Please Stop Calling the Philippines ‘P.I.’

/P.I., of course, means Philippine Islands, and to most Filipinos familiar with the U.S. colonization of the Philippines, it is a politically incorrect term. This much I learned from my U.P. history professor Dr. Oscar Alfonso.

P.I. as a term is specific to the Philippines as U.S. territory, a colonial one, until the U.S. Congress granted Philippine independence in 1945. The use of P.I. is an innocent mistake given that Philippine Islands is a direct translation of Islas Filipinas in Spanish, the name Spanish explorer Legazpi in 1543 gave to the group of islands (Leyte and Samar) in honor of the Felipe II, King of Spain.

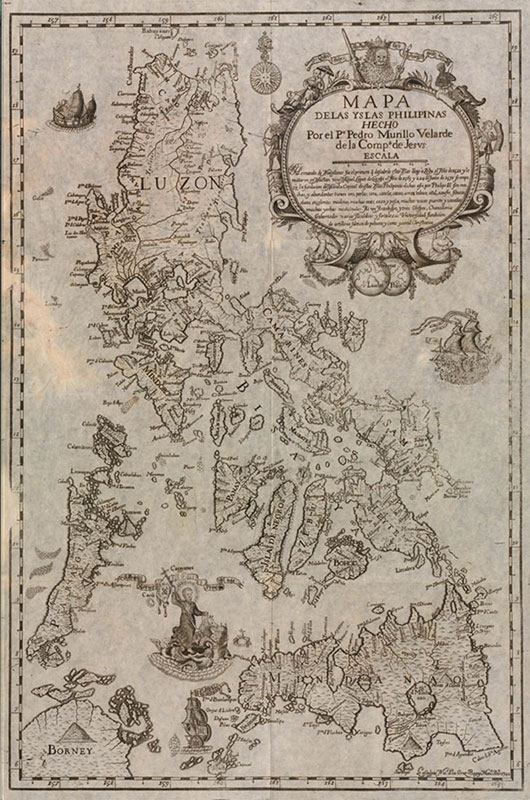

Las Islas Filipinas (Source: Three Hundred Years of Philippine Maps, 1598-1898)

Subsequent European travelers to the Philippines either called it by its Spanish name, Las Islas de Filipinas or simply Manila. An 18th century Italian map named the country, Isole Filipino, complete with drawings of an Italianate coastline. In other words, the European world saw the Philippines as the eastern-most extension of the Hispanic/European culture.

British travelers recognized the Philippine islands but considered only Manila and Cavite as the core of Hispanic society, a jewel of Asia. The British occupied Manila for two years as a prize for defeating Spain in the Seven Years War only to find out that the alleged wealth of Manila was in the galleon trade. It made the Spanish residents wealthy, but left the natives with nothing better than subsistence living.

In fact, the Philippines existed in the imagination of Europe only as the origin of the Manila-Acapulco trade. Mexicans of Nueva Espana ignored Manila altogether and called the trade Nao de China (Ship from China). Even then, Spanish Filipinas was effectively concentrated only in the coastal populations of Manila-Cavite, Ilokos, Cebu-Iloilo and Zamboanga.

During the Propaganda Movement and the Katipunan Revolution, to remove the odious label of “indio” -- the term the Spanish reserved for the natives -- the need to re-identify the Philippines became foremost in the minds of its leaders. While acknowledging the geography of the Philippine archipelago, what to call the multiplicity of linguistic cultures that existed then was problematic. Rizal’s contemporaries, ilustrados and scholars, toyed with the idea of a Tagalog civilization. Bonifacio ultimately declared the Katipunan as the revolt of the bayan katagalugan, the nation of many peoples in the Philippine archipelago. Aguinaldo upped the idea of a nation by declaring the independence of the Republica Filipina. Republic of the Philippines or R.P. eventually became the international identity of the independent Philippines.

The Katipuneros (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Unfortunately, the life of Aguinaldo’s R.P. was short-lived. Against the imperialist ambitions of the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century, the Philippines was recast as another political entity within the American Pacific empire. H.I. or Hawaii was annexed as well as P.R., Puerto Rico. The Philippines followed suit as P.I. Even as Aguinaldo was battling the U.S. Army during the Philippine American War (1899-1913), commercial and military communication already signed off their correspondence as P.I. -- Philippine Islands. There were vivid markers of this colonial identity in coinage, emblems and currency, not to mention maps.

The term “P.I.” today is reminiscent of the former colonial status of the now independent nation, and people who don’t know this background might be forgiven for their lack of historical accuracy. To persist in using it uncritically, however, is to insistently imply that the Philippines is still a U.S. colony. “P.I.” might as well mean Politically Incorrect.

On a final note, the Philippines is perhaps one of the few nations that still carry their colonially ascribed names (New Zealand, Micronesia come to mind). There have been proposals to change the Philippines’ name but without success: Rizalia (after Jose Rizal); Luviminda (Luzon-Visayas-Mindanao); Ma-i (Chinese name for Mindoro and Palawan; but let’s be careful lest China claims it as its territory); or Maharlika (nobility; but it also means potent male organ in Malay).

I guess our politicians gave up the idea of a name change because it’s too complicated and intellectually challenging. Or perhaps we need to change the society first before we can rename it.

Dr. Michael Gonzalez has degrees in History, Anthropology, and Education. A professor at City College San Francisco, he teaches a popular course on Philippine History Thru Film. He also directs the NVM Gonzalez Writers' Workshop in California. http://nvmgonzalez.org/writersworkshop/index.html