The Secret Post-9/11 Pinoy-‘Gitmo’ Connection

/The most infamous of these islands are Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay, the even more dreaded Devil’s Island, Robben Island prison off CapeTown and the supposedly “escape-proof” Chateau d’If where, as the French say, les mecs vraiment vraiment mauvais (where the really, really bad dudes) were kept. These fortresses were most likely built with forced or penal labor.

How strange it is that the Philippines, with more islands to spare than anyone else, never had any penitentiary-only-dedicated islands of its own. It has always been Fort Santiago, Bilibid or Camp Crame. Even in the Spanish era, national hero Jose Rizal wasn’t sent to some water-enveloped exile; it was just to Dapitan, a town on the northern Zamboanga coast. Okay, the Culion leper colony in Palawan and Isla de Convalecencia (Convalescent Island) on the Pasig River might qualify, but they were established for health, not penal purposes. The former in Palawan is no longer an active leper colony, while Isla de Convalecencia (the original Hospicio de San Jose) still functions as a small haven for restoration and healing right in the heart of clangorous Manila.

And so we come to “Gitmo,” short/military slang for Guantánamo Bay, the infamous US naval base in Cuba. Filipinos are no strangers to overseas US bases. For post-WWII decades in the previous century, the Philippines was host to two of the most active foreign US bases: Clark Air Force base in Pampanga and Subic Naval base in Olongapo City, Zambales. This brings us to the notorious “brig” facilities at Guantánamo and its little-publicized Filipino connection.

The sweat of some two hundred, nameless Filipino workers went into the creation of what has turned out to be this century’s version of Devil’s Island. The short but true story of how some Filipinos quietly and inadvertently helped “turn” the backwater naval base into an infamous stockade can now be told. For reasons you will discern, this backstory was not “well-publicized” and was, in fact, often only spoken of in whispers.

Due to the decades-long relationship between the US and the Philippines, many Filipinos served in key, confidential positions on the staffs of US generals like Eisenhower and Douglas McArthur. (Even the contemporary story of Dr. Cristeta Comerford comes to mind http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/her-lolas-legacy-chef-cris-comerfords-secret-sauce; she’s the Executive Chef in charge of feeding recent US presidents and their families.) Many other less celebrated Filipinos have devoted long careers as civilian employees of US bases in the Philippines. When those facilities closed, not a few opted for re-assignment to US bases elsewhere, even in foreign settings. Enter Gitmo.

A Brief History of Guantánamo

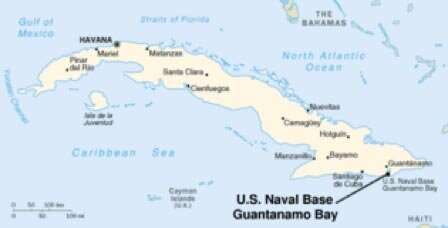

Guantánamo Naval Base is at Cuba’s southeastern-most corner

The famous song Guantánamera is indeed about that part of Cuba. It sings of a guajira (country maiden) from Guantánamo Bay. I wonder if they play the song on the base’s PA system?

A more detailed map showing the actual parcel of Guantánamo Naval base controlled by the US. The whole area, including the Bay, comprises 116 sq.km (45 sqm). It is the only American military base located in an unfriendly country.

In the Spanish-American war of 1898, while American admiral George Dewey was confronting the Far East Spanish navy in Manila Bay, a contingent of US Marines together with Cuban allies made a beachhead in Guantánamo Bay in their bid to oust Spanish forces from the country. The Americans eventually held on to Guantánamo Bay and its primitive facilities as a coaling station and naval base and never let go. That makes Guantánamo the oldest American military base in a non-US territory.

When Cuba became independent in 1901, the 45-sqm. or 19,621-hectare bay island was leased in 1903 to Cuba’s new and bigger protector/friend. In exchange for minimal fees ($2,000 in gold per year from 1901; adjusted to $3,386.25, based on the price of gold in 1934 at the time), the US “extended” its North American footprint. Because the base provided lots of jobs for locals in the depressed Oriente province, Cuba allowed the base to stay, even during the Castro years.

When Castro came to power in 1959, the first rent check was supposedly cashed by “mistake” (which meant that they recognized the lease as valid and binding); but not ever since. Although the rent was adjusted to $4,085 /per year in 1974, which it is today, Havana has never cashed the succeeding rent checks (to signify that it does not recognize the 1903 arrangement). Gitmo continues to be used rent-free by the US. Because no expiration date was set in the 1903 lease and US withdrawal would have to be based on a mutual decision, the superpower has continued to stay in Guantánamo until it sees fit otherwise.

In October 1962, World War III almost came to pass with the nuclear showdown between the US and Soviet-allied Cuba. President John F. Kennedy launched a naval embargo to stop more shipments of Soviet missile parts to the country, with Gitmo playing a role. Moscow and Havana backed down in the face-off. In the years after, Gitmo was used as a major refugee-staging station. Due to a coup d’etat in Haiti in 1991, thousands of Haitians who fled by sea for Florida, were diverted to Gitmo temporarily. Then came the marielitos wave when 30,000 Cubans who tried to reach US shores were intercepted at sea and returned to hastily to makeshift camps in Guantánamo for proper processing.

Then September 11, 2001 happened, and the base’s utility for the US changed drastically. The Bush II administration and the Pentagon decided that Guantánamo would be the ideal place to detain terrorist suspects.

Why Guantánamo?

Guantánamo is very unique. It is a no-man’s-land in legal terms because it is not on sovereign US territory but is merely on perpetual “lease” from a nation whose human rights record is highly questionable. Thus, the US felt it could obscure its commitment to the Geneva Convention and international law for detention of civilians by holding terrorism suspects on the base. The US argues that since the exclave has always been a military base there can be no precedence of civilian law. Military laws would always prevail, and holding “stateless” prisoners as terrorists there indefinitely is completely valid and legal.

While the US Department of Defense (DOD) was drawing up stockade plans and the rest of the US was getting distracted by the glorious XIXth Winter Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, Utah, the Pentagon in February 2002, went about a crash-but-very-quiet-labor-recruitment-operation in Manila. With Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in power at the time, international American engineering firm Brown & Root, the Pentagon subcontractor assigned to this particular project, teamed up with the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) to recruit skilled construction workers for a quick, unspecified job “somewhere in another hemisphere.”

The front gate of the stockade which the incognito Filipino workers built would eventually and formally be called “Camp Delta.”

That much, insofar as official Filipino involvement, is known. Many other details aren’t, and the following is conjecture on my part, but the reader will see that the dots connect.

POEA probably contacted, discreetly, top Filipino construction firms like DM Consunji, A.M. Oreta, AG&P, etc., perhaps even the US Embassy’s old contacts in Clark and Subic, to find qualified carpenters, welders and fabricators in a matter of weeks who were:

- honest, industrious, healthy;

- had previous, trouble-free work experience at Clark or Subic;

- could be counted on for discretion; and

- could get away on short notice from personal commitments for two to three weeks.

Why Filipinos?

As noted before, there is longstanding trust between the US and its one-time colony, which did not develop with Cuba or Puerto Rico. Perhaps Filipinos are still more subservient than Puerto Ricans and/or expat Cubans (especially if you wag the almighty US dollar sign before us?).

Filipino construction crews are used to a humid, tropical climate. Having them work in a similar condition, in a March timeframe, would cause very little adjustment or down-time. But perhaps most importantly, by the time the workers realized what their project was, they would shortly be back in the Philippines.

Certainly, one unspoken hiring requirement was Muslim workers need not apply, to avoid complications should workers realize they were building a high-security pen for mainly Muslim radicals). So, the chosen workers were most likely Christian men from Luzon.

Who else could the US have hired? It could have hired Jamaicans, Haitians or Puerto Ricans, from the three closest islands. But there really isn’t a deep history with Jamaica and Haiti. If the US had hired Puerto Ricans, it might as well have hired Americans from the mainland. But the main point was to hire relatively discreet, unknown persons who would not have been squeamish about the job. And after the wraps were off, these workers – say, a carpenter or mason from Laguna or Cavite -- would be hard to track down halfway around the world by the ACLU or the nosey western press.

OK, not quite storage lockers, but it is a prison. What else?

In all, 199 Filipino workers were recruited and were most certainly asked to sign NDAs (Non-Disclosure Agreements). They were to be adequately compensated in US dollars. While no figures have become available, my guestimate is that for the projected two-week “work period,” the basic laborers would have been promised at least $2,600; foremen and supervisors a little more; and small bonuses if the work was accomplished early.

Since they were foreign workers, the sums were probably tax-free, and converted to 2002 pesos, a worker would’ve netted at least Php 260,000. That sum wasn’t bad for the 12-14 working days, and with board, lodging and transport all pre-paid. Throw in full access to the PX for good measure, the recruits would’ve been nothing but happy campers. I also imagine that a few cooks were in that lucky “199” to prepare Filipino-type meals for the men.

Secret Charter Flights

It was all going to be a very strict, hush-hush, “work-only” junket. No side trips to Vegas, or even stopovers at civilian airport shops or outlet malls. Reminiscent of the “probably infected” US nationals returning from China on Kalitta Air flights now happening, the US-DOD signed up a DC-10 from Elektra Airlines (a Greek-registered charter airline) to bring the chosen 199 Filipino crew to Cuba.

From Manila, they were flown westward the long way around, rather than through the Pacific and over Mexico. There were refueling stops at US bases in Dubai, Greece and Portugal; then across the Atlantic, directly to Guantánamo. Because of the urgency and “limited” nature of the trip, there probably was no need to secure regular Philippine passports for those who didn’t have any, after all it was going to be a strictly a one-stop journey and Guantánamo is a legal “no-man’s land.” And even if passports were used, no visas were probably issued for the workers to keep as souvenirs. All that would’ve just created a paper trail for inquiring minds.

I imagine the actual construction plans were drawn up by the US Marine Corps and Brown & Root. Materials would have all been pre-ordered and ready for use the moment the Filipino workers arrived. Because most of the recruits were aboveground workers (i.e., not into building foundations and piping), digging for foundation and light plumbing was already done by contracted excavators and hoes.

Because it was a highly classified, secret mission—and this was before the versatile smartphones we now have existed—no photographs of the work are available. But once the project was completed, the journey back to Manila by 200 well-paid workers would most probably have been just as quick and quiet as the outbound journey.

Where the bad dudes are kept. Note the seemingly flimsy structure of the “pens” built by Filipino crews. At least the detainees can face Mecca to pray.

A Political Flashpoint

In the years since, Guantanamo has become a political flashpoint in American politics. After George W. Bush left office, Barack Obama pledged to shut down the base. He did not; and his successor, Trump, took an even more hawk-like stance in keeping it in use for the purpose it was originally built for.

So, did the Philippines pimp out 200 of its sons for a very “imperialistic job” by its former overseer? Or did the Philippines do its share in the global fight against terrorism, considering it has not been immune to terrorist attacks by jihadists (remember the “Bojinka Plot” uncovered in Manila in 1995?) Filipino nationalists (and those with no love for the USA), I am sure will blanch at this story. But it is now history.

If anything, the episode attests to the trust and mutual respect between two allies who have been through thick and thin. Uncle Sam could very well have gone elsewhere and hired others, but who could they trust? In the process, the project at least brought small bounties for some 200 “lucky” Filipino blue-collar workers.

I imagine that some of the workers have already told their children and grandchildren that 18 years ago, some “200” ordinary Filipino construction laborers were flown halfway around the world to a very remote palm-dotted site that looked not unlike the Philippines. There, they quickly built forbidding pens and cages whose intended inhabitants they did not know.

Or did they?

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. He has written three books: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2016); Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes (© 2016); and his latest, Of Adobe, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles—all available in paperback from amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, UK and Europe).

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH), contributing to their Journal, and pursuing dramatic writing lately. For any enquiries: razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia