Remembering the Forgotten 1953 Manila World’s Fair

/And that was the Philippines International Fair of 1953 (PIF), a wonderful but little-remembered major exposition that celebrated “500 Years of Philippine Progress.”

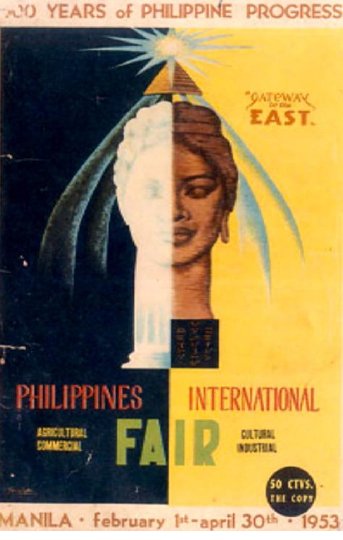

Logo of the 1953 Philippine International Fair. (Thanks to Isidra Reyes.)

Most world expositions are sanctioned by the Bureau international des expositions (BIE), the Paris-based organization which has the authority to allow the use the designation “Expo.” But you must be a dues-paying member of BIE to use that “privilege.” The 1953 Manila Fair (and the NY World’s Fairs of 1939 and 1964-65) were not BIE-sanctioned fairs but were still among the highest-attended such expos.

The PIF of 1953, Manila, on a clear bright day. This was the Lagoon of Nations with the thematic Salakot-Arch, symbol of the Fair towards the Agrifina Circle. Pavilions of Cambodia and Sweden at left. ((1326) Pinterest, c/o Otilio Arellano)

PIF 1953 was a big To-Do for its time, but strangely very little information on the Fair exists today outside the Philippines. Thanks, however, to the Internet, I found some scraps which helped rekindle my few memories of a special time in Manila’s post-WWII resurgence.

Early Plans – You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby!

The first stirrings for an international fair among Filipinos came about in 1941, when a major international fair was planned to commemorate vast tracts of empty land north of old Manila as the country’s future capital, after years of planning and legislating. The 1941 Fair was to have been on the scale of two international fairs of the U.S. in 1939 (the first NY’s World’s Fair and its West Coast twin that year, the San Francisco International Exposition of 1939 on Treasure Island in the SF Bay). It was also hoped that the fair in today’s Quezon Circle—ringed by government buildings—would be a permanent, annual event much like the annual Paris Expositions or the Leipzig Fair (of the industrial trade sort) in Germany.

The guiding force behind these fairs was an old and experienced hand—Arsenio K. Luz, the promoter and organizer for the historic Manila carnivals, 1921-1939. He was, one might say, the Filipino Robert Moses, the NY World’s Fairs’ promoter, of his time. Luz was a journalist, one-time Press Secretary and ghost writer of President Manuel Quezon, co-founder of the Rotary Club and, with other civic leaders, a founder the Boy Scouts of the Philippines movement.

Manila Carnivals impresario Arsenio K. Luz, circa 1930.

Here is a rare photograph of the main gate to the 1926 Fair—an example of one of the most elaborate and luxurious pieces of construction for something temporary.

That Fair in Quezon City was to open in mid-November 1941. However, by July-August, the winds of war were already blowing strongly in the Far East and elsewhere as well, and many nations started bailing out of that fair. With the Commonwealth’s attention diverted by the coming war, what was left of the 1941 extravaganza was a vastly scaled-down, mostly domestic county-type fair.

Barely three weeks after its opening, the hounds of hell were unleashed. Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Manila, Shanghai, etc., on December 7-8, 1941 and began the horrors of World War II. This abrupt turn of events all but erased any coverage of that short-lived fair in Quezon City.

A Young, Free Republic

WWII came to an end in August 1945. The Philippines gained its independence in July 1946. The United Nations took over from the League of Nations. Several other major nations—India, Pakistan, Israel, etc.—came into their own over the next few years.

After a nearly pulverized Manila was able to almost put herself together by 1950 and everything seemed alright with the world again, Arsenio Luz, with several civic-minded businessmen, picked up the pieces of their shattered 1941 dream. They set 1953 as the next opportune time to stage a new world’s fair. There was tacit support from the Quirino administration, but it could not fully fund the “showcase/PR” project as there were far more pressing needs to be addressed in nation-building.

The organizers’ major problem for a 1953 fair was that the “new” nation of the Philippines was only seven years old as an independent republic and this was really nothing to crow about. This short track record would be laughable compared with progress even in defeated nations, like Japan, Germany, and Italy that were well on their way to becoming first-world industrialized nations again.

The solution? Dredge up a collective 500 years of history and see how that stacked up. Thus, the chosen theme became “500 Years of Philippine Progress,” starting at 1453 when the archipelago was a motley collection of sultanates and tribes already trading in gold and conducting a healthy maritime commerce with neighboring kingdoms, to a straight shot into the American era of the 20th century of self-governance. Let anyone challenge “500 Years of Philippine Progress” as a shaky claim.

For a location, instead of revisiting the still bare Quezon City site, the organizers decided to stay at the Luneta, where the current Rizal Park plus the Sunken Gardens gave them 47 hectares to play with. More importantly, visitors would conveniently be lodged in the city’s few major hotels right there. There weren’t any major hotels in Quezon City then. Rizal Park would be renamed United Nations Plaza for the Fair. With the reality that the site was only on loan for three months, earlier dreams of establishing a major, annual international exposition were extinguished. However short-lived, the 1953 edition would at least be the first major, postwar international fair in the Far East (until Expo ‘70 in Osaka, Japan, 17 years later).

A Turbulent Background to the 1953 Fair

The 1953 PIF was held against a backdrop of turbulent events. Abroad, the Philippines had joined the United Nations-USA-led coalition in the Korean War by sending some 1,500 troops as befitted a faithful ally. At home, the Quirino administration had all but successfully completed the “airlift rescue of White Russians from Shanghai and Harbin” who fled the turmoil in mainland China. The resettled Russians were by then starting to find permanent homes in other countries. Then there was the Huk (Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon) rebellion still going strong that year. Finally, the second presidential election of the young Republic was looming.

The 1953 Fair was scheduled to run in Manila’s “spring” (February 1 – April 30, 1953) for very practical and economic reasons. It would not be necessary to air-condition the various pavilions in that period. Not being the typhoon season, expensive concrete foundations and steel frameworks would also not be needed. Lightweight construction would hold for 90 days.

Because the international part of the Fair would not be fenced-in, admission tickets could not be bought. A bond was floated to pay for the venture, and the organizers depended on large subsidies from private industry; namely, the country’s solvent enterprises at that time, which were mostly the Soriano companies, San Miguel Brewery and Philippine Airlines.

Plans for a layout in the grand style of the Chicago Fair of 1893 (the World’s Columbian Exposition) were laid out by noted architect Otilio Arellano. Twenty-five nations were initially invited to participate. Twenty became “seriously interested,” but only eleven accepted and actually built their pavilions.

The grand layout of the Fair showing the United Nations Plaza dominated by the many major pavilions and the Lagoon of Nations. The Jose Rizal Monument is at lower left corner; the Agrifina Circle in the back (upper right). The Sunken Gardens were on the upper left, behind Padre Burgos Avenue; and T.M. Kalaw is the avenue on the right. (from the PIF 1953 Official Souvenir program)

By design, there wasn’t going to be one specific Philippine “host-country” pavilion. Instead, the combined pavilions of 35 (out of the 52) Philippine provinces then, 18 chartered cities showing their wares, and various government departments and major corporations would cumulatively represent the best of a young but, per the fair’s theme, very much “progressed” Philippine nation.

Bullfights, Beauty Fights and an Ice Show Came to Town

To create extra excitement for the Fair, several unique events were offered as lead-ups to the Big Show.

First, was the return of bullfighting in Manila—not seen since the Spanish 1890s—but thanks to the Tabacalera Liquor Dept. (TLD) this time. TLD sponsored five sessions of bullfighting with noted Spanish toreadors and, of course, authentic Iberian toros (bulls) were likewise imported.

PhP: Philippine History in Pictures : 1890s: Bullfighting in Manila! philhistorypicts.blogspot.com)

The bullring where Spanish toro blood was spilled on Manila’s soil. Notice the Manila City Hall clock tower in the left back-ground. (Philippine History & Architecture Facebook Page)

The bullfights (corridas) were staged at an especially constructed wooden arena at Sunken Gardens across from Manila City Hall. The bulls arriving in 1953 made their one-way trip to Manila.

Three other wonders made their debut in the Philippines:

The Dancing Fountains (also called Waltzing Waters). Although fountains are as old as the Roman Empire, manipulated fountain shows set to music started with George I in England and Louis XIV in Versailles. Filipinos had never been treated before to regulated fountain shows with music. This also might have been Dancing Fountains’ first appearance in Asia. This show turned the Lagoon of Nations into a magical setting at night.

The Holiday on Ice Show, imported from Europe and Japan, was a paid admission spectacle. After the bullfights, the arena was converted to the Holiday on Ice venue, which opened in April in time for Easter and my 5th birthday.

Just as many people remember experiencing snow for the first time, I distinctly remember my seeing the ice stage for the first time. I had accompanied my father when we bought tickets one afternoon. My dad asked the Box Office if they would let us in just so a five-year-old boy would have a preview of an “ice show.” They very nicely obliged.

We approached the raised stage. Dad pulled away the tarp cover under a bright sun. (This was an exterior venue, unlike all the later ice shows which performed in roofed arenas.) Dad made me touch a corner of the huge sheet of ice. Wow. I had never seen a sheet of ice so big, but it still didn’t give me a clue to the wonders that unfolded at actual show time a few nights later. That was, to use a pun, a cool 5th birthday gift. Muchas gracias, Papá.

The First Roller-Coaster Ride in the Philippines. An even more thrill-seeking treat was added to the Amusement /Carnival Rides section of the Fair!

The first roller coaster ride in the Philippines (PIF souvenir program c/o Alex Castro)

Over-Abundance of Beauty Titles. And then, of course, what is an Asian/Filipino World’s Fair without a beauty pageant? Again, the hand of organizer Arsenio Luz could be seen in this aspect since beauty queens and her courts were a big part of the prewar Manila Carnivals.

For 1953, those matters came to a head when the first post-WWII Miss Universe, Armi Kuusela of Finland, arrived to grace the Fair with her presence. Kuusela had been invited by Filipino officials attending the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. When she came to Manila in March 1953 as the first Miss Universe gracing the first world’s fair in Asia, she met her future soulmate, local businessman Virgilio Hilario. Shortly thereafter, in Baguio, the stars aligned. The rest was history.

At stake at the Fair were not only the Misses Philippines, Luzon, Visayas, Mindanao, and Manila titles, but a Miss Pearl of the Orient crown as well. Cristina Galang of Pampanga eventually won the Miss Philippines crown, Norma Jimenez was Miss Manila, and Violeta Villamor was a double winner, winning the early “Pearl of the Orient” title and then grabbing the Miss Visayas crown as well.

An early loser who couldn’t even take the Miss Manila title (which was won by solicited tickets/votes) was a lass from Leyte, a naive Imelda Romualdez. The young Imelda, who was just making the rounds of Manila society, was reportedly so inconsolable after all the titles were handed out that then-Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson created a consuelo de bobo (consolation prize) title for her, only because she came from the prominent Romualdez clan. Out of thin air, Lacson conjured up the “Mutya ng Manila,” title just for Imelda. Imagine a one-horse race. How could one lose?

First Ms. Universe Armi Kuusela crowning the 1953 Miss Philippines Cristina Galang.

Galang being escorted by a young Ninoy Aquino.

Kuusela in her first taste of wearing the Filipina terno.

No-Show Beauty Queens

As you will see in the attached footage, Kuusela is shown in the company of Cristina Galang of Pampanga who won the top Miss Philippines title. It was thus assumed that Galang would represent the Philippines at the 2nd Miss Universe pageant in July that year. But when May rolled around, it suddenly turned out that Galang would not represent the country at Long Beach. Hence, a new pageant was hastily staged at the Manila Hotel to pick a replacement. The re-do winner was Cristina Monson Pacheco who wasn’t even in the original Fair line-up.

While Pacheco did get to strut her stuff in Long Beach in July, Kuusela, the outgoing Miss Universe, also became a no-show in Long Beach. Her visit to the Philippines resulted in a whirlwind romance-marriage to Hilario, which cut her Miss Universe reign short. After she and Hilario quickly married in Tokyo, Kuusela resigned her Miss Universe position and did not bother to return to Long Beach to crown her successor. The Miss Universe organization, only two years old at that time, to its credit, did not penalize the new Mrs. Hilario for her non-compliance.

Lone Surviving Moving Picture Record of the Fair?

Which brings us to what is probably the only surviving silent, moving color record of the Fair. Check out Philippines International fair 1953 - YouTube (purely visual; no audio nor cue cards).

The rare video became available thanks to the Varland family of Sweden. It came from the personal archive of Evin Varland, Sweden’s Consul General to Manila at the time. The video was 67-years-old when a relative, M. Varland, posted it on YouTube in 2020. The images are still remarkably sharp and the colors quite vivid considering this was shot on acetate, negative film nearly 70 years ago. Because it was diplomat Varland’s own personal recording, the semi-documentary understandably centers on his country’s participation at the Fair while still giving extensive coverage of the rest of it.

Then You May Take Me to the Fair

The Fair’s main “Gateway to the East.” Behind is the Roman Catholic Church Pavilion.

The Fair opened on schedule on February 1, 1953. Following is a sampling of foreign pavilions present: Belgium, Cambodia, Indonesia, Italy, Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, the USA and Vietnam. (These are screen-grabs from the Varland video.)

Sweden, in two stories no less. Materials used for the pavilion were shipped from Sweden. As the only Scandinavian bloc nation present, Sweden hoped to make a good impression with SE Asia and establish trade relations with the region.

Spain’s, designed by Manila architect Carlos Eduardo de Silva.

The USA Pavilion, designed by Carlos Corcuera Arguelles. This giant bell structure, lit up at night like a Vegas building, is one of the vivid images of the fair that remain in my mind.

Italy’s pavilion which looked like one big, windowless block.

Some of the pavilions from Philippine provinces, chartered cities and government Departments:

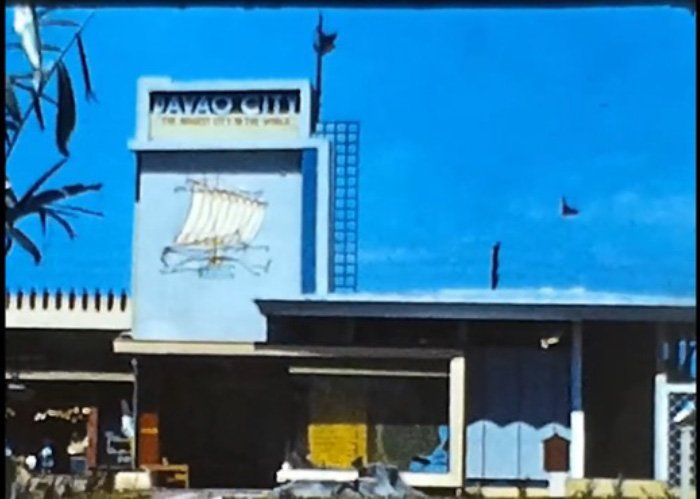

The City of Lipa pavilion beside Davao’s.

Ilocos Sur’s pavilion.

From the province and city of Cebu with a giant Lapu-Lapu over the slain body of Magellan.

Davao City

A highly advanced one from the National Power Corporation. Yes, that is rushing water, representing hydroelectric power from dams.

A 1:24 working scale model of the Mariveles Dry Dock shipyard complex.

A corporate pavilion from Yupangco & Sons, one of the leading piano emporia at the time.

Post-Fair Legacy

Since the Fairgrounds were not fenced off, no admission was charged, and no attendance records could be obtained (unless individual pavilions counted their visitors separately). When the Fair closed on April 30, 1953, no records of how many visitors actually came to the Fair existed, neither did such helpful stats as what percentage of fairgoers were local, foreign, legal ,or illegal residents, etc. Thus, it could not be ascertained whether the Fair ever met its projected mark of two million visitors.

Lost “Botong” Francisco Murals

The Fair saw the major debut of a rising graphic artist, Carlos “Botong” Francisco, who was a little-known, rising artist/designer who worked primarily on the graphics of local movies. He was commissioned supposedly by the National Library (whose contribution to the Fair would be Francisco’s work) to design two “tableaux,” something like the Bayeux Tapestry, which would manifest the “500 Years of Philippine Progress/History” theme. This was Botong’s first major commission, and the murals measuring 44 meters long each were going to adorn the two semicircular “commonly shared” Fair buildings just behind Rizal’s monument. So, drawing on Francisco’s expertise as a graphic artist for local films, the murals, executed on plywood and acrylic paint, were going to be set up like giant billboards (est. 5 meters tall) on the second story façade.

Has Anyone Seen the Other Half of the Original?

Below is a reprint of Francisco’s original study in watercolor of the first panel, which starts off with the “Malakas at Maganda Legend,” segueing to the arrival of Magellan and Christianity. This artwork measures 15” x 40” (38 cm x 102 cm). The other half of the artwork is thought to have survived, but Francisco supposedly gifted it to a relative who emigrated to the U.S. after the Fair. If any reader happens to know the whereabouts of the other original half, kindly contact the author via Positively Filipino. It would benefit Philippine patrimony and heritage to know of its existence.

This watercolor on paper of the first half of the total Francisco mural was sold at an auction in 2019 for Php 584,000 to a local collector.

Compare the screen-grabs below to the original study above. The Francisco murals section starts at the 6:26 mark on the video. [Here is the link to the video again to the Varland Video]

Left, the first Catholic mass in the Philippines is celebrated.

It was a major work of epic proportions by any measure. Local reaction to the monumental work was lukewarm for the most part, but since this was Francisco’s “international” debut of sorts, American magazines Time, Newsweek and other foreign press gave it major and mostly positive coverage. This launched the struggling Francisco as the country’s leading muralist for the next two decades.

Part of the second mural:

What happened to the actual murals? They were dismantled, but since Botong had not achieved major artist status then, no one except for the National Library seemed to care. The Library, which today sits in what was Fair grounds proper then, supposedly managed to recover a few panels, but the greater part is lost, ending up as housing material in shantytowns, i.e., “squatter housing.” I guess better as housing than as firewood. So, what the Library might have lies in storage. It’s truly tragic that the Fair administration, Arsenio Luz, and even Francisco did not undertake the necessary steps to save those historic murals for posterity.

One consolation from their loss is that Francisco repeated many of the same subjects in his later works, in one variation or another. In 1973, four years after his passing in 1969, Botong was posthumously awarded the second National Artist of the Philippines title (after Fernando Amorsolo). Botong supposedly died a penniless artist. But his most glorious, surviving panels are now safely on display at the National Museum of the Philippines, the Fine Arts Department, not far from the 1953 Fair grounds.

It is also safe to say that after the last pavilion and ride had been taken down, the Fair lost a lot of money, hence there was no second Philippine International Fair.

But the bullfights did come back to Manila two more times in the 1950s.

Holiday on Ice returned to the Rizal Memorial Coliseum in 1955; and then became a regular fixture at the Araneta Coliseum starting in 1960 (with it the Dancing Waters) and later, at the Mall of Asia Arena.

Organizer Arsenio Luz seems to have done nothing more of significance “expositions-wise.” He did win a Legion d’Honneur from France for his work for his last hurrah, the 1953 Fair. (FYI, Arsenio Luz is one of 14 Filipino recipients of France’s highest honor for foreigners to date.) He was also an uncle to visual artist Arturo Luz, who would win a National Artist of the Philippines title in 1997 himself.

In the election later in 1953, neither the Fair nor the humanitarian White Russian rescue chapter seemed to have helped President Quirino’s chances of reelection. He lost handily to the opposition candidate, Ramon Magsaysay.

The Huk situation never really went away.

The Americans and their bases left and came back; left and came back again,depending on who were in power in both Manila and Washington, DC.

Armi Kuusela settled in very nicely as a Filipina housewife to Hilario and Manila’s upper social circles. She would be the first in a long line of local and imported beauty queens who would make the Philippines home for many years.

It would be another decade or two before the Philippines would embark on other, grand international showcases, the first one of which was the Miss Universe pageant of 1974. This was followed by the International Monetary Fund confab of 1976, which saw a dozen four-star hotels spring up all over Manila. Then there was the First Manila International Film Festival of 1981 in the “haunted” Manila Film Centre. Those were all projects of the one-time Miss Manila 1953 loser, neé Imelda Romualdez, who became the country’s high-flying first lady in the ensuing decades.

While there is substantial philatelic documentation of the 1953 Fair, few significant artifacts—not even a time capsule—exist for such a major event after the gates closed. It is truly puzzling that not more documentation exists for what was, by all accounts, an ambitious achievement for a new country just recovering from a devastating war. Even the very anal Wikipedia, for some ridiculous OCD reason, refuses to recognize this exposition, as if graphic evidence from the rare (Swedish) video, would lie.

There are also rather large holes in the collective memory of Manilans about the event. I have met very few people who have some memories of that singular event. Even an adult son of one of the Fair’s board of directors cannot remember a single moment of the Fair 70 years later. He was 20 then, but his recall button draws a total blank.

Finally, thanks again to M. Varland for sharing his family’s priceless memento. What sweet memories of a long-ago, special Manila spring it stirred in me.

SOURCES:

Video Philippines International fair 1953 - YouTube, c/o M. Varland, posted July 30, 2020)

Alex Castro, blog - MANILA CARNIVALS 1908-1939 (for sharing the Official PIF 1953 Souvenir Program).

“Remember When?” by Danny Dolor, Looking back at the 1953 International Fair | Philstar.com

PHILIPPINES PREPARE ASIA'S FIRST WORLD'S FAIR - The New York Times (nytimes.com). December 14, 1952

IMELDA MARCOS, Carmen Navarro Pedrosa, St. Martin’s Press. © 1987

Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes, Myles Garcia, MAG Publishing, © 2016

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. He has written three books:

· Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2021);

· Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes (© 2016); and

· Of Adobo, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles (© 2018)—all available in paperback from amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, UK and Europe).

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians, contributing to the ISOH Journal, and pursuing dramatic writing lately. For any enquiries: razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia