Raping Sugarland

/The twist in my family’s personal history — our descent into indignity — came about because of the late dictator’s rape of Sugarlandia in the 1970s.

This was in the mid-1970s, right around the time I was born – and because I was a newborn when the New Society was being touted as the “saving grace” to a troubled country, and because I only stumbled on this information in my adult years, I was never able to ask the proper probing questions, until now.

No one in my family ever talked about it either, except in broad strokes that told a simple story of lost fortune: that once we had an extensive sugar plantation in the rich farmlands of Bayawan (Negros Oriental) with the opulent lifestyle (and a vast circle of friends) that went with it, and then we lost it all. No one mentioned Marcos, and I attributed the story to quirks of fate. Bad things happen to good people.

We did not talk about the origins of our reduced circumstances, perhaps out of shame. I, on the other hand, would have been the one person in the family to ask the terrible questions for the sake of writing — but I simply did not know.

What could not be denied, however, was the state my family was in those later years in the 1970s, and especially more so throughout the trying decade of the 1980s. I did not feel much hardship because I was too young to notice anything beyond the regular hunger pangs I felt — but I know now that my older brothers, all five of them, must have. They bore the brunt of my family’s sudden poverty because they were aware firsthand of what they’d lost. When I’d go through old photos in family albums, I’d see them enjoying lavish birthday parties. My brothers in those photos had birthday cakes and birthday candles, always surrounded by an assortment of people I didn’t recognize hogging tables laden with abundant feasts. I never had a birthday party — but I honestly didn’t know what I was missing until my 30th birthday when friends surprised me with a birthday cake, and only then did I realize I had never blown a birthday candle in my entire life.

My brother Dennis enjoying his second birthday in 1969. (Photo courtesy of author)

We were very poor; we could barely eat three square meals a day. Things became so hard that when the family was finally forced to sell off our Bayawan house and our car (a yellow Sakbayan) to avoid the stigma of foreclosure, the only recourse was for the family to move to Dumaguete City in 1980. This was when the financial crunch was finally tightening around the illusion of Marcos’ New Society.

We lived like nomads in that decade, moving from one house to the next in search of cheap rent. This is what I remember most from my childhood — all the houses we stayed in, from a small compound at the Capitol Area to a wooden house with many rooms in Calle Sta. Rosa, from an upstairs apartment overlooking Holy Cross High School to a secluded one in an alley off Silliman Avenue, from various apartments in Bantayan to a virtual zaguan of a rickety old house in the bowels of Tubod.

My mother, who was once a society belle in her hometown of Bayawan in the flush years of the 1950s and 1960s, was reduced to a skeleton of a woman darkened by the sun as she went from house to house selling peanut butter she herself made — just to be able to feed us. She had kept in touch with many of her old friends, some of them still well-off, and most helped her out by buying her peanut butter. And when one of them would throw birthday parties, she’d take me along — her youngest child — just so I could have a proper meal.

My mother still loves to tell this particular story from that time: that once, when I was 11 or 12, I was so hungry after not being able to eat the whole day that I woke her up in the middle of the night, urging her to pray with me, so that God would listen and give us food. A miracle came: the next day, an anonymous friend sent us a whole bag of groceries. Until now, that sautéed sardines my mother prepared remains the best meal in memory.

In the 1980s, my mother would take me around with her to attend friends’ birthday parties just so I could eat properly. (Photo courtesy of author)

Our reprieve came with the usual story of many Filipino families. One of my brothers managed to work abroad just as the 1990s came along — and only then, with the remittances he sent the family, could we breathe properly again. I remember buying our first refrigerator. I remember buying our first TV. I remember buying our first Christmas tree. I remember our first car. I remember moving into our new house we didn’t have to rent anymore.

Where does Marcos come into the story?

“The personal is political,” so the old mantra goes. This truism is an honest accounting: our personal circumstances and experiences are rooted in, or invariably dictated by, the politics that surround us, especially in issues of inequality.

This was my prompt, and when I used this as the framework with which to see my family’s history, I stumbled into a rabbit’s hole. When I went deeper, I was confronted by facts that had not been readily told to me, not even by my family. The twist in my family’s personal history — our descent into indignity — came about because of the late dictator’s rape of Sugarlandia in the 1970s.

Here’s a bit of history.

Negros enjoyed decades of untold wealth because of one crop that grew abundantly on the island: sugarcane. All over the provinces of Negros Occidental and Negros Oriental, landed families controlled haciendas that produced sugar for export, particularly to the United States. You can still see remnants of this gilded age: the beautiful houses of Silay City and Bais City, even the famous “sugar houses” of Dumaguete, the small seaside mansions of Negrense landowners that line Rizal Boulevard.

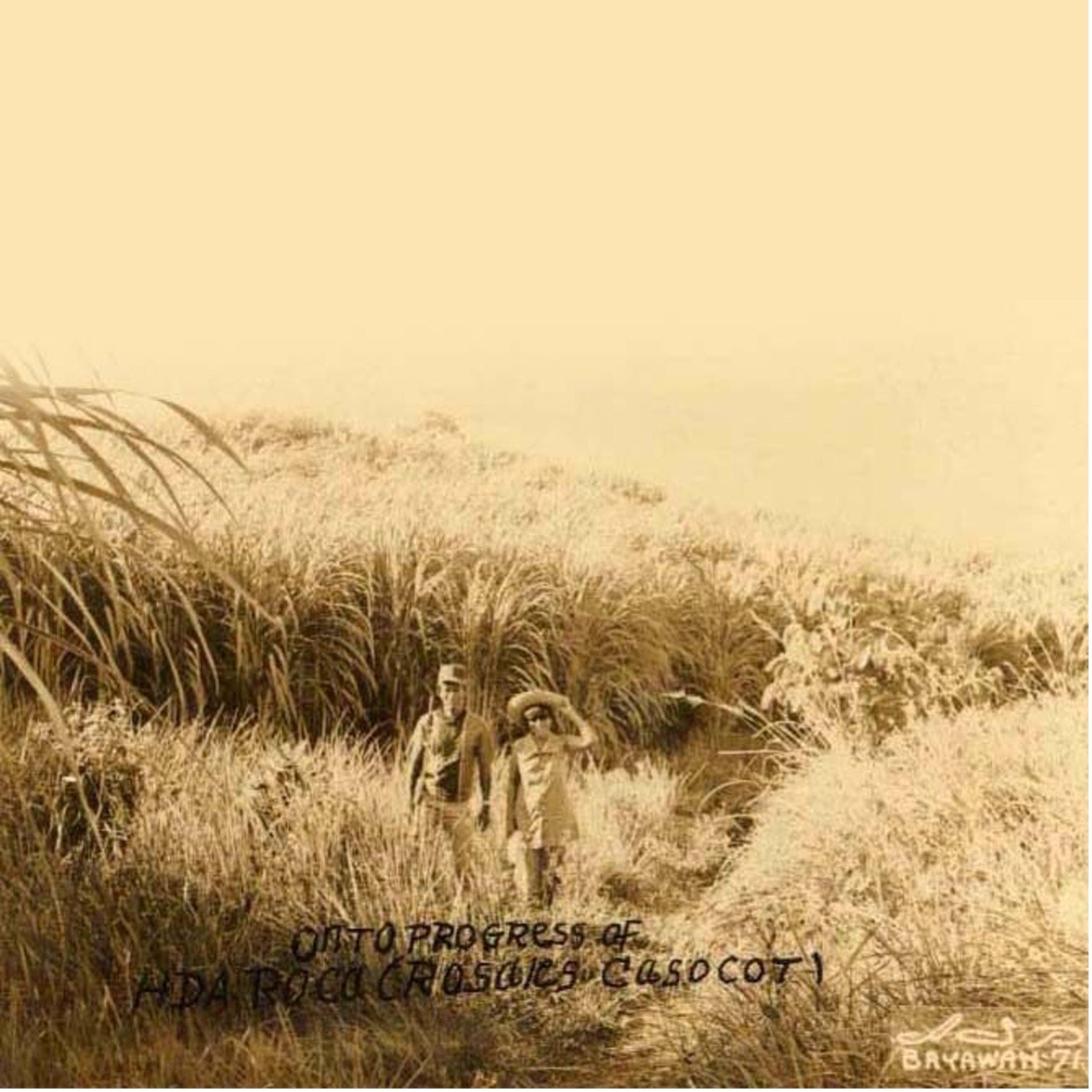

Families of more modest means — including mine — were also able to tap into this market with sizable landholdings devoted to the crop. Our plantation in Bayawan was named Hacienda Roca — after “Rosales Casocot” — and for many years, it sustained my family and catapulted us to the higher echelons of Bayawan society.

My father and mother in Hacienda Roca, Bayawan in 1971. (Photo courtesy of author)

And then the United States ended its sugar quota in 1974, after which Ferdinand Marcos — only two years after declaring Martial Law in the country (and thus having the power of life and death over everyone, even rich hacienderos) — appointed cronies “to head a state-owned marketing and trading monopoly” of the sugar industry, writes Inday Espina-Varona for Licas News.

On paper, Marcos and his economic advisers argued that it was a necessary move, because “pervasive market failures were the root cause of the decline of the sugar industry” — this, according to a 2001 paper by Gerald Meier — and that to rescue the industry, “central coordination was crucial.” Marcos called for the government to replace the market “in order to stimulate the market development of the sugar industry.” He established the Philippine Sugar Commission or PHILSUCOM in 1976, as well as its trading subsidiary, the National Sugar Trading Corporation or NASUTRA, to do the job.

NASUTRA was given the sole power to buy and sell sugar, set prices paid to planters and millers, and purchase companies connected to the sugar industry. In May 1978, the Republic Planters Bank was established “to provide adequate and timely financing to the sugar industry.”

Except that this was all illusion, good only on paper: Marcos and his cronies never paid back the planters — including my family — for the sugar NASUTRA got from them. All the money went to the pockets of Marcos and his cronies.

Inday Espina-Varona further writes: “[Marcos and his cronies] robbed sugar planters, taking advantage of fluctuating global prices and drowning landowners in debt. That, coupled with centuries of irresponsible lifestyles and a feudal system that reserved land only for the rich, led to the collapse of the island’s economy.”

And then that financial disaster blew up into an even bigger one:

“On Negros’ vast plains, man — not nature — ushered in famine,” Inday Espina-Varona writes. “Almost 200,000 workers lost their jobs. Hacienda owners, facing bankruptcy, fled to the safety of cities, abandoning families that had served them for generations. Unemployed workers on paper enjoyed some social amelioration. Those who actually received this were the exception. Corrupt officials had siphoned off funds to personal coffers or to bankroll the extravagant habits of the dictator’s family. Farm labor flooded the cities to scrabble for work but there was little to be had.

“In trickles, and then streams of misery, children began arriving in hospitals with swollen bellies, stick limbs, and eyes that drooped or stared sightless from pain. Some were too weak to talk; many could not walk.”

Negros suddenly became known worldwide for its starving children. Some of you might still recall the 1980s campaign that screamed: “Feed the Hungry Children of Negros.” In the public grade school I attended in Dumaguete in the early 1980s — during the last years of the Marcos regime — I remember well what that entailed: being fed pospas (rice gruel) every day during recess. I hated pospas.

The most infamous of these “hungry children of Negros” was a boy named Joel Abong whose skin-and-bone visage appeared “on the front pages of newspapers and the covers of magazines,” writes Inday Espina-Varona, who covered the ill-fated child’s last days.

A photo taken on May 4, 1985 of young malnutrition victim Joel Abong, which has become iconic of the situation in Negros in the 1980s. (Photo by Kim Komenich)

She notes: “Joel had pneumonia and tuberculosis. He was brought in with bones so brittle doctors had to wrap padding around his limbs. Joel’s body was the size of a baby. Stringy hair the yellow-brown of severe malnutrition lay limp on a head that seemed grotesquely big. A rattling sound accompanied every breath. His father was one of those who had fled the cane fields. On an island where people joked about shoveling money from the ground, Joel’s family had literally starved. My mother headed that hospital’s pediatric department. She came home every night in a silent rage. Some nights she could hardly eat; food was a reminder of her patients. Doctors couldn’t save Joel. He was not alone.”

By 1985, 10% of Negros’ children were suffering third-degree malnutrition, according to Dr. Violeta Gonzaga of La Salle College in Bacolod.

She notes: “Joel had pneumonia and tuberculosis. He was brought in with bones so brittle doctors had to wrap padding around his limbs. Joel’s body was the size of a baby. Stringy hair the yellow-brown of severe malnutrition lay limp on a head that seemed grotesquely big. A rattling sound accompanied every breath. His father was one of those who had fled the cane fields. On an island where people joked about shoveling money from the ground, Joel’s family had literally starved. My mother headed that hospital’s pediatric department. She came home every night in a silent rage. Some nights she could hardly eat; food was a reminder of her patients. Doctors couldn’t save Joel. He was not alone.”

By 1985, 10% of Negros’ children were suffering third-degree malnutrition, according to Dr. Violeta Gonzaga of La Salle College in Bacolod.

“Even with the Chico Dam controversy and the murder of Macli-ing Dulag?” I asked.

(Historical aside: In 1973, a year after Martial Law was declared, the Marcos regime proposed the Chico River Dam Project, a hydroelectric power generation project involving the Chico river system that encompassed the regions of Cordillera and Cagayan Valley — without consulting the tribes in the area. Locals, notably the Kalinga people, resisted fiercely because of the project’s threat to their residences, livelihood, and culture — and the project was soon after shelved in the 1980s after public outrage in the wake of the murder of opposition leader Macli-ing Dulag. It is now considered a landmark case study concerning ancestral domain issues in the Philippines.)

“Clueless,” Frank said. “Even Sagada is hati (split).”

I thought back to what Marcos did to Negros in the 1970s — and I blinked from the sheer exhaustion I felt after realizing that even people from a land that has been raped (or threatened with it, as was the case of the Cordilleras) could still be so enamored by the son of that rapist, someone who insists to this day that no rape ever happened.

I doubt my mother — who is now 89 years old — still chases fanciful dreams of a return to the old splendor she enjoyed in Bayawan in the gilded age. I know she has come to a place of peace, having come to a reckoning with that past and the immediate catastrophe that followed it that saw her destitute and that saw her struggle so hard to feed her family (although she still managed to put through six sons studying at the very expensive Silliman University). The hardship ultimately strengthened her, and for that she is grateful.

But to forgive Marcos and what he had wrought?

Never.

Ian Rosales Casocot teaches literature, creative writing, and film at Silliman University in Dumaguete City, where he was Founding Coordinator of the Edilberto and Edith Tiempo Creative Writing Center. He is the author of several books, including the fiction collections Don’t Tell Anyone, Bamboo Girls, Heartbreak & Magic, and Beautiful Accidents.

Reposted with the author’s permission. This version was posted in Rappler on May 8, 2022.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Positively Filipino.