Playing the Assimilation Game

/First published in the Washington Post, September 6, 2017 with the title “Elaine Chao is Sticking by President Trump. That Shouldn’t Be a Surprise.”

Secretary Elaine Chao (SOurce: Getty Images)

But Chao’s apparent willingness to turn a blind eye shouldn’t surprise us. Asian Americans have persistently confronted discrimination, exclusion and even violence. But they have also heard promises that they could dodge this discrimination by buying into whiteness via assimilation. Both white and Asian Americans have posited that such a strategy would lead to socioeconomic gain and Euro-American approval, and therefore shield them from American racism.

But this idea has failed to come to fruition. Assimilation has its limits and doesn’t guarantee these protections.

This ideal, rooted in the romanticized belief that immigrants and people of color can be “just American,” has provided optimism to the masses since the turn of the 20th century. But rather than creating meaningful opportunity, it obscures the political, social and economic forces that created and continue to sustain racial inequality by placing blame on minorities for their plight. Pressuring Asian Americans and other minorities to assimilate conveniently removes pressure from white Americans to acknowledge histories of structural racism and keeps alive the idea that everyone begins from the same starting point. Moreover, assimilation allows whiteness to remain at the center of what we consider respectable citizenship.

Grappling with assimilation is part and parcel of the Asian American experience. For instance, during the U.S. occupation of the Philippines between 1898 and 1946, President William McKinley promoted an agenda of “benevolent assimilation.” It was the United States’s responsibility to “civilize” Filipinos as new subjects of the American empire. From implementing Western medical practices to making English an official language in 1935, many Filipinos were convinced that following these orders would modernize their country. Similarly, during the 1890s and 1900s, hundreds of Chinese men and boys in San Francisco discarded a tradition dating to the Qing Dynasty by cutting their pigtails and donning American attire to prove a willingness to embrace Anglo-American norms.

Social pressures to assimilate carried well into the 20th century, but it was not just a narrative forced upon minorities by white leaders. One contemporary Asian American figure who embodied and championed the assimilationist ideal was educator-turned-Republican senator S.I. Hayakawa, a Japanese American. Months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which banished Japanese Americans to internment camps. Even though two-thirds of Japanese Americans were born in the United States, all were stripped of their civil liberties and encouraged by the federal government and the Japanese American Citizens League to let go of native Japanese customs.

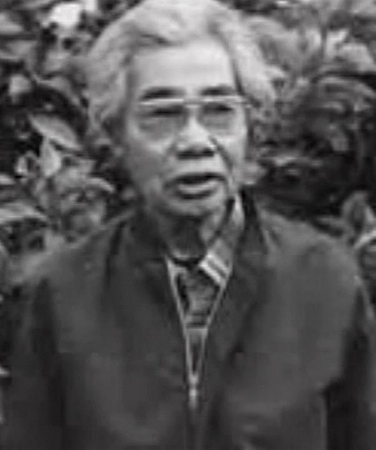

Senator S.I. Hayakawa (Source: Los Angeles Times)

Hayakawa escaped internment since he was a Canadian citizen during the war. Yet he later argued that internment was “perhaps the best thing that could have happened” to Japanese Americans, since it forced them to integrate. He also claimed reparations for the experience were unnecessary.

In 1955, Hayakawa joined the faculty at San Francisco State College (now university). As the counterculture movement of the 1960s percolated, student demands for Ethnic Studies departments and classes also intensified. Hayakawa formed the Faculty Renaissance Committee, a “traditionalist” group of scholars opposed to “radical” pedagogies and disciplines.

Unlike other people of color who agitated for basic rights and access throughout the civil rights movement, Hayakawa believed in meritocracy, assimilation and law and order. A rising star in the conservative movement, Hayakawa was, in many ways, the right’s poster child against anti-assimilationists of the period such as Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party and the pro-Chicano group, Brown Berets. While some Asian American activists such as Yuri Kochiyama, Grace Lee Boggs and Philip Vera Cruz worked across racial lines demanding social and economic justice, Asian Americans like Hayakawa dismissed their views as out of touch or atypical among Asian Americans.

Yuri Kochiyama

Grace Lee Boggs (Source: NPR)

Philip Vera Cruz

In 1968, then-Gov. Ronald Reagan appointed Hayakawa as acting president of San Francisco State College. Hayakawa criticized a coterie of black, Latino and Asian American ethnic nationalist organizations collectively known as the Third World Liberation Front. Unlike Hayakawa, who believed in the system, radical activists questioned authority and called for a global end to imperialism, capitalism, militarization and white supremacy. Hayakawa dismissed such demands as unrealistic and counterproductive toward minorities’ progress.

Hayakawa’s actions suggested that he was hostile toward the interests of people of color. This, however, is an oversimplification. Hayakawa fiercely advocated utopian ideals of assimilation not out of hostility, but because he believed that buying into the status quo would result in mainstream acceptance and the upward mobility of his fellow Asian Americans. From the vantage point of Hayakawa’s contemporaries, letting go of ethnic traditions would warrant those privileges.

To some degree, Asian Americans of his and subsequent generations made their way into the middle class by making those concessions. But oftentimes that investment in whiteness via assimilation also meant aligning against the interests of Asian Americans as well as other minorities. It also represented a blindness to the experience confronting his fellow minorities.

Former Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal, an Indian American, has embraced the same theories as Hayakawa in the 21st century. Long before Charlottesville, Jindal was in the middle of the New Orleans debate over whether Confederate symbols should be publicly memorialized after the Charleston church shooting by white supremacist Dylann Roof. Pressured by conservative constituents, Jindal vowed to prevent the removal of these statues to appease fellow Republicans who argued that the statues were symbols of “heritage, not hate.” Like Hayakawa, Jindal’s pandering to white conservatives demonstrated his willingness to abide by the force of assimilationist politics, or — as some would suggest — a desire to maintain Asian Americans’ mythic status as “model minorities.”

Gov. Bobby Jindal (Source: Washington Times)

Hayakawa and Jindal were likely responding to the rhetoric Asian Americans heard then and still hear now: Assimilation will dissolve inequalities and move the country toward racial harmony. In a related way, some Asian Americans have also heeded the right’s calls for meritocracy, believing affirmative action works against their interests despite a segment of working-class Asians who benefit from these programs.

While these strategies and beliefs might have helped Asian Americans like Hayakawa and Jindal ascend to power, most people of color face glass ceilings and racial barriers. Studies show that despite their efforts to assimilate and despite perceptions of Asian American success, Asian Americans continue to experience discrimination and deal with various forms of inequality.

Over the past century, assimilation has served as a distraction and a tool to inhibit political mobilization among people of color. Since the 1840s, bigotry has been a fundamental part of the Asian American experience and one that has not been remedied by adjusting to plain-folk Americanism. Moreover, for Asian Americans like S.I. Hayakawa, Bobby Jindal and Elaine Chao, their actions could be read as endorsements of anti-blackness. Buying into whiteness via assimilation not only potentially pits Asians against other people of color, but it also keeps alive the idea that assimilation is the primary means of earning freedom and achieving racial harmony in America.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of this publication.

James Zarsadiaz is an Assistant Professor of History and the Director of the Yuchengco Philippine Studies Program, University of San Francisco.