The Image That Never Left Me

/I began reading report after report – mostly by Amnesty International and the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines – and eventually stumbled upon a “Report of a Fact-Finding Mission to the Philippines” (November-December, 1983) jointly sponsored by five medical and scientific organizations in the US, including the American College of Physicians, American Committee for Human Rights, and the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences.

On page 11 of the (now almost impossible to find) 15-page report were photos of a man – Buenaventura Tampipi, a 37-year old farmer from Matanao, Davao del Sur – who had been found earlier that year with a four-inch nail protruding from his head. The report continued: “The shank of the nail was driven straight back into his brain above and directly between his eyes. Mr. Tampipi was paralyzed on the right side of his body and unable to speak.” In the end, the surgeons decided it was too dangerous to remove the nail and only treated him with intravenous antibiotics. After two weeks, he failed to improve, so his family took him home, still aphasic and paralyzed. Eventually, Mr. Tampipi died.

Buenaventura Tampipi. Report courtesy of the Medical Action Group.

Other images of Tampipi can be found in European and American medical journals featuring the research of Dr. Hermann Vogel, including this October 2009 photo in the Guardian.

I remember trying to grasp the enormity of what his suffering must have been like during those final weeks. Hospital records indicated that he had been detained at the Matanao Municipal Hall, where he was tortured, his family alleged, by the Civilian Home Defense Force. But their efforts to bring the case to the National Bureau of Investigation’s attention repeatedly fell on deaf ears. Somehow the image has always stayed with me, filling me with that vague sense of dread I have always carried. Over the years, I read about other harrowing cases, many of which haunt me to this day.

Growing up in the shadow of Ferdinand Marcos -- the nephew of my grandma (Angela “Ilang” Marcos Valdez Ramos) and the second cousin of my mom (the late Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani) and my uncle (former President Fidel “Eddie” V. Ramos or FVR) – had always been, in the early years at least, an uneasy point of pride. My Lolo, Narciso Ramos, had been part of Marcos’ now-debunked ‘Ang Mga Maharlika’ group, a six-term congressman, and eventually his foreign secretary. Mom and Uncle Ed had been civil service professionals who moved up the ranks in their respective careers, but the hierarchy within the extended family was always clear: they were merely Marcos’ subordinates, forever seen by Imelda Marcos as “poor relations.” Still, Marcos remained very fond of my Lola Ilang, even helping to carry her casket when she died.

Debut of my late mother (center), Leticia R. Shahani, in Washington, D.C; 1947. She is flanked by her parents, with a young Ferdinand on her far left. Photo: Shahani family collection.

President Marcos and my grandma, Angela V. Ramos, in Malacañan Palace; early 70s. Photo: Shahani family collection.

Eventually, however, the Ramos-Shahanis, like many Filipinos in the years leading up to EDSA 1, would turn away from the Marcoses because of their incalculable excesses and abuses.

Even when I was growing up, when my Lola (grandma) would say that Uncle Eddie was a man of great compassion (unlike General Fabian Ver, who was “unnecessarily harsh” towards detainees), I wanted proof. I would follow my mother from room to room, repeatedly asking her questions she never had the time to answer. Eventually, I wrote my Uncle Ed an open letter, where I broached, once again, the question of human rights (http://lilashahani.blogspot.com/2009/10/open-letter-to-fvr.html). For well over a year, I became persona non grata with his wife, my Auntie Ming, and my Ramos cousins. But Uncle Eddie was the one member of his family who remained an intellectual sport throughout, graciously writing me letter after letter explaining the economic gains during his term. While I knew all this to be empirically true, his continued silence on the question of human rights remained deafening. I was particularly concerned about the 5th Constabulary Security Unit (CSU) in Camp Crame, where numerous torture victims had been detained.

Later, I began to read Al McCoy, Robert Youngblood, Eva-Lotta E. Hedman, Ronald J. May, Susan Quimpo and younger scholars like Xiao Chua; I also had lengthy conversations with former detainees, many of whom would eventually become my friends. The general sense I got from these many conversations was that, as chief of the Philippine Constabulary under Marcos, FVR must have had an idea about what was happening under his watch, but he did not directly order, let alone orchestrate, torture sessions, unlike General Ver, Marcos’ chief henchman. This was eventually corroborated by official documents in the human rights class action suit against Marcos in Hawaii, where Ver is explicitly named, among others.

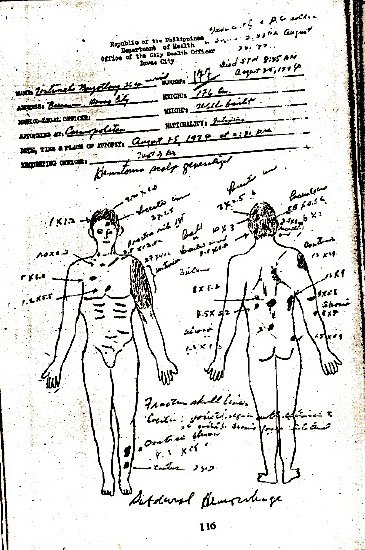

Fast forward 35 years. EDSA 1, to put it kindly, remains unfinished. One might even suggest that all post-EDSA administrations failed the spirit and intent of People Power. The point is: the Marcoses are back in full force as a Bongbong presidency looms large. All this has forced me to go back to the past, tracing the photo that had marked my loss of innocence. I have since found it in the work of Dr. Hermann Vogel, a German radiologist, in such publications as the European Journal of Radiology; A Radiologic Atlas of Abuse, Torture, Terrorism, and Inflicted Trauma (Routledge); and the Guardian (above). But why is Mr. Tampipi’s story almost never discussed in the Philippines? How is it that he and his family have been forgotten? What of other so-called “dissidents,” like Fortunato Bayotlang, whose body was found in 1974 with multiple lacerations, contusions and fractures in Davao?

Fortunato Bayotlang. Political Detainees in the Philippines, Task Force Detainees of the Philippines/Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines, 1976. Book courtesy of the Bantayog ng Mga Bayani.

What of Dr. Johnny Escandor of the Philippine General Hospital, who was found dead in early 1983 with dirty rags, socks, soiled briefs and plastic wrapping inside his cranial cavity? The pathologist who performed the autopsy could not even write a histopathology report down and, to this day, remains too fearful to be interviewed. This is also true of Dr. Escandor’s former colleagues, friends, and family, almost all of whom did not respond to my questions. There were countless women like Etta Rosales and Maria Elena “Malen” Ang, too, with whom I have had lengthy conversations. Decades later, Malen still finds herself trembling at the sound of boots on cement floors, refuses to go into the water, avoids electric wires, and has difficulty sleeping. If she is not vigilant, flashbacks about her detention (and the water cures, electric shocks, and sexual abuse she experienced) come flooding back in an instant.

Etta Rosales (center) and Malen Ang (right) with other detainees, Camp Bago Bantay, Manila, 1976. Photo courtesy of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines.

Fast forward, once again, to Rodrigo Duterte, under whose presidency there has also been an untold loss of human life. While most of the drug war victims have been killed swiftly (dispensing with the theatrical spectacle of torture characteristic of the Marcos years), the gratuitous violence enacted upon their dead bodies is a grim reminder of Dr. Escandor’s chilling fate in the early ‘80s.

Photo by Ezra Acayan (2016), cited in Vicente Rafael’s Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Duterte, Duke University Press, 2022.

It also cannot be denied that torture of those who have been “red-tagged” continues to take place. If the treatment of detainee Reina Mae Nasino and her dead baby River indicate how activists among the poor are treated in this administration, the autopsy of Randy Echanis speaks louder than words.

Excerpts from the autopsy report of Randall Echanis, September 2020. Courtesy of Anakpawis Partylist, c/o Karapatan.

With the recent enactment of an alarmingly broad Anti-Terrorism Law (co-authored by Bongbong’s sister Imee) and Duterte’s “Lingkod Bayan” proposal to arm civilian militias (reminiscent of vigilante groups like the Civilian Home Defense Forces in the mid-‘70s, Alsa Masa and Tadtad in the ‘80s, and the Citizen Armed Geographic Units after EDSA), one can only imagine what a Bongbong/Sara tandem – as the proud and unapologetic offspring of Marcos, Sr. and Rodrigo Duterte – will look like for so-called “dissidents.”

The Bongbong/Sara message is clear: despite the official statements of US and Philippine courts, Bongbong continues to claim that torture did not happen under his father’s watch. His sister Senator Imee claims that, at the age of 21, she was still too young to know about the death of Archimedes Trajano, who was tortured on her behalf. So, what does this say about how human life will be valued in a Bongbong presidency? As for Inday Sara, who claims that she was not offended by her father’s notorious rape joke about an Australian missionary -- adding that she, too, had been raped – how can she support a father who dismisses her as a “drama queen” for recounting this traumatic experience? How will she, in turn, represent female survivors of assault and rape if she herself is apparently no feminist? What we do know is that, like her father and running mate, she is not averse to extrajudicial action, as her repeated punching of a Davao sheriff in 2011 all-too-clearly demonstrates.

To those who remain undecided about a Bongbong vs. Leni presidency, I ask simply: is this the kind of leadership you want for the country? Do alleged dissidents among the poor deserve to be tortured for their beliefs or for resisting violence and injustice? Are alleged criminals and small-time drug users not entitled to representation in our admittedly-flawed justice system?

Indeed, these flaws highlight the power and ubiquity of class discrimination in the Philippines, where the poor can be tortured at will, often with no consequences. Torture is something no human being, regardless of their background, should ever have to experience. Because I believe in the sanctity and equality of human life, I support a president who will do her utmost to uphold it. I say we break away from this culture of violence and impunity, and the fear and silence it spawns. I say we remember our painful history, cherish its critical gains, and vote for a leader like Leni.

Lila Ramos Shahani is an Expert Member of the International Scientific Committee for the Interpretation and Presentation of History (ICIP), International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). She is the former Secretary-General of the UNESCO National Commission of the Philippines.

She would like to express her heartfelt thanks to the former detainees and their families, as well as the human rights advocates and medical/forensic specialists -- from Karapatan, SELDA, Medical Action Group, Task Force Detainees of the Philippines, Bantayog ng Mga Bayani, Commission on Human Rights, Martial Law Memorial Museum, Anakpawis Partylist, Amnesty International and others --who provided her with critical material and patiently answered her endless questions throughout.