The Last Night of I-Hotel

/Thousands of supporters surround the I-Hotel to stop the eviction. (Photo by Chris Huie)

Meanwhile the battle raged outside. Two thousand people chanted and screamed as bullhorns blared and police sirens screeched. A few blocks away, police barriers kept thousands more from joining the protesters. In the end, the resistance was of no use. Upon orders from the San Francisco sheriff, 300 police officers in riot gear advanced, using their horses and clubs to break through the human barricade. Using sledgehammers, the police raiding party broke down the doors of the residents. As the elderly tenants were led away from their rooms, the media recorded each step. The manongs’ faces showed a silent dignity, even as their pained eyes looked searchingly at the cameras. “What will happen to us?” They seemed to be asking. “Why?”

End of an Era

The fall of the International Hotel on August 4, 1977 marked the final demolition of what had been a thriving community known as Manilatown. Formerly occupying a ten-block strip, the area once bustled with businesses that catered to San Francisco’s emerging Filipino community. In its heyday, Manilatown was populated by nearly 10,000 Filipinos, and at the heart of it all was the 100-room International Hotel.

“Everyone went through the I-Hotel,” reminisces Bill Sorro, community activist and former tenant. “People first coming to this country, migrants following the crops … it was where you went to get connected.” It was also the place where elderly Filipino men, some of whom were veterans of World War I or II, or were former cannery or migrant workers, came to retire. Because of the anti-miscegenation laws of their time, which forbade them to marry outside their race, these men now faced their twilight years without families. As a result, they served as guides and mentors to those like Sorro, who was drawn to the hotel as a young man.

“There were a bunch of us students, mostly Asians, who volunteered our time there,” says Sorro. “We’d clean the bathrooms, make repairs—basically doing things to ensure that the manongs could live comfortably and with dignity.” What they received in return were lessons in their culture and the generous spirit of the Filipinos.

“A lot of the old people used to just open their doors and invite the students in to eat and to share what they had. It was so surprising to some of these kids, who hadn’t been exposed to Filipinos, to be invited into someone’s home and be treated with respect; to be treated as an honored guest.”

Sorro continues, “The really amazing thing was when someone, usually a single mom, would move in with kids. All of a sudden, her kids would have ten grandfathers playing with them, looking out for them. It didn’t even matter whether they were Filipino!”

“The manongs’ faces showed a silent dignity, even as their pained eyes looked searchingly at the cameras. “What will happen to us?” They seemed to be asking. “Why?””

Bought and Sold

This community and its way of life were soon jeopardized, as the rapid expansion of San Francisco’s financial district made the land under Manilatown too valuable to use for low-income residences.

In 1968, the owner of the I-Hotel, real estate developer Walter Shorenstein, decided to build a parking lot at the site. This galvanized community activists and church leaders who rallied to protect the tenants from eviction.

Thus began the nearly decade-long battle to stop the building from being destroyed. Former resident Emil de Guzman was a student at UC-Berkeley at the time. “We’d picket Walter Shorenstein’s office, we’d file one legal motion after another,” he explains. “We worked to keep the battle visible.” Adds Sorro, “There were a lot of really good lawyers working pro bono on this case. We were very lucky.”

In 1974, Shorenstein, perhaps tiring of the struggle, sold the property to the Four Seas Investment Corporation, a Thai company. Shortly after taking control of the I-Hotel, the new owner, Supasit Mahaguna, a liquor baron known in Thailand as “the Godfather,” instructed his property managers to deliver eviction notices to the tenants.

The struggle reached a crisis point. In October 1974, the San Francisco Lawyers Committee for Urban Affairs filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction against Four Seas. They lost the suit. Appeals for a stay of eviction also eventually lost, and an eviction was ordered by the end of 1976. When San Francisco Sheriff Richard Hongisto refused to carry out the eviction, he was jailed five days for contempt of court in January 1977.

For the next six months, Sorro, de Guzman and other activists worked feverishly to fend off what had now become a high-stakes struggle. They were helped by the rising tide of public support. At times, as many as 5,000 demonstrators would gather in the streets surrounding the I-Hotel. More importantly, they were strengthened by the examples of the people they were trying to protect. Twenty years later, de Guzman still speaks of them with respect.

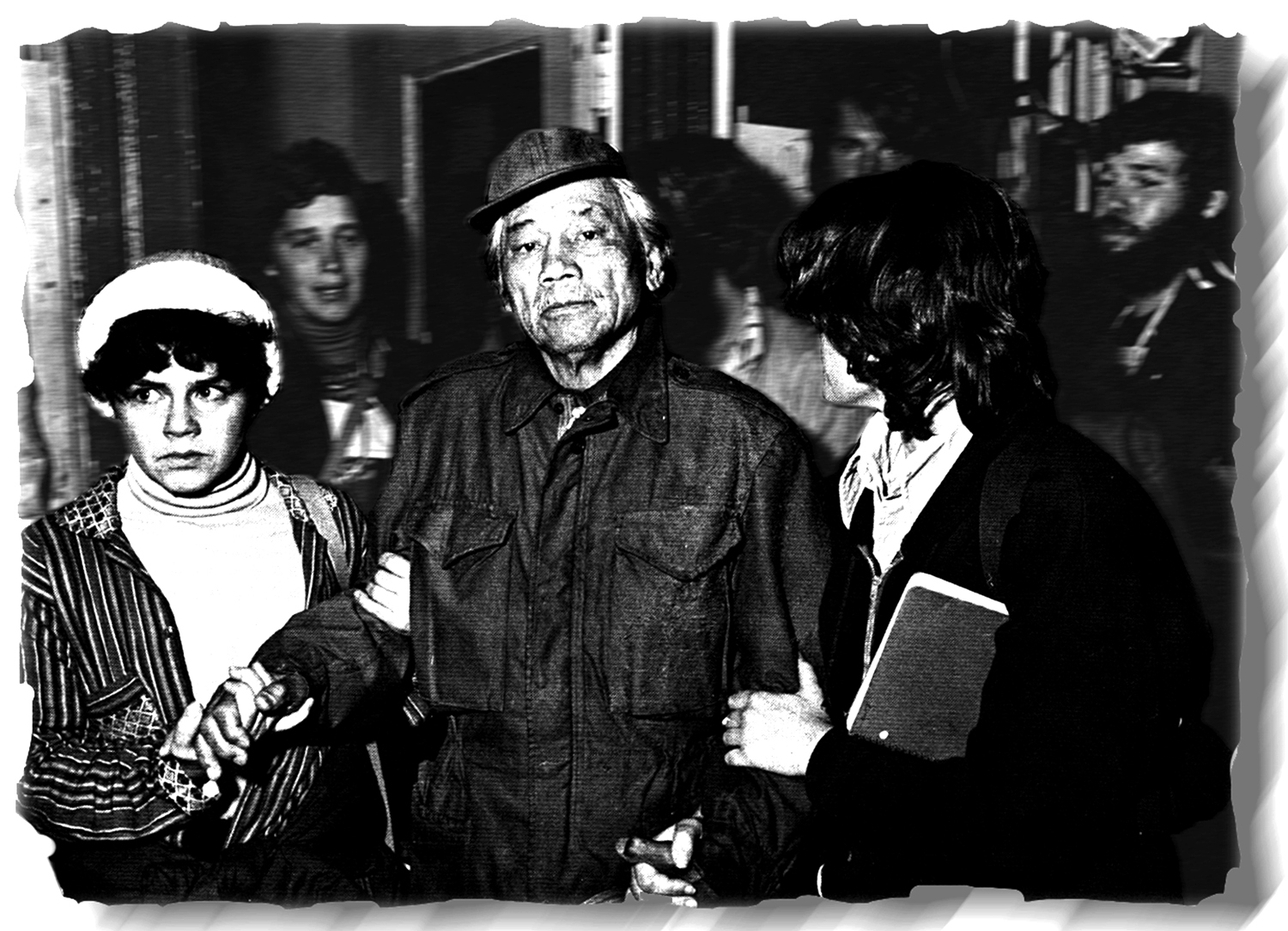

When the fight was over, Filipino tenant Felix Ayson and other Asian residents left the building with quiet dignity and sadness. (Photo by Chris Huie)

“The media at the time criticized us (students) for taking over the struggle, but they were very wrong. The housing board of the I-Hotel consisted of the elderly, and I was always amazed at how they could comprehend the complex legal issues surrounding the struggle. Don’t forget, these were people who were laborers, not college-educated individuals. Not only that, but when presented with the facts, they were often much more capable than the rest of us in making objective, dispassionate decisions.”

“I was an angry young man,” Bill Sorro recalls, “and I was fighting for people who were being forced out on the street, but I can still hear them telling me, ‘Bill, do not be so mad. It is not good to be like this.’”

In the end, however, the developers triumphed, and in the middle of the night, the residents of the International Hotel were forcibly removed from their homes. Two years later, the building was razed, and Manilatown became a memory.

People’s Rights vs. Property Rights

The emotional appeal of protecting manongs from homelessness is an easy one for Filipinos. Considering, however, the thousands of people who protested and the lawyers and community leaders who supported the tenants, it’s obvious that the International Hotel represented much more than a Filipino, or even an Asian, cause. How did the plight of a few dozen elderly men draw so impassioned a response from so many people?

For Nancy Hom, artist/activist and executive director of the Kearny Street Workshop, it was witnessing the slow disintegration of a community that agitated her. “Most people are familiar with Chinatown or Japantown,” she states. “Imagine growing up in that neighborhood, or going to eat there, or seeing your relatives there. Then each year you’d see one building disappear. It would go on like that until there was only one building left of your community. That was the significance of the I-Hotel.”

For others, the removal of the aged and the poor from their homes for the sake of commerce was the reason. Low-income, decent housing was destroyed without regard to providing alternative shelter for the former tenants. A common rallying cry at the time was “people’s rights versus property rights,” and it’s an issue that remains to this day.

San Francisco community leaders gather to commemorate the anniversary of the I-Hotel eviction in 2002 and to celebrate the eventual construction of affordable housing on the hotel’s old site. (L-R) Manilatown Heritage Foundation President Emil de Guzman, San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, City Supervisors Aaron Peskin and Tom Ammiano. (Photo by Cherie Querol Moreno)

Lessons

The legacy of the International Hotel was celebrated during a week-long event in San Francisco, marking the 20-year anniversary of the August 4 eviction. After a performance of the Pearl Ubungen Dancers and Musicians, former I-Hotel supporters gathered around the corner of Kearny and Jackson streets, renewing old friendships and reminiscing well into the night.

For many, the effects of that struggle have been far-reaching and deep. Bill Sorro, the “angry young man,” is still angry today. As he continues his crusade to provide affordable, decent housing for low-income families, he’s left grappling with unanswered questions. What happened was a tragedy, no doubt about it. But more importantly, Sorro says, Filipinos have to ask themselves how it came to be that communities such as Chinatown, Japantown and North Beach (San Francisco’s Italian neighborhood) thrived and are, in fact, tourist attractions today, when Manila-town was destroyed.

Although living and working at the I-Hotel was a “once in a lifetime opportunity” for Emil de Guzman, its lessons are even more significant for today’s younger generation of Filipinos. “Manila-town was an important, critical point in Filipino American history. It’s important for us to understand that we have roots in this country, that in the face of racial abuse, of anti-miscegenation laws, there was a community of 10,000 people who paved the way for those who came afterwards.”

Nothing was ever built on the site of the old International Hotel—not the parking lot Shorenstein had planned, or the commercial property the Four Seas trading company wanted. For 20 years the site of the old hotel has remained a fenced-in hole in the ground.

But soon a new International Hotel will rise again. An alliance of San Francisco community groups, such as the Manilatown Heritage Foundation, the Chinese Community Housing Corporation, the Kearny Street Housing Foundation and the I-Hotel Citizens Advisory Committee, are working together with the Archdiocese of San Francisco, which got an option to purchase the site several years ago. Current plans call for 104 units of subsidized senior housing, funded by a loan from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The site will also contain the Manilatown Museum and Cultural Center, the first Filipino American museum and cultural center in San Francisco. Each floor will be named for a prominent former tenant, and a wall made of glass or granite will list the names of the tenants evicted on the night of August 4.

Years later, the humble, gentle ways of those laborers and veterans live on in the men and women whose lives they touched. Through them, the spirit triumphs.

In 2004, the new I-Hotel was completed. The Manilatown Museum and Cultural Center, ran by the Manilatown Heritage Foundation, has since become an active site for Filipino American cultural activities.

First published in Filipinas Magazine, October 1997, this article is also included in the book, Filipinos in America: A Journey of Faith (Filipinas Publishing Inc., 2003).