The Filipino Art of Naming Food

/Bulachoy

I tried the dish but didn’t like it that much – ditto with “buko batchoy,” another variant of batchoy, served with strips of coconut meat. Guess I am too much of a La Paz batchoy purist! But the inviting poster got me thinking about two favorite pastimes: food and wordplay.

La Paz Batchoy (Photo by Vic Salas)

Filipinos in general (and savvy marketers, out to catch the first interesting sound byte) have this inordinate talent for naming things, punning, and wordplay. I think this may be because we Pinoys have a very mixed cultural and linguistic heritage, with our language peppered with words from other countries and cultures, whether from Spain, the US, China, Indonesia, and Malaysia, not to mention our own indigenous 80-something languages and their dialects. Hence, the Philippines is fertile ground for puns and doublespeak, abbreviations, and combinations of words and phrases that are catchy, melodious, memorable, and provide humor and/or innuendo.

Since we’re talking about food, we have tapsilog, tosilog, longsilog. The first time I heard these words was in the early ‘80s when a humble food stall -- styled like the early “burger machine” stalls, serving garlic fried rice, an egg fried sunny side up, and either tapa, tocino or longganisa -- was set up in the Ermita area. It would also add bits of pickles from green papaya (atchara) on the side, with a dip of soy sauce, vinegar and kalamansi (Philippine lemon). It was open late, so with fellow resident physicians from Philippine General Hospital who were bored with the cafeteria food, we would saunter over for a quick, filling meal. In a few years, joints serving these dishes would pop up all over the country and become as popular as hot pan de sal.

Soon, daing na bangus and danggit would also make it to the menu, as would corned beef, slices of ham, Spam, etc. And, of course, these were just called “hamsilog” “bangsilog,” “spamsilog,” etc. During the later years of Marcos, with inflation spiraling and people had to make do with eating parts of chickens they would not normally gnaw on, grilled chicken bits such as “Adidas” (chicken feet) “IUD” (chicken intestines and entrails) and “helmet” (chicken heads) became regular sidewalk fare. Other bits and pieces of pork made it to the “sumsuman” (food typically for accompanying alcoholic drinks) table, including sisig, of Pampanga origin and made from pig’s snouts and other bits that were not used in the commissaries in the U.S. bases, all spiced and tarted up on a sizzling plate. Later, the pig’s head bits came to be known as “maskara” (“mask”), perhaps owing to the look of the flesh stripped from the skull.

There is a story of how “crispy pata” came to be, as a way of salvaging pig’s feet and knuckles that were often left untouched from the popular lechon. However, the Germans may have beaten the Pinoys to this, with their pork knuckles and sauerkraut; but even in several restaurants abroad, I’ve often seen “crispy pata” on the menu, rather than “deep fried pork knuckles.” Must be the Pinoy diaspora, rather than Germany, that has made this a staple.

On the subject of naming food, I don’t think there is any other city in the archipelago that has evolved more food or distinctive dishes with their place names indicated, than Iloilo. There is, of course, “pancit Molo” (also known as sopas de Molo), “La Paz batchoy,” (both of partly Chinese origin) and cookies and pastries from the “Panaderia de Molo,” operating since 1872 and one of the oldest bakeries in the country. The more recent 1980s-era “biscocho de Jaro” is now known to Filipinos everywhere. Barquillos de Iloilo, though Spanish in origin, is also associated with Iloilo, particularly Deocampo’s, which has been doing this rolled thin wafers for over 125 years.

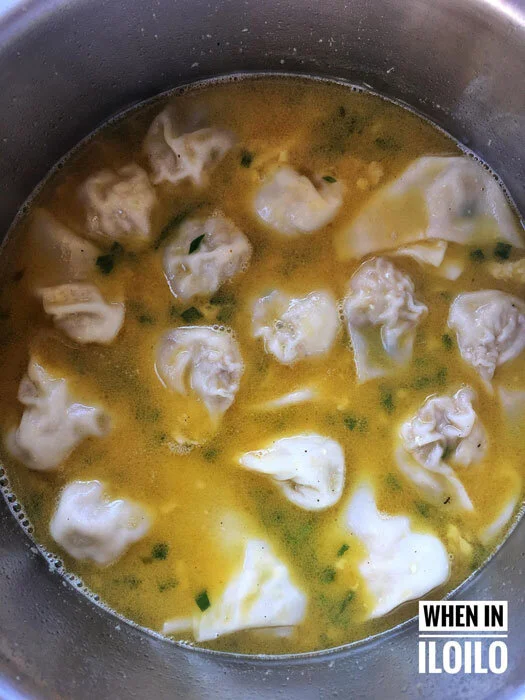

Pancit Molo (Source: When In Iloilo facebook page)

Naming food after the places of origin is an established practice. For example, “pancit ng taga-Canton” has become “pancit Canton,” and ditto with pancit Malabon, and puto Manapla. Pinoys have also been known to christen some dishes with names of places, perhaps as a marketing ploy – for there is no chorizo de Bilbao in Bilbao, Spain; no Mongolian barbecue in Mongolia, and neither is there lumpia Shanghai in Shanghai. I doubt if the descendants of Chinese patriot Sun Yat Sen know that there is a pancit here named after their illustrious ancestor.

There is also the use of jargon or initials for naming food, for example, “KBL” for kadios-baboy-langka, (black eyed peas-pork-jackfruit) another popular dish of Ilonggo origin. Or “CPA” for Chicken Pork Adobo. Part of the catchy names here is that the acronyms have other meanings in the Philippine context – “KBL” was a political party during the dictatorship years, while “CPA” is an abbreviation for certified public accountant.

Another way of naming food, especially pastries, would be to shape them in unusual ways, and name them in unforgettable ways – for example, pan de monay because it is shaped like a woman’s private part, or monay. “Lubid-lubid” is the crispy cookie dough that’s shaped like a twist of rope, or “lubid”; or the bread called “teren-teren” (probably after its shape, which is like a series of miniature railroad cars). I still can’t figure out though why glutinous rice patties with grated coconut, brown sugar, and sesame seeds came to be called “Inday-Inday.” Or why that delicious combination of glutinous rice and young coconut, bought along the highway in Pavia, Iloilo is called “baye-baye,” from “babae” (female). Is there a gender thing there somewhere?

Leandro Romero, at the Original Deocampo Barquillos (Source: facebook)

There may also be some racist undertones that we may not always recognize, as when bread with a pasty yellow filling, is called “tutuli sang intsik” (“Chinese earwax”). As a kid, I used to believe that, but it did nothing to reduce my appetite for the colorful bread as an afternoon snack, though it did instill visions of people cleaning their ears and massing the earwax into the dough! And I wonder who first coined the word “bakareta” to indicate beef in caldereta, when “kalderetang baka” would do just as well? Or do they mean, baka caldereta (maybe it is caldereta)?

And then, in a class by itself, there is the 16-21-day-old aborted duck embryo, known as “balut,” and a variant, called “penoy,” both of which are purportedly of Chinese origin. The name comes from the Tagalog word, “balot” meaning, “wrapped.” Literally the developing embryo is still wrapped in the egg white (“balut sa puti”) and the membranes when hard-boiled and eaten. When the cooked penoy eggs are dipped in an orangey batter then deep fried, they are called “kwek-kwek” (or quack-quack), after the sound ducks make.

But the naming also extends to drinks, and I see lots of these puns in use to name places that serve tea. Not the traditional Chinese or Sri Lankan or British teas, but those concoctions loaded with syrup, milk, tapioca, and various other additives, popular with teens and millennials. Here in Iloilo, I’ve seen “TEAlawi” (try it); “Ma-arTEA,” “arTEAhan” and “ynarTEA” (being picky or finicky), “Lilin-TEAhan (an ilonggo swear word, “linti” or may lightning strike you) “tas-TEA,” “TEA-licious,” and in a salute to the Covid era, “QuaranTEA,” no doubt inspired by quarantine.

Since we’re on the subject of naming dishes for easy recall, how about “bulog” (bulalo with itlog, or egg); diputa (dinuguan, puto, and taho or ginger drink)? For the non-Pinoy speakers, “bulog” also means “bald,” while diputa is an ilongo cuss word, short for the Spanish hijo de puta” or “son of a whore.”

Kaon ta! (Let’s eat!)

https://journalofethnicfoods.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42779-019-0020-8

Dr. Vicente Salas is a retired public health specialist who has worked for the UN and International NGOs in over 15 countries. He is now back in his native iloilo, after being away for 35 of the last 37 years.

More from Vicente Salas