My Pioneering Grandfather

/Wedding picture of Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara and Esther Lheritier Tempongko, 1925

He was born a Spanish subject on January 4, 1894, the son of Sisenando Alcantara and Cipriana Ceasico. The Alcantara family was of modest means and descended from Chinese migrants who had adopted the name, most probably from a Fil-Hispanic patron. The name “Ceasico” also indicates Chinese roots. These Filipino peasant and Sinic migrant origins might explain their capacity for hard work (Lolo Sisenando or Tado was said to have been a cemetery caretaker while Lola Cipriana took in wash to supplement the family income), as well as a respect for scholarly achievement. The Alcantara couple was to raise their four children, Vivencio, Inocentes, Francisco and Dolores, as students of Medicine, Law and Education. They were humble but ambitious for their children.

The American interim saw the explosion of both private and public academic institutions and the spread of English. In Spanish times, it was generally the elite with their mastery of Spanish and their wealth who went on to higher education in institutions like the University of Santo Tomas. The Philippine Revolution of 1896-98 manifested the desire of the Filipino people for a more equal access to opportunity and wealth as well as a break from an authoritarian past.

My grandfather Lolo Viving and his siblings were products of these times. He was baptized in his parents’ chosen church, the Philippine Independent Church (also known as the Aglipayan sect) and learned English from a Thomasite teacher (American teachers came on board the ship Thomas). He thus spoke an accent-free English (while also being a speaker of Spanish, Tagalog, Ilonggo, and his local dialect Kinaray-a). He entered public school in Iloilo City, enabling him to later enter the University of the Philippines(U.P.) Medical School in Manila. Though he was not the class valedictorian, he would top the Medical Board exam.

U.P. played a major role in his life. The Philippine General Hospital was where he practiced and established the first Broncho-Esophagology Clinic in the Philippines. U.P. was also where his future wife, Esther Tempongko, earned her Associate of Arts degree. He had tutored her in English prior to her enrollment there, although with her ear for languages and flair for writing, she was probably just as linguistically savvy.

In Lolo Viving’s time, Eye-Ear-Nose-and-Throat (EENT) were still associated disciplines and so, Dr. Alcantara would practice medicine as an EENT specialist alongside Dr. Aristeo Ubaldo, the nephew of Dr. Jose Rizal. Famously, Dr. Rizal had been an eye specialist and had successfully operated on his own mother, Teodora Alonzo-Rizal, to remove her cataracts.

One still-surviving patient of my grandfather, a Tempongko relative, Aida Mercado-Adia (now a ripe and healthy 100 years old), remembers him operating on her ear infection. Her memories of him as an avuncular and dedicated doctor were echoed by an earlier reminiscence of his student at PGH, the late Dr. Anacleta Villacorta-Agoncillo (widow of historian Teodoro A. Agoncillo).

Married in 1925 and with one child (my mother, Erlinda, born in 1926) and another on the way, grandfather Vivencio was selected in 1927 to further his specialization as a pensionado (or government scholar) at Temple University in Philadelphia under the renowned Chevalier Quixote Jackson.

Chevalier Jackson is considered a pioneer in the modern method of tracheotomy as well as in developing methods, techniques, and inventions for the recovery of foreign bodies lodged in the bronchi and esophagi of children and adults. This specialization would be known as Broncho-Esophagology, and valuable knowledge imparted by Dr. Jackson would be used by Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara in establishing the first Broncho-Esophagology Clinic at the University of the Philippines in 1932.

For those unacquainted with such an esoteric discipline, it may seem something best left for specialists. But parents of children in life-threatening situations involving accidentally swallowed safety pins and tiny toys know how crucial the work of doctors in this field can be.

The polymath Chevalier Jackson was also the author of several outstanding books, including his autobiography and technical tomes on his discipline. The Life of Chevalier Jackson became a bestseller and missed becoming the Book of the Month Club winner to Marjorie Kinnan Rawling’s The Yearling in 1938. His scholarship manifested not only a keen mind, but also an interest in many diverse aspects of knowledge and society. I wonder whether Dr. Jackson, while teaching an Asian doctor at Temple University, might also have infected him with that spirit of curiosity and culture.

Or it may have been part of his original makeup. On his way home from the United States in 1928, Vivencio Alcantara indulged himself in what must have been a lifetime dream, traveling to Europe. It appears that the city that impressed him most was Vienna, a medical center and home of Dr. Sigmund Freud. Austria also engendered the classical music, love for which he transmitted to his children. We were hummed to sleep with the Blue Danube, the Merry Widow Waltz and Die Fledermaus. My grandmother often said that doctors then were like Renaissance men, taking interest in cultural matters beyond their profession and training. Lolo Viving certainly had a hand in seeing to it that his daughters trained in ballet and piano and would be voracious readers.

Having studied Humanities myself and specialized at the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna, I appreciated this aspect of my grandfather all the more.

In second row far right, Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara and wife Esther celebrate Christmas with Tempongko clan, 1940

The years 1935 to 1941 were among the Philippines’ most promising since these coincided with the Philippine Commonwealth, when the country was transitioning towards full independence. Pictures of my grandparents, Vicencio and Esther Alcantara, show them celebrating Christmas around 1940. Dressed in a white sharkskin suit, Dr. Alcantara shows his prosperity in his bearing and corpulence. The dreadful war years of 1941 to 1945 were still to follow.

The Bronco-Esophagology Clinic was proof-positive of the medical progress of the Philippines, which closely followed trends in the United States.

Like Chevalier Jackson, Dr. Alcantara liked to collect anecdotes and keep the odd item painstakingly fished out of children’s gullets. He prided himself on being able to sew neat stitches, which were required in his delicate work.

My mother recounted that he kept as souvenir the only peso that a grateful mother had and had given to him as a token payment. Money was never a factor in accepting patients, some of whom in those days could only pay in chickens or centavos, graciously received to indicate appreciation.

Dr. Vivencio Alcantara passed away during the bombing of Manila on February 21, 1945. He had suffered an earlier stroke during the Japanese occupation and the obvious strain of evading bombs while seeking shelter in the northern shore of Manila must have been trying for him and his family. Together with other Tempongkos, his wife and daughters had to load their father and bare essentials in wooden carts and push to safer ground beyond the Nagtahan bridge. Finally, unable to speak due to his stroke, he communicated in sign language his wish for a priest to attend him.

He was given temporary burial on the grounds of the San Lazaro Hospital, and Esther Alcantara had to beg someone for clothes to bury him in, an irony for someone who had prized elegance during his lifetime. I finally know him only through the inscription on his tomb at the North Cemetery.

Still, his legacy lives on.

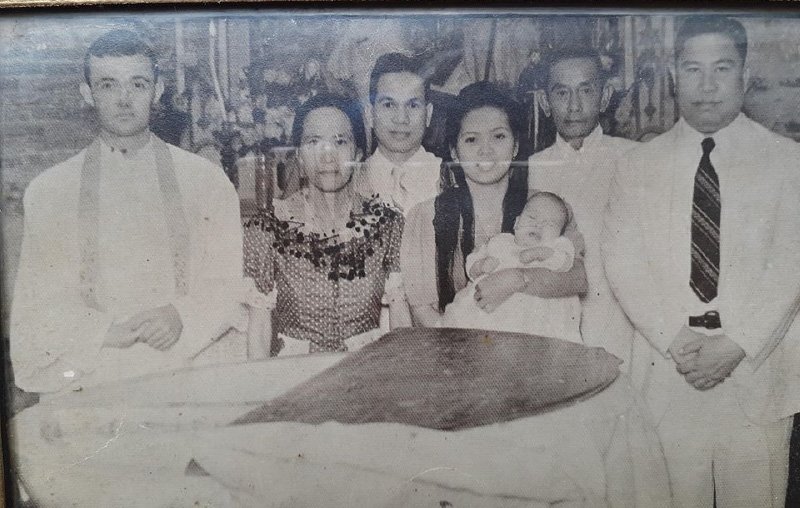

Far right, Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara at baptism of his godson Cezar, son of his widowed sister Dolores Lopez(second from left). Their father Sisenando Alcantara is second from right.

His godson, Cezar Lopez (son of his sister, Dolores, and her husband, Simeon Lopez, who was killed in the Bataan Death March) would become a doctor, as did Cezar’s daughter, Aurora, an EENT specialist like her father. Two great granddaughters, Olivia Reyes and Aimee Calejesan-Maslach, would also follow in his footsteps. My mother, Erlinda Alcantara-Reyes, had also dreamed of becoming a doctor but concentrated instead on raising a family of five and becoming a Speech teacher.

The U.P. College of Medicine has honored Dr. Vivencio Alcantara in a series of lectures named after him and cited him as having established the first Broncho-Esophagology Clinic in the country. Having lasted for barely a century, Dr. Vivencio C. Alcantara’s life gives us a glimpse into our country’s history and its many twists and turns.

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He is now engaged in writing, traveling, and is dedicated to cultural heritage projects

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.