My Years with Marcos (Opposing Martial Law)

/This is an excerpt from Endless Journey: A Memoir by Jose T. Almonte, as told to Marites Danguilan Vitug (Cloverheads Publishing, 2015). Reprinted with Permission.

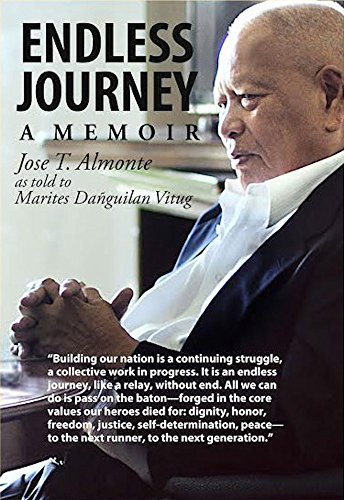

Endless Journey: A Memoir by Jose T. Almonte

Pakistan had declared martial law in 1969, so we visited it and met with Gen. Yahya Khan, the country’s chief administrator of martial law. We asked him about the experience.

We did not know that Marcos had already instructed Juan Ponce Enrile, defense secretary, to prepare the legal basis for martial law; what was to become Proclamation 1081. It was only when Enrile published his memoirs that I learned of this. Enrile wrote that Marcos asked him in early December 1969 to “study” the president’s “powers under the commander in chief provisions of the Constitution. He said that he was foreseeing an escalation of violence and disorder in the country, and he wanted to know the extent of his powers as commander in chief.” Marcos told him the study “must be done discreetly and confidentially.” Enrile wrote: “Proclamation No. 1081 of 21 September, 1972 recited fully and faithfully all the facts that President Marcos needed and used to justify the declaration of martial law in the country…I drafted and prepared the documents…used to declare martial law.”

Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor, Jr. (Source: ellentordesillas.com)

When Marcos asked Melchor to write a paper about martial law, he wanted to validate his intentions – but he didn’t get that. In our study, we said that while martial law may accelerate development, in the end the Philippines would become a political archipelago, with debilitating, factionalized politics. Our findings led to the conclusion that the nation would be destroyed because, apart from the divisiveness it would cause, martial law would offer Marcos absolute power which would corrupt absolutely. Alex believed this conclusion and advised Marcos not to declare martial law. We only had one copy of this paper and it was given to Marcos.

This explains why Alex, even if he was the executive secretary, was not part of the team – the so-called Rolex 12* – that planned the proclamation of martial law. It was Enrile who became the administrator.

Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile with confiscated firearms from the MV Karagatan (Source: The Kahimyang Project)

After Marcos announced that the country was going to be under martial rule, he asked Alex to stay in the Cabinet. Alex and I were very close. In terms of policy, I knew as much because we discussed these together.

“I know you are against martial law. But I have already declared it,” Marcos told Alex. “I want you to stay on as my executive secretary.”

That day, Alex called me and asked if I could ride with him. We drove around Manila and even reached Laguna.

“Joe, we didn’t agree with martial law,” he began.

“Sir, you know, the paper we made was theoretical. But if Marcos will really be sincere, it can be done. Look at Park Chung Hee [South Korea’s president]. But it really depends on Marcos,” I said with hope.

“If Marcos doesn’t live up to what we believe in, we will resign,” Alex firmly said.

We spoke in the car for hours.

I asked our group in UP to give martial law a try. I told them that Alex had agreed to stay on as executive secretary. I believed in the credibility of Alex because he was not part of the original group that agreed to martial law and neither was he part of the administration of martial law.

Alex asked me if the group could write the philosophy and purpose of martial law. We thought about this very seriously and devoted more hours to it than the earlier study on whether to impose martial law or not. We fleshed out Marcos’s idea of a “new society” in policy papers and books.

During the first year of martial law, it seemed that Marcos was right. Martial law worked. Discipline seemed to be in place. There was a semblance of order. People were behaving, they were queuing, as if the public was under a disciplinary spell. Marcos was serious about his infrastructure program.

President Ferdinand Marcos (Source: The Martial Law Chronicles)

Six months after martial law, surveys showed that Marcos and the military rebounded, gaining high points. But before martial law, Marcos scored very low in these surveys, as did the military and police. I came across this information because one of the things I used to do was to coordinate opinion surveys. I do not have copies of these surveys anymore but those conducted much later, in 1984, by the Philippine Social Science Center and the Bishops-Businessmen’s Conference showed similar results. Public opinion on Marcos’s performance was positive, with a score ranging from 44 to 47 percent. I remember that the numbers were much higher immediately after martial law.

Alex often brought me along when he met with Marcos during the early months of martial law. I watched the interaction between them and I could see the sincerity of the president, or Marcos must have been a good actor.

Once, he called Alex and me to a meeting and it was raining hard. Alex noticed that the ceiling in Marcos’s office was leaking. “Mr. President, maybe we should have this repaired.”

“No, no, no,” Marcos replied. “That should remind me that we are in a revolution.”

This was quite dramatic. After interacting with the president during my years in Vietnam, I continued to place him in high esteem.

More than a year after martial law, I could see, however, that this reformist sheen was giving way to the true nature of martial law. Once Marcos consolidated his political power, he did not use this to build the nation. That was the start of the deterioration of martial law because abuses began to permeate the system. Apparently, the first lady, Imelda Romualdez-Marcos, and a wealthy businessman, Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco, tightened their hold over the cronies of Marcos.

At one time, Alex was asked to prepare the speech of Marcos, a report to the nation. He identified ranking officials who were backsliding and recommended that they be purged. It so happened that a number of these were close to the first lady. President Marcos heeded Alex’s advice, and in his State of the Nation Address which he delivered at the Quirino Grandstand, he announced “the beginning of a sweeping, complete, and exhaustive reorganization of the government.” He accepted the resignations of the commissioner of customs, Rolando Geotina; of internal revenue, Misael Vera; and of land transportation, Romeo Edu; the secretary of public works, transportation and communications, David Consunji; and of public highways, Baltazar Aquino, among others.

A big problem thus ensued between Imelda and Alex, who was still backed by Marcos. This took place a few years after the Dovie Beams scandal, in which Marcos’s affair with an American B-movie actress was exposed, and from which Imelda was still reeling.

Mrs. Marcos demanded the resignation of Alex and left the Philippines – she traveled to Japan, to the US – and threatened not to return until Alex was out of the Cabinet. She alleged that Alex was involved in a plot to overthrow President Marcos and that I was his principal coup planner. Of course, there was no truth to this outlandish rumor. It appeared that the first lady distrusted Alex and me because we were obstacles to her plan to succeed Marcos.

Years later, this was confirmed when papers seized from Marcos in Honolulu, after he fled the Philippines in 1986, showed a handwritten decree dated June 7, 1975 providing for the creation of an executive committee, to be headed by Imelda. It would assume powers and responsibilities in case Marcos died or was permanently disabled.

What Marcos did was not to fire Alex but to abolish the Office of the Executive Secretary including those of his deputy executive secretary and assistant executive secretary. In a decree, he replaced these offices with presidential assistants. Alex was retained, however, as a director of the Asian Development Bank and board member of the Development Bank of the Philippines. It was during this time that I submitted the first in a series of resignations, but Marcos retained me in the PCAS [Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, located in the UP Diliman campus], despite the objections of Maj. Gen. Fabian Ver, the Chief of the Presidential Security Command, who shared Mrs. Marcos’ suspicions.

Brig. Gen. (Ret.) Jose T. Almonte’s long career in government culminated in his appointment as President Fidel V. Ramos’ national security adviser. He retired from public service in 1998.

Sidebar

The Rolex (or Omega) 12

*The Rolex (or Omega) 12 is the group of defense officials and two civilians tasked with the implementation of martial law. They were reportedly given a gold watch each:

Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile,

Philippine Constabulary chief Maj. Gen. Fidel V. Ramos,

National Intelligence Security Authority chief Maj. Gen. Fabian Ver,

Lt. Col. Eduardo "Danding" Cojuangco, Jr.

Army chief Maj. Gen. Rafael Zagala,

Constabulary vice-chief Brig Gen. Tomas Diaz,

Armed Forces Chief of Staff Gen. Romeo Espino,

Air Force chief Maj. Gen. Jose Rancudo,

Navy chief Rear Admiral Hilario Ruiz,

ISAFP chief Brig. Gen. Ignacio Paz,

Metrocom chief Brig Gen. Alfredo Montoya, and

Rizal province Constabulary head Col. Romeo Gatan.

For more of this story:

https://news.abs-cbn.com/focus/04/12/13/omega-12-behind-marcos-martial-law-us-envoy