The Wacky 1978 Chess World Championship

/Lost somewhere in there is Chess, a more cerebral challenge. And this would be as good a time as any to recall the chess World Championship of 1978 held in Baguio City, the Philippines, and will be coming up for its 40th anniversary next year.

Those 1978 championships set some sort of record for a series of bizarre stunts and even more wacky reactions from the opposing camps. They have been acknowledged, especially in chess history books, as the Most Bizarre and Zany World Championships of all. Baguio 1978 consisted of a series of eccentric, one-upmanship antics by the two sides centered mainly on setting up the playing stage and trying to gain some minute edge over the other.

That 1978 championship happened six years into the Marcos martial law years and, because it was low on then-first lady Imelda Marcos’ list of “bread and circuses” extravaganzas, it is often forgotten. Caught in the middle of all that craziness was one Filipino promoter who was able to turn the circus into a springboard for higher aspirations, making a name for himself in the narrow world of international sports organizations and sports event management.

There are two things to remember when trying to understand the world of chess. One, the sport is controlled by FIDE, Federation Internationale des Echecs (or the World Chess Federation), founded in 1924. In 1946, it was promulgated that FIDE-sanctioned World Championships take place every three years.

The FIDE logo and its motto, “We are One People.”

Thirty (30 sentimos (cents)) commemorative stamp issued for those 1978 World Championships.

Two, the Russians, especially in Soviet days, dominated the sport. Even though FIDE is based in Switzerland (as most of the international sports federations are), the ranks of the chess grandmasters have always been heavily Russian. Chess is as much a part of the Russian DNA as poetry, long Siberian winters, rhythmic gymnastics and pairs-figure skating. Since the end of World War II and until a few years ago, the list of world champions has always been Soviet/Russian, and American Bobby Fischer was the only one to have broken that streak in 1972.

Even after Fischer resigned/recused himself from the 1975 championship (originally intended for Manila), the two challengers for the 1978 title were still Russian/Soviet citizens. Heir-designee was Anatoly Karpov, and the challenger was defector Viktor Korchnoi who left the USSR in 1976. At the time of the tournament in Baguio, Korchnoi’s residency in Switzerland was not quite settled.

The 1978 championship turned into an opera bouffe—with a lot of logistical, pre-match posturing with one side trying to rattle the other. When all was said and done, most of the bizarre, peripheral antics really bordered on the petty. To wit:

The Decorative Pageantry Fuss (i.e., display of flags): Since defecting in 1976, Korchnoi had not established enough time in either the Netherlands or Switzerland (his intended home) to determine his new, legal domicile. A month before the title match, Korchnoi had gained permission for Swiss residency, but the Soviets still objected to the use of the Swiss flag and wanted only a white flag marked “Stateless.” The Baguio 1978 jury instead decided that no flags would be allowed on the playing table, but that the flags of FIDE, the USSR and the host Philippines would reside onstage.

The Grand Yogurt Controversy . . . or the “Korchnoi’s Complaint”: This started on the 25th move of Game 2 when a waiter delivered a glass of violet-colored yogurt to Karpov at the playing table. Korchnoi’s team complained immediately and vehemently: “It is clear that a cunningly arranged distribution of edible items to one player during the game . . . could convey a kind of code message.” The organizers then decided that yogurt could be brought any time to either player provided it wasn’t violet or a shade of blueberry. Where was an Official Yogurt Sponsor when you needed one?

The Mind-Intimidation Games –Psychics and Other Paranormal Distractions: First there were the sunglasses. Like in any cerebral face-offs, chess players love to outstare their opponents, and Karpov had this reputation of being one of the best “stare-rs.” To counter that edge, the older Korchnoi wore mirrored sunglasses through most of the tournament. The younger Karpov recalled, “[The sunglasses] were like two mirrors, and whenever Korchnoi raised his head the light from the numerous lamps on the stage was (thrown back) into my eyes.”

Three chess grandmasters whose paths have crossed in this story and elsewhere:

Anatoly Karpov, the 1978 champion, in recent years. Karpov first met Torre at a Manila Zonal in 1976.

Viktor Korchnoi, the challenger, with his infamous reflective shades. Date unknown but mid-life.

The Philippines’ own Eugenio Torre, Asia’s 1st Grandmaster (1974), co-title-holder of GM having attended the most Chess Olympiads—20.

Those Wild and Crazy Russians

Like many high-stake duels, the two principals came with their own set of seconds and teams who managed the off-stage details. Karpov’s was very old-school Soviet, with its own minder, and some schooled in the KGB ways of intimidation. Korchnoi’s, already outside of the Soviet orbit, gathered an international team of supporters and believers, one of whom was Raymond Keene, an English chess grandmaster whose “The World Chess Championship—Korchnoi vs. Karpov,” provided one of the most up-close, personal and ringside-seat accounts of those championships, warts and all.

Back to the mind games. The two teams now brought out the heavy guns—the Psychics and the Paranormal. The Karpov team trotted out a Vladimir Zukhar with “eyes supposedly like burning coals,” and he was planted in the first few rows in Korchnoi’s line of sight. The New York Times’ Robert Byrne wrote: “What powers this Dracula-clone was supposed to possess never came to light, but he drove Korchnoi into a rage.” ‘Twas said that Korchnoi felt Zukhar’s thoughts entering his brain.

Team Korchnoi responded with two members of the Ananda Marga yoga cult, Steven Dwyer and Victoria Shepherd, who were free on bail, pending murder charges in the Philippines for stabbing an Indian diplomat in Manila that February. (Ananda Marga was a more malignant Hare Krishna-type sect.) The duo, nicknamed “Dada” and “Didi,” started attending the 18th game to counteract Zukhar. In the off-times, Dada and Didi also taught Korchnoi and others on his team transcendental meditation.

It then became the Soviets’ turn to panic. They asked Florencio Campomanes, the local organizer of the championships, to have the yoga couple in white garments and saffron robes, keep their distance from the Karpov team.

Really, about the only thing missing was the demonic, mesmerizing stare of Rasputin, the legendary mad monk who brought down the Russian monarchy.

If they could’ve resurrected Rasputin, the two opposing camps of the 1978 championships would probably have recruited him.

The Chairs: Not quite the absurdist Ionesco play, but almost. Korchnoi brought his own dark green Stollgiroflex chair with hydraulic lift to the tournament. Karpov's chair was furnished by the organizers although he needed a small cushion to raise him to Korchnoi's level. Karpov requested that Korchnoi's chair be examined for “extraneous objects or prohibited devices.” Before the match began, Korchnoi’s $1,300 chair was dismantled, X-rayed at Baguio General, and cleared of any high-tech entrails that the KGB did not already know about.

By Games 14 and 15, Korchnoi complained that Karpov was swiveling too much in his chair. Karpov said, "I'll stop swiveling if he takes off his glasses." The jury decided the next day that "swiveling of one's chair or standing behind it, is not to be allowed.” Karpov stopped swiveling during Korchnoi's move for Game 16. At the rematch in 1981, Korchnoi threatened Karpov, “Get off me, you detestable worm,” when he swiveled his chair. Karpov had finally found a way to get under his opponent’s skin.

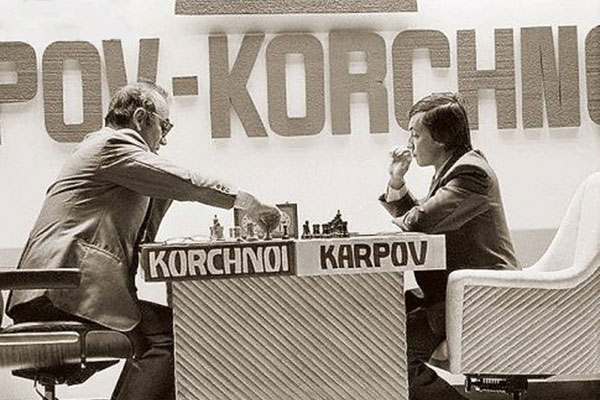

Korchnoi vs. Karpov (Source: Chess86.ru)

And so it went, for almost the 3½-month stretch of the championship, the jury and Campomanes were constantly besieged by charges and counter-charges hurled by the opposing camps.

How Baguio Was Chosen as Host

Through a combination of luck, good geo-political feng shui and sheer organizational pluck by Florencio Campomanes (or “Campo” for short, as intimates and associates called him), Baguio got the hosting honor.

Remember that after the Marcoses declared martial law in late 1972, and the global press started treating them as ruthless murderers and crass dictators, the couple went on an all-out, full-frontal “charm” offensive to neutralize this negative international image.

Following Imelda’s series of international hostings in the ‘70s: Miss Universe in 1974, Da Thrilla in Manila (the world heavyweight bout between Cassius Clay and Joe Frazier) in 1975 and the money-bleeding International Monetary Fund Conference of 1976, there was the little-noticed Chess World Championships of 1978 in Baguio. Because it was a small event and did not involve 80 or so international beauties to walk the runway, or require Imelda to turn a whole metropolis into another Potemkin village, the rather somber event was largely left to husband Marcos’ tutelage.

In-between leading “diplomatic” missions and playing footsies with proletarian leaders like Chairman and Madame Mao Tse Tung, the colorless Soviet leaders, Cuban dictator Fidel Castro, Imelda, of course, pushed her hokey, totally transparent “Star and Slave for her People” mantra, grandly hobnobbing with leading global names in the arts and rarefied fields, like pianist Van Cliburn, and even second stringers George Hamilton and Gina Lollobrigida, in the “name of her penurious people.”

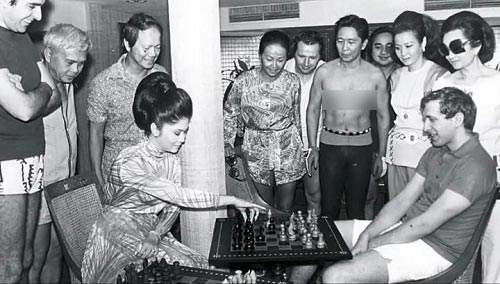

Among those luminaries was American Grandmaster Bobby Fischer who, before he was crowned world champion in 1972, had already been to Manila a number of times courtesy of Campomanes. The following picture, only recently released on the Internet, shows Imelda and Ferdinand hosting Fischer at Malacañang in 1973 at the time of the First Philippine International Chess Tournament in Manila. Marcos formally opened the event at the Araneta Coliseum.

Bobby Fischer (seated, right) playing with, to use a chess pun, the Filipina “queen” in Manila in 1973. This racy photo was found among personal photo albums Fischer had abandoned at a Pasadena storage locker when he left California for New York in the 1980s. Classified as “abandoned,” the storage facility auctioned off the personal property, which subsequently ended up in a yard sale. The new owner of the albums posted this photo on the Internet. Did Fischer gallantly let Imelda win? Marcos’ image had been redacted for propriety’s sake.

During his many visits to Manila and Asia until the turn of the century, Fischer even managed to find himself a live-in Filipina girlfriend, one Marilyn Young, and maintain some sort of long-distance relationship, given the erratic genius’ peripatetic wanderings; but more about this later.

On New Year’s Day 1975, the Philippine Chess Federation (PCF) put in a bid to host the 1975 world championship with $5 million dollars for the purse. It beat the puny bids from Mexico City (US$387,500) and Milan, Italy (US$426,250) plus costs of staging the tournament.

On the day of the FIDE announcement, the International Monetary Fund asked Philippine Secretary of Finance Cesar Virata how a debtor country like the Philippines could manage such a bid. Virata relayed this query to Marcos who called two other Department Secretaries before narrowing it down to his assistant, Guillermo de Vega, who had guaranteed the bid. “Send me a memo,” was all Marcos asked, and nothing more came of the matter.

However, the June 1975 match in Manila was not to be. Fischer, the reigning champion, would not back down from a dispute on the tournament format to be used in Manila – until he resigned in June 1974, and the title was inherited by would-be challenger, Anatoly Karpov. It was the first time in history that a new world chess champion was declared without having actually played the game (or a series of games).

Chess’ Loss, Boxing’s Gain

When that chess championship for Manila fell apart, Marcos simply moved the prize money to the next circus—Da Thrilla in Manila. In Da Thrilla (which was the highest-watched-on-TV sport event up to that time), slated for October 1, 1975, Ali was guaranteed $4.5 million against 43 percent of the gross, while Frazier was guaranteed $2 million against 22 percent. In actuality, Ali ended up with nearly $9 million and Frazier made roughly $5 million. (That purse has since been eclipsed by the bouts Manny Pacquiao has fought.)

Of course, it was easy for Marcos to “bankroll” such extravaganzas because the money wasn’t really coming out of his pocket. It was poor Juan de la Cruz who again footed the bill.

The next year, a Russian grandmaster, Viktor Korchnoi, defected to the west while playing in the Netherlands. A younger Soviet grandmaster, Anatoly Karpov, however, with KGB agents in tow, kept his commitment to play at a Zonal (i.e., regional) match in Manila, also in 1976. But Karpov was beaten by local champion, Filipino Eugene Torre. That was Karpov’s first bad after-taste of the Philippines.

In the meantime, Campo regrouped to try and secure another championship in the Philippines. As these things do not happen by themselves overnight, the country, having had first option for the aborted 1975 round, bid again for the 1978 match. The 1978 bid went up against Hamburg, Germany; Graz, Austria; and Tilberg, Holland; and this time, the PCF offered the more serene city of Baguio.

The Highest Prize Money in Chess Up to the Time

The purse was not the deciding factor – and the exorbitant amounts for 1975 were not repeated for 1978. Because there was a longer format and the host nation would have to pay for the prolonged staging of the tournament, the prize money went down to US$550,000—to be split $350,000 for the winner and $200,000 for the loser. At the time, it was the highest (actual) cash prize ever offered in chess (unlike the 1975 offer which never came to pass).

Three years later, at the 1981 rematch in Merano, Italy, the purse went down—US$260,00 for the winner; and about $160,000 for the loser. But for the Baguio 1978 match, there were rumors that loser Korchnoi did not collect his winnings because, erratic prima donnas as chess grandmasters ever are, Korchnoi refused to sign the final, official score sheet, thus forfeiting his share of the prize. Also, at the Merano 1981 rematch, the old adversaries and cohorts resolved to concentrate on play proper and forego all the showboating antics they had indulged in in the Philippines.

The Man Behind It All

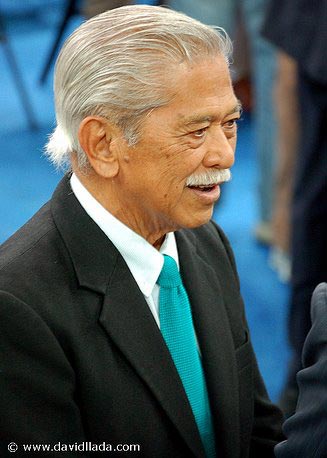

Florencio Campomanes, the Philippines’ grand old man of chess, circa 2005. (Photo by David Llada)

There was no one quite like Florencio Campomanes in promoting chess in and for the Philippines. Born in Manila on February 27, 1927, Campo was essentially a self-made man. He graduated cum laude in political science from the University of the Philippines in 1948. Not coming from a landed family, Campo qualified as one of the first Fulbright scholars—obtaining his masters at Brown University in 1951, and nearly completing doctoral studies at Georgetown 1949-1954.

Since Campo had become a habitué of the Manhattan and Marshall Chess Clubs in the 1950s, he was exposed to organized chess, and on his return to Manila he co-founded the Philippine Chess Federation in 1956 and affiliated it with FIDE.

For a while, Campo was a lecturer at UP. However, chess remained his real passion. He was National Master strength player and national champion in 1956 and 1960. He then became an International Arbiter in 1957 and was a captain/member of Philippine teams from 1956 to 1980, going to five Chess Olympiads: Moscow 1956 through Havana 1966. (The Chess Olympiads are held on even years.)

He rose through the ranks of FIDE—first as Philippine delegate, 1956 to 1982; Asian Zone President, 1960-1964; Deputy President 1974-1982; FIDE President from 1982 to 1995, Chairman in 1995-1996 and Honorary President from 1996 until his death in 2010.

Campo played ball well with the various Philippine administrations through the years. He also had chutzpah.

Confronting Imelda’s Boys

Although both were from UP, Campo and Marcos were not particularly close. Campo’s entrée to Malacañang was through Presidential Assistant Guillermo de Vega.

Longtime Campo confidante Casto Abundo, who was also his General Secretary and Executive Director at FIDE from 1987 on, recalled that in 1977, the Philippines had already committed to host the 1978 championships in Baguio. Preparations, however, were woefully behind. So Campo got himself invited to a Cabinet meeting in Malacañang to personally and urgently plead his case before Marcos.

There, he had the temerity to single out two of Imelda’s favorites on the cabinet as blocking the championship’s preparations. First was Central Bank Governor Gregorio Licaros whom Campo accused of withholding the two million dollars (around Php 20 million at the time) which had previously been promised him to pay for the tournament. (Licaros was Imelda’s in-law of sorts; her favorite niece, Margarita, was then married to a son of Licaros.)

Campo also named Tourism Minister Joe D. Aspiras for not committing the Baguio Convention Center to the tournament. Aspiras made the excuse that “The First Lady has reserved it.”

Marcos replied, “I will take care of the first lady. Give (Campo) the venue.” And with that one appearance, Campo got the funding and preparations back on track, without incurring the ire of Imelda—a common fate for those who had crossed her.

In 1982 Campo ran for and won the presidency of FIDE, achieving something no Filipino in history had ever done—heading a bona fide international sports federation, which were normally chaired by European or North American (i.e. Caucasian) men. (The fact is, because most of the federations—some 45 of them— are headquartered in Europe and most of the activities take place there, it only makes sense to name Europeans/North Americans as CEOs so the dislocation on their personal lives are minimized.)

But with the feat of winning the FIDE presidency, Campo held that rare distinction of being one of only four Filipinos, to date, to belong to a major international sports organization.

If one can recall, Carlos P. Romulo sat, in 1949, as the 4th president of the U.N. General Assembly for that Session only. On the Olympic front, Jorge B. Vargas served as a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) from 1936-1980. Second was Francisco Elizalde, 1985-2012. Michaela Cojuangco-Jaworski is the third IOC member from the Philippines presently. But Campomanes beat them all as he was the first Filipino to head a fully accredited international sports federation.

Campo’s election to the FIDE presidency in 1982 paved the way for an even bigger tournament in Manila in 1992. He brought home and organized the 30th World Chess Olympiad in the final weeks of Cory Aquino’s administration—June 7-25, 1992. They were held at the PICC, the Philippine International Convention Center.

Commemorative material from the Manila 1992 30th Chess Olympiad, left to right): official logo, the 5-peso commemorative coin (the obverse); and a medal. Note Rizal monument incorporated into the logo.

A record 102 countries participated in Manila 1992. For the first time, there was a women’s division. Instead of one USSR team, there were 12 teams from the former Soviet Union. In the men’s division, the Philippines took 31st place, with its “A” team led by Eugene Torre. (Torre led the Philippine men to its best team finish at Thessalonika 1988, coming in at 7th place!)

But Manila 1992, successful as it was, would have ill repercussions for Campo a few years later.

A KGB agent or a Russian pawn?

How did Campo survive and maneuver his career at FIDE, considering nothing major at FIDE happened without the Soviets’ approval? Was Campo a Russian pawn? Or coming from a middling Asian country, was he a compromise candidate—like U Thant when the mild-mannered Burmese diplomat was Secretary-General in the United Nations?

Campo withstood these accusations of being a KGB spy and even won reelection. He was also the first Filipino to have been accused of being “a KGB spy,” or at least while he was still alive. Campo was in good company in this dubious repute because IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch, who had served as Spain’s ambassador to the USSR until 1980, had likewise been accused; but the smear was made after Samaranch’s death.

In 2003 (during Macapagal-Arroyo’s tenure), Campo was charged by the anti-graft court, the Sandiganbayan, for supposedly failing to account for $238,745 in government funds earmarked for the Manila 1992 Olympiad. That amount was missing.

Campo, who had not accumulated any considerable wealth to speak of in his illustrious career and was already 76 at the time, denied that he ever stole public funds or accepted bribes. He fought the graft charges all the way to the Supreme Court which, in December, 2006, cleared him of any criminal liability.

In May 2010 Campo, whose legacy was not only raising FIDE membership to over 150 national federations when he was done, but also put the Philippines on the international chess map, even if sporadically, succumbed to cancer in Baguio. He was 83.

Here is one of the last interviews Campo gave:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J313A66odAI&t=7s

Fischer’s Other Filipino Connection

The other crazy angle to this whole Chess-Campomanes-Fischer saga, is that Bobby Fischer supposedly fathered a daughter, Jinky, by his Filipina live-in partner, Marilyn Young. Mother and daughter laid claim to Fischer’s estate when he died in Iceland in 2008. When the estate was settled in 2009, however, a DNA test confirmed that Jinky Young was not Fischer’s daughter.

Bobby Fischer estate claimants Marilyn Young and her supposed daughter by Fischer, Jinky, visiting the grandmaster’s grave in Iceland in November, 2009. Their claim did not survive a legal challenge.

Finally, as if the traditional, two-dimension flat-board chess isn’t difficult enough for the average person to play, someone had to come up with this:

Est-ce votre jeu, o petit prince? (Is this your game, oh, Little Prince?)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fSWLSskBLWo

Will there be a Filipino Grandmaster/Mistress who can tackle this devious version?

References:

http://www.rappler.com/sports/by-sport/other-sports/137059-1978-karpov-korchnoi-chess-championship

“The World Chess Championship – Korchnoi v. Karpov,” Raymond Keene, Simon & Schuster, New York, ©1978

https://en.chessbase.com/post/florencio-campomanes-turns-eighty

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/06/world/asia/06campomanes.html

http://chessheroes.blogspot.com/2009/06/remembering-1992-manila-chess-olympiad.html

http://theweekinchess.com/chessnews/obituaries/florencio-campomanes-1927-2010

http://www.thechessdrum.net/blog/2010/05/03/florencio-campomanes-dies-at-83/

http://en.chessbase.com/post/marilyn-and-jinky-visit-fischer-s-tomb

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. Myles has authored two books: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies, and Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes published in 2016. He is also a contributor to the Journal of the ISOH (International Society of Olympic Historians) where he has had two articles published.

Myles’ first stage play, “23 Renoirs, 12 Picassos, . . . one Domenica”, was recently given its first successful fully Staged Reading by the Playwright Center of San Francisco. “23 Renoirs” . . .” is the little-known story of one Domenica Guillaume-Walter of Paris, and how she ruthlessly schemed to keep her family’s art collection intact for herself, even completely cutting off her own son. The play is now available for professional production, and hopefully, a world premiere in the SF Bay Area stages.

Finally, Myles’ third book, “Of Adobe, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles – An Anthology of Essays on the Filipino-American Experience and A Little More” will be released in October 2017—in time for the 4th (2017) Filipino-American International Book Festival on October 5, 6, 7. 2017, happening in San Francisco. His newest book will feature most of his articles published here on Positively Filipino and some other, eclectic, personal-favorite material of his. For enquiries on any of the above: razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia