Oh How I Miss Manila Mahjong

/Ah, the inimitable sounds and smells from the mahjong (or mah jongg, or even Maahj) parlors of Manila. Mahjong would seem to be the purview of ladies of leisure in the Philippines, or wherever else it is played around the world, indulged in by all socio-economic classes. It’s a pastime that transgresses the boundary between leisure play and full-scale gambling.

A typical foursome at play, doing the Chinese-version.

I grew up playing mahjong, or rather my parents, aunts, uncles, neighbors, and their circle played mahjong quite regularly that, by osmosis, I also learned and appreciate the finer points of the game. While the family played for money, however, it was not for very high stakes, just enough to make it enjoyable and worthwhile to spend a whole afternoon on.

So ingrained was the culture of mahjong in our lives that, one year, I remember we even had a birthday cake made for Mom (similar to photo below). Country Bake Shop on Isaac Peral made those really, uniquely-designed and beautiful cakes.

For those unfamiliar with the game, mahjong is essentially an off-shoot of (gin) rummy, or contract bridge, or vice-versa. It is usually played by four people. However, the main difference between bridge and mahjong is that in bridge, your partner and you play and set up your contract as a team. In mahjong, you play and strategize (create a contract or template) for yourself, making it one against three.

To win by declaring mahjong, a player tries to complete subsets of either three of a kind, a sequence run (e.g., 3-4-5 clubs or sticks) or various combinations thereof, to compose a winning hand.

History of the Game

Like fireworks and the compass, mahjong was invented in China, and its similar composition to a deck of cards (four suits, running up to number 9) is no coincidence. Playing cards were also actually invented in old China. As far back as the 14th century, the four-suited playing card deck first surfaced in the west in Mameluke Egypt, brought over from ancient Cathay. From there, it worked its way up the Iberian Peninsula into Spain, France, then Italy, and the rest of the western world. The early version of Spanish playing cards (with the four suites of coins, cups, swords, and clubs) then came to the Philippines via Spanish rule.

(There supposedly is a Filipino card game similar to mahjong called pangginggue, actually, a Fil-Hispanic-originated card game. In my days in Manila, I had heard of it but was never familiar with it. I learned that a group plays it at the Elks Lodge in Alameda. So, for the first time in my 70 years, I came face-to-face with this old Filipino card game one giant ocean away from the homeland. I found out, however, that pangginggue is probably 60% similar to mahjong, but it’s very much a game of chance rather than strategy, which I think mahjong is ,so it’s something I don’t see myself cultivating.)

Back to old Cathay. The playing cards’ transformation to mahjong tiles may have occurred, as one version goes, when it might have been invented for Chinese royalty who played it in secret to keep the knowledge to themselves. Another story claims that a general devised the game to amuse his troops during the Taiping Rebellion of 1850-1864. But the one certainty seems to be is that it was conceived by persons with some high, mathematical sophistication given the myriad math combinations of the game.

Exquisite rendering of mah-jongg being played in an ancient Chinese setting.

Banned in Beijing

Towards the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th, with international trade reaching the four corners of the earth, the game found its way across the seas. Flash-forward to 1949 when entire mainland China became the communist People’s Republic of China. Mao’s early regime deemed the game as decadent capitalist, i.e., not conducive to building the new workers’ socialist paradise; hence, it was banned along with other gambling activities.

It was not until late into the Cultural Revolution of the early ‘70s that the game came back into favor. In 1985, mahjong became legal again in the land of its birth, and people began to play it in earnest once more. Finally, in 1998, mahjong achieved some sort of legal status by becoming the 255th(!) game to be recognized by the General Administration of Sport in China.

How many versions of mahjong are there?

By one online count, there are more than 20 versions, which include the various Asian editions (standard Chinese or Hong Kong, but each region in China has its own set of rules; Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, and western versions American, Australian, British, Canadian, French, German, Italian, etc.). And some of these are subdivided into traditional and modern versions. There is even an Asia/Pacific version that believe is a simplified version.

Surprisingly, that list does not include the Philippine (or Manila version, as I prefer to call it), which, like most facets of Chinese culture assimilated into contemporary Filipino culture, is a hybrid of the Hong Kong-style mixed with the Taiwanese version.

(For purposes of this article, permit me to use Manila-style mahjong rather than Filipino-style; and mahjong, the preferred Filipino usage. I feel “Manila-style” is more euphonious than “Filipino-style” and in the Philippines, the game became greatly popular in the salons of Manila which, as the capital and seat of everything else, always sets the trend for the rest of the country to follow.)

The Chinese version is, of course, the font and traditional version of the game.

Since I haven’t managed to find a compatible group locally playing Manila mahjong, I’ve tried to learn standard Chinese (also called Hong Kong) mahjong because that is what I found on Meet-up. I’ve since found many of its rules and conventions, however, to be very anal and OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder). For example, when building the walls, these have to be oh-so straight (eyeroll)each side has to be exactly 18(!) double tiles long. So much energy is spent trying to figure out who is “East,” “West,” “North,” “South,” but that “Wind” doesn’t necessarily throw the dice, that it becomes such a protocol-heavy and a joyless exercise.

Even among the most serious HK-style players, if you happen to touch the tiles intended for another player, this would be a major faux pas since you would then have jinxed those tiles! Such slavish obeisance to too many details, in my mind, bogs down the flow of the game (for the beginner) and almost constitutes a power trip for those who are more knowledgeable of the game.

If the Chinese version is bewildering and too anal, then I got something else coming if I wanted to play the Japanese, or riichi, or even referred to as the yakuza (gangster) version. An online YouTube lesson primer, granted it’s very thorough, runs over 3.5 hours –as long as The Ten Commandments film, but not as entertaining.

“Upper class Filipinas” engaged in a game of mahjong. This is a scene from the 1982 Filipino film, Oro, Plata, Mata. The actresses are (left to right) Liza Lorena (partial view), Lorli Villanueva, Mitch Valdes and Fides Cuyugan-Asencio (partial profile).

(Disclaimer: I had started this piece long before the movie, “Crazy Rich Asians.” I understand that the film, which I have no intention of seeing, has a pivotal scene involving mahjong. So the film did not in any way, influence this piece.)

From the Japanese version springs Korean-style which is even more different from Chinese mahjong. For starters, the sticks or “bamboo’ suite is completely eliminated, thereby entirely changing the dynamics of the game, making it better suited for three players. Since Korea was a one-time colony of Japan, the influence and elements of Japanese-style mahjong are quite discernable. And the game being a legacy of their one-time colonizer, Japan, doesn’t make mahjong a very popular game in Korea.

Right now, I am torn between the Chinese and American versions, which was supposedly introduced to the US in 1920 by wives of Jewish-American executives who did business in China after the fall of Manchu dynasty, and in the early days of the Sun Yat-sen regime (around 1907-1918), or in Hong Kong when it was still a British colony.

Originally, Abercrombie & Fitch (then a New York retailer of luxury sporting goods, expensive shotguns, etc., and other exotic items) carried the first mahjong sets in the East Coast. When their initial inventory sold out, A&F dispatched agents to China to buy all the mahjong sets they could find. (I am sure, however, that mahjong was already being played in the Chinatowns of San Francisco and New York, but stayed exclusively within those confines, never venturing out to the mainstream American populace.)

But the game became all the rage in the Roaring ‘20s with the white population, especially in the summer resorts of the Northeast, like the Catskills and Poconos, popular with Jewish American families. A&F supposedly sold as many as 12,000 mahjong sets in its heyday.

Like contract bridge and many American sports and pastimes, a national association was formed in 1937 to standardize the rules of the game in America. It was the National Mah Jongg League (NMJL)(notice how NMJL adheres to a different spelling of mahjong).

What makes American mahjong a little more manageable (even though there are 30 recognized ambiciones or winning patterns) is the crib sheet issued annually by the NML, listing new legal templates du jour or for the year. They cost $5; the plastic containers in which they come, cost $9 each. The reason for charging petty sums for the patterns and rules, is to generate funds for the governing body to at least be self-sufficient and solvent.

Manila-Style

Of course, the game’s entry into the Philippines is no mystery. It was brought over by immigrants from Canton/HongKong and Formosa (Taiwan’s pre-Republican name), hence the Taiwanese influence on the Manila version.

The hybrid Manila version plays with 16 tiles vs. 13 in the Hong Kong version, and it downplays the importance of the Winds, Flowers and Dragons, which are treated equally with the other suits in the Chinese. Manila-style also recognizes certain templates such as siete pares/seven pairs and chow de ter/end chows, not found in standard Chinese.

A “7 pairs / Siete Pares” hand, found in Manila mahjong. This is a template (ambicion) played only in Manila and Taiwanese-style mahjong. (Photo courtesy of author’s collection)

World Championships

In 1998, mahjong was finally codified on an international basis and use the simplified Chinese rules for international tournaments.

“Solo,” Online-Digital Mahjong

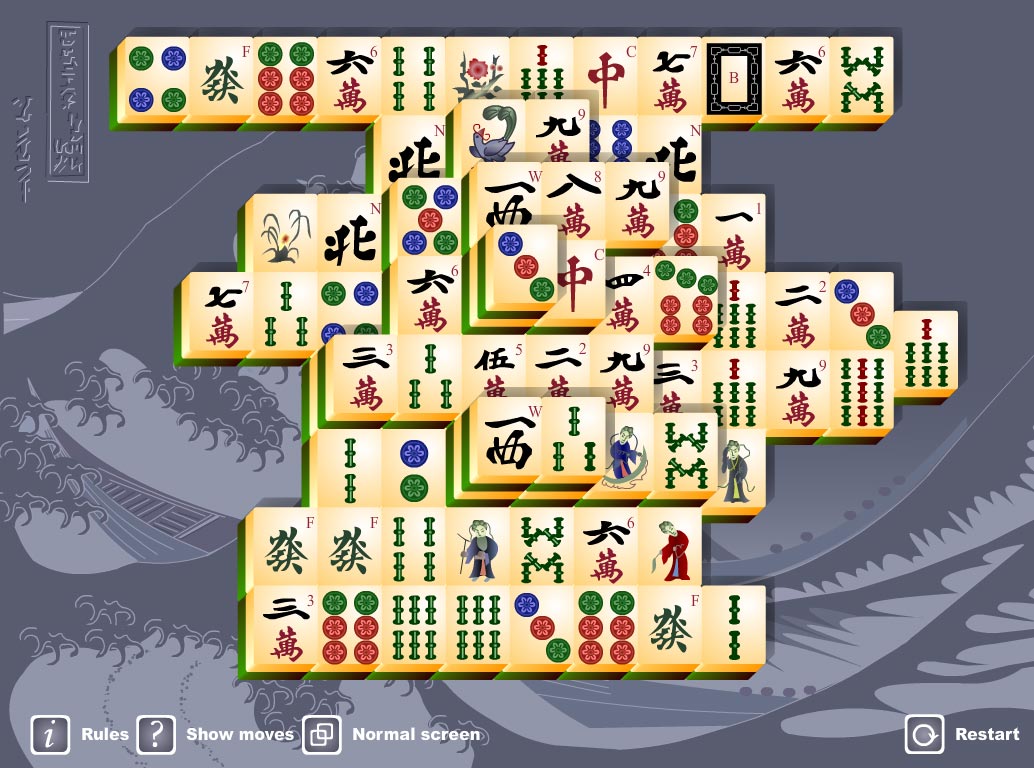

If you have the hankering to play “mahjong” but can’t find a suitable quorum, there is, of course, the Internet. There is www.freemahjong.com (screen-grab below, to see what it looks like). While it’s not quite “true” mahjong game, where you play against three other un/known opponents, this is a great site for sharpening one’s mental acuity.

The www.freemahjong.com site – an online game you can play solo (i.e., no other digital co-players are needed).

I’ve also discovered that one of the greatest benefits of playing mahjong, bridge, chess, crossword puzzles, Scrabble, or any other mind-challenging diversion, whether solo or in the company of friends, is one gets to put those little grey cells to use, as the famous detective Hercule Poirot often spouts. As proven by medical studies now, such mental challenges stave off the early onslaught of Alzheimer’s. It helps keep the dementia wolf at bay. I find that playing mahjong even digitally keeps my cognitive powers in tune.

Did they play mahjong on the Titanic? It sure looks like it here. A slight variation though--youngsters keeping cool in a Cebu pool. Can Flipper the dolphin kibitz? Do you stop when your feet get all shriveled and prune-like?

The Tale of the Ribald Aunt

One of the more, shall we say, delicious memories of my younger mahjong days with the family was the antics of one aunt (by marriage) at the table. Let’s call her Tita G (to protect the guilty), who imbued her mahjong-playing with the most ribald double entendres that would have made Mae West blush. With her language at the mahjong table, one would never have guessed that Tita G was convent-educated (a dyed-in-the-tartan Assumptionista no less and from a socially prominent Manila family). Tita G’s resumé also boasted a summer crash course at the Cordon Bleu in Paris, and she baked a mean fruit cake at Christmas time.

In Tita G’s mahjong lexicon, nearly every tile had its own sexually loaded backstory—for example, when the “two dots” tile was discarded, she exclaimed, “ayan . . . pang gabi!” (voila . . . for night-time use only!). And there were others equally hilarious. But she was really harmless, and I thought her totally endearing with her mahjong exclamations and innuendoes, which would have made even the saltiest sailor blush.

Thus, pardon me if I declare that Manila mahjong is the best because it was the first version I learned from my family and it’s what I’m good at. I especially like, and miss the atmosphere wherein the quorum injects the saltier tones of the vernacular with Spanish invectives (Coño, Puñeta, Cabron!) no less, turning the game into a really good de-stresser.

Wait – kang! (four of a kind) – Hindi, Harang! (which means one player declares a four-of-a-kind; however, another player literally “steals” the favor by taking that tile to declare his/her mahjong! No; not “Hindu/Hindi” but “No! it’s harang – or Ambushed!)

Here’s to you, Tita G. Bottoms up. And I also miss your heavily spiked Christmas fruitcake.

Sources:

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/18/arts/artsspecial/18MAH.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_playing_cards

http://www.mahjongsets.co.uk/history-mahjong.html

https://gamesandcasino.com/mahjong/games.htm

https://www.nationalmahjonggleague.org/

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Competition_Mahjong_scoring_rules

http://sillytale.com/?page_id=471

Thanks to Jean (of the San Leandro Chinese Mahjong Meetup group).

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. His newest book, “Of Adobe, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles – An Anthology of Essays on the Filipino-American Experience and Some. . .”, features the best and brightest of the articles Myles has written thus far for this publication. The book is presently available on amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, Europe, and the UK).

Myles’ two other books are: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2016); and Thirty Years Later. . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes published last year, also available from amazon.com.

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH) for whose Journal he has had two articles published; a third one on the story of the Rio 2016 cauldrons, will appear in this month’s issue -- not available on amazon.

Finally, Myles has also completed his first full-length stage play, “23 Renoirs, 12 Picassos, . . . one Domenica”, which was given its first successful fully Staged Reading by the Playwright Center of San Francisco. The play is now available for professional production, and hopefully, a world premiere on the SF Bay Area stages.

For any enquiries on the above: contact razor323@gmail.com