The ‘Indio Hacendero’ of Angono

/From left to right: Gene Lara, Dr. Deborah Guido Ruiz Wall and Dr. Luciano P.R. Santiago, descendants of the owners of Hacienda de Angono, Angkla Art Gallery, at Wall’s presentation ‘Biga: Mas malalim pa ang kasaysayan ng Angono: A Historical Review Beyond Angono, Art Capital of the Philippines’, April 2018.’

Many years ago, I had wanted to meet him after I came across an article he wrote, “Don Pasqual de Sta. Ana (1762-1827), Indio Hacendero,” Philippine Studies, Vol 50. 2002: 23-49. His richly documented archival research for that article helped me see through the strands of my Indio and Spanish heritage. When I finally met him in 2010, he said, “I am your distant relative.” He showed me the modernized back part of the Santanas’ (modified surname of Sta. Ana) ancestral home in Pásig, Rizal.

In a tribute to Dr. Santiago, the Pasig City Museum outlined some of the prizes and awards he received in his lifetime: Outstanding Pasigueño Award on History in 1994; the National Book Award for Art and for History (from the Manila Critics Circle); The Wendell Muncie Prize for Distinguished Writing in Psychiatry (from the Maryland Psychiatric Society); The Premio Manuel Bernabé (Primer Premio) in History (from the Centro Cultural de la Embajada de Espana); the Dr. Pedro Villaseñor Award for Genealogy; the Catholic Author Award (from the Asian Catholic Publishers); the Catholic Press Award (from the Archdiocese of Manila), and a Research Grant Award from the Toyota International Foundation Psychiatry of the Medical City Hospital in Pásig City.

Patsy (Maria Paz) Santana, Deborah Guido Ruiz Wall and Dr. Luciano P.R. Santiago, Sta. Ana/Santana ancestral home, Pásig, Rizal, 2010.

Through the years, my mother told us many stories about her forebears — Guidos, Laras, and Sta. Anas, who were mentioned in relation to the Hacienda de Angono. I didn’t take much notice. Until I read Chito’s article. I knew that one day, I would dig deeper into this phase of Philippine history that has some connection with me. That day came. In 2018, I flew from my home in Sydney to Manila to do my ancestral research. Balaw Balaw, a restaurant-art gallery-museum in Angono, Rizal was my base. I stayed there for three months immersing myself in the community.

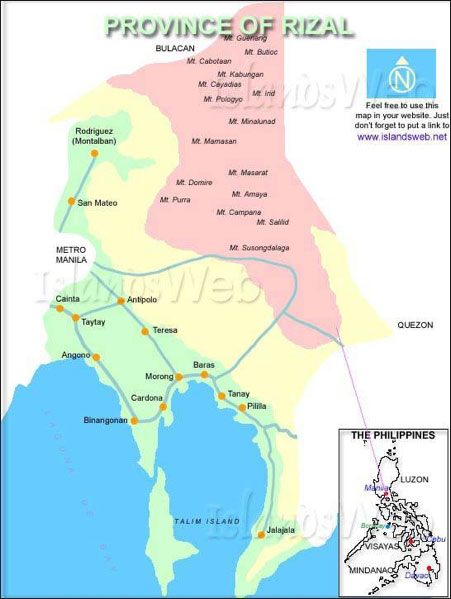

Map courtesy of wwwislands net.web

A glimpse of the former Hacienda de Angono (Photo by D. Wall, March 2018)

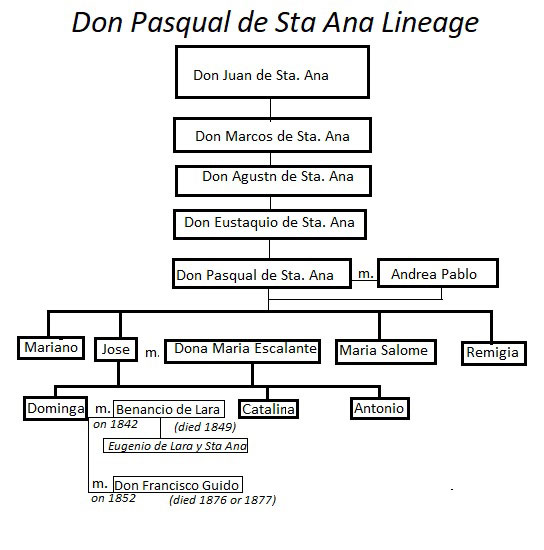

I found the term “Indio Hacendero” baffling. How could an Indio (native) be part of the ruling class during the Spanish colonial regime in the Philippines? Land was the main measure of wealth, power and prestige. The subject of Chito’s article was Don Pasqual de Sta. Ana who was born in 1762. An Indio, Don Pasqual, was our common forebear. Don Pasqual came to acquire two haciendas. Haciendas were a huge landholding, a formally organised estate, officially recognized by the colonial government and regulated by particular laws of the Indies. The owners of haciendas were mainly Spaniards or Spanish institutions.

Don Pasqual bought Isla de Talím in 1812 and Hacienda de Angono in 1818. The rise of entrepreneurs, mostly Chinese mestizos, at the turn of the 18th century into the 19th enabled some entrepreneurs to acquire some lands from confiscated Jesuit haciendas through public bidding in 1795. The Jesuits were banished in 1768.

The Sta. Ana clan, according to oral tradition, belonged to the pre-Hispanic nobility of Caintá and Pásig. The Sta. Anas made the transition to the landed gentry after the Spanish colonization of Central Luzon. The Jesuit chronicler, Chirino noted that Caintá was ruled by a rajah on the scale of Manila and Cebu at the time of the Conquest. However, when Don Pasqual was growing up, his family were not doing too well financially as a result of the devastation caused by another invader, the British (1762-64). Some Sepoy soldiers in the English army from that time decided to make Caintá their home. Don Pasqual and his descendants later employed on their farms the Sepoys and their children with native women. Don Pasqual’s great-great grandfather, Don Juan and his great grandfather, Don Marcos, along with the other principales from Cainta, represented the town before the special commission to investigate the causes of the Agrarian Revolt of 1745-46. The revolt was essentially the protest against landgrabbing by Spaniards of the natives’ ancestral lands.

The principales were traditional local leaders that had local wealth, high status and prestige. They were prevailed upon by the Spaniards to join the Spanish administration as part of the colonial pacification strategy. They were offered privileges, appointed to local offices, and exempted from paying tributes (taxes). Their leaders’ incorporation into the establishment enabled the Spaniards to rule in remote rural areas indirectly. The principales were from the pre-colonial royal and noble class of Datu of the established kingdoms of rajahnates, confederacies and principalities. Don Juan de Sta. Ana and Don Marcos de Sta. Ana along with the other principales questioned the boundaries of the Jesuit Hacienda de San Isidro Labrador de Mariquina which, they argued, encroached on their communal lands.

Don Augustín de Sta. Ana, Don Pasqual’s grandfather was partly the cause of the clan’s financial woes. By dire circumstances, he was forced to lose their ancestral lands, mortgaging them one by one to various people. Don Pasqual’s parents had failed to redeem their ancestral lands, but their eldest son, Don Pasqual, succeeded. Don Pasqual and his wife, Andrea Pablo, of Pásig, recovered their lands and furthermore, purchased rice lands in Pásig and neighboring towns, paraos (passenger and cargo sailboats) and cascos (long covered boats). The couple became rice traders, using the boats to ply the Pásig River and Laguna de Bae. The commodities that passed through the Pásig river helped feed the people of Pásig and the rest of the province of Tondo. In 1798, the principalia of Pásig elected Don Pasqual gobernadorcillo — a position that had functions similar to a town mayor. The leader of a pueblo (town) at that time was the gobernadorcillo.

Don Pasqual’s four children, Mariano, Jose, Maria Salome and Remigia, all did well and married with the upper classes. Don Jose’s marriage was considered the best match. He married Doña Maria Escalante, the Spanish widow of Don Jose Matheo de Rocha, son of Don Luis de Rocha who was the owner of the Malacañang estate (the future site of the presidential palace). An Indio marrying a Spanish woman was considered taboo. Perhaps an exception was made of the son of the Indio hacendero Don Pasqual de Sta. Ana of Pásig. And so began a mixed Spanish-Indio ancestral line within the Sta. Ana clan through Don Jose’s children: Doña Dominga; Doña Catalina and Don Antonio, as depicted in the chart below.

Don Pasqual died in 1841. Catalina, his daughter died in 1842. Around 1844, Don Antonio was involved in a serious legal case that led to his imprisonment for four years. Doña

Dominga de Sta. Ana emerged as the heiress of the Hacienda de Angono. The Spanish mestiza had many suitors who were prominent Spaniards. She chose Don Benancio Gonzalez de Lara, a lawyer from Toledo, Spain, who worked in Cebu as the asesor del gobierno y la intendencia de las Islas de Visayas. They married in 1842 and spent their honeymoon in Spain, leaving powers of attorney in the islands to her mother, Doña Maria Escalante. On the couple’s return after two years of absence, they settled in Cebu. Don Benancio was promoted to Lieutenant Governor of the Province. Their only child, Don Eugenio Gonzalez de Lara (1844-1896), was born there. In 1849 while on business in Spain, Don Benancio died unexpectedly. His widow and two-year old son, Eugenio returned to Angono.

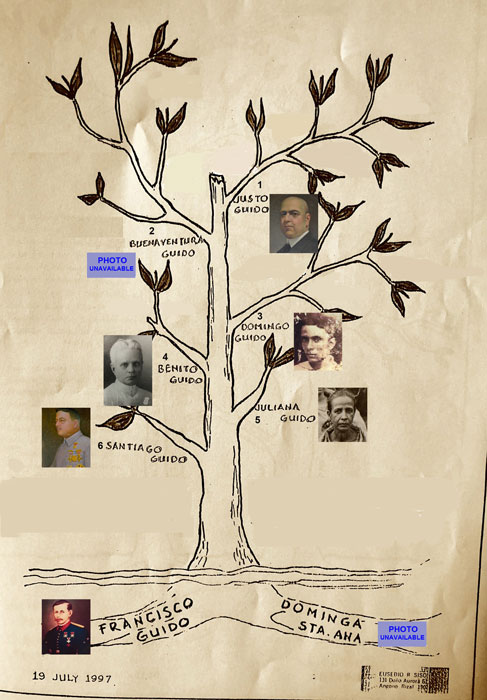

Doña Dominga’s next husband was my great-great grandfather, Don Francisco Guido y Pérez, comandante graduado y capitan del Regimiento Infanteria. He originated from Villafranca del Bierzo, Léon Province, Spain. The couple were married in 1852 and had six children: José Santiago; Julian; Justo; Benito; Domingo; Buenaventura. Don Buenaventura was my great grandfather. One of his sons, Hermógenes, was my grandfather. Hermógenes had ten children. Eufronia, my mother, was one of them.

Captain Francisco Guido y Perez, Spanish husband of the heiress, Doña Dominga de Sta. Ana

Family tree of Don Francisco and Doña Dominga (Courtesy of Eusebio R. Sison), 1996

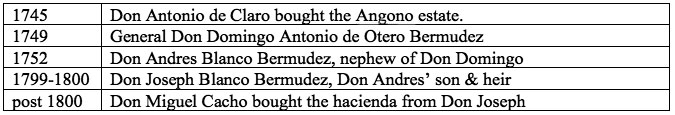

The tenants of Hacienda de Angono questioned its proprietorship and complained of Don Francisco’s high-handed manner of management. They argued that the owners of the hacienda and their predecessors usurped the estancia (farm), which belonged to the ancestors of the tenants. The deed of sale of the hacienda in 1818 was deemed insufficient evidence of ownership of the entire estate. Don Francisco took 18 years to present antecedent documents (1699-1752) to court. Don Francisco won the case against the tenants and in 1872, the court ordered the plaintiffs to turn over to Don Francisco the lands they took over during the litigation.

List of Spanish hacenderos (1745-post 1800s)

List of Indio hacenderos (1818-post 1897)

The main disputes over the land ownership of Hacienda de Angono

The tenants’ refusal to pay the hacendero the customary fees (terrasgo) for their houses and fruit-bearing trees inside the hacienda

The tenants’ claim of prior jurisdiction over the estate that was sold

The tenants’ claim that the estancia (farm) belonged to their ancestors

The title holders’ claim that the tenants had no evidence of proof of ownership and had failed to appreciate the pertinent land laws.

Don Francisco’s trouble was far from over. In 1864, his wife filed for the annulment of their marriage at the Ecclesiastical Court in Manila. She also filed civil suits against her husband. In 1869, Don Francisco’s stepson, Don Eugenio asked the District Court of Binondo to compel his stepfather to produce a complete financial accounting of his guardianship. Don Francisco declared bankruptcy, arguing that he was forced to sell his half of the Hacienda de Angono to Don Manuel Genato of Quiapo in order to meet his financial obligations. In 1872, the District Court of Intramuros disapproved his claim of bankruptcy and ordered him to pay the total cost of the proceedings. Half of the Hacienda de Angono was embargoed to enable Don Francisco to pay back his wife the income for the past three years of the other half of the estate, which belonged solely to her. Plagued by legal suits and stress, Don Francisco died in 1876 or 1877. Don Manuel Genato then approached Doña Dominga for a compromise agreement. In exchange for recognizing the validity of the sale eight years earlier, Don Manuel promised to sell his part of the estate to Doña Dominga’s children for the same purchase price of five thousand pesos. Around 1885, Doña Dominga died. Her eldest son, Don Eugenio took control of the hacienda and in 1886, he sued the towns of Antipolo and Teresa for claiming parts of the family estate. Don Eugenio won the suit after he produced all the relevant documents of the property.

At the height of the Revolution against Spanish rule in 1896, the tenants of the hacienda supported the cause of overthrowing the colonial government. Andres Bonifacio formed a chapter of the Katipunan in Angono in 1894. Don Eugenio and Don Justo, likewise, became underground staunch supporters of the Katipunan. Don Eugenio was killed by a mob who broke into his house perhaps assuming that, being a cuarteron (three-quarters Spanish), he was likely to stand on the side of the colonial administration. For supporting the revolution, his half-brother, Don Justo was imprisoned by the authorities, later pardoned by Governor General Don Camilo de Polavieja along with other prominent people, to mark the natal day of the boy King, Alfonso XIII on 23 January 1897. After Don Eugenio’s death, the Lara clan never returned to the hacienda.

Don Eugenio’s son, Captain Cárlos de Lara became the Chief of Police in the early American regime. Like his father, he met a tragic death. He was shot dead in 1900; his assassin was never found.

(Courtesy of Gene Lara)

In 1903, the heirs of Don Francisco Guido — Juliana, Justo, Benito, Buenaventura and the children of their deceased brothers, Jose Santiago and Domingo -- bought back the other half of the hacienda from Don Manuel Genato for the original price of five thousand pesos. The townspeople of Angono claimed that the heirs usurped the land on which their houses were built. The tenants lost the case in 1907. In 1909, Don Justo with his three surviving siblings had the estate registered under the American Torrens title system. Don Justo had three children: Joaquin, Victoria and Benito. Doña Juliana was unmarried and died in 1925. Don Buenaventura had three sons, Francisco, Isidro and Hermógenes and a daughter, Isabel. Isabel did not have children. Isidro was not legally recognized. The names of the children of the three other brothers — José Santiago, Domingo and Benito -- had not appeared in the documents. José Santiago became a soldier and died in Cuba. Benito moved to Poon Bato in Zambales to join his Ayta wife. Hermógenes, my grandfather, became an engineer and wrote novels in the early 1930s, some of which were turned into the first Tagalog talking films. He was co-director with José Nepomuceno in the film production of his novels. During World War II, Hermógenes died, on 17 June 1943.

Three of the original manuscripts of Hermógenes B. Guido’s novels (1930s) (Courtesy of Profetíza Guido Manijayme and Deborah Guido Ruiz Wall)

One of Hermogenes Guido’s films. Basag na Batingaw (Courtesy of Deborah Guido Ruiz Wall)

Dilim at Liwanag, a Hermogenes Guido film (Courtesy of Deborah Guido Ruiz Wall)

Lt. Col. José “Pepito” Guido (son of Benito Guido) married his first cousin, Justa Guido (daughter of Justo Guido). José was beheaded by the Japanese in front of his three sons who were subsequently killed by machine gun fire.

In 1969, Captain Eugenio G. Lara, a graduate of the Philippine Military Academy (1938) and a descendant of hacendero Don Eugenio Lara, produced a manuscript, Readings on the History of Angono, now used in the town as a reference material in local history.

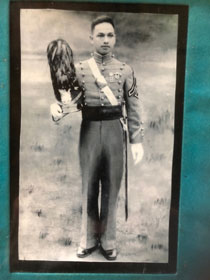

Captain Eugenio G. Lara, 1938 (Courtesy of Gene Lara)

In 1991, the Guido clans’ proprietorship of the lands formerly part of the Hacienda de Angono was confirmed by the Supreme Court. The heirs parted with 500 hectares so as not to dislocate some tenants who had occupied lands for several years. The Hacienda de Angono continued to be beleaguered by many legal suits. The heirs’ hold on the estate had slipped away. Among the younger generations in Angono, the history of the hacienda from the 18th century is hardly known. My “distant relative,” Dr. Luciano “Chito” P.R. Santiago’s work helped us all catch a glimpse of the tug of war between the old and the new, the cycle of usurpation and retribution, and the unfolding of history of land disputes in our times.

Deborah Ruiz Wall, PhD OAM is a Filipino Australian born in Manila. Her completed oral history projects included Aboriginal and Filipino women in inner city Sydney, Western Sydney and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians of Filipino descent in Broome, Western Australia and Torres Strait.

More from Deborah Ruiz Wall