The Manila Boy Who Would Be King

/Before the internet, I did not realize that the young actor who played Boy King in the film was actually a young Filipino from my section of the woods, Manila. In the following clip from the film, which shows the princes and princesses of the royal Siamese court being presented to Mrs. Anna, their new English teacher, notice the Crown Prince swagger in at the 1:34 mark.

That imperious Crown Prince is Patrick Adiarte who was 12 years old at the time. Earlier this year, some 65 years after the sumptuous film version had its U.S. and world premiere on June 28, 1956, I managed to track down Adiarte.

Flash back to 1949, Manila and the new Republic were just getting back on their feet after a punishing war and occupation. Adiarte’s father has been killed in the liberation of Manila; his widow leaves for the U.S. with the six-year-old Patrick and his sister. They head straight for the bright lights of New York City to seek their fortune there. A few short years later, the young Patrick wins the landmark role, which many an aspiring child-actor would give their eye-teeth for, and some 30 years before another unknown Manila actor, Lea Salonga, would make even more global headlines in 1988 by winning the coveted role of Kim in Miss Saigon, becoming an overnight star in London.

For those not familiar with The King and I, it tells, in the best song and dance tradition of a Broadway musical, the essentially true tale of the employment of an English widow to the court of Siam in the late 1850s to teach English. The exotic tale is told against the background of the conflicted, rocky relationship between the headstrong schoolteacher and her seemingly barbaric but equally autocratic employer, King Mongkut (Rama IV) of Siam.

It’s a story that’s been told in three books (two by the real protagonist, Anna Leonowens, and the novel, Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon, on which the R&H musical is based). The King was initiated on Broadway in 1951 by a newcomer, Yul Brynner, who would later own the role as well as his trademark bald look and exotic ferocity. There have been at least four film versions, including an all-animated version (1999) of the musical with far-out alterations to the original plot line, including making the Crown Prince (Adiarte’s role) a kick-boxing champion, which seemed natural since kick-boxing is an indigenous Thai/Siamese martial sport. There was also a brief TV series in 1972 also starring Brynner but minus the rich R&H score.

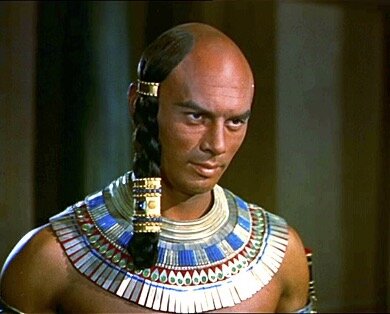

Yul Brynner as the pharaoh Rameses II in his first film, The Ten Commandments (1956) which was filmed back-to-back with The King and I.

This piece is very much about Adiarte as it is about Yul Brynner who was central to the arc of Adiarte’s story. Without Brynner, there might have been no Patrick Adiarte in show biz. Brynner’s roots too, of course, were from the Far East, although much farther north, in Vladivostok, Russia.

When Brynner burst onto the international scene in 1956 with a whole spate of films (The King and I, The Ten Commandments, Anastasia, The Brothers Karamazov, The Buccaneer, etc., one after another), a young teen-age cousin of mine, a prim and proper Manila colegiala, was all agog and smitten by the bald actor, finding him “devastatingly sexy,”as did millions of women all over the world. I seem to recall my cousin even sent away for a “signed” photograph of Brynner then. But what did I know about teen-age girls’ hormones in those days?

Banned in Bangkok

For all of The King and I’s success as a musical theatre classic in the West, it has one blind spot in its provenance. The original novel and all its iterations are banned in the locale of its setting, Thailand, because of the rather inaccurate and unflattering portrayal of the Siamese king. He was a gentle and scholarly man, not the scowling, semi-barbarian so eager to impress westerners that the dramatists made him out to be. Of course, the musical is an entertainment and obviously told from the visiting English schoolmistress’ point of view. Mrs. Leonowens’ two accounts of her true experiences at the Siamese court are also known to be rife with exaggerations and literary liberties.

While Oscar Hammerstein’s original scenario for the musical is more heavily based on the 1946 screen version with Rex Harrison and Irene Dunn than on Leonowens’ books, R&H supposedly reached out to the Thai Embassy in Washington, DC, in 1950 before commencing work on their musical version. They hoped to get some matters which did not seem culturally right in the 1946 film more correct for their new play. But the embassy supposedly rebuffed them, turning down the pair of seasoned Broadway writers, cold. So, R&H just went ahead and wrote the story of 1850s royal Siam as best they knew how. When the show finally opened on Broadway in 1951, it was a tremendous box office and critical success, and while the resulting product still did not please the Thais, one could not blame R&H entirely for not fashioning a more p.c. version acceptable to the contemporary Thais.

Patrick Adiarte, 12 when he played opposite the original king (Yul Brynner) in the 1956 film version of The King and I. Adiarte played Crown Prince Chulalongkorn, great-great-grandfather of the current Rama X. (courtesy of 20th Century-Fox)

How did the 12-year-old Patrick Adiarte land the plum film role?

Rising Through the Ranks

For a first-time film role in new Cinemascope 55, with color by de Luxe, and a $5 million budget, Adiarte couldn’t have gotten any luckier and splashier. Like most breaks in life, it was being at the right place at the right time.

Adiarte, however, had “paid his dues.” After arriving in New York in 1949, Mrs. Adiarte (somewhat like the widow-heroine of the story, Mrs. Anna, in a brand-new land) did what she had to do in order to put food on their table. Being in the theatrical center of the West, Mrs. A took her children to Broadway auditions in hope of landing them roles and making some lucre. One of those auditions was an open call for the royal children of the hit musical, The King and I. Because children grow so fast and the show was a hit, there was a constant need for Asian-looking child actors to play the royal children.

Patrick was first cast as one of the nameless, other princes. When the show was winding down, Mrs. Adiarte jumped at the chance to earn more money by signing her son up for the show’s first national tour (March 1954-August 1955). Generally, actors earn more money on the road than on Broadway because the Equity-per diem tour rates pay more than the stationary gigs in New York. On tour, Mrs. Adiarte was also drafted as one of the King’s wives while Patrick steadily rose through the “royal” children’s ranks and eventually grew into the Crown Prince’s role.

When Adiarte was finally promoted to the Crown Prince Chulalongkorn role, on that 1954 tour, he recalls developing a closer relationship with Yul Brynner. Previous to landing the King role, Brynner, with acrobatic and circus training in Europe, worked as a director in the rising, new medium of live television.

The surrogate “father-son” relationship Adiarte had with Brynner on the tour came about because as the oldest and lead minor of the company, Adiarte was tutored, off-stage, separately from his other “royal siblings” but together with Brynner’s son, “Rock.” Even though four years younger than Adiarte, Rock (who was not in the show), was placed in the more advanced educational level as Adiarte (as well as the young actor playing Louis, Mrs. Anna’s son). This serendipitous tutoring situation created a special kinship between the young Filipino actor and his stage “father,” Brynner.

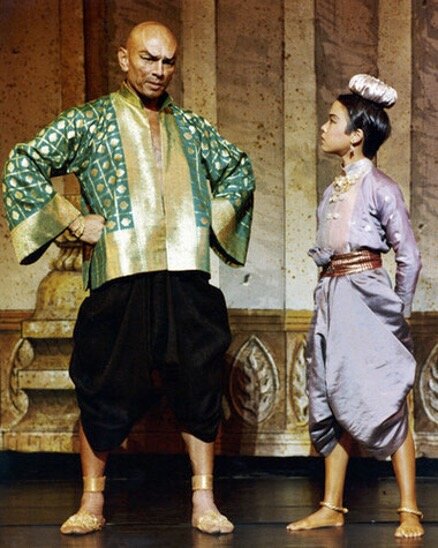

A rare photo which Adiarte himself with his “surrogate” father on stage, was unaware of, until shown to him.

Of that time spent with Brynner, both on tour and in Hollywood, Adiarte considered Brynner a “surrogate” father to him—filling a void left by Adiarte’s deceased real father.

The relationship with Brynner was interrupted in late 1954 when Brynner had to leave The King and I company to play another monarch, the pharaoh Ramses, in Cecil B. de Mille’s even more spectacular re-make of the The Ten Commandments. Brynner left for The Ten Commandments’ location filming in Egypt. A year later, Brynner and Adiarte were reunited in Hollywood when it came time to film The King and I in November 1955. By then, Adiarte, 12 going on 13, was perfectly placed to play the celluloid Chulalongkorn, just as his voice started to crack.

Brynner certainly had a hand in Adiarte landing the Crown Prince role in the film just as he had been instrumental in getting Deborah Kerr, a non-singing actress whose star was also rising, to play Mrs. Anna. It’s called the perks of “star power.”

In the final scene of the film, the Crown Prince (Adiarte) starts to take the reins of power while his father, the King, dies off on the side. (c/o 20th Century-Fox)

Of course, landing the same Crown Prince role in the film was Adiarte’s monumental break into the ultra-competitive world of show business in the USA.

(In later years, other Filipino and Fil-American artists would have their own stab at other roles in The King and I in major revivals: Lou Diamond Philips played the king in a 1996 revival on Broadway; Lea Salonga sang the role of Tuptim with Ben Kingsley as the King and Julie Andrews as Mrs. Anna on a special studio recording of the score in 1995. In the recent celebrated revival in Lincoln Center in 2015, Jose Llana who had also played Lun Tha in previous stagings, got promoted to His Kingship when the original “King,” Ken Watanabe, went on vacation. )

After the Royal Thai Reign . . .

After The King and I stint, and leaving his childhood behind with a little money in the bank, Adiarte and his family returned to New York. Nearing puberty, Adiarte nevertheless sought to stay in show business and continued with classes at the Professional Children’s School where he remembers a young Liza Minnelli and Marvin Hamlisch (composer) among his classmates.

It was also around this time that the Adiartes crossed paths with two prominent Irish-American blokes. The first was the late President John F. Kennedy (although he was a Senator at the time); Adiarte recalls Sen. Kennedy’s office helping his family secure their U.S. residency papers.

Flower Drum Song Days

In 1958, Rodgers and Hammerstein came a-calling again. They were writing another Asian-themed show, Flower Drum Song, based on C.Y. Lee’s novel of the same name. It’s the story of acculturation, the ebbs and flows of assimilation, the conflicts of Chinese Americans, set in San Francisco’s Chinatown. There was a suitable role for Adiarte again—that of the totally Americanized teenage, second son, Wang San. This time, Adiarte would be in it from the birth of the show on Broadway.

(Other Filipinos in the original 1958 Broadway cast were Cely Carillo and Maureen Tiongco as understudies and replacing Miyoshi Umeki who played the original heroine, Mei Li. Adiarte remembers Carillo and Tiongco quite well. Tiongco would recreate the Mei Li role in Manila in a series of charity performances in 1966, which raised seed money for the Cultural Center early in Imelda Marcos’ days as first lady. In the 2004 “revisical,” with the story updated and stereo-typical Asiatic tropes shaved from the story, Lea Salonga and Jose Llanas claimed that version as their own. However, it was not a great success, running only 169 performances vs. 600 for the original 1958 show.)

In Flower Drum, Adiarte worked with Hollywood hoofer Gene Kelly who directed the show on Broadway. Adiarte also recalls an association with Kelly, which went past their time together in Flower Drum. Kelly, it seems, helped Adiarte with some other show business jobs even though Kelly did not go on to direct FDS on screen. He credits Kelly with getting him a job dancing on Italian television for about a year.

Here is a video clip of Adiarte dancing with Kelly and made when Flower Drum Song had just opened on Broadway in December 1958.

When Flower Drum went Hollywood in 1961, Umeki, Adiarte, and Juanita Hall were the Broadway hold-overs. (Jack Soo. who had played the nightclub emcee on Broadway, got promoted to second male lead, Sammy Fong, for the film. Nancy Kwan and James Shigeta were the Hollywood names added to headline the film.)

In a scene from the Flower Drum Song film, Adiarte (as Wan San), hams it up with two of his friends in “The Other Generation.” (c/o Universal-International)

In his role as the very hip, wise-cracking Number Two son Wang San, Adiarte got to sing and dance more than in the K&I. In the sanitized and more revised version of 2004, however, one can blame Fil-Am playwright David Henry Hwang for entirely eliminating the Wang San role Adiarte had originated.

The Three Lives of FLOWER DRUM SONG:

Left, on Broadway, 1958; as a Hollywood film

Center, 1961 - in which Adiarte played the same role in both incarnations

The 2004 FDS update by Fil-Am David Henry Hwang

Because he had a New York background and more or less steady work growing up, Adiarte weathered that tricky transition from child actor to adult quite well. Later on, Adiarte appeared in two seasons of the hit TV series, M*A*S*H. He played the role of Ho Jon, a young Korean orphan who eventually gets “adopted” by the American G.I.s in Korea. He also got steady jobs playing guest-roles in other American TV shows: Ironside (1970), Bonanza (as Native American Swift Eagle, 1971), The Brady Branch (1972), the original Hawaii Five-O (1972) and Kojak (1974).

4x a Prince

Adiarte captured princely lightning in a bottle four times. First, not only did he make his Hollywood debut in The King and ,I but he also continued playing, most significantly, a prince of “color,” for three more times on American TV and film. After Prince Chulalongkorn, there were

• The young prince in a special TV version of The Enchanted Nutcracker with Robert Goulet and Carol Lawrence (original Maria of West Side Story), 1961.

• As Middle Eastern Prince Ammud in John Goldfarb, Please Come Home—again for his first studio, 20th Century-Fox, 1965—a madcap (mostly unfunny) comedy by William Peter (“Exorcist”) Blatty, with Shirley MacLaine and Peter Ustinov; and

• In 1968, still another turn as crown prince in an episode of the TV series, It Takes A Thief, with Robert Wagner.

John Goldfarb, Please Come Home (courtesy of 20th Century-Fox)

With Wayne Rogers in the TV series, M*A*S*H

Adiarte was once married to actress Loni Ackerman (1985-92). Until Covid reared its ugly head in early 2020, Adiarte was teaching tap dance at Santa Monica College. But when California had to go into lockdown in March 2020, Adiarte was forced into retirement. Today, 78, he still lives in Southern California.

Pinoy Casting Paradox

In thinking of Adiarte, Lea Salonga and a few other Filipino or part-Filipino actors who have broken through the “ceramic casting ceiling,” it is a curious paradox that they made their international mark not playing Filipino roles but other Asian nationalities: Thai, Vietnamese, Chinese. There is such a dearth of “true-Filipino” roles in international stories. Even Salonga has played all the major Asian ethnicities except Korean, Indonesian, and Filipina.

Perhaps the only example that comes close to being true “Filipino” casting in a major TV mini-series (2018) but in a very negative way is Darren Criss portraying Fil-Am serial killer and murderer of Gianni Versace, one Andrew Cunanan—except Criss looks more “black Irish” than Pinoy. The most prominent actor to play Imelda Marcos in off-Broadway’s Here Lies Love was Korean-American stage actress, Ruthie Ann Miles. Even Puerto Rican Rita Moreno, who played the Burmese slave girl Tuptim alongside Adiarte in The King and I film, has played a Filipina, as a female convict in the 1962 film, Samar, which she was shooting in the Philippines when she had to quickly fly back to Hollywood to claim the 1961 Oscar award for (the first) West Side Story.

All that then begs the question: when will a contemporary Filipino actor play a true Filipino in an international vehicle for the first time? The recent General Antonio Luna and Manuel L. Quezon roles don’t count because those were Filipino-financed and made films.

All these years, Adiarte has never returned to Manila. Once, in the late 1970s or early 1980s, he considered going, but the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos deterred him.

New Screen Version of “The King and I”

When I mentioned that still a new, updated screen version of The King and I was in the offing (with supposed p.c. tweaks/updates on the “misogynistic” characterization of the King), one could almost hear Adiarte’s jaw drop and mouth my exact sentiments: one shouldn’t tamper with the classics. But of course, it would have to pass the final approval of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization (RHO), the guardian “angel” of all things R&H. No further word yet on who, what, when the new screen version of the musical will happen, other than a new studio, Paramount (not Fox), is involved in the remake.

A Unique Record of Sorts

Finally, Adiarte shares a rare Broadway-Hollywood honor with three other actors. Dwight Chapin, president of RHO, once called Shirley Jones “Broadway royalty” because she had come to the attention of producer-composer Richard Rodgers and was personally groomed by the RHO towards her breakout role as Laurey for the Oklahoma! film.

Like Jones, Gordon MacRae, and Juanita Hall, Adiarte, in a way, is also true Broadway royalty, having debuted as the Siamese Crown Prince and being one of only four actors to have appeared onscreen in two definitive Hollywood film versions of R&H musicals. Adiarte was also the youngest and the only one of Filipino descent. He and Jones are the only two “royals” still around today.

The Only Four Actors to appear in two major Rodgers & Hammerstein film musicals each:

Shirley Jones, 1934 -

Gordon MacRae, 1921-1986

Juanita Hall, 1901-1968

Patrick Adiarte, 1942- today.

Not bad for a kid from Manila who left his war-torn country without a father.

Sources:

Interviews with Patrick Adiarte

Musical Stages: An Autobiography by Richard Rodgers, Random House, © 1975, p.270

Something Wonderful, Todd S. Purdum, Henry Holt & Company, © 2018, p.247