Political Dynasties Disable Philippine Democracy

/This is part 2 of a series of articles on the Philippine electoral system.

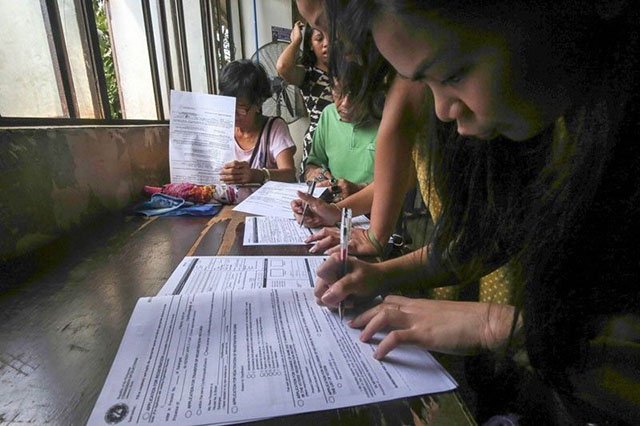

New Filipino voters register (Source: Comelec/facebook)

U.S. Background

The initial objections to a political dynasty stemmed from a general dissatisfaction with the British monarchy. The American founding fathers were against the abusive King George III who over-taxed the colonies to fund his lavish lifestyle. Many loathed the concept of “blue blood” divine rights and entitlements and believed that positions of leadership are derived from the people and should be used to serve them.

Hence Article I, Section 9, Clause 8 of their 1789 Constitution provides that “No title of nobility shall be granted by the United States.” A counterpart provision is found in Article VI, Section 31 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution.

Yet, Americans do not generally frown upon dynasties. In fact they treat them as political royalty whose heirs are expected to preserve the family honor and pursue long-term development-oriented strategies. Dynasties work in the U.S. because open competition and institutional checks and balances ensure that no group can dominate the political conversation.

The first dynasty started with John Adams who was elected the second President of the United States while his son, John Quincy Adams, was the 6th. Over the years, the more prominent families that evolved into strong political brands were the Roosevelts, the Kennedys, the Bushes, and, if the 2016 presidential elections went the other way, the Clintons. Not as well-known are the Bayards of Delaware (six generations of U.S. senators) and the Breckinridges of Kentucky (a vice president, two senators, and six representatives.)

Philippine Setting

To confront our feudal past and combat patronage politics, the framers of the 1987 Philippine Constitution introduced a new Article II, Section 26: The State shall guarantee equal access to opportunities for public service, and prohibit political dynasties as may be defined by law.

There have been various attempts in the last 30 years to enable this constitutional prohibition. Unfortunately, these efforts have been in vain. The executive and legislative branches of government have not been able to muster the political will to go against a vainglorious self- interest to pass a defining law that would serve the national interest. It is only in the Sangguniang Kabataan (youth council) where a prohibition exists. Section 10 of R.A. No. 10742 forbids individuals from seeking a youth council position if related within the second civil degree of consanguinity or affinity to any incumbent elected national official or to any incumbent elected regional, provincial, city, municipal or barangay official in the same locality.

In his 2015 State of the Nation address, President Benigno Aquino III became the only sitting chief executive to urge the passage of an all-encompassing anti-political dynasty law. That call also fell on congressional deaf ears.

That political clans are lording it over the country’s 81 provinces, 146 cities and 243 Congressional districts is a political given. Noted political scientist Richard Heydarian estimates that between 70 percent and 90 percent of elected offices are now controlled by dynastic families.

Their influence has permeated into the party list system which was originally envisioned to provide a Congressional voice for the marginalized and underrepresented sectors of society. Of the 134 party-list groups that participated in the May 2019 midterm elections, at least 62 had ties to influential families. Of the 270 party-list groups that filed their Certificates of Candidacy for the May 2022 elections, a majority is controlled by political dynasties.

Clan influence is also seeping through the usually independent Senate. Judging by the latest survey results for the senatorial hopefuls in the upcoming May 2022 elections, there is a high probability that eight out of the 24 senators will be related parties- either parent/child (Binays and Villars) or sibling/sibling (Cayetanos and Ejercito/Estrada). If we count the almost father/son relationship of President Duterte and Senator Bong Go, that raises the number to 10. If Sarah Duterte is elected Vice President, she would be backed by these two senators. And if Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. wins the presidency, he would have a Senate ally in elder sister Imee Marcos. The cartelized executive and legislative branches of government will be “an all in a few families” affair.

The Cayetanos: Senator Pia Cayetano, former Mayor of Taguig Lani Cayetano and Rep. Alan Peter Cayetano, current Mayor of Taguig Lino Cayetano

Former senator Jinggoy Estrada, Former president and former mayor of Manila Joseph Estrada, former senator JV Ejercito and San Juan Vice Mayor Janella Ejercito-Estrada

The Binays: former Vice President Jejomar Binay, Senator Nancy Binay, former Makati Mayor Jejomar Erwin Binay, Jr., current Makati Mayor Abigail Binay

The Villar Family: Manuel Villar III, Senator Cynthia Villar, Former Senator Manuel Villar, Jr., Rep. Camille Villar and Dept. of Public Works and Highways Sec. Mark Villar (Source: Tatler/facebook)

President Rodrigo Duterte with children, Veronica Duterte, Davao City Vice Mayor Sebastian Duterte, Vice Presidential candidate and Davao CIty Mayor Sara Duterte Carpio and Rep. Paolo Duterte (Source: Reuters)

The Marcos Family: Congressional candidate Sandro Marcos, Presidential candidate Bongbong Marcos, former First Lady Imelda Marcos, Senator Imee Marcos, Irene Marcos-Araneta, Borgy Manotoc, Ferdinand Reginald Michael Manotoc, and Ilocos Norte Gov. Matthew Joseph Manotoc. (Source: Imee Marcos/Facebook)

While there seems to be a negative perception of political dynasties at the national level there is a more positive regard in the local governments. This is understandable given the socio-economic realities upon which clan politics are built and the culture of dependency and apathy it has spawned.

The vicious cycle is about to be repeated. Because of a high incidence of poverty, many Filipinos are beholden to their local leaders. Money is invested not only during the campaign but for KBL (not the political party formed during Martial Law) -- Kasal (marriage) Binyag, (baptism) and Libing (funeral). There is another L- Lamay (wake) where the tents and tarps bannering the sponsoring politician’s name are loudly displayed. By encouraging a habit of clientelism, utang na loob (debt of gratitude) and loyalty are nurtured and translated to votes on Election Day.

The debilitating effects of dynasties on Philippine society are well-documented.

In their study entitled The Effect of Political Dynasties on Effective Democratic Governance: Evidence From the Philippines, U.S. researchers Rollin F. Tusalem and Jeffrey J. Pe-Aguirre found:

“Provinces dominated by family clans are less likely to experience good governance in terms of (a) infrastructure development, (b) spending on health, (c) the prevalence of criminality, (d) full employment, and (e) the overall quality of government. The implications of the empirical analyses convey that political dynasties have deleterious effects in terms of the allocation of public goods, even if their presence induces higher levels of congressional earmarks.”

“Noted political scientist Richard Heydarian estimates that between 70% and 90% of elected offices are now controlled by dynastic families. ”

Vote As Prayer

I harken back to Thomas Jefferson’s well-worn cliché - The government you elect is the government you deserve. Fast forward 200+ years to the wise words of the new Senator from Georgia, Rev. Raphael Warnock: “A vote is a kind of prayer about the world you want to live in.” May our votes reflect the mature and responsible electorate that we can be, and enable democracy.

Andy Bautista obtained a LL.B.degree (class valedictorian) in 1990 from the Ateneo School of Law and a LL.M. in 1993 from Harvard Law School where he served as a research assistant to Professor Laurence Tribe. He taught Constitutional Law for over 25 years.

More articles from Andres D. Bautista