Ricky Lee’s Life Is The Stuff Of Cinema-Verite

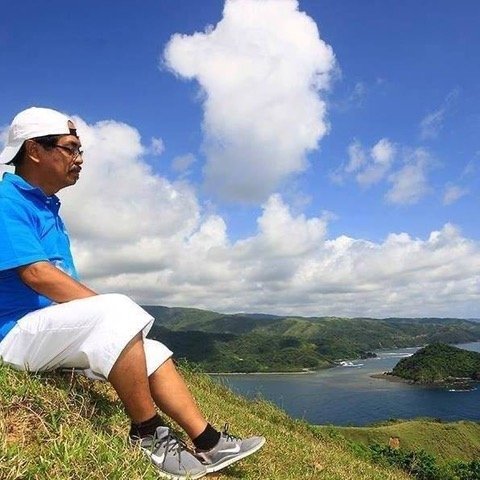

/Ricky Lee as National Artist for Film. (Photo by Arjanmar Rebeta)

His films (Himala, Moral, Jose Rizal, Jaguar, Sa Kuko ng Agila, The Flor Contemplacion Story and many others) were watched by millions.

He has fathered hundreds of film workshops that gave birth to a new generation of filmmakers and screenwriters.

On top of that, he has written distinguished screenplays, short stories, novels. He is a keeper of countless awards and life achievement citations.

A closer look at his own life story is even more remarkable.

Ricky Lee with Marilou Diaz-Abaya and filmmaker Keith Sicat. (Photo: Sari Dalena)

Born in Daet, Camarines Norte in March 1948, Lee led a motherless life since age five and hardly saw his father. In high school, he studied hard to get class honors and mainly to fight what he admitted was his own inferiority complex.

In high school, he wrote his first published short story (“Mayon”) for the Philippines Free Press, stayed with kind neighbors and left for the big city after graduation. He had worked menial jobs, endured hunger many times over, but never left writing.

As I rewind his present life swamped with hundreds of citations from schools and award-giving bodies and getting the highest honor – the National Artist for Film and Broadcast Arts – from no less than the government which made his life miserable during the martial law era, I realize Ricky Lee’s life is the stuff of cinema-verité.

Indeed, the way he confronted life is the stuff of “truthful cinema” with true-to-life camera lingering on his personal journey “to unveil truth or highlight subject hidden from reality.”

And yet he didn’t attempt to hide his past even as he was deluged with awards at this late stage of his writing life.

Scene from the CCP awarding night highlighting achievements of Ricky Lee.

Addressing the 2019 graduates of Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP) which awarded him a degree of Doctor of Humanities honoris causa, Lee admitted he learned so much from life but didn’t ignore the value of education.

Education is important to me, he opened his graduation speech in Pilipino.

Then he unveiled his life story as truthfully as he could.

Almost like a page from one of his award-winning screenplays.

After finishing high school in Daet town, he left the family who took care of him; they could no longer afford to give him a college education.

He went to the big city with four other friends.

Like my late daughter, he studied at UP Diliman but didn’t finish the course. He joined a movement. It was the time to fight for a cause he personally believed in.

It came with a price. He along with another writer friend (and also future national artist) were incarcerated and spent more than a year in detention.

Yes, his dream even as a child was to teach.

But he couldn’t as he needed a college degree.

No way that could stop him from teaching.

In 1982, he started offering screenwriting workshops for free for future filmmakers.

After four decades, he gave birth to a new generation of film writers.

Said one Jenny Caso-Lampaz who took chances joining the long queue of promising writers applying for Lee’s screenwriting workshop offered by ABS-CBN: “It was you who gave me a chance to explore my hidden talent in writing. I didn’t know what I was in there for. I remember I was applicant no.1054. So many questions to answer in the application form. I wanted to back out. After close to five hours in the line and the interviews, I got to see Sir Ricky Lee.”

After two weeks, Lampaz got a notice that she made it to that batch of aspiring screenwriters.

Added Lampaz: “That workshop with Ricky Lee started my love affair with writing. I knew nothing about writing before I met Ricky Lee. He didn’t just teach me. He was a guiding light. He taught me how I could put into writing the things hidden in my heart and soul. Thank you for being part of my dreams.”

In that PUP graduation speech, Lee opened up on some personal life trials.

Ricky Lee when he was given Doctor of Humanities honoris causa by Polytechnic University of the Philippines. (PUP Photo)

He recalled applying for a teaching position at the UP Filipino department. He was turned down three times. This even as the department used his short stories among required reading references.

But something good came out of that chapter in his life.

Without a college degree, Ateneo de Manila University accepted him in 1986. UP College of Mass Communications followed. Later, he got finally accepted at the UP Filipino department. On top of that, he got one of the university’s highest honors, the UP Gawad Plaridel.

I can imagine Lee’s screenwriting students writing their scripts for a documentary while he was awarded the title National Artist for Film.

Scene. Malacañang Palace.

President Duterte hands Lee’s medallion as National Artist.

Flashbacks as Lee puts on a smile for the commander in chief.

The day he was arrested (along with another future National Artist).

Day to day life during his detention days at Camp Bonifacio.

Scenes from his life as factory worker and pizza waiter.

His life as working student during his UP days: as salesman, accounting clerk, tutor, student assistant, proofreader.

Rewind to his graduation speech.

Final words to the graduates.

Keep working hard even with harsh trials.

Fight for your dreams. Your initial failure is not a measure of who you are and who you will be.

You don’t have to match other people’s success. Just be yourself.

Don’t be afraid to make a mistake.

Keep swimming in the sea of life. Don’t be daunted even if you drown.

Because when you fail, that’s when you find your real self.

Ricky Lee’s message after getting the National Artist award: “This honor is for writers who never get credits for their work; for writers who never get invited in film festivals; for writers who never got paid for their effort or are simply shortchanged; for writers who found other jobs because they could not survive on writing; for writers who pawned laptops; for writers who sold their souls just to get the proverbial break; for writers who still get proverbial rejection slips; for writers who tell the truth even if threatened with censorship and historical revision. This honor is for all of us writers who did well and who didn’t give up.”

Ricky Lee being congratulated by President Duterte in Malacañang Palace. (Presidential Press Photo)

Pablo A. Tariman contributes to the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Philippine Star, Vera Files and The Diarist.Ph. He is author of a first book of poetry, Love, Life and Loss – Poems During the Pandemic. He was one of 160 Asian poets who made it in the anthology, The Best Asian Poetry 2021-22 published in Singapore. Born in Baras, Catanduanes, he has three daughters and six grandchildren.

More articles from Pablo A. Tariman