Re-enacting the Bataan Death March: A Personal Journey

/More than 7,000 marchers get set to start this year’s Bataan Memorial Death March. (Photo by Jon Melegrito)

Now I can say I’ve experienced an incredibly tiny portion of what my father, a Bataan Death March survivor, and his comrades went through 75 years ago. I feel personally connected somehow to their physical and spiritual hardships that for many were just too great to bear.

So, for the first time, I’m participating in the Bataan Memorial Death March, a reenactment of the 65-mile tortuous trek by 75,000 Filipino and American soldiers following their surrender to Japanese Imperial Forces in April 1941. Forced to march for days with minimal food and water, about 9,000 Filipinos and 1,000 Americans perished. Thus the infamous name, “Bataan Death March.” Many more died in prison camps.

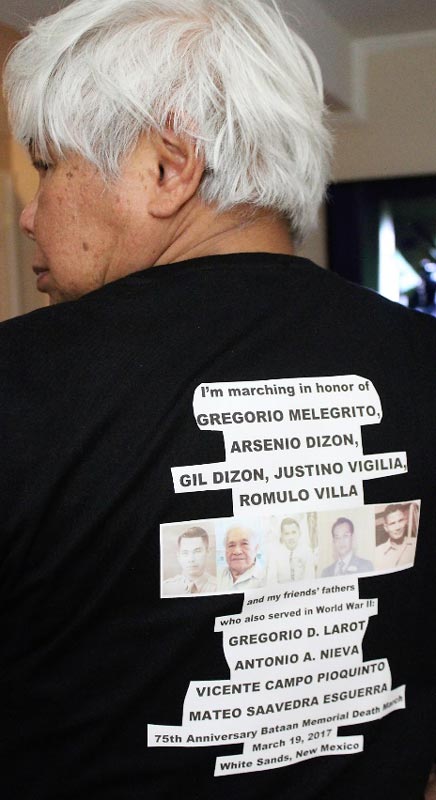

The author’s shirt carries the names of his father and uncles. (Photo by Jon Melegrito)

On its 28th year, the March 19 event honors the heroic service and sacrifice of those brave soldiers who fought under the American flag in Bataan and Corregidor. Adding significance to this year’s marathon is the 75th anniversary of the fall of Bataan, commemorated over the years as “Araw ng Kagitingan,” or “Day of Valor.” The participation of 7,200 marchers is the largest ever. It’s also the first time Filipino American participation gained prominence in the history of the march, with the Philippine Flag and the singing of the Philippine National Anthem featured in the opening ceremonies.

White Sands Missile Range, where the annual marathon is held, is an expansive U.S. military installation located in the rolling white dunes of New Mexico. We learn later that this was the testing site of the world’s first atomic bomb explosion. That same bomb exploded in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, ending the war in the Pacific and consequently Japan’s atrocities in the Philippines.

With so much of our own history connected to this Missile Range, it seems only fitting that the Bataan Death March is memorialized in this vast expanse of desert, a venue for various tests related to war and destruction and also liberation.

Filipino World War II Veteran Rey Cabacar of Fort Washington, Maryland is among the many Filipino Americans from across the country participating in the march. (Photo by Jon Melegrito)

Bataan Death March survivors, their families and descendants stand at attention during the roll call and playing of Taps. (Photo by Jon Melegrito)

It’s still dark when we gather at the staging area for the opening ceremonies. Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba, son of a Bataan Death March survivor, recounts the “brutal, brutal, brutal” ordeal of his dad and his comrades. “Let’s be inspired by their heroism,” he implores. “Let’s do this for them, for their families, for us and for our country.”

I’m marching for my dad, Gregorio Melegrito. I have his picture and name, along with three other uncles, ironed on my shirt. I’m proud marching for them as a descendant of Bataan Death March survivors. Two uncles escaped from a POW camp and led guerrilla units in Nueva Ecija. They never wanted to surrender, my dad used to tell me.

They all have passed away, however, and never had a chance to come to this desert. The only Filipino Bataan Death March Survivor who ever did was Maj. Jesse Balthazar of Falls Church, Virginia Despite his ailing health, the 95-year-old Purple Heart Awardee came with his family last year to witness the memorial ceremonies. He died a few months later.

By dawn’s early light, the marchers sprint from the starting line. Many of them have done this before, completing 26.2 miles across trails of hot sand and hilly terrain.

The grueling 26.2-mile trek across hot sands and hilly terrain is an annual event to honor the 75,000 Filipino and American soldiers who fought in Bataan and Corregidor. (Photo by Jon Melegrito)

The author (left) and family members of Team Garibato of Seattle, Washington pose for a photo at Mile 7. (Photo by Jon Melegrito)

Along the way, I encounter sons and daughters and grandchildren of Filipino World War II veterans. One of them says it’s a “pilgrimage.” Another describes it as a “connection with the past.”

For me, it’s a personal journey to honor my father and the suffering he endured. Because of his will to survive, I am here today blessed with life and the love of family and friends. It’s humbling, just knowing how these soldiers persevered, how they were inhumanely subjected to a most frightening ordeal, and how in the end they not only endured, but prevailed.

I reach the finish line and I try to imagine how the Bataan Death March survivors must have felt when they finally reached their destination after days of walking in the sun. Tired and exhausted, they were hopefully relieved the march had ended. But while I only suffer minor body aches and am able to fly back to my family in Maryland, they endured long months as prisoners in a concentration camp, never knowing if they’ll ever return home.

Marching in the desert with other descendants of Bataan Death March survivors allows us not only to remember them, but also to keep their history alive by letting others know what they fought and died for, and why we stand on their shoulders, humbled yet proud of their lasting legacy.

Jon Melegrito is the Executive Secretary of the Filipino Veterans Recognition & Education Project. He lives with his wife, Elvie, in Kensington, Maryland.

More articles from Jon Melegrito