Portrait of History as a Filipino Family

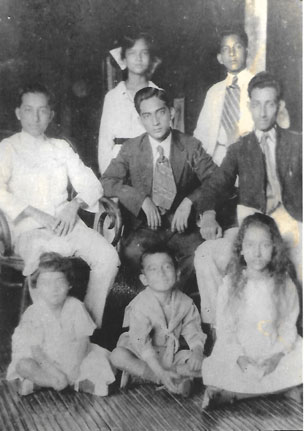

/The clan of Felipe Tempongko and Leocadia L’heritier at Pulong Mayaman, Malate, in 1934. The family patriarch is shown in the center, third row, with his wife to his right. Surrounding him are his children, some of their spouses and the nine grandchildren who had been born by then.

Pulong Mayaman, literally translated as Rich Island, was an enclave situated on Vermont Street and San Marcelino, behind Philippine Women’s University on Taft Avenue. The place, however, was neither an island nor an enclave of wealthy people when the Tempongkos lived there during the years of President Quezon. One may speculate on the meaning it may have had in pre-Hispanic times, whether it may have been inhabited by wealthy natives or was environmentally bountiful.

Felipe Tempongko, who is seated on the third row from the bottom with his wife, Leocadia on his right, was originally from Binondo. He was the son of Ambrocio Tempongko, a shipping broker and agent, and Inez Calixto. Both were of solid Manila families; to this day, there are Tempongkos from another branch who live in Tondo. Inez Calixto, whose daguerreotype miraculously survives in a cameo image, was descended from Spanish and Chinese forbears.

As a young man, Felipe Tempongko studied at the fencing school of the Luna brothers on Iris/Azcarraga streets. He imparted his knowledge of this sport to his younger sister, Elisea, and his daughter, Esther.

Inez Calixto, wife of Ambrocio Tempongco (pictured on the left), was the grandmother of Esther Tempongko y L’heritier, daughter of Felipe and Leocadia Tempongko (on the right).

This remarkable likeness of her was preserved on a cameo inherited by latter-day Tempongkos.

Leocadia L’heritier was the daughter of a French businessman who emigrated to the Philippines as a young man at the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Her mother was Francisca Vera, a feisty India-Filipina entrepreneur whose business was sponsoring boxers for prize matches. It was not a happy union. When the Philippine Revolution broke out, Antoine L’heritier moved back to France and arranged for his daughter Cadia to study and board at the La Concordia convent endowed by Margarita Roxas de Ayala. It was there where Leocadia would meet her future sisters-in-law from the Tempongko family. Some of Jose Rizal’s sisters also studied at La Concordia, which is why Leocadia herself was able to glimpse Rizal himself during one of his visits.

The Tempongkos were a typical bourgeois family living in the bustling business district of Binondo, sometimes regarded as the Paris of the Orient and deemed to be the precursor of today’s Makati. They socialized in the circles of such families as the Ongpins and the Yuchengcos , who belonged to the Hispanized Chinese gremio that had populated the Chinese Parian of Binondo.

The older son, Felipe, studied at the San Juan de Letran in Intramuros and fought as a foot soldier in the army of Emilio Aguinaldo in the second phase of the Philippine Revolution, the war against the Americans. As a young man, he studied fencing at the school of Juan and Antonio Luna on Calle Iris off Azcarraga (the later Claro M. Recto Street). He would pass on this art to his sister, Elisea, and to his daughter, Esther. He joined the Oriental Lodge of the Philippine Masons, where he reached the 33rd degree. His younger brother Clodualdo was among the first graduates in 1911 of the University of the Philippines College of Agriculture. Clodualdo (Dondoy), who had a promising future, unfortunately, died young and unmarried.

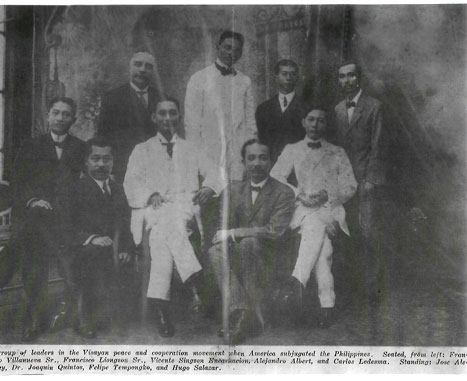

The Tempongko family witnessed the crucial transition between the end of the Spanish era and the beginning of the American one. After being briefly imprisoned by the Americans for having fought for President Aguinaldo, Felipe Tempongko became part of the consultative committee established by the new American colonizers for the purpose of establishing peace in the Visayas.

In the top row, Felipe Tempongko (second from the right) and, to his right his future brother-in-law, Dr. Joaquin Quintos (who became the husband of Demetria Tempongko, Felipe’s sister), were fellow members in the U.S.-organized consultative committee called “the Visayan peace and cooperation movement.” Other members included such dignitaries as Vicente Singson Encarnacion, Alejandro Albert and Carlos Ledesma.

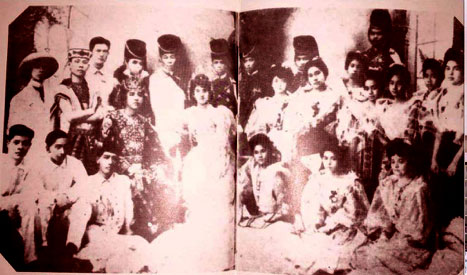

The Americans also sought reconciliation with disgruntled Filipino rebels through the spectacle of the Philippine Carnival, a version of the New Orleans Mardi Gras. Felipe Tempongko’s younger sisters, Elisea and Purificacion, were in the court of honor of the first Philippine Carnival Queen in 1908, Pura Villanueva (later Kalaw). Their brother Clodualdo was among her escorts. His sisters, Agapita(Pitang), Elisea(Cheang), Cristina(Tinay), Demetria(Metiang) and Purficacion(Chong) would later marry, respectively, into the Magpayo, Macapinlac, Ongpin, Quintos and Roco clans. They were lively young women, some of whom would sneak off to the rooftop azotea to sneak a smoke away from the prying eyes of their parents and helpers. Among themselves, they spoke a Manila patois called lengua de tienda, although they could also speak the straight Spanish taught in Manila schools. Their favorite game was panguingue, a card game that woul regale and unite them until they were in their eighties.

Felipe Tempongko (who changed the spelling of the family’s surname from the more Chinese Tempongco to the Filipinized Tempongko) followed his fathers footsteps by working as an accountant or contable at the famed La Estrella del Norte shop on Escolta street.

At the first Philippine Carnival of 1908, Elisea and Purificacion Tempongko (second row, 3rd and 4th from right) and their brother, Clodualdo (second row, leftmost) were in the court of honor of the Queen Pura Villanueva (later Kalaw).

Felipe and Leocadia had a large, healthy brood of nine--Fernando, Umberto, Carlos, Ernesto, Esther, Sarah, Antonio, Oscar and Lydia. With Spanish and Tagalog as their home languages, they soon learned English in school as part of the new dispensation. Musically gifted, the older boys formed a band and frequented balls where they could squire damsels. They were also mechanically inclined, which is why they started the family businesses of gasoline stations and car repair shops. They were the family chauffeurs, happily driving their father to his work at the Estrella del Norte, or their mother to La Quinta in Quiapo for marketing.

Eight of the nine children of Felipe and Leocadia Tempongko (first row, left to right), Lydia, Oscar, Sarah; (second row, left to right), Carlos, Umberto, Fernando; (top row), Esther and Ernesto. Missing from the photo is Antonio.

Esther continued her uncle Clodualdo’s tradition of studies at the University of the Philippines, where she finished her Associate of Arts degree majoring in English before she married Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara. Esther and her sister Sarah were known on the U.P. campus in Padre Faura for their thespian skills as well as for their bravado in sports—fencing in Esther’s case and sharpshooting in Sarah’s.

Having finished an Associate of Arts degree majoring in English at the University of the Philippines, Esther Tempongko married her mentor, Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara of Capiz in 1925. They were later to have three children—Erlinda, Vilma and Aurora.

Sarah Tempongko (later de la Paz) and her cousin Flora Tempongko Ongpin (later Heras) were the first models of the venerable Camera Club of the Philippines.

Antonio and Oscar both finished dentistry and all three sisters became schoolteachers at some point of their lives. Their work ethic and business acumen served them in good stead during the Japanese Occupation and the Second World War. While Oscar and Antonio became part of the guerrilla movement, their brothers ran coffee shops or engage in trading to help their families survive. When her doctor husband was stricken ill by a stroke, Esther supported her family by baking cakes which she sold at her aunts’ café. At war’s end, she had saved as much as eight hundred dollars in reliable Yankee currency.

The Tempongko clan was to fully experience the brunt of the Second World War when their houses in South Manila were subjected to Japanese atrocities and American bombing. Their mother, Leocadia, prayed that should anything happen to her clan, she should be the one to suffer and, indeed, she was hit by a shrapnel that killed her after weeks of horrific agony. Miraculously, no one else in the clan was even wounded during the destruction of Manila.

The long saga and history of the Tempongko clan is a mirror of the variegated history of Manila and the Philippines. Through this brief history of one Filipino family, one may gather intriguing insights into the evolution of Philippine society in the 120 years since the Philippine Revolution. Theirs was a story that could give grist to the mill of a latter-day Marcel Proust. Pulong Mayaman, indeed!

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He is now engaged in writing, traveling and is dedicated to cultural heritage projects.

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.