Tony Remington’s Launching Point to Fil-Am Consciousness

/Leland Wong and Tony Remington at Tony's opening (Photo by Leon Sun © 2017)

Tony attended the working-class and well-integrated Sacred Heart Grammar School on Fillmore and Fell streets. In conversations and email exchanges we’ve had over the years, Tony has vividly recalled Motown music, then in its prime, along with fond memories of the classic songs, soul dancing, and a growing consciousness of race that, in general, was positive.

It was not until moving to Daly City when he was 13 that this awareness developed into feelings of isolation and a growing self-consciousness. “I chose to become a photographer in 1970. It was not until 1971 to 1974 at San Francisco State College that I began a more direct line of questioning, which is now clear within the current landscape of Trump.”

My Selfie (Photo by Tony Remington © 2017)

Asked about, and then later criticized for his complete focus on Filipinos in his work, Tony’s own self-doubt, coupled with a continued study of history and current events led him to conclude that it was “to balance against Western bias.” However, as Tony puts it “I always maintain that my work is not an attempt at professionalism but simply a personal experience as a Fil-Am. As a fine art photographer my dedication is to photographic purism, the ambiguity of what that might mean, and the genre of personal documentary. I've never considered myself an activist, but I've often been called one. I try not to think about it. I just enjoy the process of creating work.”

Growing up in San Francisco gives Tony the unique perspective and experience that includes “watching Willie Mays make shoestring catches and homer over Candlestick’s centerfield wall, playing in bands, the ‘60s, participating in the art underground, the punk era, the Mission, the Castro and working with Al Robles in the post-Manilatown era.” This period of time was after the brutal eviction at 3 a.m. on August 4, 1977 and subsequent demolition two years later that turned the International Hotel into a pile of bricks on palettes being shipped to contractors across the Bay.

“I look back now and wonder if were they truly great times? Or, was I just young? A bit of both I think.” Tony has always considered that working with Al Robles and Presco Tabios in post-Manilatown was the “greatest, happiest and fulfilling of times. For me, that was the first time I fit in. I wore my camera religiously and knew I was making images that would live on their own merit, in spite of me, and my failures. They were the children I never had.”

Although he traveled to the Philippines with his parents on several balikbayan trips, extensive visits did not begin until 2006. His experience working in post-Manilatown was simply part of a larger growing awareness of the “unfulfilled pieces of the puzzle of Fil-Am identity.” At some point, for Tony it was important “to return to the source, to understand after the death of my parents, their love for the Philippines. From 2005 to 2016 I lived in the Philippines. Mostly, I was in San Nicolas, Pasig. Kapasigan, malapit sa municipio. I learned enough Tagalog to get around Metro-Manila on public transportation and I was the official photographer for one season of the Philippine Basketball League, the PBL.”

Ondoy Flood. Pasig (Photo by Tony Remington © 2009)

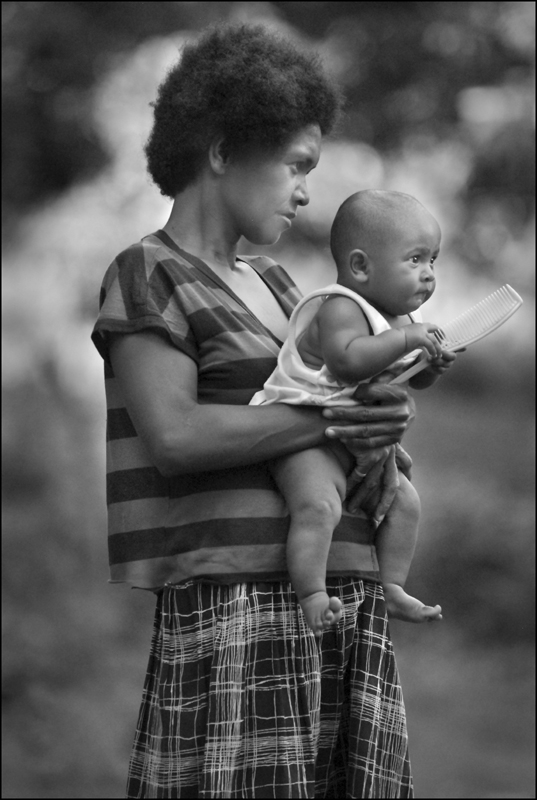

Aetas, Mother and Child. Marong Bataan (Photo by Tony Remington © 2010)

Shelter. Avenida, Manila (Photo by Tony Remington © 2012)

When I asked what the most important thing he learned from these travels was, his response was “to completely lose any sense of inferiority, misplaced attempts to fit in, or doubts of personal identity. I gained a reinforced and empowered sense of what my true American identity is as a Fil-Am Asian American. What I miss most about the Philippines is the rainy season, the sound of sudden pounding sheets of rain and the stillness in its aftermath. So again, for me Manilatown in San Francisco was really the beginning of the discovery of many Manilatowns on many different levels.”

From 1977 to 1981, Tony Remington worked with poet, visionary, community activist, Fillmore/Manilatown pianist and hipster and close friend of the manongs, Al Robles. Tony’s iconic image of Al Robles is “of him standing and staring. While the first basement manifestation of post-Manilatown was under construction, Al suddenly became silent, stopped and stared. I don't think anyone else caught it except me, But I photographed him. I could tell he was dreaming Manilatown back into existence, that his will would have its way. What's interesting and why I find this so iconic, is that years later after many of his favorite manongs had passed away, the final post-Manilatown basement senior center was closing. Completely by chance I happened upon him standing alone in the basement. Standing in the exact same way that I had caught him years earlier, staring at the blank walls, I swear I could hear manongs singing and dancing in his mind’s eye on those blank walls, and that Manilatown would just rise again in the ether of dreams that Al had willed into existence. It was a spiritual and dramatic moment, in the dusk, with Al standing there staring. An orange neon light leaked in from across the street, splashing on the blank wall before him. I saw this as the law of dharma, a duality, a reverent moment.”

AL Standing, in the blank walls of your dreams (Painting by Tony Remington © 2017)

Tony Remington’s very recent paintings and photographs taken in the Philippines during the ten-year period when he lived there are currently on exhibit at the International Hotel Manilatown Center on Kearny Street in San Francisco. In a recent discussion, we talked about several of his paintings and eventually we focused on three outstanding pieces that are among the most evocative. They completely capture the individual subject’s essence as well as the deep and uniquely historical flavor of the Kearny Street neighborhood and that particular era.

Benny Gallo lived at the San Joaquin Hotel on Columbus Avenue near Kearny and Jackson. In describing Benny, Tony recalled, “He made three altars, one from an empty suitcase half, one from a flat chunk of styrofoam, and the most ambitious one, from three chunks of styrofoam packing stacked like a tabernacle that he called Wondering Sight. It was adorned with flowers lined with red paper and had crosses made of medical tape. It was crowned with a picture of a woman. When I visited him he would say, ‘The little people were here again last night dancing around his Wondering Sight.’ I thought of Benny as an art visionary and also as a link to Island mysticism. His other piece was an empty suitcase lined with aluminum foil and hung on the wall, and inside it was a simple, small elongated glass vase holding a red rose or two. He named it King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. His final piece, a flatter piece of styrofoam packing covered with aluminum foil, was called The Fighting Lady. I visited him one day and he said of his Fighting Lady, ‘I don't know why, but she's crying!’ He then repeated ‘I asked, why are you crying?’ Turning to me, he exclaimed, ‘I don't know why she's crying!’"

Benny Gallo (Painting by Tony Remington © 2017)

José Ferrar came to Manilatown after raising cockfighting roosters in Blythe, California. A great mandolin player, he had been a musician on the ocean liners that crossed the Pacific. Tony Remington had the opportunity to observe and occasionally play guitar and “jam” with the neighborhood musicians at the post-Manilatown Senior Center basement. In his opinion José Ferrar was the best among them, describing his chord selections as being colorful and precisely harmonic.

José Ferrar (Painting by Tony Remington © 2017)

From January 27 until July 31, the seemingly inexhaustible and divinely inspired Tony Remington created painting after painting. He was reminded of those times back in the days of old Manilatown, and was surprised and moved at how well the spirit of the manongs transferred from his photographs so seamlessly to the paint. “It was not haunting, but a reunion each day occurred as I saw the images reborn on canvases close at hand. I am now seeing the importance of writing, as I'm beginning to forget things. Most important to me is the struggle for justice, to question the depths of our spiritual values that at this time appear quite shallow in the faint shadows of hubris and false self-righteousness. It's my simple hope that I've created images of historical value and simple understanding.”

When asked where he got the title for his art exhibit, Tony responded: “In my conversation with Caroline Cabading (E.D. of Manilatown Heritage Foundation) she pointed out that “the arrival of the 1920s Manong Generation was the launching point from which Filipino Americans were able to soar in this country. Everything that we have accomplished we owe to this first major immigration wave.”

These days, at the Manilatown Center you just might see Tony looking around; much like Al did in the old Manilatown, viewing the landscape of dreams and hearing ancient stories and distant music. Often, he is holding two or three canvases under his arms, his hands grasping freshly minted images from his soul. In talking about the exhibit itself, Tony shares his artist’s statement: “With humility I exhibit my work, as there are many more deserving. My only pretense is to dissolve into the anonymity of an evolving collective consciousness. That would be enough, from launching point -- an abundance of new beginnings for us all.”

The spirit of the manongs is there in the streets and alleys of what used to be a thriving Filipino American enclave, Manilatown, or simply “Kearny Street.” That spirit is there in the community and in all of the gatherings at the I-Hotel Manilatown Center. The different photographs, exhibits and memorabilia there are filled with that spirit. And that spirit is certainly in the heart and in the art of Tony Remington. His work is not about him. It is him. It has become the launching point of his own spirit and his own legacy. Mabuhay ka Tony Remington!

Tony Remington's exhibit at the I-Hotel Manilatown Center runs until August 31, 2017

Carlos Zialcita was born in Manila and grew up in San Francisco after migrating to the United States as a child in 1958. He is a jazz and blues harmonica player, singer, songwriter, bandleader, recording artist, writer, and educator. He is the Co-Founder, Producer, and Executive Director of the San Francisco Filipino American Jazz Festival, and a Board Member of the Manilatown Heritage Foundation in San Francisco. Photo by Tony Remington ©2008

More articles from Carlos Zialcita