The Ibong Adarna, an Enduring Enigma

/It’s been celebrated and immortalized in the spoken word, Filipino graphic novels, stage, on screen, and in dance. It’s the Alamat ng Ibong Adarna (Legend of the Adarna Bird). It’s one of the Philippines’ own folk epic poems/stories—like “The Iliad,” “The Odyssey,” “The Ramayana,” “The Nibelungenlied,” “Chanson de Roland,” etc., of other cultures—and more specifically, for Filipino lore, it’s right up there with Florante at Laura.

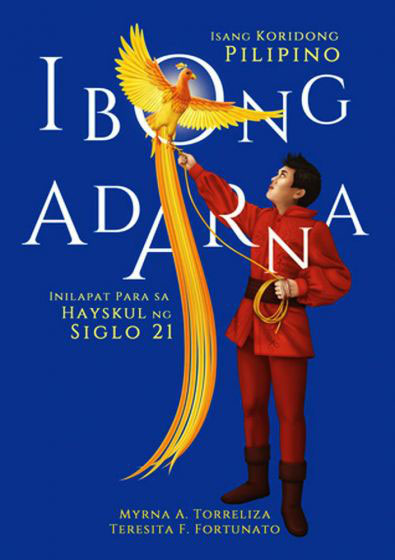

Following are various samples of visual interpretations of the story:

A paisley-inspired interpretation by Paul Vito

This artwork by Rosalinda Rocco

Cover artwork from a Juliana Martinez Books edition, © 2005. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibong_Adarna#/media/File:Ibong_Adarna.jpg

There is no literal English translation for “Adarna”; otherwise, it’s just the Magic or Enchanted Bird.

The epic poem has no exact date of origin, but it is definitely an adaptation of an old European legend. While its original author remains unknown, it is believed that the epic was put to rhyme by Huseng Batute, pseudonym of Jose Corazon de Jesus (1896-1932). Corazon de Jesus, dubbed “King of Tagalog Poets,” used Spanish-inspired names and locations when he finally put the legend down on paper.

It’s a long, complicated saga told in poetic form and meter. Its complete title alone is a record- and jaw-breaker: “Corrido at Buhay na Pinagdaanan nang Tatlong Principeng Magkakapatid na Anak nang Haring Fernando at ng Reina Valeriana sa Kahariang Berbania” (The Corrido and the Life of Three Princes, Sons of King Fernando and Queen Valeriana of the Kingdom of Berbania).

A corrido is a metrical romance that involves the struggles of a heroic character. It tells of adventures and magical powers, romance and love, courage and piety, and treachery and betrayal of highborn characters. In other words, it’s perfect for an interminable soap opera series.

The familiar theme of a sick sovereign seeking healing from a magical bird comes from an old Chinese tale, which 19th century Danish storyteller Hans Christian Andersen adapted in his The Emperor and the Nightingale. As with any folkloric epic poems handed down through the ages, there are many conflicting versions of the tale.

Ibong Adarna tells the story of three princes of the mythical kingdom of Berbania. Their father, King Fernando, has fallen into some deep melancholic state (probably, depression) but somehow divines that only the song of the enchanted Ibong Adarna will cure his royal blues.

The three princes, Pedro, Diego, and Juan, set out to find the magic bird to prove their worth. Along the way, the three brothers are tested by various fantastical and magical trials in which their true characters and souls are revealed. Pedro, the oldest, turns out to be the most conniving, a scheming bastard who would not hesitate to throw his brothers under the carriage in order to claim victory. Diego, the middle son, is a namby-pamby fence-sitter, easily influenced by the darker-souled Pedro but can also take the right side on a good day. Juan, the youngest, is, of course, the kindest and has the purest of heart of the three.

After 1,034 stanzas (8 syllables per line, 4 lines per stanza), it is Juan who captures the magic bird that restores their father’s health (although Pedro, of course, claims credit for it). Along the way, they encounter various princesses and maidens who eventually become their wives; but not before the sibling rivalry really heats up and one brother turns against the other, fate and forgiveness intervene in one form or another, right triumphs, and the good and noble Juan rightfully inherits their father’s kingdom. (However, the title magic bird disappears midway and is nowhere to be found by story’s end.)

Various Filipino Feature Film Versions

Because the story lends itself to very cinematic storytelling, there have been several feature film versions from the Philippine film industry. The four most significant are:

The 1941 B&W version. On the eve of World War II, just a few months before the conflagration, a very young LVN Studios headed by Doña Narcisa de Leon (who provided the “L” in the LVN acronym; “V” was for the Villonco family who also owned the old Life Theater in Quiapo and “N” for the Navoa or Nabua family) marked its third anniversary that year by adapting the classic tale to film.

It starred Mila del Sol, Fred Cortes, and Ester Magalona and opened in October 1941, barely two brief months before World War II in the Pacific began on December 8, 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor and Manila. Of course, due to the sudden Japanese invasion, the film sank at the box office.

The poster from the 1941 film version, which was the first full-length treatment. (Image courtesy of Simon Santos, Video48)

Curious item about the 1941 production. The ad states the first screening at 8:00 a.m. There’s nothing like starting your day back then with a trek to Avenida Rizal before going to Divisoria.

Filipino film historian Simon Santos, in his Video46 blog, reports that “color” for a local film was attempted for the first time since the Philippine commercial film industry began in 1914. The “color,” however, was not through the use of actual color-negative but of positive prints (i.e., the celluloid actually used in the projection booths of the cinemas.) The color of the Adarna was painstakingly painted by hand frame by frame in the scenes with the bird. (The Philippines, still being a US colony in 1941, was not far behind mother-Hollywood, which only introduced full-color films with The Wizard of Oz in 1939.)

A few years ago, the Philippine National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) funded a full restoration of the 1941 Ibong Adarna. However, even in the restored print, one cannot see the pseudo-coloring attempt in the scenes with the bird. It can be viewed on YouTube wherein the film can be seen in its entirety in nine parts.

In a Newly Independent Philippines

World War II came and went, but it was not until 1955, in an independent Philippines, that a legitimate full-color version of Ang Ibong Adarna appeared. LVN came back, to celebrate its “17th Anniversary” with a new, lavish, and ambitious production. As the first full-length, full-color Filipino film, it was shot in Eastman Color, the Kodak Film Company’s answer to the rival Technicolor, Inc.

The 1955 remake starred one of the hottest film love duos at the time, Nida Blanca and Nestor de Villa. Filipino film wunderkind Manuel Conde returned to oversee the whole, full-color production.

Poster for the 1955 color remake. (This image courtesy of IMDB.com)

It is this film version, of which I, as an early movie-going child, have most fond memories. It cast a spell on a wide-eyed youngster. I remember seeing it in the so-called Cine Surot (the neighborhood flea-ridden cinema), which happened to be the Rainbow Theater near us, located in front of the San Juan Municipio.

Some of the film’s images have stayed with me through the years. One, a mountain “growing before one’s eyes” – obviously, it was a piece of fabric (maybe a rubber sheet or canvas) with some stage hands pushing it up from behind to make it look like it was “growing.” To a seven-year-old boy, that was utter magic. Another wonder was the multicolored bird whistling from a tree branch. They got the vivid colors right this time, but it looked phony to me because I had seen actual parrots and other exotic birds by then. Nonetheless, these were still enchanting images for an impressionable mind.

This scene I don’t remember: Nida Blanca and Nestor de Villa in their own “milk” bath scene, eight years before Liz Taylor had her own as “Cleopatra” in the million-dollar 1963 production. (Photo courtesy of Video48 and Simon Santos.)

For this article, I first reached out to Manuel Conde’s son, Jun Urbano, to find out if he had any extant material or memorabilia he could share of this 1955 version. Sadly, he didn’t have any. I also inquired at ABS-CBN (where I worked in 1969-71) because a few years ago, the network acquired the film library of LVN. Fifty years later, I no longer know anyone there, and even my efforts to find the right manager came to naught. Not even a courtesy reply was available from anyone at ABS-CBN-USA or in Manila.

In 1972 a third version, Ang Hiwaga ng Ibong Adarna (The Mystery of the Ibong Adarna), appeared. It is a “comic” version tailored to the comedic talents of Dolphy, Panchito, and Babalu, who play the three princes, now renamed Adolfo, Albano, and Alonso. The Ibong Adarna is embodied by actress Rosanna Ortiz. This is the “martial-law” version since the film was released in November 1972, a month-and-a-half after martial law was declared.

Ang Hiwaga ng Ibong Adarna (Image courtesy of Video 48)

Still a fourth version appeared in 2014, which brought full circle a hidden thread between three of the four film versions mentioned. It was the hand of master Filipino filmmaker, Manuel Conde (1915-1985). Conde had been a “technical adviser” in the 1941 version. He was then the director for the 1956 all-color version. Fifty-eight years later, in 2014, his son, Jun Urbano, took his own crack at the tale. (Conde was merely a stage name.)

Unlike the 1941 version, Urbano prefaced his 2014 take with “A commemoration of 100 years of Filipino film.” (So, the Filipino film industry started in 1914; just as World War I was starting in Europe.)

Urbano’s 2014 version was given a cogent review by Manila film critic Francis Joseph Cruz. An excerpt:

“Urbano’s ambitions are crystal clear. Ibong Adarna is meant to be children’s fare. It is supposed to be light and funny. Its darker moments are managed with jokes and pageantry. There’s nary an attempt to overreach or be subtle with more adult themes, since there are absolutely none.

“The movie is all about fun and fireworks . . . about spectacle and eye candy. The more it looks like a page out of an illustrated storybook, the better. Ibong Adarna is therefore heavily reliant on CG (computerized graphics). At its best, Ibong Adarna’s visual design is inspired. For example, the fearsome giant the tribesmen feed with their prisoners is ironically fashioned after Kuhol, Urbano’s diminutive sidekick in his television show Mongolian Barbecue.

“With Ibong Adarna, Urbano endeavors to enchant a new generation with the timeless fable. The modifications he introduces are mostly cosmetic, since there is absolutely no effort to update its mores and norms. The spirit remains almost the same.”

What’s quite interesting about all four film versions, considering its being a “European-set” story (or even going by the Chinese-inspired story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp), is that the various Filipino filmmakers chose to give the tale the visual trappings of a “Muslim”-set story. It appears to suffer from the “Aladdin-syndrome,” employing an Arabian/Moorish motif as if Aladdin and the Genie were hired as the costume and set designers. Is this strange juxtaposition possibly a reflection of the hybrid nature of what makes up contemporary Filipino culture?

A Phoenix or a Sarimanok?

A universal concept that the Ibong Adarna also takes after is the Phoenix, another avian idea of a bird rising out of the ashes of destruction, a resurgent creature which flames cannot vanquish. It carries the theme of regeneration. An inspiring example that comes to mind is Blaze, the mascot of the 1996 Paralympic Games in Atlanta. How could that not be in the mold of an Ibong Adarna, a restorative creature?

Blaze, the Phoenix mascot of the 1996 Paralympic Games. It looks very Ibong Adarna-ish to me.

There is still another Filipino magical, restorative, healing concept in the same vein -- the sarimanok, a magical rooster.

The “Sarimanok,” an off-shoot of the Ibong Adarna

And then there is Darna, an early Filipino super-heroine who began in Filipino komiks (graphic novel) in 1950. I believe Darna, a super-heroine in the mold of Wonder Woman (definitely not your shy, mahinhin, retiring Maria Clara-type), or at least the character’s name is inspired by Ibong Adarna.

World-famous illustrator Stanley Lau’s interpretation of Darna.

The Adarna on Stage and in Dance

Finally, last year, Ballet Manila presented the legend as a major, full-length ballet. Some scenes from the 2017 staging:

(Courtesy of Ballet Manila)

(Courtesy of Ballet Manila)

Soloist Abigail Oliviero plays the enchanted title bird (Courtesy of Ballet Manila).

At present, Ibong Adarna is an important Filipino literary classic being studied in freshman year in the Philippines, in accordance with the curriculum set by the Commission on Higher Education. Thus, countless high schools and colleges across the Philippines, stage their own productions of Ibong Adarna as a storytelling exercise, and the reader can sample and enjoy such proof of students’ attempts on YouTube.

So, is it a magical nightingale? The Phoenix? Darna? The sarimanok? Which one is it? The Ibong Adarna, I believe, is all of them—a generic “bird” of special beauty and unique healing powers. It’s a special something, that je ne sais quoi in each of us which, if we want something badly enough or want to turn something in us around, can be reached deep down in that well of determination. In other words, it’s that unique, special magic within each of us that we summon and draw upon sometimes in life to achieve a transformation, when the chakras open up and many answers in one’s universe are revealed.

So the Ibong Adarna resides in each of us all this time, just waiting to be hatched and released. The myth endures.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibong_Adarna

https://salirickandres.altervista.org/ibong-adarna/?doing_wp_cron=1518384812.4644899368286132812500

Professor Myke Gonzales, University of San Francisco

http://video48.blogspot.com/search?q=Ibong+Adarna

https://www.rappler.com/entertainment/movies/71099-ibong-adarna-pinoy-adventure-movie-review

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. His newest book, “Of Adobe, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles – An Anthology of Essays on the Filipino-American Experience and Some. . .”, features the best and brightest of the articles Myles has written thus far for this publication. The book is presently available on amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, Europe, and the UK).

Myles’ two other books are: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2016); and Thirty Years Later. . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes published last year, also available from amazon.com.

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH) for whose Journal he has had two articles published; a third one on the story of the Rio 2016 cauldrons, will appear in this month’s issue -- not available on amazon.

Finally, Myles has also completed his first full-length stage play, “23 Renoirs, 12 Picassos, . . . one Domenica”, which was given its first successful fully Staged Reading by the Playwright Center of San Francisco. The play is now available for professional production, and hopefully, a world premiere on the SF Bay Area stages.

For any enquiries on the above: contact razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia