Philippine Echoes of Spain’s Civil War

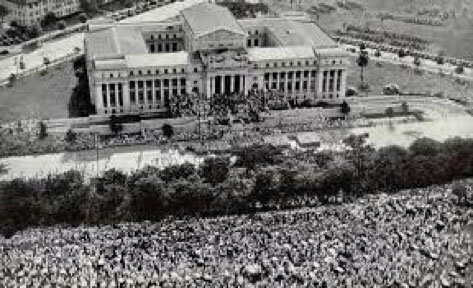

/The inauguration of the Philippine Commonwealth on 15 November 1935. The building is now part of the National Museum of the Philippines.

President Manuel L. Quezon at the inaugural of the Philippine Commonwealth. Fluent in both Spanish and English, he also promoted Tagalog as the basis of the National Language.

The Casino Espanol on Taft Avenue, designed by Architect Juan Arellano, was the foremost social club in Manila. “Peacetime” is reflected in the abundant greenery on this premier street.

A strong Hispanic influence still prevailed in the country, personified by the mestizo President Manuel L. Quezon himself and his elegant family. The Casino Español on Taft Avenue was Manila’s toniest social club. Tabacalera and Cerveceria San Miguel were well known brands run by Filipino-Spanish businessmen. The lingua franca was still Castilian throughout the islands; moreover, it was employed in the courts and in the halls of Congress, as by newspapers, periodicals, and films. English was still making inroads into this dominance, and Tagalog had just been decided upon as the basis of a National Language.

It was but natural that the Philippines would take a profound interest in Spain, where both a rebel army and the Catholic Church opposed a duly elected Republican Government and would play major roles in a horrific civil conflict, which would prove significant for Europe and the world in the years following its conclusion in 1939.

The San Agustin Church is the oldest colonial religious structure in the Philippines and survived the holocaust of the Second World War. Miguel Lopez de Legazpi is buried in this church.

The Philippines was a freshly minted republic-to-be, which embraced democratic and republican principles. However, for 333 years it had been ruled by representatives of the Spanish monarchy and dominated by the Catholic Church. The Spanish community in Manila was divided between those who supported the secular Republic and others who sided with the rebel forces of Generalissimo Francisco Franco.

There was a Falangist party in the archipelago, the Spanish National Assemblies of the Philippines (Juntas Nacionales Española), a branch of the Spanish Falange. It was founded in 1936, included wealthy and prominent Spanish Filipinos as members, and sent aid in various forms to Franco’s nationalists in Spain.

To this day, there is a street in Makati named Yague, after a Spanish officer of the Civil War.

In fact, the insecurity of Spain in early twentieth century had stemmed from the loss of its last colonies—Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam—which it had surrendered upon indemnity of $20 million by the new emerging imperial power, the United States of America. It called 1898, El Desastre or The Disaster.

Spain’s King Alfonso XIII (grandson of Queen Isabela II, who had reigned over the Philippines) had reached majority in 1902, and in his last years as king, ruled with a military dictator, General Miguel Primo de Rivera, from September 1923 to January 1930. The Spanish army had always interfered in the affairs of state throughout history, and coup d’etats or pronunciamientos were not unusual for Spain. While parts of Spain had been industrialized, others remained backward and rural, where landlords and the Church dominated.

Fernando Primo de Rivera

The Marquess of Estela, Fernando Primo de Rivera (1831-1921), was one of the last Spanish Governors-General in the Philippines, whose administration agreed with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato.

In a historical footnote, Primo de Rivera’s uncle Fernando (the Marquess of Estela) had been one of the last Governors-General in the Philippines and was the forbear of Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, who was killed during the Civil War and promoted by Franco later as one of the martyrs of the Nationalists, as the rebels termed themselves. It was the Government of General Fernando Primo de Rivera who had negotiated the Pact of Biak-na-Bato with General Emilio Aguinaldo in San Miguel, Bulacan in 1897, in a last bid to prevent the further spread of the Revolution.

In Spain, the municipal elections of 12 April 1931, became a referendum on the monarchy itself. When the results decisively repudiated the monarchy, Alfonso XII (great grandfather of the present King Felipe of Spain) went into exile on 14 April 1931.

A new Constitution was passed on 9 December 1931, which defined Spain as a “democratic Republic of workers of all types, (which is) organized under a regime of liberty and justice,” it declared the secular nature of the State, did away with State financing of the clergy, introduced civil marriage and divorce, and banned religious orders from teaching.” It also granted the vote to women.

The Second Spanish Republic was initiated in April 1931 and survived till April 1939.

This ran counter to the long-lived monarchist order, which had not known any official religion in the modern era other than Catholicism, and which had only experimented with Republicanism briefly in the early nineteenth century. Rizal and members of the Propaganda movement had interacted with members of the liberal democratic groups such as Francisco Pi y Margall, President of the First Spanish Republic of 1873-74, and Miguel Morayta (after whom streets were named in the University Belt in Manila). Masonry was popular among the ilustrados and helped form the rites of the Katipunan and been a force within the Philippine Revolution of 1896-98.

The two Spains—one of liberal democracy/socialism and the other, of an authoritarian/autocratic/ religious State—wrestled within the same nation. Spain had not participated in the First World War and thus did not suffer the political upheaval, or the loss of monarchy. In fact, Fascism and Communism—the fruits of that conflagration—had not yet appeared in Spain.

The first five years of the Second Spanish Republic were relatively successful, except for the determination of the conservative forces to consider extraparliamentary means to obtain power. This could be termed a “democratic space” similar to the post-EDSA Philippines of 1987, which was also menaced by coup d’etats.

It was a time of euphoria as well as literary and artistic ferment, which produced such luminaries as Bunuel, Lorca, Picasso, and Dali.

Caught in this productive artistic environment was a Filipino-Spanish writer, Adelina Gurrea, who had migrated back to Spain from the Philippines. She had graduated from St. Scholastica’s College in Manila and wrote for such Filipino-Spanish publications as La Vanguardia and Excelsior.

Adelina Gurrea (1896-1971) was a Filipino-Spanish writer who represented her country of origin in Spain through her poetry and activism during the Republican and the Franco years.

Gurrea was active in the women’s movement and recognized in the Spanish press and literary circles for her talent. Speaking both Spanish and Bisaya (since she had grown up in the Visayas), she represented women’s liberation and avant-garde approaches. In fact, she was a lesbian and unabashedly had female lovers. With Franco taking power in Spain, her children’s stories, coming under the rubric “Cuentos de Juana” became her means of earning a living and postulating unorthodox ideas in the guise of foreign children’s tales from the Philippines.

Yet, such literary and artistic experimentation would be threatened by far greater forces than could be imagined and that would bring about Spain’s greatest nightmare.

Factions of the Spanish military, including Generals Jose Sanjurjo, Emilio Mola and, crucially, the caudillo Francisco Franco who was based in the Canary Islands, had never reconciled themselves to the Republic. The assassination of Jose Calvo Sotelo, a rightwing monarchist leader, by members of the Republican police force on 13 July 1936 was the cause de guerre for a long-brewing plot against the Republic.

On 18 July 1936, Franco declared a state of war against the government of the Republic and began his invasion from Morocco, with well-planned uprisings throughout Spain. In the words of author Julian Casanova: “The military uprising of July 1936 forced the Republic, a democratic and constitutional regime, to take part in a war it had not begun.”

By rights, the Republic should have prevailed since in the beginning; it had controlled the Treasury, the bureaucracy, most of the territory and industries and enjoyed the support of a great majority of the people. But with the defection of the army and with only voluntary militias to rely on, the Republic was at a great disadvantage. The heroism of its defenders emerged in the stories of George Orwell (“Homage to Catalonia”) and Ernest Hemingway (“For Whom The Bell Tolls”), who volunteered to serve in such bodies as the Lincoln Brigade.

In contrast, Franco’s highly trained forces and unwavering support from Hitler and Mussolini enabled him to gain ground over a period of three years.

On the other hand, democracies such as the United Kingdom and France had adopted a noninterventionist policy (not respected by Germany and Italy), which prohibited them from exporting arms and intervening in the Spanish civil war. This had the net effect of driving the Spanish Republic into the arms of the Soviet Union, whose support could not match those of Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy for Franco’s troops.

The Spanish civil war saw the first aircraft war waged against civilians, as was memorialized in Picasso’s immortal painting of Guernica.

“Guernica” by Pablo Picasso

The iconic “Guernica” by Pablo Picasso reflected the savagery and cruelty of the Spanish Civil War in the bombing of civilians by air in the Basque country. It was transferred from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the Museum of Queen Sofia in Madrid, as pledged by the artist upon restoration of democracy in Spain.

It evolved into a religious crusade for the Catholic Church, which viewed Franco as a quasi-saint and defended him at the highest levels through episcopal letters. The Spanish Civil War was also the first internationalized war of the 20th century, with atrocities committed by both sides unable to accept compromise.

Appeasement having been the tool used by the Western countries towards Hitler and Mussolini, it was not long thereafter in 1939 that the United Kingdom, France, and their allies would be threatened and then overwhelmed by the very forces that they had sought to ignore in the Iberian peninsula.

For the Philippines, the rise of Japan as an Axis power would be a direct result of the victory of Franco’s government in Spain. In 1941, year in which the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Manila, the Philippines had not yet completed its American apprenticeship. It had not yet achieved full independence or possessed the sovereignty to declare itself neutral.

The Philippine Commonwealth was, in effect as vulnerable as the Second Republic in Spain. It did not have adequate military forces or preparation to defend itself. Its principal democratic defender, the United States of America, withdrew its remaining command to Australia and the mainland.

Though Spain’s Civil war was an internal conflict and the Philippines was invaded by foreign forces, the effects of these respective wars were deep and far-reaching in both societies. Both Spain and the Philippines were to experience decades of authoritarian rule in the postwar era.

Intramuros, annihilated in the Second World War, has been partially rebuilt in the postwar era.

The Philippine ordeal of 1942-1945 would be a brutal echo of the carnage that occurred in Spain in 1936-39. By 1945, Intramuros—the shining symbol of 333 years of Spanish presence in the Philippines—would be demolished by aircraft and fire, ending in scenes strangely similar to those of Guernica.

Note: For reference, see Julian Casanova, “A Short History of The Spanish Civil War, Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2017.

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He is now engaged in writing, traveling and is dedicated to cultural heritage projects.

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.