Sumptuous Fil-Am Fiction, Roots and All

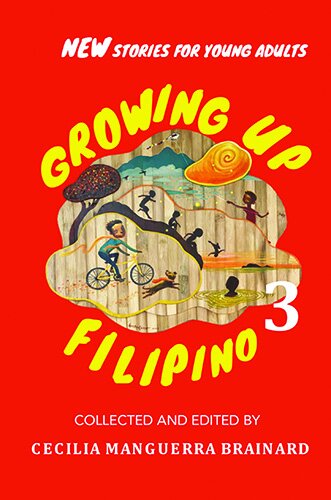

/Book Review: Growing Up Filipino 3, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, ed. PALH, 2022.

The numinous has a manifestation in the volume's concluding story, “Babaylan in Playland by the Sea” by Oscar Peñaranda. Amador, the male protagonist, is on a double date with Maria, named after the legendary lovely maiden who supposedly lived in Mount Makiling in Los Baños. In her capacity as a babaylan (shaman or priestess), she tells Amador, “You're the gifted one.”

Oscar Peñaranda, author of "Babylan in Playland by the Sea"

After he says “No one is interested in reading about Filipinos, especially Filipinos.” she turns her hands palms up and prophesies, “Through these soft hands, your gift will flow.” The Growing Up Filipino series dispels Amador's concern and verifies Maria's prediction.

Forethought, not happenstance, has determined the order in which stories appear in Volume 3, as the placement of Peñaranda's story shows. Again, Patricia Manuel's “Pig” and Mig Bravo Dutt's “Becoming Victoria,” stories 10 and 11, are opposites in almost every aspect: family dynamics, diction, endings, and tone. In “Pig” the “family” could hardly be less integral. The mother has left; the father occupies a separate house and stays away most of the time, leaving two brothers to live with only a yaya (nursemaid). The story is rendered with a liberal dose of colloquialism (e.g., “gonna,” “dude,” “chillax”), profanity and obscenity, memes (e.g., “IRL” and “WTF,” the latter also an example of the immediately preceding category.) “Pig” ends with the brothers, accompanied by the yaya, leaving the house permanently. The tone is high-volume, flamboyant, pull no punches.

Mig Bravo Dutt, author of "Becoming Victoria"

In contrast, “Becoming Victoria” validates traditional Filipino values, especially extended family solidarity, respect for elders, and putting a premium on education. The diction is G-rated; no one need have qualms about children reading it. The protagonist, Toyang, learns from the downfall of the flashy Cordovas, with their big house, exquisite furnishings, expensive clothes and jewels, that all that glitters is not gold. The Cordovas leave town suddenly, Señor Cordova under a cloud of suspicion of having committed estafa (fraud). The Cordova's house is taken over by Uncle Andy and Auntie Julie, unpretentious, humble people who put on no airs or expensive clothes or jewelry. They redo the Cordova house in a plain, practical manner. The tone of this story is muted--even-keeled and placid--in keeping with its plot.

Patricia Manuel, author of "Pig"

The stories in Growing Up Filipino 3, as is the case in Volumes One and Two, are diverse in several senses. Most conspicuously, the settings vary from Philippine locales such as Manila, Negros, Cebu, and Leyte to U.S. locales, especially southern and northern California, and in one case (“Narisa” by Marianne Villanueva) Siem Reap, Cambodia, as well as urban, suburban, and rural areas. Within these confines, as Brainard notes in her “Introduction” to the volume, “The class system in the Philippines is evident in many stories… These stories reveal Filipino and Filipino American mores, culture, history, society, politics, and other nuances. For instance, Filipino respect for elders, extended families, religious practices, funereal rites, love for folklore.... Politics and history, even though in the background, are inherent in many stories.”

The almost diasporic resonance of these stories may make us wonder whether there will be a Growing Up Filipino 4 with selections written, in Eric Gamalinda's words in his introduction to Flippin': Filipinos on America,“... in the archipelago, in Australia, in Europe and America, by people who have never seen America, people who have never seen The Philippines, or people who have seen one or both” ... (cited from Davis' “Introduction” to volume one, x). We might like to expand “America” to “the Americas” to include Filipino Canadians and Filipino Hispanics and Latinos and add to these possibilities Filipinos from other Asian countries and the Pacific region.

Growing Up Filipino 3 is admirably diverse in other respects, such as the stories' points of view. In the leadoff story, “Tall Woman from Leyte” by Gina Apostol, the narrator, a six-year-old (“almost seven”) girl, provides innocent but devastating depictions of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos, which would be boffo comedy were it not for the brutal and lethal crimes of the former President and first lady Imelda. “She was beautiful. She sparkled in the sunlight. Gold was on her arms, jewels on her fingers. Diamonds, green stones, a ruby. She seemed all dressed for mahjong. But most wondrous of all were her shoes: white large stones were embedded on the tip and sides: diamonds, diamonds on her shoes, so close to the earth they glittered like the quartz I sometimes found on the beach.”

“She was the queen of minerals.”

Ferdinand fares no better: “His hair was wonderfully slicked back, like a dolphin's sleek watered flesh...he...looked like something ready for creative taxidermy: his skin was all red and taut, stretched as stuffed animals should be.” But the external glitz masks an inner vacuousness. At lunch the six-year-old rearranges the coasters on the mats so that the capital cities correctly align with their respective provinces. Imelda traces her family lineage to “Martin de Legaspi,” which our narrator corrects to “Miguel de Legaspi.” Imelda tries to recoup her gaffe: “See, look at the children we are bringing up! The children of the New Society! Knowledgeable and respectful and speaking English fluently as a second language! What more can this country want? What more can the people ask for?”

In Nikki Alfar's “Lola Ging and the Crispa Redmanizers,” the title character is not really the narrator's grandmother, but “a distant cousin of my mother's late mother.” Nonetheless, when the narrator's mother gives birth to twins, Lola Ging comes to help out, since the household now has four preschoolers. Lola Ging is quite the character. She is a Philippine Basketball Association fanatic, to the extent that she is delighted with the narrator's birth: “We will have a full team.” She forbids the consumption of eggs by the children because the “Holy Spirit” had informed her that the eggs' oval shape would result in school scores of zero. Lola Ging has “the fire of multipurpose pagan/shaman/Christian conviction.” She certainly hedges her bets. When Lola Ging dies, at age 94, the comic tone shifts to wistful, though not quite plangent: the shells of the watermelon seeds, which she ate in prodigious quantities, “drift gently...light as a whispered prayer.” The tonal shifting and recollections about Lola Ging are facilitated by the now-adult narrator not only recounting, but also assessing her memories, a point of view that paints a markedly different but equally effective picture from that produced by the six-year-old in “Tall Woman from Leyte,” e.g., “Reincarnation was hardly a tenet of Roman Catholic doctrine...”

Brainard's “The Dead Boy” also has a retrospective point of view, but the adult narrator looks back only to adolescence, not childhood. The predominant motif is the infusion of death into the lives of the characters. The dead boy of the story's title, Bill Lowry, has been murdered. The then-14-year-old narrator and her friend Mildred giggle over their teenage infatuations (The narrator's being Bill) and mutter “...too bad he's dead. We didn’t say much else.” Death has been so prevalent-- Bill's death, her father's death, her grandmother’s death, even the sparrow’s death--that the girls have become inured to it.

The third person point of view in the following story, George Gonzaga Dioso's “The Child,” peers at death in the opposite direction. The physical death is that of Angelica, a girl about six years old. Her name is clearly symbolic. In church she wears a white dress; her name is also that of a plant with clusters of white or greenish flowers. She has a warm smile, and when the protagonist, Sylvia, takes the dead child's hand, it is ice cold, but “the clouds had cleared and made way for the bright stars above the steeples. There was now a certain warmth in the lights that flooded from the open doorway.” She is an angel.

The contrast to Max and Sylvia's son, Jet, who has, in young adulthood, turned into a liar, thief, degenerate, and perhaps even devil, is complete. This polarization is not due to cause and effect. The little girl's parents have tried desperately to raise the money for the hospital treatments to try to cure their daughter's chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Max and Sylvia have made major financial sacrifices so that Jet could have the best education. The polarization is also not attributable to a Manichean universe, not explicable as simply the way things are. Instead, as Deoso explains in the supplementary paragraph preceding the story, one purpose of the Philippine ghost story is to explain “a certain phenomenon.” The explanation, though, cannot be discovered by ratiocination. This is why the events of the story are excruciating for the adults involved and tensely gripping for the readers. The one given is the mother's psychological substitution of the dead girl for Jet, living in body but dead in soul, evidenced by the fact that Sylvia is the only one who can see the dead girl.

Obviously, none of the stories discussed so far fall into the Bildungsroman tradition (well encapsulated by Rocio G. Davis on pp. xi-xii in her “Introduction” to the first volume of Growing Up Filipino. Stories like Ian Rosales Casocot's “The Rubber Duckie Confessions,” James M. Fajarito's “The Goat,” and Angelo R. Lacuesta's “Nilda” are within that tradition. In Casocot's story and Fajarito's story, mild angst in terms of mental coming to terms is the predominant tone; Lacuesta's story is imbued with the physical coming of age reactions of an adolescent mentored (in the ancient Greek sense) by his yaya.

Each of the stories in Growing Up Filipino 3 has a different author, which provides readers with the greatest possible breadth of voices, techniques, and perspectives. However, followers of the series of volumes will note that stories from Casper, Montes, and Peña appear in two volumes and that stories from Villanueva, Roley, Brainard, and Peñaranda are present in all three. This carryover, though, does not diminish the variety that each volume offers.

As an example of the former category, Casper's “In Place of Trees” in Volume One is set in the immediate aftermath of WWII in Manila, with desolation represented by the colonel trying to get compensation for soldiers who had served but had not been recognized officially, and the senseless death of the narrator's brother Justo, the victim of stray shrapnel falling into the narrator's yard. “Happy” in Volume Three is nothing like this or any of the other stories in the The Secret Runner (Florentino, 1974), the Casper collection in which this story appears.

Velvet, the protagonist of “Happy,” has just months ago moved from San Francisco to Sausalito. Her parents have died in a car accident. The tension that runs throughout “In Place of Trees” is in “Happy” replaced by a disengaged stasis. Velvet works only four days a week in a shop selling vases, and in her apartment she sits painting her toes and listening to her radio, which she calls “Happy.” She sits all day by her window...” At work she will “stand beside vases taller than herself, drawing stares with her silence,” a depiction redolent of the “museum world” of Henry James. The prose style accentuates the effect. Sentences like “She is weeding out all memories from her life, fighting them when they come unbidden while she stands, darker than the bark of redwood, shimmering inside a caftan beside a vase slashed across by stones that mimic riverbeds dried out by summer” induce reader somnolence with their rhythmic hypnotism.

Peñaranda's work is the clearest example of breadth of vision amongst the writers represented in all three volumes. The title of the genteel tale “Babaylan in Playland by the Sea” suggests a children's fantasy. It is not quite that; it certainly is no set piece for, say, “Peter Pan,” but it is gentle and soothing.

The title “Day of the Butterfly” in Volume One may seem to denote a similar approach, but it is anything except that. In it a group of Filipino field workers hitchhiking along a dusty, hot highway (of Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath perhaps) are passed by a Cadillac full of blond football players, who are given an erect middle finger for their attitude. The Cadillac returns, and one of its occupants accosts Batok, one of the field workers who live hardscrabble lives. In mid-lunge, the blond assailant is deterred by a balisong (butterfly knife made in Batangas) that Batok wields. Implausibly, the field workers and the Cadillac passengers bond, to the degree that the Cadillac takes the field workers to their next job. The stark, potentially ugly aspects of the story, set in 1962, surface in the understated but underlying racist implications of the respective descriptions of the field hands and the football players, (evoking, perhaps Bulosan's America Is in the Heart) and the looming cloud of the Vietnam War.

“The Price,” Peñaranda's contribution to the second volume, is set entirely in the environs of Tacloban. The narrator's Uncle Andres clings stubbornly and desperately to the traditional ways of life. He drives a karomata (one-horse cart), not a motor vehicle. “He spoke the national tongue with a thick provincial accent.” He is so attached to his land that he refuses to sell it to the Community Board

for development even though it is, in the words of the narrator's father, “stretched out, thin-layered, scale-cracked earth.” Uncle Andres responds that “this is the land of our ancestors.... It is not ours to sell.” On a personal note, Andres says “...I am childless...and wifeless... and homeless. I grow old. Things left to hang on to are getting fewer and fewer...” Uncle Andres and his nephew attempt to till the land, but nothing grows. The story is plaintive, very different in nearly every respect from “Babaylan in Playland by the Sea” and “Day of the Butterfly.”

As with Volumes One and Two, the stories in Growing Up Filipino 3 are not only for young adults. Roger N. Buckley noted about Volume One, “Despite the book's subtitle, this is also a book for adults,” and as Brainard herself averred in her “Preface” to Volume Two, “The stories in this collection...can be enjoyed by anyone, regardless of age” (ix). “Anyone” also extends to non-Filipinos. The themes, plots, characterizations, characters' motives and aspirations, settings, and circumstances are universal. The value of these stories is equally available to anyone who can read English and appreciates outstanding literary achievement.

In this regard, the absence of a Volume One feature is a loss for Volumes Two and Three: The Glossary of Words and Phrases, especially since the Glossary identified the language (Tagalog, Bisayan, Spanish) of any non-English locution that appears in any story. Perhaps the Glossary was discontinued because by 2010, when Volume Two was published, virtually everyone had access to Google. However, the Glossary makes Volume One self-contained. If internet access is not available or handy, the reading experience is not disrupted.

Beyond that, the apparatus in the Growing Up Filipino series is an appreciated plus. Each volume has a preface and /or introduction, helping readers to contextualize the contents. For each story, all three volumes have a one -to two-paragraph biography of each author as well as the editor. Volume One and Volume Three present a preceding informational snippet about a relevant element of each story. These pieces are excellent stage setters. For example, Migs Bravo Dutt's “Becoming Victoria” is preceded by a paragraph explaining the ritual of house blessing. Nikki Alfar's “Lola Ging and the Crispa Redmanizers” is prefaced by three paragraphs recounting the history of basketball in the Philippines and the success of Philippine national teams in major international competitions. The layout of the biographical and informational features has been upgraded, the single column format in Volume Three superseding the double column format in Volume One, resulting in significantly enhanced visual appeal.

In sum, Growing Up Filipino 3 is excellent. It should be in the collection of every public and college/university library and is a must-have acquisition for individuals who deeply value Philippine literature.

Lynn M. Grow has a B.A. in English and Philosophy, an M.A. in English, M.A. in Philosophy, and PhD. in English, from the University of Southern California. His specialty is Philippine literature in English.

Growing Up Filipino 3: New Stories for Young Adults is available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and palhbooks.com. The earlier volumes of the Growing Up Filipino series (Growing Up Filipino: Stories for Young Adults, and Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults) are also available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and palhbooks.com. All three volumes are published in the US by PALH (Philippine American Literary House). The Philippine edition of Growing Up Filipino 3 is scheduled for release by the University of Santo Tomas Publishing House in December 2022."