They Blazed a Path for Us

/(L-R) Positively Filipino publisher Mona Lisa Yuchengco, Velma Veloria, Rozita Lee, Vangie Buell, emcee lloyd LaCuesta, Peter Jamero, Joe Bataan, Dorothy Cordova and Alex Fabros, Jr. (Photo by Minerva Amistoso)

So, last August 31, Positively Filipino paid tribute to 12 outstanding manongs and manangs who have paved the way for us to have a better life in America, whose shoulders we proudly stand on.

Their stories are testaments to the hardship, discrimination, racism, and inequality they personally witnessed, endured, and overcame in order to give their families a better future. From politicians to academicians, from historians to musicians, from artists to activists, they have blazed a remarkable path for us.

In a world where technology is replacing almost every aspect of human life -- where phones have replaced real conversations, where time is so hurried, where kindness is a rarity -– let’s stop for a moment to pay our respect to our elders. It’s time to hear their stories and embrace the important lessons they can share. It's time to say a big “Thank you!”

Positively Filipino will continue to tell the stories of the manongs and manangs, lest we forget. -The Publisher & Staff

Belinda Aquino by Fred Magdalena

Belinda A. Aquino

Belinda A. Aquino’s life story is uncommon among Filipinos. The youngest among her siblings, she was raised in a middle-class family from San Fernando, La Union. Her father was the town mayor, her mother a nurse-to-be. Growing up and studying in a village or barrio populated by Ilocanos shaped her world, where children lived in tranquility, obedience to family, and a bahala na or come-what-may outlook.

Fondly called Lindy by friends, she broke from tradition when she decided to study at the University of the Philippines to pursue a BA in English. In that new world, she was exposed to a multicultural setting where students came from different places and spoke other languages. Her dorm roommates were Visayans from Mindanao, whose culture was different from her regional identity. Her mother constantly visited her with food, a reminder of love, connection, and a strong family that gave assurance to a favorite bunso (youngest daughter) studying far away from home.

Life as a university student exposed her to a new life, learning about activism besides lessons in classrooms. She became polished as a scholar with the East-West Center, earning an MA in Political Science at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Deepening her immersion in this field, she went to Cornell University for her PhD in Governance. Both academic fields were her father’s legacy as a politician, but something more radically political changed her life narrative.

Dr. Aquino and Anti-Marcos demonstrators (Source: Filipino Chronicle)

At the time, the Philippines had an Ilocano president, Ferdinand Marcos, who imposed a dictatorship in September 1972, using the left and Muslim rebellions as pretext for doing so. Lindy and other Filipino activists on the East Coast organized a conference to expose Martial Law as a power grab. Lindy saw her name on a “blacklist” of the 150 student participants; the Philippine government canceled her passport, preventing her from going back home. She has remained in the United States to this day.

Being in Hawaii was a blessing in disguise for Lindy. A pro-bono lawyer and then-Senator Daniel Inuoye) helped her get a permanent residency. She soon joined the UH faculty and became founding director of the Center for Philippines Studies in 1975, an important learning institution for Filipinos both in the homeland and the diaspora. It was the only center for Philippine studies in the United States. At the Center, she established four endowments, the first being the Alfonso Yuchengco Endowment Fund that granted research scholarships to students.

“When I refer to ‘Kumander Lindy,’ I do so out of respect,” says Jojo Abinales, a fellow UP graduate and UH professor, “for she has combined scholarship with a deep love for democratic politics.” In the heyday of the Marcos dictatorship, Abinales and colleagues in the Philippines would receive by mail cut-outs of her columns and “were comforted by the fact that in those dark days, we knew people abroad had kept the fight as we did back home.”

Publishing books and writing articles in prestigious journals, Lindy had a column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer. Organizing international conferences were among her countless scholarly achievements. She is recognized internationally as a foremost authority in Philippine studies. She retired in 2019 and today is on the university’s pedestal as Professor Emeritus.

She would like to be remembered as a Filipina stranded in Paradise, whose heart is left in the homeland. Her one personal regret is not having enough time spent with her parents. Among eight children, she was the only one “who got away.”

Dr. Aquino in Waikiki (Photo courtesy of Rose Aquino)

“It is our responsibility as researchers, teachers, and scholars to provide vital sources of knowledge to clarify, advance, and help resolve problems and issues facing humanity,” Lindy affirms. “I would like to think that my main legacy lies in my contributions to academia, as well as my role in the pro-democracy movement in the U.S. Society continues to change. So, the job of furthering knowledge must always continue.”

Joe Bataan

Joe Bataan (Photo courtesy of Joe Bataan)

Born Bataan Nitollano in 1942 to an African American mother and a Filipino American father, Joe Bataan is known as the King of Latin Soul.

Joe Bataan's parents (Source: Asian American Life)

Growing up in Spanish Harlem in New York, Bataan got involved with a Puerto Rican street gang and ended up at the Coxsackie Correctional Facility to serve time for car theft. It also there where he vowed to change his life completely, and upon his release, turned his attention to music, forming his own band combining doo-wop with Latin rhythms. His first release, Gypsy Woman, caught the attention of Fania Records.

Later on, he formed his own recording outfit called SalSoul and released Afro-Filipino to embrace his identity. He retired from music-making to spend more time with his family and became a youth counselor in one of the reformatories he himself had spent time in as a teenager. After a 20-year hiatus from the music industry, Bataan returned in 1995. He released a new album titled Call My Name in 2005.

In 2012, Bataan visited his father’s homeland, the Philippines for the first time. Like many Filipino immigrants, his father was never able to fulfill his dream of returning home.

In 2013, Bataan received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the New York chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society. He was also honored by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, highlighting his career and the socio-cultural activism of Asian, Latino, and African communities in the sixties and seventies. His photo hangs with the likes of Maya Angelou and Dizzy Gillespie.

FAHNS founder Dorothy Cordova and Joe Bataan (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Joe Bataan and his band featured at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Bataan continues to perform all over the world. He is still a youth counselor, teaching the three ingredients of success: spirit (believing in a Supreme Being bigger than yourself), health (taking care of your body), and knowledge (learning something new every day).

Reflecting on his life, the 82-year-old artist is quick to embrace gratitude. “I’ve always been an underground commodity,” he said. “I’ve never been Elton John, I’ve never been Michael Jackson. Joe Bataan has always been underground. But my public is spread throughout the world and my songs have captured a lot of hearts through my lyrics, and I owe that gift to God.”

His upcoming memoir, Streetology: The Legacy of the Afro-Filipino King of Latin Soul, will attempt to capture his ongoing story. Bataan summarizes his journey as a “Cinderella story.” He not only turned his life around after prison, but he also survived a host of ailments including three heart attacks, cancer, and diabetes. His health scares have influenced the way he performs on stage. “I open up all my concerts with The Lord’s Prayer, and that was a promise I made maybe 25 years,” said Bataan, who didn’t realize when he recorded the song four decades ago that it would become his most popular.

Vangie Buell by Evelyn Luluquisen

Evangeline Canonizado Buell

Evangeline Canonizado Buell's life unfolded amidst diverse cultures, inescapable historical forces, and timeless traditions. Born to a father from the rugged coastlines of Zambales province and a mother from the fertile rice-growing region of Nueva Ecija, her lineage is a rich tapestry of Filipino and African-American histories and heritages. Her Ilocano father served in the U.S. Navy, and her mother was the Tagalog daughter of a Buffalo Soldier and a Filipina. Her parents met in the vibrant neighborhood of West Oakland, a gathering place for Filipino women and their African-American husbands who had served in the Philippine-American War.

Vangie’s love for music blossomed under the guidance of her parents. Her mother strummed the guitar, teaching her lilting Filipino children's songs like Planting Rice, while her father who played cornet in the U.S. military introduced her to the soulful melodies of jazz legends like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and Billy Eckstein.

"In order to be average, you have to be excellent," her father would say, underscoring the importance of education in achieving one's dreams in a society stricken with discrimination. Vangie took this to heart as she studied at San Jose State University and University of San Francisco. Her step-grandmother, taught her to embrace diversity, advising, "We must accept all people who work with their hands, not just look up to rich people." Mrs. Wilson, her teacher at Cole Elementary School, helped her find pride in her name, while Ms. Helen Black at McClymonds High School fostered cultural understanding through the universal language of food. In her classroom, students learned to prepare dishes like tacos, spaghetti, blitzens, lumpia, and cornbread—culinary celebrations of their diverse backgrounds.

Yet, Vangie's journey was filled with struggles that required an unrelenting belief in her worth, human rights, and dignity. During World War II, every Filipino was required to wear a red, white, and blue badge proclaiming themselves as a "Loyal American - Filipino." Once, forgetting to wear it, she was refused service in a store. On trips from Oakland to the Central Valley, her family could only dine in Chinese restaurants due to signs declaring, "No Dogs or Filipinos Allowed.

"No Dogs Allowed" (Source: "No Dogs")

In the 1950s, a state trooper doubted the legal marriage of Vangie and her first husband, under then-existing anti-miscegenation laws. in the 1960s, a supervisor told her she should stay home as a single mother with her children rather than work. In the ‘70s, she won a job discrimination lawsuit after being unfairly demoted.

Despite her shyness, she was drawn to people and their stories, particularly their music. Her first husband taught her to play the guitar, and just before marrying her second husband, she was invited to tour with the Bay Area Gateway Singers, later known as the Limelighters. She taught guitar at Berkeley Cooperative Inc. (Co-op) and directed a wildly successful Hootenanny in 1965, featuring 20 of her students and Lou Gottlieb of the Limelighters. She was later an events coordinator at the International House at the University of California, Berkeley, thriving in the multicultural environment with students from around the world. She authored Twenty Five Chickens and a Pig for a Bride, 7-Card Stud and 7 Manangs Wild, Beyond Lumpia and Filipinos in the East Bay.

Vangie’s legacy as a mentor and community leader has touched thousands, encouraging individuals to connect with and embrace their cultural heritage. She continued this mission through her jobs at Co-op and the International House, volunteer work with the Berkeley Arts Commission, Oakland Museum, Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), and now the Piedmont Gardens Hootenanny Ensemble. She firmly believes that self-esteem is greatly influenced by ethnic pride and understanding one's history and culture handed down through generations.

The Piedmont Gardens Hootenanny Ensemble

Ben Cayetano by Rose Churma

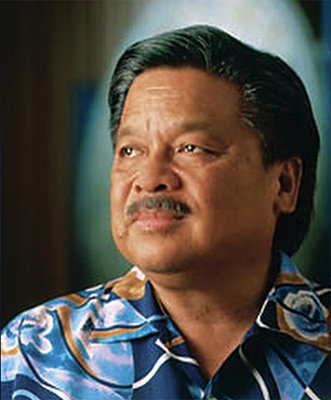

Hawaii Governor Ben Cayetano

Ben Cayetano is the first Filipino American to serve as governor of Hawai’i and the first of Filipino ancestry to hold a governorship in the United States. In his memoir he writes, “We are all creatures of our experience. Our upbringing, parents, ethnicity, and culture all shape us in some way.”

The autobiography helps define his legacy and is also considered one of the most important books on Hawai’i politics. It reveals Ben as a complex human being brutally candid about himself and those around him, who has an innate toughness due to his hardscrabble childhood, and a keen intellect, and a curiosity about the world beyond his Kalihi neighborhood.

He was born in 1939 when Hawaii was still a US territory, when one’s ethnicity pre-determined one’s career prospects. At the time, Filipino Americans were at the bottom of the very pronounced the ethnic pecking order.

His immigrant parents divorced when he was six, and his dad as a single parent raised him and his younger brother. He would later find out that his dad was not his biological father. He treated him as the only father he ever had. Ben and his brother Ken, took care of him after dementia set in, looking after him until his death.

Ben's father (left), Ben and brother Ken, and his mom.

Ben’s mom, who at one point owned and managed a dance hall, was one of the strongest persons he ever knew, whose grittiness came from her upbringing. However, her fortitude was destroyed by addiction to drugs legally prescribed by her doctors. He also wrote of his brother Ken’s homosexuality. A Vietnam veteran and a model citizen, Ken’s relationship with his partner has endured and he remains happy and productive to this day.

Ben got married soon after high school and needed to support his family by working as a station attendant, truck driver, draftsman, electrician’s apprentice, among others, until it dawned on him that education was his way out from dead-end jobs. In 1963, he uprooted his young family and moved to California to earn a degree in political science, finishing at UCLA in 1968, and a law degree from Loyola Law School in 1971.

His life experiences informed his decisions in public office. As governor, he supported same-gender rights, doctor-assisted suicide, gambling, and medical marijuana that put him at odds with many of his contemporaries. He holds the distinction of being the only Hawai’i governor to see both Native Hawaiians and public-school teachers holding protest signs reading “F–K Ben.”

Protest against Gov. Cayetano

However, he kept his promise to make public education a high priority. As governor, he spared the schools from budget cuts at the expense of other state departments but sought reform through the collective bargaining process. He negotiated a contract in 1987 that increased teacher salaries in exchange for adding seven days to the school calendar.

As the lieutenant governor, Ben established the popular A-Plus, a statewide government-sponsored after-school program that accommodated children of working parents, tremendous help from a former latchkey kid who understood the program’s importance to families with young children.

He served in the Hawaii House of Representatives from 1975 to 1978, the Hawaii State Senate from 1979 to 1986, as lieutenant governor from 1986 to 1994, and as governor from 1994 to 2002.

Ben has received his many awards for his work including the Distinguished Leadership Award from UCLA’s John E. Anderson Graduate School of Management in 1995, Hawaii Chapter of the American Society of Public Administration’s Award for Ethics in Government in 1995, an award for leadership and contributions to American government and intercultural relations from the Harvard University’s Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations in 1996, and many more.

He was chairman of the Western Governors’ Association, but also appeared as himself in the bikinis-and-beach TV series Baywatch. He got divorced while in office and married Vicky Liu, a successful entrepreneur who was once a child star in an Elvis Presley movie. Today, they live quietly and comfortably in one of Honolulu’s wealthiest neighborhoods with their pet dogs.

Ben, Vicky and their dogs

Ben Cayetano is an American success story, who achieved his dreams and made a difference. More importantly, he’s an inspiration, not only to Filipino Americans, but also to all who come from underrepresented minority groups across the United States.

Dorothy Cordova by Bibiana Shannon

Dorothy Cordova

Dorothy was born 1932 in Seattle to two immigrants from La Union. Her extended family was one of the largest pioneering Filipino families in Washington State. She grew up during the Great Depression and World War Two – experiences that impacted her life.

She married the late Fred Cordova in 1953 and for most of their 60 years together, they organized and developed two organizations to uplift Filipinos – the Filipino Youth Activities of Seattle and the Filipino American National Historical Society. Imbued with a Catholic sense of social justice, they fought for civil rights during the hectic 1960s and 1970s.

Dorothy and Fred Cordova (Source: FANHS)

As lead researcher for the Demonstration Project for Asian Americans, she wrote proposals to meet the needs of young people and recent immigrants. Dorothy became a historian by default when in 1973 the Washington State Department of Archives and Records asked her to head a statewide oral history project on pioneer Filipinos. In 1979, she submitted a proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities for a two-year national history project Forgotten Asian Americans: Filipinos and Koreans.

When funding ended in 1982, she began plans for a volunteer non-profit organization, the Filipino American National Historical Society. Today, there are 45 chapters in 21 states and Washington D.C that gather regularly to share both local and national history. For 42 years, she has served as the volunteer Executive Director of FANHS.

Dorothy was an Affiliate Assistant Professor of American Ethnic Studies at the University of Washington. For ten years she was on the Board of Regents at her alma mater, Seattle University, which later bestowed honorary doctorates on her and Fred in 1998.

Fred and Dorothy Cordova (Source: FANHS)

Dorothy is the mother of eight, grandmother of 17, great-grandmother of 26, and great-great grandmother of one, and the grandmother of the entire Filipino American community.

Alex Sandoval Fabros, Jr. by James Sobredo

Alex Fabros, Jr. (Source: Facebook)

In 1946, the year that the Philippines officially became an independent nation. Lt. Colonel Alex Fabros was born in a nipa hut in Nueva Vizcaya, Cagayan Valley, Luzon, in the Philippines.

He is “Lt. Colonel Fabros” because that is the highest rank he reached in his distinguished military career. However, because of bureaucratic rules, he officially retired with the rank of Major, but, more importantly, received the retirement pension of Lt. Colonel, which is two ranks from general.

Alex’s father, Alex de Leon Fabros, was a member of the famous 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments in the US Army and served in the Philippines in World War II. The unit received the Congressional Gold medal in recognition of their distinguished service.

While in the Philippines, Alex de Leon Fabros met Josefina Sandoval. A year after they were married, Alex Sandoval Fabros Junior was born.

Alex de Leon Fabros and Josefina Sandoval with their son Alex Fabros, Jr.

The young family eventually immigrated to America in 1948 and settled in the farming community of Salinas where his father purchased a home. Alex also grew up in Germany, where his father was assigned for four years. Upon returning to Salinas, he floundered academically (perhaps due to boredom) and ended up working in the farmlands of the Central Valley alongside Filipino manongs and other farm workers, which is how he met Mexican farmworkers and UFW founders Larry Itliong, Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez.

Fabros with labor activist Dolores Huerta

In 1965, Alex was drafted into the US Army but ended up enlisting in the US Marine Corps—he tells a funny story on Facebook about how this strange recruitment happened. Young Alex Fabros was a combat veteran who experienced the full horrors of war, or as he wrote in his recollections of his time in Vietnam: “We lost our youth, and we lost our innocence.”

When his service obligations ended in Vietnam, he was given a very enticing recruitment option by a military recruiter: if he reenlisted, he could become an officer. Thus, he reenlisted into the US Army.

Fabros with fellow soldiers

He was able to attend officer candidate school, became an Army officer, and remained in the US Army, until he was medically discharged in 1992 due to medical complications from his military duties and exposure to Agent Orange. By this time, he had reached the rank of Lt. Colonel and have had assignments all over the world.

While in the Army, Alex attended the famous Defense Language Institute in the Presidio in Monterey, where learned to speak Chinese (Mandarin), Vietnamese, Japanese, and Korean. He returned to Vietnam and worked as a specialist in military intelligence and counterinsurgency, which lead him to a colorful, fascinating, and exciting life of military intelligence, spies, and counterespionage. He also dabbled in “automation,” which meant computers: This Filipino farm boy from Salinas was responsible for multimillion dollar contracts and transitioning the Army to using modern computers. Remarkably, he never formally finished an undergraduate college degree.

After his retirement, Alex went on to receive a formal education with an M.A. in Ethnic Studies from San Francisco State University, attended UC Berkeley on a fellowship, and received a President’s Fellowship at UC Santa Barbara for his Ph.D. in history. He went to teach Ethnic Studies as a faculty member at San Francisco State University. He was featured in several PBS documentaries, including the epic Asian American five-part series aired in 2020 that highlighted his life story and experience as a farmworker and Vietnam veteran. Alex was also the director of a major museum exhibit on Filipino American history at the Steinbeck Center in Salinas, as well as founder and director of the Filipino American Experience Research Project that digitized the records of the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments and Filipino American newspapers. He has written numerous articles for Filipinas Magazine and Positively Filipino.

Fabros with his wife Lorraine

In his retirement years, Alex remains active as a scholar and historian. He enjoys photography, writing, traveling, and spending time with his wife Lorraine, whom he met in San Francisco, as well as spending time with his daughters Kathy, Jenny, Alexandra, Michelle, his son, Allan, and his grandchildren. He is also likely the only Filipino who has sailed from San Francisco to Mexico and on to Hawaii, and then all the way to Tahiti.

Dan Inosanto

Dan Inosanto

Dan Inosanto, who grew up in Stockton, California, began training in martial arts at the age of 11, receiving instruction from his uncle who first taught him traditional Okinawan Karate and later also Judo and Jujutsu. Inosanto is known for promoting Filipino martial arts. He is responsible for bringing several obscure forms of Southeast Asian martial arts into the public eye, such as Silat, a hybrid combative form existing in such countries as Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Dan Inosanto and Bruce Lee

Inosanto is best known as the training partner of Bruce Lee. He is an authority on Jeet Kune Do and Filipino Martial Arts including Escrima and Pencak Silat. He related in the film, I Am Bruce Lee, a little-known fact about the friendship the two men shared; that he was the teacher to Bruce Lee, introducing the nunchaku to him. Inosanto explained, “Bruce’s original concept for Game of Death was to educate the film-viewing public by making people aware that there are many different types of martial arts and that each martial art has a value in a certain environment.”

In Enter the Dragon, Lee demonstrates Escrima, using double baston (double sticks) to subdue the guards.

Dan Inosanto on the cover of black Belt Magazine

Inosanto was featured as the Black Belt Magazine's 1996 "Man of the Year." Contributing editor Dr. Mark Cheng writes: “The Filipino system taught by Dan Inosanto is far more than just the sticks and knives that the casual observer sees. Including every possible weapon and range of combat, Inosanto's system is one of the most sought-after and imitated in the world when it comes to practical self-defense.”

Inosanto is a four-time Black Belt Hall of Fame inductee, putting him in the same category as Chuck Norris, the only other martial artist who has been inducted four times. He has taught many famous students like Denzel Washington and Forest Whitaker.

He has also published several books on martial arts. He was also commissioned by the Dallas Cowboys to incorporate martial arts into the team’s training. Dan Inosanto currently operates a martial arts school in Marina del Rey, California.

In an interview with Aikido Journal, he said, “For me, martial arts are really about bringing people together. I learn the culture of a country through the martial arts. When I study a Korean art, I learn something about Korea. When I study a Japanese martial art, I’m learning about the history and culture of the Japanese. Learning about other people and other cultures brings people together and creates greater understanding among people.”

He adds: “Be kind, be courteous and respectful, and avoid negative people because they’re really not good for the soul. Eat as healthy as possible, take care of your body and mind, and learn to adapt. Find your place in this world and seek connection with your spirituality – whatever form that may take.”

Peter Jamero by Julie Jamero Hama

Peter Jamero

Peter Jamero was born in Oakdale, California in 1930 and raised on a Filipino farm worker camp run by his parents in nearby Livingston. He spent four years with the U.S. Navy and saw duty in the Korean War.

In 1953, he married Terri Romero and they have six children. He attended San Jose State and UCLA where he received a master’s degree in 1957, and he attended Stanford University as a Public Affairs Fellow in 1969-1970.

Peter and Terri Jamero

Peter became a top-level executive in health and human service programs in federal, state, and local governments, and in the private non-profit sector in Washington and California. Some of his positions included: assistant secretary of the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services; director of the Washington State Division of Vocational Rehabilitation; director of the King County (WA) Department of Human Resources; vice president of the United Way of King County; executive director of the San Francisco Human Rights Commission; assistant professor of Rehabilitation Medicine of the University of Washington; branch chief in the U.S. Department of Health; Education and Welfare in Washington, D.C.; executive director of the Asian American Recovery Services in San Francisco; executive director of Mental Health Association and Boys and Girls Club in Merced; and Division Chief, Sacramento County Department of Social Welfare.

Jamero’s autobiography, Growing Up Brown: Memoirs of a Filipino American, his story of hardship and success, illuminates the experience of the “bridge generation” – the American-born children of the Filipinos recruited as farm workers in the 1920s and 1930s. “Their experiences span the gap between these early immigrants and those Filipinos who owe their U.S. residency to the liberalization of immigration laws in 1965.” His book is “a sequel of sorts to Carlos Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart, with themes of heartbreaking struggle against racism and poverty and eventual triumph.”

Peter and Terri Jamero

The Jamero family

Peter lost his wife Terri in 2009 after 56 happy years of marriage. Retired since 1995, Peter lives in Atwater, California. At 94, he spends most of his time listening to jazz, following the New York Yankees, doing yard work, solving crossword puzzles, and being a loving father to his six children and doting grandfather to his 15 grandchildren. His latest book, Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation, was published by University Press of America in 2011. Every month, Peter publishes Peter’s Pinoy Patter, a newsletter on the Bridge Generation and other updates on the Filipino American community.

Rozita Lee by Corin Lujan

Rozita Lee

Rozita Villanueva Lee served on President Barack Obama's Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders for four years. She was Nevada Governor Bob Miller’s Special Assistant, the first Filipina and Asian Pacific American to be in the Governor's office in the history of Nevada.

She has helped organize huge rallies advocating Comprehensive Immigration Reform, walked the Halls of Congress, seeking support for the World War II Filipino Veterans Equity Bill and Congressional Gold Medal of Honor for them. Today she continues advocating for Filipino Veterans of WWII along with Maj. General (ret.) Tony Taguba, this time to repeal the Rescission Act of 1946.

While serving as president of the prestigious Women's Democratic Club of Clark County, she was also president of the Ilocano American Association of Nevada as well as Chair, Regional Chair, and National Vice Chair of the National Federation of Filipino American Associations –NaFFAA. In Las Vegas, Rozita spearheaded educational workshops and rallies and held town hall meetings and summits for AAPI communities. She also facilitated free screenings for Hepatitis B with Dr. Noel Fajardo.

Rozita Lee speaks at a "Stop the Hate" rally in Nevada (Photo by Corin Lujan)

Rozita Villanueva Lee was born in Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii. Her immigrant parents, Leoncia Asuncion and Eugenio Estrada Villanueva, were brought to Hawaii by the Hawaii Sugar Plantation Association in the early 1930s from San Manuel, Pangasinan along with hundreds of others from the Philippines. Lee is the seventh daughter, the buridek (youngest) of the family.

She received her education at the University of Hawaii and University of Nevada, Las Vegas where she received her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Communication Studies and went on to work on her master's in the same field and taught Speech and Television Production. She was a radio personality on KISA RADIO and had a television program Hawaii Now on PBS station KHET. In 1972, she flew to the Philippines to interview people as well as President Ferdinand Marcos about Martial Law. The Governor of Hawaii named her to the Commission on the Status of Women, the first Filipina to that body. She also helped establish the United Filipino Council of Hawaii and was chair of the Miss Hawaii Filipina Pageant for 10 years.

Rozita Lee in the studios (Source: facebook)

Rozita was first married to the late Moeses Luis Yuzon. They had three children, Byron, Craig and Roxanna Yuzon Ayakawa. Lee later married her longtime friend Dr. Clifford Lee, a beloved Doctor in Las Vegas. He passed away 17 years ago. Lee is a proud grandmother of 11 and great grandmother of 22. She is an ordained pastor at Seek Jesus First Ministries, advisor for many organizations, and has an honorary doctorate in the Humanities from the United Graduate College and Seminary International.

Rozita Lee's family

She was the only person invited to accompany the late U.S. Senator Harry Reid to meet with then-President of the Philippines Gloria Arroyo and her cabinet when he received an Award for his advocacy for the WWII Filipino Veterans. Rozita Lee’s advocacy for her community continues.

Rozita Lee on the street bearing her name: Rozita Lee Avenue

Dolores Sibonga by Ador Yano

Dolores Sibonga

Dolores Sibonga, the first Filipino and the first woman of color to be elected to the Seattle City Council, considers herself a child of the city’s historic Filipino Town. The daughter of Filipino immigrants, Maria Dasalla and Victoriano Estigoy, Dolores grew up in Seattle’s International District where her family moved to run a pool hall and the restaurant Estigoy Café in the 1930s.

Growing up in her family’s restaurant business she remembers the Cafe, the hotels, barbershops, grocery stores, gambling halls, the streets and alleys of her Seattle childhood. She remembers the manongs bringing home salmon cheeks that were throwaways from the Alaska canneries. She knew they were people who worked hard but often received little in return. But she remembers them as joyful and generous, the core Filipino qualities she treasures. She does not forget the summer nights when the young Filipino men would gather at the Cafe to play guitar, mandolin, and violin and sing the sweetest harmony in songs of home and romance. She learned hope, determination, and respect for others from them. She acknowledges these early life-affirming experiences that have informed who she is and what she has accomplished. Dolores was nurtured by family and friends whose dreams and aspirations became her own.

Filipino cannery workers

Dolores married Martin Sibonga and raised a family of three children – Theresa, Martin Jr, and Randi. A journalism graduate of the University of Washington, she initially pursued a career in radio and television. The economic downturn resulting from Boeing’s layoffs in the early 1970s created family difficulties that she turned into an opportunity. Motivated by the Civil Rights Movement, she attended the University of Washington Law School.

Dolores and Martin Sibonga

The Sibonga Family

In 1973, she earned her law degree and became the first Filipino American to be admitted to the Washington State Bar. Sibonga became a public defender representing poor clients who were mostly people of color with minimal resources. She then served as Deputy Director of the Washington State Human Rights Commission.

In August 1978, Dolores was appointed to the Seattle City Council. Sibonga wanted to expand the visibility of Asians in decision-making positions and to be a leading advocate for minority interests. Her initial appointment and later victories in three elections were historic milestones. As the first Filipino and the first woman of color to serve in Seattle’s City Council, Dolores led the effort for the first Affirmative Action plan for the city, as well as the first economic development plan that emphasized opening employment opportunities for women and people of color.

She continued to serve the community after leaving the City Council, joining the board of the Wing Luke Asian Museum and advising the Filipino American Political Action Group of Washington.

Dolores Sibonga’s legacy is inspiring others to live a life of passion for justice and service for others. She has done it gracefully while, along the way, making history for Filipino Americans in Washington state. She is an exemplary model of sustained activism, one based on the values of “Hope, Determination, and Respect for Others, values she learned from the manongs of her childhood in Seattle’s Filipino Town.

Dolores Sibonga

David Valderrama by Jon Melegrito

Judge David Valderrama

David Mercado Valderrama served as a Democratic member of the Maryland House of Delegates from 1991 to 2003 and was the first Filipino and Asian American elected to a state legislature--the Maryland General Assembly--in the mainland United States. He inspired many Filipino Americans to run for public office. Among them is his daughter, Kris, who is now serving her fifth term as Maryland Delegate.

David Valderrama and daughter Kris, with Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley

David fought for inclusion of Asian Pacific Americans in affirmative action programs and was a consistent advocate for immigrant rights. He sees himself as a politician who would continue to prioritize APA interests.

"When I first got here in 1961, most Filipinos told me they'd never really experienced discrimination. But my God, I experienced it, knocking on doors, looking for living quarters. People were really condescending.” Angered by the racism he faced, he joined the civil rights movement, marching, picketing and passing out leaflets, identifying with the plight of Black Americans.

Being a political figure who is unwilling to play safe from controversial issues, David was an outspoken leader in the opposition against the Marcos dictatorship. He also took part in demonstrations in front of the South African Embassy against apartheid and was the first Asian American to be arrested for protesting there in December 1984.

Valderrama at an Anti-Marcos rally

A law graduate from Far Eastern University in Manila, David came to the U.S. in 1961 to advance his studies. Instead, he was enticed by a Library of Congress legal-writing job. Besides his political career and advocacies on behalf of democracy and justice, his background spans journalism, business, banking, legal research and analysis. The second youngest of nine children, was a precocious child and grew up fast, going into business for himself at 16, peddling everything from cars to cigarettes. These experiences prepared him well for probate and guardianship judiciary functions and armed him extensive knowledge of property rights tempered with a sensitivity to human rights.

He first broke into U.S. politics while managing his own Montgomery County-based company publishing a television newsmagazine. He was also a reporter for the U.S. Information Agency, which aired his interviews in Manila. Members of the Filipino American community urged him to run for the Prince George's County Democratic Central Committee delegate seat in 1982.

(Source: Katipunan)

His mother was also an inspiration: "My mother surprised me when she said she was pro-choice. She told me she saw so much misery among young women in the Philippines--so many unwanted pregnancies. She rebelled against the Catholic Church. Her conviction had a strong impact on me as a legislator."

David was only nine years old when he learned the high price of idealism. In 1942, when Manila was under Japanese occupation, David's father risked his life resisting the Japanese puppet government and secretly financing anti-Japanese guerrillas. Refusing to be a collaborator, he was arrested and executed by the Japanese; his body was never found. "The lesson I learned from that is that you stick to your beliefs no matter what, come hell or high water. My father was a man of principle. There's got to be justice in the world. So, when I came to the US and saw racial discrimination, I became even more determined to fight injustice."

David Valderrama with Bing Branigin (left) and Jon Melegrito (right)

David Valderrama’s advice to compatriots: “Somebody’s got to open doors. My father did it for the guerillas in our area. I look at that as a strong inspiration. When I spoke before Asian Americans in LA, they kept asking me how I’ve been able to do it here. And I tell them, ‘coalition-building among Blacks, Hispanics, Asian Americans.’ It’s hard work. And you have to sweat.”

Velma Veloria

Velma Veloria

Velma Veloria in 1992 became the first Filipina in the continental United States to be elected to a State Legislature, serving 12 years representing South Seattle’s 11th District. Besides advocating for affordable housing, workers’ rights, and racial justice, she put a spotlight on the impact of international trade and globalization on local communities and co-authored important legislation combatting human trafficking and requiring oversight of international trade agreements.

As a member of the State Legislature, she worked with the UW Womxn’s Center for the passage of HB 1175 criminalizing human trafficking in Washington, after the shooting of three Filipina Americans in the King County courthouse.

Velma fought to regulate the mail-order bride “industry” in Washington by requiring such operations to have documented proof of registration and payment of taxes. Forty-States passed similar legislations. She also ensured the completion of the Filipino Community Village, a 94-unit affordable senior housing with an Innovation Learning Center.

Velma Veloria raising awareness against human trafficking

Velma was born in Bani, Pangasinan, Philippines and immigrated to the United States in 1962 at 11 years old, the eldest of four children. Her father served in the U.S. Navy. Within a year of the family’s arrival, her mother died of cancer. Velma took over most of the household chores and caring for her siblings. Her father worked as a breakfast cook at a drive-in restaurant. They were considered part of the “working poor.”

She has a Bachelor of Science degree in Medical Technology from San Francisco State University. She became an activist in the anti-war and Asian American movements, learning about the history of Filipinos in America and the discrimination they faced. "When you're taught U.S. history, you're not taught about the contributions of people of color. You begin to dislike being Filipino. I was able to take more pride in my cultural heritage," she said.

Upon graduating from college, Velma traveled to the Philippines, where she saw the brutality of the Marcos regime. When she returned to the United States, she joined the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP), or Union of Democratic Filipinos, to oppose Marcos and end U.S. support for the dictatorship.

She also became a labor activist through the ‘70s and ‘80s, working as an internal organizer for the Office of Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU), ILWU Local 37 (cannery workers), and in Service Employees’ International Union (SEIU) office worker and nurse organizing drives in San Francisco, New York, and Seattle.

Filipino cannery workers posting with Steve Gillon (back), a machinist. (Photo by Tom Connelly)

Following the assassination of ILWU Local 37 officers and KDP activists Gene Viernes and Silme Domingo on June 1, 1981, the organization transferred her to Seattle to help bolster the union reform movement in the Alaska cannery industry. For the next few years, Velma organized cannery workers, joined the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Viernes, and continued to agitate against the Marcos dictatorship. Like many KDP activists after the downfall of the dictatorship, Velma put her political energy into Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition presidential campaign in 1988. She then became a Legislative Assistant to State Representative Art Wang.

Velma also was active in other nonprofit organizations such as Faith Action Network and the Coalition of Immigrants, and Refugees and Communities of Color. In 2019, the University of Washington (UW) welcomed Velma, Director of Advocacy and Mobilization for the Equity in Education Coalition, as its first Honors Curriculum and Community Innovation Scholar. During her two-year stint at UW, she mentored students in community organizing, worked to eliminate racial and economic disparities within primary education, and created an anti-human-trafficking course.

Velma Veloria continues her activism to “ensure that we live in peace and social justice.”