POW No. 24

/Lt. Col. Federico Peralta survived the Death March and was incarcerated at Camp O’Donnell in Capas, Tarlac.

First published in Inquirer.net. Reposted with permission from the Peralta family.

I arrived in Bataan on New Year’s Day of 1942 with the contingent of the division surgeon, Col. Jose Gonzales Roxas. Our division was given the mission of defending the southeastern coast of Bataan.

The sector was comparatively quiet except for the presence of Japanese snipers that infiltrated our sector. But by March, we began to feel the lack of food. It became so critical that we subsisted on soft-boiled rice twice a day with canned sardines or salmon as viand alternately.

To augment our dwindling supplies, we slaughtered carabaos and pigs that belonged to civilians who lived nearby. Monkeys were eaten and even stray dogs were not spared.

At the time, the USAFFE defenders, whose numbers had been decimated by disease, injury and death, fervently hoped for provisions from America to arrive.

One bright hope of the beleaguered Filipino-American troops was the expected arrival of a “one mile convoy” in a matter of days that would bring personnel, supplies and materials.

The convoy never arrived.

Instead, the Japanese reinforcement came and launched a major offensive in the early part of April. They bombed the hospitals and ammunition dumps.

Taking advantage of their superiority and firepower, the Japanese broke through our lines, and all of our efforts to stop the enemy’s advance were futile. With no naval support, badly outnumbered and inadequately equipped, the USAFFE defenders faced a hopeless situation.

Realizing our desperate condition, the American commander, Maj. Gen. Edward King, ordered the soldiers to stop all resistance. After the surrender, the Japanese ordered the troops to march from Bataan to San Fernando, Pampanga.

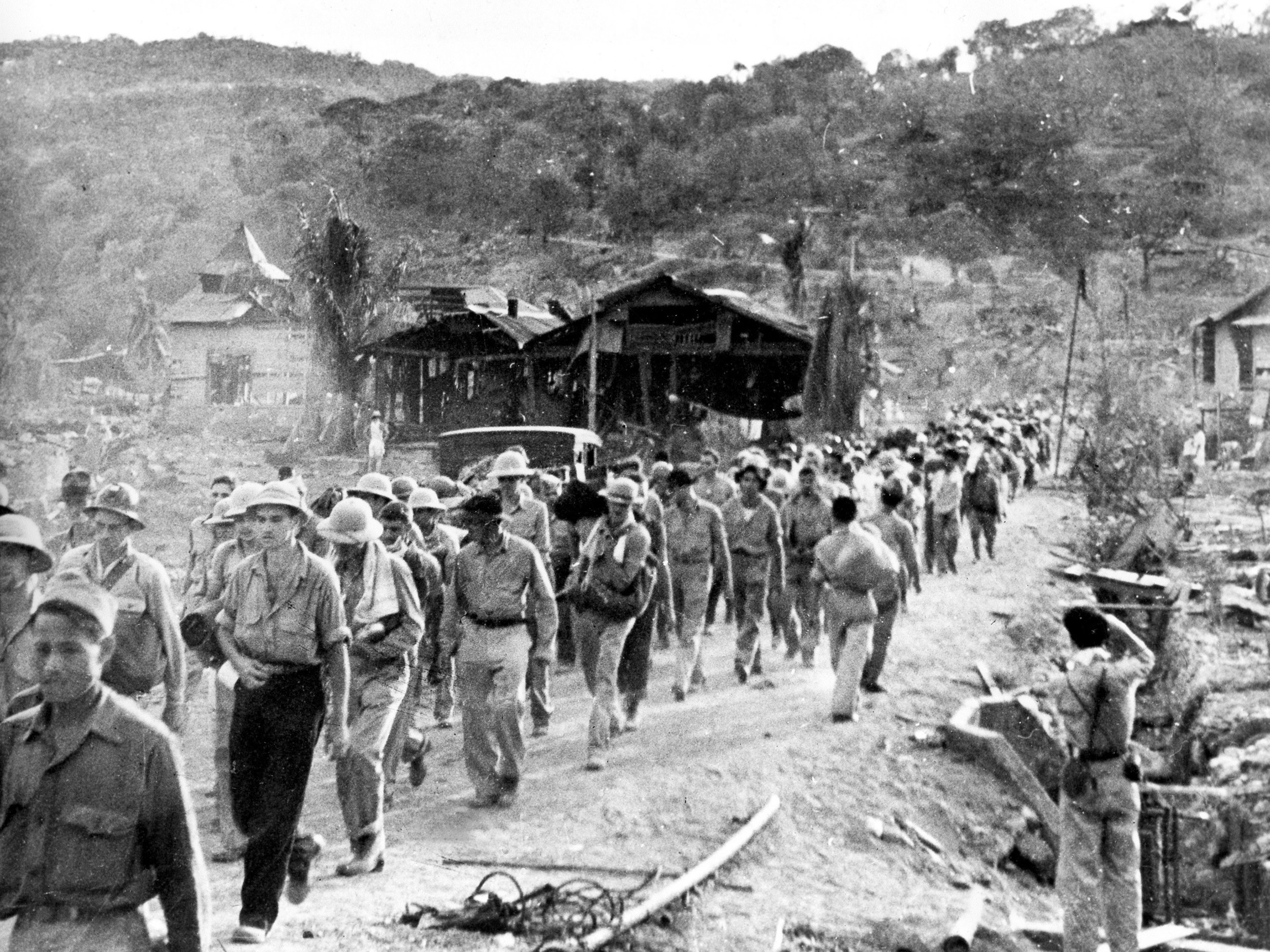

Death March

American and Filipino prisoners-of-war on the Bataan Death March (Source: United States Air Force)

Thus, began the infamous Death March, one of the most tragic episodes of the war that lasted for four days and four nights, covering a distance of 106 kilometers, of which I was one of the survivors.

During the first day, thousands of us who formed a kilometric line of marchers, four abreast, trekked with enthusiasm that at the end of the journey transportation would be available to bring us to our homes.

It turned out otherwise, and we were incarcerated instead. A notice was passed around “that the Japanese could guarantee our lives if we do not escape, and those who will, will be shot.”

I was one of those who did not take any chances to escape, inspired by the thought that I might still see my family someday. There were those who took the risk and escaped, some were lucky, some were shot dead.

A pre-world War II photo of the Peralta family. The author is standing second from left.

Despite the difficulties, the marchers continued night and day, rain or shine, with brief halts during the night. Some of those who were dog-tired collapsed, the rest carried on—wet, cold, hungry and afraid.

The Japanese guards were harsh and cruel. Anybody who broke the line because of a malaria attack and dysentery were subjected to ridicule and gunned down. Hundreds of marchers who could no longer walk were brutally beaten up and kicked by heartless guards.

After a brief halt caused by the misalignment of the marchers, I was separated from my friends. Early the following morning, I experienced my first malaria attack and was chilled to the bones. I rolled myself down toward the soft shoulder of the road and landed on a sugarcane field.

Strange episode

After the attack, although weak and exhausted, I managed to twist off a stalk of sugarcane. But I was seen by a group of Japanese on patrol. They shouted, “Kurah! Kurah!” and gestured to me to approach.

“This is my end,” I told myself, but prayed so hard for help and deliverance. Without much choice, I approached the Japanese and resigned to my fate.

But my faith in God was greater. For every second that I stood before the Japanese, I expected to be slapped, kicked and even shot.

To my astonishment, they laughed out loud. Probably, it was because of my appearance and to gloat at our defeat and subjugation.

They told me to follow them and we walked until we reached their tent under a huge mango tree.

“You doctor?” one of them asked me.

“No,” I said.

They thought I was a doctor because of the Red Cross brassard on my left arm and from the first aid kit that I had.

“I’m a medical aide,” I told them.

They took my first aid kit and rummaged through its contents. They took turns in figuring out what the items in the kit were for.

Food

At that moment, the bowl of rice and the aroma of smoked fish on the table caught my attention. My mouth watered, as I was without enough food the past days.

Surprisingly, the Japanese invited me to eat. Without waiting for a second invitation, I ate to my heart’s content. I ate like a glutton.

While I was eating, one of the Japanese took the thermometer he found in my first aid kit and began to use it.

The others found the adhesive tape and bandages handy. Some took the Atabrine and Quinine tablets.

While they were busy deciding who should take the rest of the contents, I continued to eat as fast as I could.

In no time, I consumed everything on the table. I regained my composure and was fully satisfied.

Then I found out that nothing was left inside my first aid kit except the emergency medical tags and the 5-cc hypodermic syringe.

The Japanese gave me a bag of rice and a bottle of fresh water—perhaps, the price for my first aid kit. Truly, God heard my prayers and protected me.

They ordered me to go and I did, hurriedly. It was almost noon when I rejoined the march.

Not all Japanese were bad

I walked animated with the thought that after all, not all Japanese were cruel and inhuman, some were kind and considerate.

I walked with renewed vigor until I saw a man slumped on the ground by the pond, bleeding and reaching for a fruit on an overhanging bough. When he got it, he was shot.

Some of us were hit with rifle butts when we attempted to drink from the artesian wells along the road.

The night overtook me in Limay, a town in Bataan overlooking the sea, where we were allowed to rest for the night.

Most of my comrades took time out to cook whatever they could. I looked around and saw the city of Manila across the bay. I knew that the journey’s end was near.

I also saw Corregidor to my right, the pitiful target of continuous artillery barrage.

I managed to improvise a bed out of cogon grass. I lay down and stretched myself flat.

The breeze was cold. I reviewed the past and evaluated the future then fell asleep.

Not long afterward, I woke up with a lassitude and severe headache and fever. I knew I would chill again and I did. The attack was so terrible that my teeth rattled.

“Continue the march!” the Japanese guards shouted.

Moving wearily and laboriously like living skeletons, we marched on. Aligning and realigning four abreast was total harassment. In all that commotion, I lost my bag of rice and broke my bottle of water.

After we had walked for almost two hours, I heard the guards yelling, this time to align ourselves in single file, as they dashed toward the rear of the column. I knew they had something in mind again.

We stood still. Then I noticed a checkpoint ahead where everyone was being physically searched.

Search and seizure

Disregarding all rules of civilized warfare, everything valuable to the prisoners were confiscated—money, watches, jewelry, fountain pens and anything that suited the guards’ fancy.

As I approached the checkpoint, I made up my mind to give up my Elgin watch and hoped they would spare the money I had on me.

A Japanese officer was supervising the search and inspection while noncoms did the confiscation. Money and watches were preferred.

Nothing escaped detection by the greedy guards. Money folded and hidden in pants’ seams were found and taken. But some prisoners who looked destitute and weak were allowed to go unmolested.

As the search was rigid, three hours had passed before my turn came. The guards had watches strapped on from wrist to elbow and they readily noticed my watch, which I gave right away to divert their attention so that they would not search me further.

But one guard saw my gold necklace with a crucifix, which I handed over with a prayer.

My original plan of diverting their attention worked and I was not searched further. Had that happened, the money taped to the sole of my foot could have been found.

Concentration camp

It was very late in the afternoon when we reached Lubao town in Pampanga. It rained so hard and since it was already dark it was easy for us to slip away unnoticed. The situation was so inviting that many took advantage of it, especially those living in the vicinity and neighboring provinces.

We reached San Fernando the following day, the final day of the march. We were crammed into five warehouses that although large could hardly accommodate all of us.

My malaria attack was over when we were marched again, this time to the railroad station. We were put on railway boxcars and taken to Capas, Tarlac province.

From there, we walked 8 kilometers to Camp O’Donnell. On our way, we were greeted by sympathetic people who lined the roadsides. They gave us fruits, rice cakes and drinks. They wept and prayed because of the uncertainty that we faced.

Our group reached Camp O’Donnell in the afternoon of April 15, 1942. The camp, which used to be a training place for soldiers, had been converted into a concentration camp for war prisoners.

We were soon divided into groups and subgroups. The Filipino group was under one Filipino general.

Ailing prisoners

The majority of us were sick of malaria and dysentery and were malnourished so the camp eventually became a veritable hospital ward.

It was made of light materials and could accommodate 100 to 150 patients on its two decks. Some of the barracks were so old and dilapidated that one of the upper decks collapsed, resulting in serious injuries to a number of patients in the lower deck.

I was designated assistant ward master at wards with more or less 80 patients. In the afternoon, I segregated the seriously ill patients who urinated and defecated unknowingly.

Some of the patients who were totally taken by illness just died, mouths open and devoured by flies. I usually had 15 or 25 dead patients in the morning, and likewise at the other wards.

Prisoner count

A physical inventory by the guard was scheduled in the morning. Any shortage of or an excess in the number of patients without reasonable explanations could result in grave reprimand or punishment. A hard punch or whipping with a rifle butt in the face was often the punishment.

We assistant ward masters remedied the excess or shortage of patients by loaning some from other wards and vice versa. The discrepancies happened simply because patients got lost on their way and ended up in the wrong wards in returning from the latrines.

Daily calisthenics (rajo taiso to the Japanese) was conducted, and we were made to recite aloud “The Doctrine of the South-East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” in Nippongo.

The food served was balled rice rolled in salt. More often than not, the rice was unevenly cooked, not to mention prepared by dirty hands. At other times we had boiled sweet potatoes.

Cows commandeered by the Japanese were slaughtered and the meat was distributed to the kitchens. Once the beef was cooked, it barely reached the seriously ill patients in the wards. Of course, the lion’s share went to the kitchen personnel.

There was always a struggle for food and only the fittest got to eat. Commotion and pandemonium happened during meals, a to-each-his-own kind of thing.

Profiteers

Canned goods found their way to the camp through the grass detail—people sent out to get grass for the guards’ horses. The buy-and-sell business was done in Capas.

The goods brought to the camp were sold at exorbitant prices. I remember buying a can of sardines for P50 and a can of corned beef for P80.

Prisoners who were never assigned to the grass detail became victims of fellow prisoners who turned profiteers. In the same manner, the lack of medicine made some prisoners rich overnight. Quinine tablets were sold at P5 each and sulfa drugs went for P10 a tablet.

Those of us who did not buy medicines because we found the cost steep or we had no money, boiled guava tree bark, which had medicinal properties good for diarrhea and dysentery.

Security inside the camp was quite strict and rigid. The camp was enclosed with double live-wire fences. I saw a prisoner shot dead while attempting to escape—meant to discourage the rest of us from doing the same.

No sanitation

With utter disregard for the elemental rules of hygiene and sanitation, the Japanese never provided us with proper facilities for waste disposal. Latrines were far from the wards and were just straddle trenches. In no time, they were full and looked like boiling pits with maggots feasting on the filth.

At night, prisoners afflicted with diarrhea were forced to stop anywhere, and evidence of their nocturnal suffering was visible in the morning.

Water was so scarce, no one took a bath during our entire four-month confinement in the concentration camp. As a result, most of us were afflicted with body lice, which bit and made us quite uncomfortable at night.

In the morning when the sun was up, all of us, regardless of rank and position, were busy killing lice, which hid in the seams of our pants.

Deaths rise

American and Filipino prisoners-of-war on burial detail at Camp O’Donnell after the Bataan Death March (Source: U.S. National Archive)

Deaths increased daily from 100 a day during the first month to nearly 300 or more in the early part of August. The bodies were just wrapped in army blankets slung on bamboo poles and taken to the burial place.

Burial details were twice a day, morning and afternoon. The graves were dug to accommodate five or more bodies but as deaths increased tremendously, bigger and wider graves were dug to fit 20 or more bodies.

Since more graves were to be dug, oftentimes burial was hurriedly done, thus some hands and feet were uncovered.

I could have been one of those who perished had I not been released. My prayers to see my family were answered. God was with me all the time.

On Aug. 4, 1942, I was released on parole with the second batch as Prisoner of War No. 24.

(Inquirer Editor’s Note: Lt. Col. Federico A. Peralta kept his release paper written mostly in Japanese. Upon release, he was among those made to board the train to Manila. His older sister, a Benedictine religious, had him met at the train station. He stayed for a while at St. Scholastica’s College and wore clothes borrowed from a priest.

Peralta wrote this piece in 1992, the 50th anniversary of the Death March. He died in the United States in 1995 at the age of 80. Peralta and his wife, Maria Luisa, raised nine children. He left this manuscript with his daughter Celeste. He taught for many years at the Philippine Military Academy before he retired. Peralta never received compensation for his war service despite repeated follow-ups. He is the uncle of Inquirer columnist Ma. Ceres P. Doyo.)

With wife Ma. Luisa and 9 children in the 1960s.