‘The Month of December, 1872’ Dr. José Rizal’s Rough Draft

/José Rizal: Political and Historical Writings (Source: www.heritageartcenter.com)

This piece had remained in perfect limbo, hidden in plain sight for three reasons. First, it is not a political treatise, as most Rizal manuscripts are wont to be, and was therefore kept below the radar. Second, it was called a rough draft and thus it remained in the eyes of publishers as work unfinished or in progress. Finally, it was misidentified in a volume classified as political and historical.

In this article, Rizal never fails to give friars a left-handed slap in the face and gleefully makes shrimp paste (bagoong or dried fermented shrimp characterized by its heady smell) of their pleasure-filled Catholic mission of presiding at the confessional.

A master of the satire, Rizal was still mulling over the seed that will become his widely read Noli Me Tángere (1891).

Noli Me Tangere (Source: Vibal Foundation)

Here we give you verbatim Rizal’s little strophe.

“To a traveler in the month of December 1872 Manila would be always the same: to a Manilan it offered numerous and very new hues.

The most Catholic country according to the revered friars, the first and last inhabitants of the Philippines--continue, it is true, to be ever so Catholic, but it has undergone notable changes in morality. It is still called--and it will be called for a long time--the meek flock of the Church, the most suitable epithet that always reminds one of the poetic idea of goats, bucks and sheep nibbling grass while the shepherds play the flute, stretched on the grass under the shadow of leafy trees.

It seems the same country with its pre-Christmas Masses, with its music and orchestras, with its dinners and banquets, but to one who knew it two years before it is undoubtedly not the same. He will suffer what the Chinese shopkeeper does to an unwary provincial shopper, showing and selling him some piece of good cloth and then giving him entirely another, similar but altogether different. And in fact the pre-Christmas Masses are no longer so neither animated nor so well attended. The musicians are no longer so numerous and if they play at all, it is for pay, or as a duty, and the dinners are very dry affairs and with little spontaneous gaiety.

The Manila people, as if depressed by a sad recollection, by an inner mourning, receive their guests with a smile indeed, but what a smile! Like the way a hospital woman whose children had died in an epidemic would receive travelers with sadness, with misgiving, but with resignation.

Their thoughts are divined, they hide their sentiment, and the walls of the confessional do not get wet with sweat and tears. The memories of January and February drive away the most sanctimonious from those courts of justice--of penitence. And nevertheless 1872 has been a great year for the Philippines!

A rio revuelto ganancia de pescadores.” (In troubled waters, fishermen catch fish.) The fishermen does not pay attention to the river nor to the fish, which is the only loser for the moment at least.

The omnipotent persons, those with value and virtue, that is, the reverend friars, the military, the governor general: The first won souls for heaven; the others, crosses and the last, eternal renown as savior of the mother country. It is evident to us that they boast officially of rectitude, justice and magnanimity.

The governor general was a great politician and modest. Having failed to win laurels in Europe, he wanted the Philippines to offer him wreaths, a truly difficult enterprise there where the evergreen oak and laurel do not abound. He had to content himself with banana leaves, which did not impede that the merit be great and the work immense. A colonel, excited by the memory of eminent deeds and not wanting to remain behind, nor to die in obscurity without winning fame, struck with his saber right and left a crowd attending the most moral and edifying spectacles, in the very place where the illustrious religious fulfilled with pleasure their Christian mission—it is always pleasant to comply with one’s duty—wishing their fellowmen a holy and good death that Heaven concedes always to the enemies of religion. An unheard of charity is to wish well even those who have done us evil!

Earning no little fame with them was Adobo, the popular Adobo, a parrot by dress and divine by his functions, minister of men and of God of Vengeance. Though he ought to receive more pesos than blessings at least from the people—that people which always have a tear for the unfortunate, a blessing for the noble deed, and many goods for the ambitious aspirations of the powerful.

Strange and curious anecdotes circulated in a low tone among the populace. A story is told of an old poor man, deaf like a bonze, who is saluted but whose hand is not kissed, as he goes home at nightfall. All that time it was very dangerous to walk through the streets and above all in groups of more than one person. A soldier sees a bundle stir, a shadow approach slowly and carefully. He cries “Quien vive?” (Who is there?), and trembling with emotion, a mite shadow advances. With the vision before his eyes of a consecration, galloons, a pension of three pesos he aims and fires. The mother country has been saved! Long live the mother country! They approach carefully to examine the terrible disturber and they see a poor old man rolling on the ground vomiting blood.

From this deduce that in countries like the Philippines, without doubt on account of climatological conditions, deafness is a predisposing cause of violent death.

Thus began this year and as it began well, it ought to end in the same manner. The King of Cambodia Shri Norodom I with various princes of royal blood visited the Philippines. He came attracted by the desire to know the heroes, lost in those solitudes. There were reviews, parades, promenades, feasts, etc. The chivalrous governor placed the royal guests at his left, giving a patent of hospitality as well as of arrogance. In much later times another governor, a competitor for glory made the Jolo ambassadors dance at his palace the war dance that they call moro-moro.

Public tranquility was now and then disturbed by the vulgar and little varied news that late at night was searched the house of Mr. So and So, a subscriber to European periodicals and therefore wicked and impious.

I remember that three years afterwards—I was still a child—I lived in the house of a good man whom they called the University Doctor of Morals, very religious, incapable of incurring the hatred of a friar. The gentleman was terribly horrified when he saw in my hands a piece of newspaper that looked European. He made the Sign of the Cross and jumped, though he walked like a turtle, he snatched the paper from my hand, and that day he was not able to eat well.

There were four or five names that could not be uttered in public and a picture that could not be shown to anybody with impunity. Nevertheless all kept the name in their memories and in their hearts, and the picture was kept in the sanctuary of the home. The people regarded certain individuals with rancor for being the cause of so many evils, and they asked if there was justice.

The whole country was disarmed. Not even a poor rifle remained in the houses to defend properties from bandits or thieves who infested the countryside, like a bearded bandit whom they called Castila, bloodthirsty and ferocious, irreconcilable enemy of the government rather than of the private citizens, who seemed to have escaped from the theater of events of January.

The news received from the distant and unwholesome islands of the exiles were the most disheartening and sad. The families who had courage and resignation received them in public, silent and taciturn but in the quietness of their home, they shed abundant tears. The more pusillanimous went to the palaces bringing gift and money in order to see if thereby they could get the freedom of their parents or brothers. Not lacking also was a loving wife, who desirous of living chastely accused her husband of being a filibuster. If he was rich, he was immediately arrested, leaving a wife free and alone; if he was poor, they paid no attention to him and the most that they did was to send him to exile without bothering him with trial. Sometimes it was a father who had a pretty daughter. The town parish priest, young and with sanguine temperament, saw in him an obstacle to the happiness of the girl where he forbade to frequent the sacraments, especially the most helpful of all, the confessional, and then the good shepherd sent that sheep to his exile from which he would probably not come back.

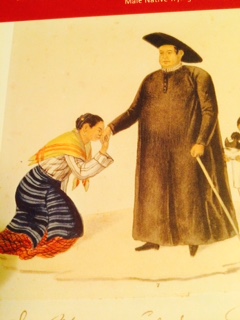

Rizal disapproved of the Friars influence on the young. The Mano po tradition was introduced by the Friars. (Source: Jose Maria A. Carino, Sonia Pinto Ner. Album: Islas Filipinas1663-1888, p. 181. 2004. Manila: Ars Mundi Philippinae)

The Philippines was governed thus.

One’s desire now is to lift the veil that covers this corpse whose shape we had seen vaguely outlined through these words, so that by their aspect we may see the emptiness of human vanities and impostures. If there is some philosopher among my readers who wishes to penetrate the mystery enclosed in the corpse, we shall make the autopsy and we shall ask the matter all its past. He who has valor and wishes to know the truth of things may follow us in our analysis. He who wants to live in peace on pain of not knowing in what environment he lives may close the book and content himself with bending his body, bowing his head, and waling with circumspection. When, after long hot days, the atmosphere is loaded with electricity and the clouds threaten to break up in frightful crashes, it is very dangerous to ignore meteorological laws and place oneself in a high place that attracts lightning. There death can be said to be certain.”

This article was written in Spanish by a very young Rizal. At the time, assuming he wrote it in 1872, he was then an “externe” at Ateneo. That year, Burgos, Gomez and Zamora were executed by garrote in Bagumbayan. Encarnacion Alzona was the translator for the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, which published Rizal’s writings in 2012 as a commemoration of the 150th Rizal anniversary celebration.

Dr. Penelope V. Flores is Professor Emeritus at San Francisco State University.

More articles from Penelope V. Flores