We Call Her Mahal

/First published in Lifestyle Asia, September 2016

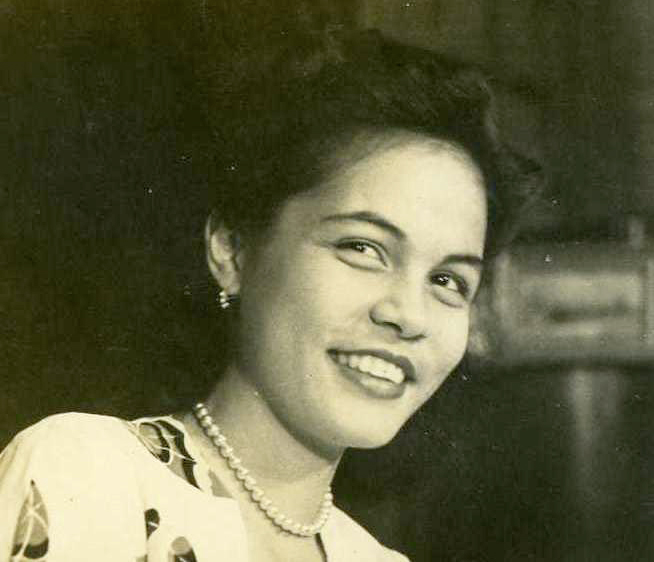

Young Armida Siguion-Reyna (Photo courtesy of the Siguion-Reyna family)

There’s the one about the first time she met the half-brother whom their father Alfonso brought to the family house in Maysilo, in Malabon, one afternoon soon after the war. With one look, she knew that Juanito Furagganan was her brother. His mouth, nose, cheekbones, and the way he carried himself marked him as a Ponce Enrile. What struck her most was that the love child was born on Valentine’s Day. Authentic.

There was another where, weeks before the wedding to fiancé Leonardo, her mother, Purita, asked the groom-to-be if he would still allow Armida to perform. He answered, “Operas and concerts are fine, but not shows at the Manila Grand Opera House with the likes of Pugo [a comedian].” Her daughter raised an eyebrow and wordlessly returned the engagement ring. The next day, my future lolo apologized, accompanied by his rosary-praying tiyahins (aunts). The almost runaway bride took him back, but not until after she had laid out her expectations of married life. Authentic.

Leonardo Siguion-Reyna and Armida Ponce-Enrile on their wedding day, November 1951. (Photo courtesy of the Siguion-Reyna family)

And the one where, while on the set of a Viva Films’ project, she asked why the heavy breakfast spread of a whole loaf of bread, platters of cocktail hotdogs and fried eggs, butter and cheese was being laid out for her character’s solo meal. “Tita Midz, (the name she was called)” the production designer explained, “Mayaman ka rito, ito ang breakfast mo. [You’re rich in the film, this is your breakfast.]” And she riposted, “Mayaman ako sa tunay na buhay, ang breakfast ko, kape.[I’m rich in real life but my breakfast is just coffee.]” Authentic.

As kids, my brother Rafa and I would sleep over at our grandparents’. One Sunday, they took us to Bulacan, where among other things, we visited a pastillas factory, ate steamed corn on the cob bought from a road vendor, and checked out the Angat River dam. At one point, a less than wonderful stench filled the van. Mahal looked at us and asked, “Who did that?” Lolo mischievously pointed at me. I replied with a version of Eenie Meenie Miney Moe, to chance on the culprit. My finger landed on Mahal. She insisted my grandfather repeat the procedure, and when he did, his finger still landed on her. She kept on shrieking and yelling, “Not me, no way!” The memory still makes me smile. Oh, yes. Authentic.

Never A Reyna Elena

Armida Purificacion Candelaria Liwanag Ponce was born in Malate, Manila, to Alfonso, in 1936--who was made name partner of DeWitt, Perkins and Ponce-Enrile--and Purita Liwanag, a music teacher and alumnus of the UP Conservatory of Music.

Mahal would describe her childhood with tales of carefree abandon, running around the fields of Maysilo, befriending children her age, attempting to string sampaguita blossoms into garlands, and eating freshly picked produce like cucumbers and tomatoes straight off the vine. The latter is a memory she often told me, because I hated tomatoes. She admitted to being quite naughty as a child. She spent a chunk of her younger years shuttling between her parents’ residence in Maysilo and their Liwanag grandparents’ in Pinaglabanan, San Juan, where the favorite was Raquel, the oldest daughter. One Christmas Eve, in a fit of rebellion (and boredom), Mahal used a razor on their driver’s uniform, cut it into strips, and she ended up being put into a sack and hung from a house beam. It was standard punishment for the young during her time.

“Once, in Disney World, she declared she couldn’t finish her meal and gave it to me. A few minutes later, she looked at me, askance. “Terible, ang lakas mong kumain! [Terrible, you eat so much!]””

That sorry episode brought her back to Maysilo, where she snuck into her mother’s boudoir and stumbled into her diaries, the reading of which made Mahal declare to herself she would never love a man more than he loved her. This piece of advice was something she would often tell all her granddaughters, with Lolo harrumphing and making faces in the background.

The Santacruzan in Maysilo was canceled during the war years, so Mahal never got to be Reyna Elena. Years later, I was chosen as one of the Flores de Mayo in Laguna. Mahal was so happy for me. She not only supplied the cloth and had my terno made by Patis Tesoro, she also watched me walk down the streets of Pagsanjan.

First Attempts at a Life in the Spotlight

In June of 1946, Fernando Poe’s Royal Palaris Productions shot a film in Maysilo. Director Mike Caguin gave Mahal a screen test in the studios in San Francisco del Monte in Quezon City, a property the first Fernando Poe left to his son Ronnie, and which Mahal would often visit years and years later.

Mahal passed the screen test and was told that Fernando Poe wanted to get her as juvenile lead for his next film, but becoming an actress this early in her life wasn’t to be. Her father wanted her to finish her secondary education in the US, and so off she went to the Academy of St. Joseph in Brentwood, Long Island.

A year before she graduated from high school, Mahal heard on the radio about auditions for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “The King and I.” She tried out with “The Italian Street Song” as her audition piece. She got a call back for a second audition and told everyone in St. Joseph’s about it. This upset the nuns in the faculty who threatened to expel her. Soon enough Lolo Alfonso was on the phone, telling Mahal to obey her teachers. Mahal couldn’t help but think again of the movie offer her lawyer-father forbade her to accept.

The Orphan Lawyer Who Loved Her

When my grandfather Leonardo started courting her, many members in the family scratched their heads. He was a brilliant young lawyer in Lolo Alfonso’s law office, albeit without a cent to his name. When he proposed and she said yes, Lolo Alfonso yelled, “Armida, if you marry that man you will ride a kalesa (horse-drawn cart) for the rest of your life!” He had already cut down what could have been an early acting career in films, and stopped her from going further into Broadway. So, she married the orphan from Pangasinan.

Theirs was a fruitful and happy marriage, although some outsiders assumed Mahal called the shots. Lolo was so secure about what he had done and had achieved on his own, he remained unaffected by public perception. He made Mahal happy, supporting her in all her endeavors, from helping her spread Filipino culture by financing her “Aawitan Kita” television show and all the movies she produced, to backing her up in her many fights against the early Movie and Television Review and Classification Boards (MTRCB). He offered legal advice when Joseph Estrada appointed her as chair of the MTRCB in 1998, and supported her run for Congress in 2001. Support for his wife extended to bemusedly watching her try on 18 pairs of shoes in a store in Rhode Island and buying every single one of them.

Speaking at a press conference as MTRCB chairperson. (Photo courtesy of the Siguion-Reyna family)

Memories from several vacations bring back images of Mahal, who cheerfully took on the role of cook in the family apartment in New York and didn’t raise a fuss except when someone dripped water on the kitchen floor, spilled salt on the dining table, or failed to properly put toilet paper in place in the bathroom.

As my father noted in his eulogy at Lolo’s necrological services in December 22, 2010, Lolo “disdained emotional display. How ironic that he married an emotional woman. How logical for them to beget three proudly and happily schizophrenic children.”

The couple in their twilight years, 2008. (Photo courtesy of the Siguion-Reyna family)

An Industry Stalwart-Dragon Queen

Mahal will always be remembered, for “Aawitan Kita.” Even today, in places as varied as check-in lines at the airport, at the hairdresser’s, or when I’m buying something and they see my name printed on the receipt, I am always asked “Kaanu-ano mo si Armida? [Are you related to Armida]” When I confirm my relation to her, I’m invariably told how much she was a part of people’s childhoods, of how their grandparents and parents loved watching the show, leaving them no choice but to watch and appreciate it as well. For Mahal, “Aawitan Kita” was all about expressing what it is like to be Filipino through song.

Armida's grandchildren appeared with her in an Aawitan Kita Christmas special. (Photo courtesy of the Siguion-Reyna family)

Likewise, for the films she produced, among them Hihintayin Kita sa Langit, Ikaw Pa Lang ang Minahal, Saan Ka Man Naroroon, Abot-Kamay ang Pangarap, Inagaw Mo ang Lahat sa Akin, Ligaya ang Itawag Mo sa Akin, Ang Lalaki sa Buhay ni Selya, and Azucena. As a producer, she took great pride in wrapping up her projects on budget, and on schedule. She did not allow her actors to “lagare” — the industry term for shuttling from one movie set to another; when she signed you up, you were hers for 21 shooting days within 35 calendar days. She put a stop to the practice of film crew sleeping in film equipment trucks on location shootings, and put them up where she and the actors were billeted. She didn’t give my papa perks because he was the producer’s son; on the contrary, with him she was stricter, giving him a budget of x number of rolls of film negatives to use and when he’d go past that, she’d deduct the cost of film and cost of development from his talent fee.

Finally, for her anti-censorship stance and pro-freedom of speech position in the film industry, sparring with people who didn’t share her views and who wished to impose their moralist standards on the movie-going public, she made enemies. She dubbed her detractors as “Jurassic” censors. They in turn called her names. She didn’t mind and trudged forward.

As MTRCB Chairman, she made sure that the people on her MTRCB board were pro-industry, and intelligent in film and television classification, rather than being moralists first. In my mostly Catholic elementary school, my classmates would tell me they’d see her name in media, oftentimes attached to a not-so-tasteful moniker given by her enemies, the kindest being “the fire-breathing Dragon Queen.” When I told Mahal about all these, she told Rafa and I that someday, we’d appreciate all the fighting she had done for the film arts.

Mahal to Her Grandchildren

If she was a fire-breathing Dragon Queen to everyone else, she was a great grandmother to us. My brother and cousins and I are such opinionated people — to the chagrin of our parents — because we got it from Mahal.

We loved Sunday lunches at my grandparents’ home. Our first go-to place was always the cabinet of sweets that Mahal stocked for us weekly, with Kisses, Crunch Bars, Maltesers and Pringles. We’d be brought to the Escolta at the Manila Peninsula and treated at the gift shop, with candies, or the latest Betty and Veronica Digest. One time, I asked for a ladies’ hat, a cornflower-blue number in piña fabric, with flowers on the brim. I had no use for such a hat except in my dress-up games, but Mahal was amused anyway; she bought it for me. Years later, when I popped into the shop, the sales associate who attended to us shared that she hadn’t forgotten watching Mahal put the hat on me. I haven’t forgotten it either.

The author and her grandmother Armida (aka Mahal) in New York, 2010. (Photo courtesy of the Siguion-Reyna family)

She could be particularly testy with us, especially her granddaughters. She fed us sweets as children, but soon as we hit our teens she’d make biting comments about our eating habits. Once, in Disney World, she declared she couldn’t finish her meal and gave it to me. A few minutes later, she looked at me, askance. “Terible, ang lakas mong kumain! [Terrible, you eat so much!]”

Mahal had high, exacting standards, but she never considered anyone beneath her. She could scold a member of the household help, and how. But she also dressed down whoever crossed her path, if they happened to displease her, even if they were supposedly her equal. She was not a snob.

In the Twilight

Mahal doesn’t talk much these days, but her eyes are still always shining, and once in awhile she’ll blurt out how beautiful she looks, or how good-looking she thinks her grandchildren are. She can barely finish a sentence; the other night at family dinner, visiting pianist Rene Dalandan played “Aawitan Kita,” and she went teary-eyed.

In my mind, she remains a girl in Maysilo, a young lady who tried auditioning for Broadway, a beloved, headstrong wife, a fire-breathing dragon queen, a woman who espoused Filipino culture above everything else, a mother, and grandmother.

She is Mahal. Authentic.

Sara Siguion-Reyna is Assistant Editor of Lifestyle Asia.