This is American History

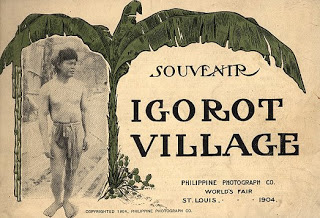

/Image of pamphlet from 1904 World’s Fair Exhibition, St. Louis. (Source: the Jonathan Best and John Silva Collection)

An Education

In this small California town in the ‘90s, Mr J. taught my high school history classes. I remember perusing my World History syllabus, noting the absence of Asia, Africa, South, Central America; so, one day, I raised my hand:

“Mr. J, if we took European History last year, why is this class also focused on Europe? Are we gonna talk about other parts of the world?”

“The list of what I did not learn goes on, from the horrific to the celebratory, from the impact of U.S. policies abroad, to the contributions of Filipinos locally. ”

He quickly replied: “If it wasn’t for Western Europe, we wouldn’t have civilization or democracy. So we’ll study other parts of the world only in relationship to Europe.” Case closed. He might as well have hammered his gavel to declare his jurisdiction.

It was as though someone had drawn the air out of me. I didn’t have the language or the politics to retort. But the lesson had been learned.

Over time, I followed a similar conclusion: We do not include Filipino American History in American History. This is what the textbooks told me. No books mentioned that Filipinos landed in California in 1587; created settlements in Louisiana after escaping Spanish Galleons in 1763; fought the United States for independence in the Philippine-American War in 1899-1913.

They did not mention how the U.S. put Filipinos on display at a human zoo in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904; called Filipinos dogs and niggers; kept military bases in the Philippines for over 100 years, leaving the legacy of prostitution, toxic waste and fatherless “Amerasian” children. Of course these facts were not taught: Why would Americans want to take responsibility for all this?

Souvenir Igorot Village. St. Louis: Philippine Photograph Co., 1904 (Source: University of Delaware Library)

My education, too, effaced Filipino American resistance: the farmworkers of Delano, co-creators of the United Farmworker’s Movement; those (like my grandfather) who served the U.S. Military and fought for recognition; the organizers at the International Hotel; the nurses, hotel workers, airport workers, activists and artists. The list of what I did not learn goes on, from the horrific to the celebratory, from the impact of U.S. policies abroad, to the contributions of Filipinos locally. That I only began to learn these things in my twenties showed that Mr. J’s conclusion rippled far beyond that day in the ‘90s as I sat, silenced.

That moment was a turning point: In college, I was determined to recollect what I had been deprived of in school and by parents who feared that passing down our language and culture would subject me to discrimination. I wanted to turn the tide, to speak up against every Mr. J, whose judgment on my place in the world had actually set things in motion.

A Re-Education

Often, I revisit that high school moment, calling out to Mr. J and to the world, “These stories are important! Listen!” These days, when I am invited to speak about my poetry and its themes, people say, “It’s great — that you’re proud of your history.” Sometimes: “I know Filipinos who are (nurses, airport workers, mailmen) – such sweet people,” thinking that they are validating my story. But I want to scream, “This is not only my history, this is your history too!”

In my poems, I describe a child alienated from her own culture, living in small towns throughout the country; a solitary Filipina lost in All-America, preferring county fairs and cowboy hats to lumpia and adobo. While some presume that, being of this lineage, I grew up consuming troughs of pancit and attending fiestas, my poems describe tumbleweeds, microwaved dinners and apple pie. My life was an experiment of the Melting Pot project and, until I was fourteen, I was embarrassed by my parents’ accents. People are often surprised, seeing me as a champion of cultural pride; but this identity was something developed over time.

My writing addresses U.S. imperialism at the turn of the 20th century – specifically, the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, where over 1,200 Filipinos were displayed. During this period, magazines ran cartoons portraying Filipinos as minstrels, “savages,” recalling more familiar racist portrayals of African Americans.

(Source: "The Forbidden Book" by Jorge Emmanuel and Abraham Ignacio)

As a preface to discussing my work, I often say to my listeners, “This is American History.” We know America is no monolith. But until we see the complex historical relationship between the United States and the Philippines and the challenges and triumphs of Filipinos in America – Filipino Americans remain marginalized as “invisible” or the “Forgotten Asian Americans” rather than the resilient, revolutionary people we have always been.

Until we broaden our sense of American History – including the varied stories of all of our populations, then the limited, often-xenophobic version of American history remains incomplete, even dangerous. Until we decentralize the narratives, in and beyond textbooks, we carry on the language of the colonizers, leaving “minority” groups with the burden to explain, remind, and justify our very existence. The United States has a long way to go in re-conceptualizing its own identity.

I think: Why am I still expected to represent “my” people? Shouldn’t YOU be reciting these histories, too? This goes not only to my white friends, but to my fellow Pinoys and other people of color, whose histories all intertwine with my own.

A display of images from the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair at Missouri Library Museum (Photo by Aimee Suzara)

It is our job as writers, artists and educators to help young people see themselves reflected in centralized parts of the curriculum and literature, not just in the footnotes. And it is the job of everyone else to carry the load, shifting and expanding the conversation.

I write for that student who felt bewildered about her place in the world and asked a question, but was shut down and silenced.

I write and I speak to tell her: Keep asking, and don’t let anyone shut you down. Your stories are essential. Your story is Filipino History, and it is American History. Keep speaking, and they will listen.

Aimee Suzara's mission is to create poetic and theatrical work about race, gender, and the body to provoke dialogue and social change. www.aimeesuzara.net