The Gathering of the Storm Survivors

/(Seated L-R) The author, Chito Sta. Romana, Tony Pastelero, Charito Solis, Nelson Navarro, Gary Olivar and Jerry Barican in the back standing.

In January of 1990, as I was preparing to visit the Philippines from San Francisco, I inquired from my friend in Manila, Nelson Navarro, if there were any plans to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the First Quarter Storm (FQS). None, he said, but he thought it would be a great idea for the “storm survivors” to meet and reflect on the impact of that historical event on our lives, on the country and its future. We decided to reach out to our friends, on both sides of the FQS barricades, to gather together on January 30, 1990 in front of Malacañang.

This was what I wrote about our FQS reunion 33 years ago when I returned to San Francisco. Sadly, many of those who had gathered then have since passed away.

The “Storm” was triggered by the fraudulent presidential elections of November 1969 in which the incumbent unleashed his 3-G formula of Goons, Guns, and Gold to secure an unprecedented second term.

But while the public responded to this massive fraud with fatalistic resignation, the students were enraged. Throughout the Greater Manila area, student councils and related organizations gathered together in preparation for a massive protest rally in front of the Philippine Congress on its opening session.

The student rally led by the National Union of Students of the Philippines in front of Congress which started the First Quarter Storm. (Source: "UG: An Underground Tale" by Benjamin Pimentel)

On January 26,1970, more than 60,000 students amassed in front of Congress to listen to speeches describing what they believed to be the true state of the nation while Ferdinand Marcos gave his own self-serving version to his own choir of self-serving politicos inside.

After finishing his speech, Marcos quickly made his exit from Congress and, just as he was about to board the presidential limousine, a papier mâché crocodile (the symbol of political avarice) was hurled at his car. Instantly, the phalanx of government soldiers charged the rank of the assembled throng swinging their rattan truncheons and bashing the heads of the helpless students. Hundreds were seriously injured as the whole nation watched the tumult live on their TV screens.

The January 26 police riot in Congress led to the January 30 March to Malacañang where thousands of students surrounded the fortified palace. That was the moment when suddenly, the lights went off and the eerie silence of darkness became deafening.

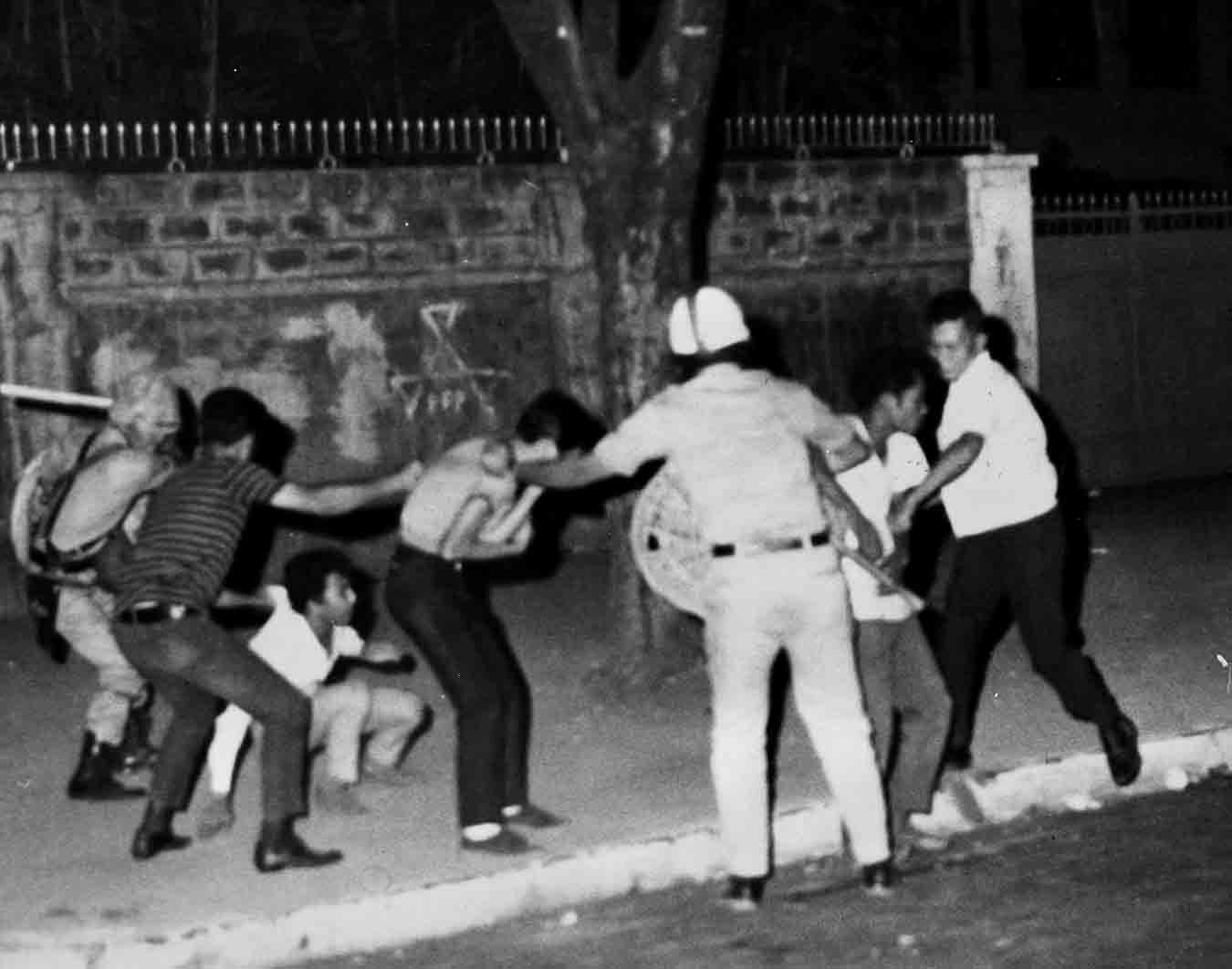

Protestors storm malacañang gates on January 30, 1970 (Source: FQS Library)

The riot police defending the palace retreated into the night only to be replaced by battle-hardened field soldiers armed with high-powered Armalite rifles out to quell a rebellion. Before that long dark night was over, four students lay dead, scores paralyzed, and hundreds maimed from gunshot wounds.

As Mario Taguiwalo recounts it, “The death of friends. The terror of gunfire, the taste of a truncheon taught a lot of ‘isms’ in one night. By the morning of Jan. 31,1970, a thousand chapters of student organizations had begun taking root in schools and communities nationwide.”

Riot Police arresting protestors outside Malacañang (Source: FQS Library)

Our 20th Anniversary Reunion

On the 20th anniversary of that historic day, I found myself at Freedom Park in front of Malacañang, the scene of that pitch dark battle between unarmed students and fully armed soldiers. There were simple ceremonies to mark the occasion and a small cast of notables from that period gathered together to remember.

There was Jerry Barican, then the radical president of the UP Student Council and now a conservative lawyer and businessman. Jerry rationalized his political transformation by quoting from Churchill:” If you’re not a radical by the age of 18, you have no heart. If you’re still a radical by the age of 30. You have no head.”

There, too, was Nelson Navarro, then the articulate spokesman of the student coalition, now an acerbic columnist and political analyst. Mario Taguiwalo was present too – once a pillar of student mass action, now Cory’s Undersecretary of Health. Also present was Diggoy Fernandez, who was a radical student from the elite La Salle College, now a wealthy banker and adviser to the Philippine Aid Plan (PAP). Ma-an Hontiveros read the Manifesto we prepared for that event. She was then a curious colegiala from St. Scholastica’s College, now a well-known TV personality and the owner of her own communications company.

We were reunited with John Osmeña, then a freshman congressman and a supporter of the students, presently a distinguished senator from the booming province of Cebu. Dr. Nemesio Prudente also attended our reunion. He was then and now president of the Philippine College of Commerce (PCC) now renamed the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP). “Doc” has survived several assasination attempts from rightist death squads since 1986.

There, too, but feeling a bit out of place was Gen. Rafael “Rocky” Ileto, then the Commanding General of the Army with responsibility for the defense of the palace, now the National Security Adviser of President Aquino. “We were on opposite sides of the gate then.” He said, “but now we’re on the same side.”

And then there was me, once a fledgling nationalist eager to change the world, now a practicing California attorney and president of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission.

Not there but present in the manifesto he had drafted and faxed from New York was Gary Olivar, then the boy wonder of the radicals, now a vice-president of Sumitomo Bank with a Harvard MBA diploma on his wall.

The Compelling Dream

In his Manifesto, Gary reflected on how “a singular dream moved a generation”,

“A dream so compelling in its inception, so irresistible in its sweep that it hurled thousands of us against the wall of this palace – as if somehow through the sheer weight of our passions on that endless night, we would reclaim the palace for our own.”

Gary mirrored our sentiments when he declared that “in the conceit of our youth.” We believed we could “repair the broken bones of a people long despoiled and fulfill a dream of human freedom of national sovereignty, or equitable progress for every Filipino.”

Those present in the simple rites were now 20 years older, at least 20 pounds heavier, reeking of the respectable air of the very Establishment we had once hoped to change. Except for the general and the TV lady, the cast exhibited prosperous tummies and shy graying hairlines. The authoritative mien of the bourgeois had replaced the lean and hungry look that was the activist trademark. The future had arrived, tomorrow had lapsed into today, so how had we fared?

We came together to share a collective memory of an era gone by. One simply could not have been part of that Storm and not be affected by its sweeping fervor and the surge of nationalist ideals. But the stark realities of a grown family and coping with our economic needs conspired to set aside the Utopian dreams and like gravity bring us back down to earth.

Mario the Undersecretary reflected about the “gem” of the First Quarter Storm: “Every time I am tempted to give up on people, I am reminded of the utter power of ideals deeply held and I persevere again in seeking to convince not compel. I recall the sense of community in the whole and the sense of helplessness in the chaos, and I realize again that futility of solitary happiness in the midst of widespread misery.”

“As I raise my children, I remind them of our honorable past. Of the vast reservoir of common sentiment that drive violators, trip cutters, lane jumpers, and other unsavory characters among us.”

Mario spoke for all of us when he wrote about the values the experience left in him:

“The courage to stand by one’s principles, the desire to freely express one’s dream for the nation, the willingness to pay the price, the eagerness to depend on one’s fellowman, the exhilaration of finding new ones.”

The First Quarter Storm, for those who lived through it, was not just a historical event. “It has become an attitude,” insists Mario, “a part of a value system that colors one’s view of society, a powerful memory that sparks one’s hopes for a possible Philippines. These things are important in protesting the evils in our midst as they are invaluable in affirming the good around us.”

The most poignant part of the ceremony was the moment of prayer offered to the memory of those who died that fateful night and in the many years since then. Ma-an expressed our common responsibility never to forget. “To them we owe the broadest appreciation of their heroism – whatever their particular vision of the future, however they chose to fight on its behalf whenever they were taken from us.”

At the ceremony’s conclusion, we embraced each other firmly and with moist eyes. “Reunions are beautiful,” Nelson mused “because the older we get, the more we cease seeing ourselves as friends or enemies,” he said. “We are simply survivors sharing a common memory.”

“One simply could not have been part of that Storm and not be affected by its sweeping fervor and the surge of nationalist ideals.”

Where Are They Now? 1/16/2023

Nelson Navarro saw me off at the Manila International Airport when I left for the US in 1971. Later that year, I saw him again in San Francisco when he moved to the US to study at UC Berkeley just before Marcos ordered his arrest after the Plaza Miranda bombing in August of 1971. The arrest warrant formed the basis for the political asylum Nelson applied for and was granted, for which he received his green card. In New York, he graduated with a master's degree in international affairs at Columbia University in 1976.

Nelson Navarro (Source: ABS-CBN News)

In his memoir "The Half- Remembered Past", Nelson reflected on his activist experience "FQS turned me into an exile. It forced me to the kind of life I wanted — to remain true to my values and to be a man of the 20th and 21st centuries. I was a concerned individual who would fight for a good cause, but who also loved life. (In America), I fell in love with music and literature. For the first time, I was free.” Nelson Navarro died of a stroke in 2019, a day after the 47th anniversary of martial law. He was 71.

I was not Nelson’s closest friend. That honor belonged to Jerry Barican, who was chair of the University of the Philippines (UP) Student Council and a leader of the activist Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK) when the First Quarter Storm broke out in 1970. Jerry was arrested by the military upon the declaration of martial law by Marcos in September 1972. After his release, Jerry ran for the Senate together with former Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. in the opposition Laban Party in 1978. In an ironic twist, Jerry ran again for the Senate in 1992, but this time with the Nationalist People’s Coalition party of Eduardo Cojuangco, a staunch Marcos ally.

Jerry obtained his law degree from UP, then went on to Harvard Law School for his Master of Law in 1979. In 1998, Jerry was appointed presidential spokesperson of President Joseph Estrada. He was also appointed to the board of the Development Bank of the Philippines, where he served until the term of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. On October 5, 2014, Jerry died of a stroke at age 66.

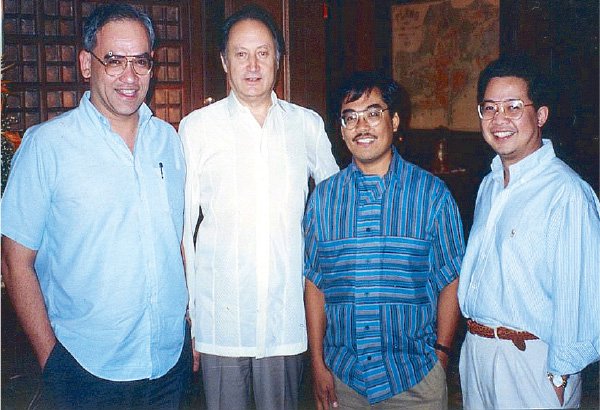

After the fall of Marcos, Jerry Barican, Nelson Navarro and Ray Altarejos go out to lunch with the USSR Ambassador (second from left) at the Peninsula Manila. (Source: philstar.com)

Gary Olivar was one of my best friends in high school when he lived just a block away from my home in Quezon City and he attended UP High School while I was a student at nearby Philippine Science High School. He invited me to speak at the rally in front of the Philippine Congress on January 26, 1970 as president of the National Union of High School Students. It was my introduction to the FQS.

Gary was one of the first student activists to be arrested when Marcos declared martial law on September 22, 1972. After his release a few years later, Gary returned to UP and earned his MA from the U.P. School of Economics and he later obtained his MBA from Harvard Business School. When he returned to the Philippines, he accepted a post as economic spokesman of the Arroyo administration. He died of a heart attack on June 29, 2021 at age 68.

Mario T. Taguiwalo was a schoolmate at the Philippine Science High School where he wrote the school’s official anthem while still a student there. He married his high school sweetheart, Beulah Pedregosa who, like Mario, was also a gifted writer. During one rally in Manila’s Plaza Miranda, Mario and I were picked up by uniformed officers in a police jeep. When Mario was asked his name, he replied “Romeo Milan, sir,” the name of classmate he did not care for. Luckily, we were released without charges being filed against us that night. Unfortunately, Mario was later arrested when martial law was declared in 1972.

When People Power swept Cory Aquino to the presidency in 1986, Cory appointed Mario as her Undersecretary of Health. Of Mario, filmmaker Howie Severino wrote: “I was constantly amazed at what Mario could do. He could ghost-write eloquent speeches quickly in both English and Filipino, he argued persuasively, he thought strategically, he cracked jokes at just the right time, breaking any tension with that exuberant laugh. His stamina for work was legendary. He gained a reputation as a whiz in the Aquino administration. He was the right-hand man of the equally brilliant [Dr. Alran] Bengzon in nearly every major health initiative of that era, including the ground-breaking Generics Act that changed the way doctors prescribed medicines, and the Milk Code, which promoted breastfeeding and introduced reforms in the distribution of infant formula.”

Mario Taguiwalo (Source: Rappler)

Mario died of colon cancer on April 22, 2012 at age 62. Beaulah shared a note that Mario had written in his final days: “I wish all of my family, friends, and colleagues to know that I only have the fondest memories and deepest gratitude and affection for them. May they find comfort and joy in gathering together wherever they are, whenever they can, to celebrate my life instead of mourning my passing. May they speak of me and what I have done with fondness, and may they continue to build on the fine ideas and good works that we, together, were privileged to be part of. Most of all, I wish and pray that my family, friends, and colleagues lovingly embrace, comfort, protect, respect, and support my beloved wife, Beaulah, and my beloved son, Homer…With God’s grace and mercy, they will have to continue living their lives here on earth until it is time for them to join me and my sons Mike and Mark in our final and eternal heavenly home.”

Rest in peace, Nelson, Jerry, Gary and Mario.

Rodel Rodis taught Philippine History at San Francisco State University when martial law was declared and would later serve as Secretary-General of the NCRCLP. Send comments to Rodel50@aol.com or mail them to the Law Offices of Rodel Rodis at 2429 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94127 or call 415-334-7800.

More articles from Rodel Rodis