterans and their American counterparts. After the war, he was a major in the Philippine Army Reserves.

Patriotism motivated Ganio to enlist back in 1941, fresh out of school at age 20. At the time, the Philippines was a United States territory — spoils from its victory in the Spanish-American War — and Ganio took to serving the United States military with zeal. His father, a poor farmer, supported his decision to fight. He had always harbored high hopes for his bright young son. He distinguished himself at an early age by learning to read using papers from the local Catholic church. When it finally came time for him to start school, his father cheered him on, carrying him to class on his shoulders, hoping that his son would escape the poverty that plagued the family. Ganio would have an education, a career, a future. Ganio completed his education at the National University and the University of the Philippines with a teaching degree. After 30 years of public service, he retired from the Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology (Central Luzon Polytechnic College) as a math and science professor. He received the Outstanding Professor Award in 1980.

He emigrated to Washington, D.C. in the 1980s and started researching on the claims of Filipino WWII veterans at the National Archives and the Library of Congress. Ganio organized the Filipino War Veterans Inc. and founded the Filipino Veterans Families Foundation Inc. He was part of the decades-long lobby for U.S. recognition of the Filipino veterans’ gallant contributions to the defense of liberty and American democracy. He succeeded in pushing for the passage of a law that gave Filipino World War II veterans a path to American citizenship. He lobbied successfully for other benefits like health care, disability assistance and burial rights.

In August 1997, more than 100 protesters marched on the White House in Washington, D.C., demonstrating against U.S. treatment of Filipino World War II veterans. The frail elderly veterans, chained themselves in protest to the White House fence and staged a “die-in.” Calling the protest the Second DeathM, in reference to the first Bataan Death March, 15 of the veterans “died” in front of the White House. They were arrested by the Secret Service, fined, and released from custody. Ganio was one of them.

Ganio, a Purple Heart recipient, said this at an address to the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee hearings: “It is comforting to feel that America cares for those who bore the battle. But as we think of the supreme sacrifices we paid for serving under the American flag, it is shocking and painful to think that in our low moments to feel betrayed from a friend we trust.”

“Pat’s life was truly amazing. He had a loving family and a successful teaching career after surviving as a WWII POW after the battles of Bataan and Corregidor,” said veterans advocate Eric Lachica. “We who knew this kind, humble and inspiring hero, were truly blessed.”

Pat Ganio died on June 15, 2019 at his home in Jacksonville, Florida at the age of 98.

Jose Cabalfin Calugas

Jose Cabalfin Calugas

Born in Barangay Tagsing, Leon, Iloilo in the Philippines, Jose Cabalfin Calugas was the oldest of three children. He lost his mother at 12 years old. He joined the Philippine Scouts at the age of 23, and went to Camp Sill, Oklahoma where he went through basic and artillery training. After completion, he was assigned to 24th Artillery Regiment of the Philippine Scouts and posted at Fort Stotsenburg, Pampanga in the Philippines. While there he married and began to raise a family.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl harbor on December 8, 1941, Calugas was a mess sergeant with Battery B of the 88th and sent with his unit to the Bataan Peninsula. His battery and regiment were attacked on January 1942, taking on the brunt of the Japanese assault. Calugas’ heroics in 1942 is described as: “The action for which the award was made took place near Culis, Bataan Province, Philippine Islands, on 16 January 1942. A battery gun position was bombed and shelled by the enemy until one gun was put out of commission and all the cannoneers were killed or wounded. Sgt. Calugas, a mess sergeant of another battery, voluntarily and without orders ran 1,000 yards across the shell-swept area to the gun position. There he organized a volunteer squad which placed the gun back in commission and fired effectively against the enemy, although the position remained under constant and heavy Japanese artillery fire.”

Calugas was the first Filipino American Medal of Honor Recipient of World War II, an award he did not get until the liberation of the Philippines in 1945.

He survived the infamous Bataan Death March. He spent nearly eight months at Camp O’Donnell where his malnourished body was frequently beaten. When he was released to work on a rice mill in 1943, he secretly joined a guerilla unit.

After the war, Calugas was assigned to the 44th Infantry Regiment on Okinawa. Japan and after fulfilling the requirements, he was granted U.S. citizenship. He retired from the U.S. Army in 1957 with the rank of captain. In 1961, he earned a degree in Business Administration from the University of Puget Sound and worked for the Boeing Corporation. He also got involved in several veterans groups within the Seattle and Tacoma area.

Jose Calugas died on January 18, 1998 at the age of 90 in his home in Tacoma, Washington. His Medal is held at the Museum in Fort Sill and on a relief at Mt. Samat, the national memorial to the Filipino service and sacrifice of the WWII years. Within the family housing area in Fort Sam Houston, Texas, a street known as Calugas Circle was dedicated in this honor in 1999. In 2006, a 36-unit apartment building for low-income and disabled residents was dedicated as the “Sgt. Jose Calugas, Sr. Apartments” in High Point, Seattle. On Memorial Day 2009, his memory was honored at the Living War Memorial Park.

Source: Google and Wikipedia