Tips for Writers: Copyright and Publishing Rights

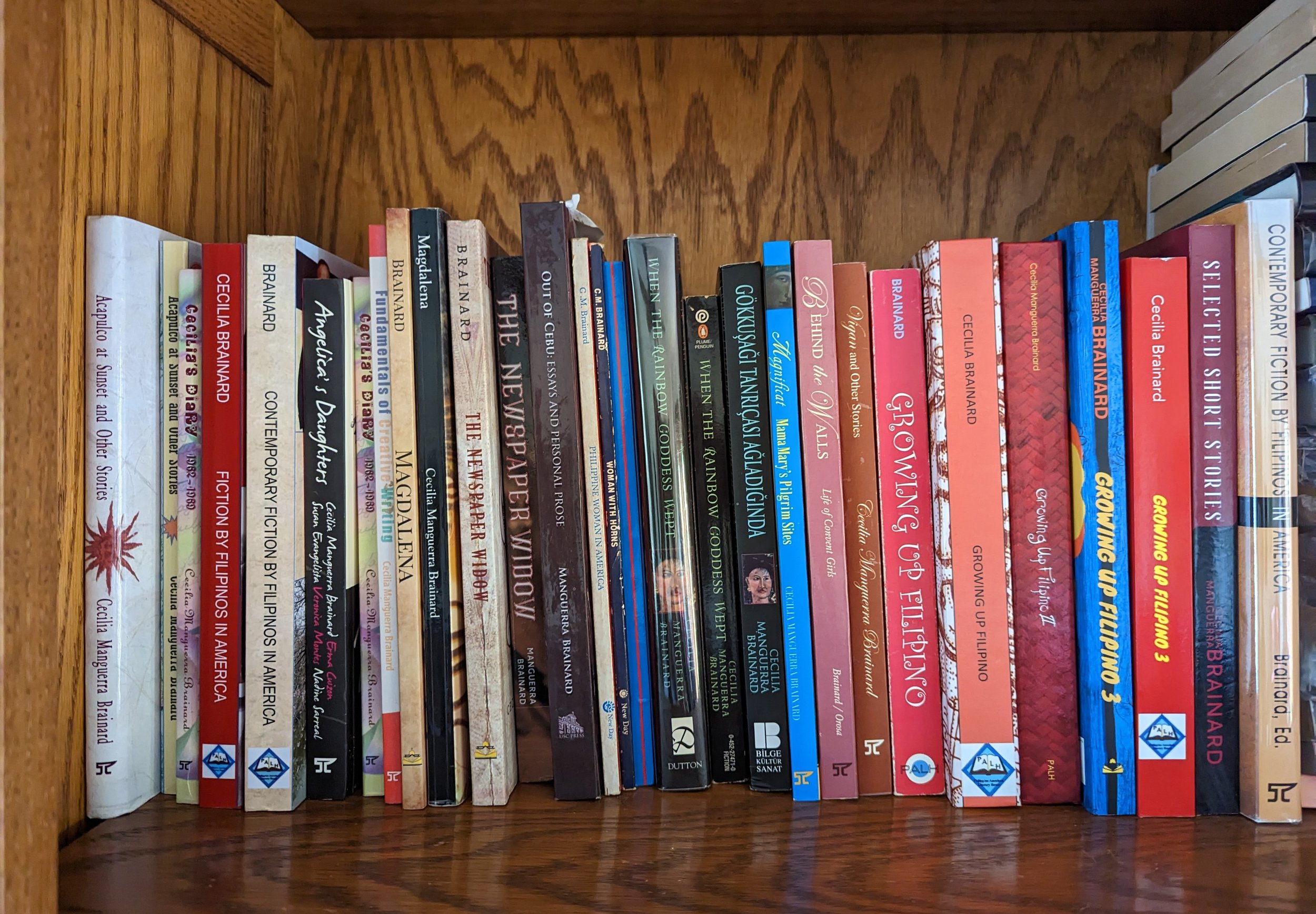

/(Photo by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard)

These tips can help writers who have completed their books and are looking for, or have found, a publisher for their work. They need to understand what copyright is and what rights are inherent in their work as they negotiate a contract or agreement with the publisher.

Note that I say “negotiate,” which means a writer should not automatically accept the contract sent by the publisher to them; the writer is entitled to negotiate certain rights with the publisher. In other words, the author has the right to rewrite the contract draft and send this back to the publisher. This can be a back-and-forth process until both author and publisher are satisfied with the contract.

First of all, let us define “copyright.”

According to Copyright.gov, “a copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work.”

Another definition given by WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization): “Copyright (or author’s right) is a legal term used to describe the rights that creators have over their literary and artistic works. Works covered by copyright range from books, music, paintings, sculpture, and films, to computer programs, databases, advertisements, maps, and technical drawings.”

Put simply: Copyright is the legal right of the owner of intellectual property.

Since 1976, when a writer completes a book, he/she automatically owns the copyright to that work. Registration of the work in the Copyright Office is voluntary but is necessary if one has to bring a lawsuit for infringement.

In the Philippines, there is a Copyright Registration office at the National Library. In the US, there is a Copyright Office, a government office, in D.C. The US and the Philippines are members of the Berne Copyright Convention and as such are provided at least the minimum protection set out in the Berne Convention (https://www.copyrightlaws.com/introduction-international-copyright-law/)/.

(Photo by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard)

Own The Copyright

After a writer completes his/her work and before he/she starts submitting this to publishers or agents, I suggest registering the work for copyright. As mentioned, this will give the writer legal protection if the work should be pirated or plagiarized.

Second, when the writer finds a publisher, the writer should make sure the work is copyrighted in the writer’s name only and not with the publisher. There are many Philippine publishers that are copyrighting books in both the names of the authors and publishers. This is not good practice. If the book or work is copyrighted in both the author’s and publisher’s names, this suggests the work is now co-owned by both the author and publisher.

I’ve heard from a director of a university press in the Philippines that this is not what joint copyright annotation means. She said the work still belongs to the writer, and it is the book that is copyrighted in both the publisher’s and author’s names.

I disagree with this director because right there on the copyright page, the annotation will state that the copyright is in both the publisher’s and author’s names; anywhere in the world this means the work is co-owned by both publisher and author. The result is that the author will now need to seek permission from the publisher if the author wants to negotiate other rights of the work, such as movie, serial, translation or digital rights.

This annotation of joint copyright names of the author and publisher can pose complications to the writer or his/her heirs. Let me cite some real instances where difficulties have arisen.

Two families approached me as publisher of PALH to reprint the books written by their fathers. The books were specifically about the World War II experiences of the fathers. The books were first published over 30 years ago and have been out–of-print for decades. However, because both books note the copyright in the names of the fathers and the publishers, ownership of the books are murky. Both families have had to go back to the publishers to ask for rights reversal in favor of the families. Unfortunately, in both cases, the current managers of the publishing houses have not agreed to revert the rights, thus blocking the families from reprinting the books.

If the fathers had known better and copyrighted the books in just their names; the copyright ownership would be clear. However aside from copyright registration and annotation, the contract between the author and publisher should define what rights the author has assigned to the publisher, and there must be a termination clause stating that if the work is out-of-print or no longer sold, all assigned rights revert to the authors.

These two points are, therefore, important: ensuring that the copyright is in the name of the author; and that the agreement assigns specific rights and has a termination clause or rights reversal clause.

“When the writer finds a publisher, the writer should make sure the work is copyrighted in the writer’s name only and not with the publisher.”

Assignment of Rights

This leads me into the topic of “Assignment of Rights.”

First of all, “publishing rights” are not the same as “copyright”. The copyright belongs to the original creator of the book. The publishing rights are assigned to others by the copyright owner, allowing them to reproduce the work.

According to lawinsider.com, publishing rights means the “production, manufacture or other exploitation, by means of text, still photo and /or still illustration in any format now known or hereafter developed (including, without limitation, books, magazines and newsletters and customary subsidiary rights such as paperback reprints, book club publications, audio recordings, etc).”

Writers should understand that they own all rights to their work. Sometimes authors do not even know all the rights they own, such as movie rights, television rights, anthology rights, translation rights, serial rights, book club rights and so on; but regardless, they own these rights, and should therefore be careful about what rights they assign or give to publishers. They should limit the rights that they assign to publishers and hang on to as many rights as they can. By this I mean, a writer should not assign “all rights” to a publisher, for instance; doing so means the publisher can have a movie made of the work and the writer would not be entitled to a cut from that venture.

When the writer is reviewing the publisher’s contract, the writer should pay attention to what rights he/she assigns to the publisher. This is usually found in the first part of the contract. I myself assign only Philippine publishing rights to my Philippine publishers, thus allowing me freedom to get my work published in other parts of the world. I do not assign digital rights to my Philippine publishers, because I take care of that myself. Writers should be careful about giving up digital rights to their work, because sometimes publishers will tag that in their contract without clarification to the writers.

The contract will have a section about copyright, and here is where I recommend that writers remain firm that the copyright of the work should be owned by the author only. If you allow the name of the publisher included in this clause, you may have just given them half-ownership to your work.

The contract will include other items, which the writer should read carefully: royalties, free copies, promotion, subsidiary rights, etc.

A really important clause that is sometimes not included by publishers is the termination clause. My early contracts from my first publisher did not have a termination clause, but fortunately at some point in time, since the publisher did not pay me royalties, I negotiated reversal of rights for all my books, and I forgave the publisher for their non-payment.

What termination clause refers to is the contract providing an end to the contract under certain conditions. For instance, if book is no longer in print or available for sale, all rights revert to the author. This means that the author or his/her heirs can have the freedom, without having to get a rights reversal document from the publisher, to get the book reprinted. This can be a big help to the heirs of the authors who will have the freedom to reprint the book years after the original publication.

In my book contracts, and at the advice of my lawyer, I add what is known as a “sunset clause.” The clause states something like, “All rights assigned to the Publisher under this Agreement shall fully revert to the Author or her Heirs 25 years after execution of the Agreement unless otherwise agreed upon by both parties.”

I have enjoyed the fruits of this sunset clause in my early books. Amazingly 25 years have passed, and I find that my books still have a market, but the original publishers are no longer actively selling the book. Without needing to get a rights reversal document from the publishers, I have been able to go ahead and get the books reprinted.

This sunset clause will give writers’ heirs the freedom to get their ancestors’ works reprinted without having to hunt down publishers for a rights reversal document.

These are some tips I have for writers. I am sure there are more important information on copyright and publishing rights, so I do advise you to read up on these topics further.

Sources:

US Copyright Office - https://www.copyright.gov/

Philippine Copyright Registration, National Library of the Philippines - http://web.nlp.gov.ph/nlp/?q=node/646

Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works - https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard is the award-winning author and editor of over 20 books, including the novels: When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, Magdalena, and The Newspaper Widow. Her recent book is Growing Up Filipino 3: New Stories for Young Adults, which she edited and collected. Cecilia also runs the small press PALH (Philippine American Literary House) which has published books by Linda Ty-Casper, Veronica, Montes, as well as anthologies about Filipino American and Asian American topics. Cecilia’s official website is ceciliabrainard.com.

More articles from Cecilia Manguerra Brainard