My Father’s Fruit Salad

/Fruit Salad (Source: Panlasang Pinoy)

Filipino Fruit Salad

Prep Time: 20 minutes

Yield: 30 servings

Ingredients

6 14.5 ounce cans Del Monte fruit cocktail

½ rectangle Philadelphia cream cheese

½ 14 ounce can sweetened condensed milk

1 Red Delicious apple

¼ container Cool Whip whipped topping

Directions

Strain fruit cocktail until dry.

In large container, mix softened cream cheese and condensed milk.

Peel and cube apple. Add all fruit to cream cheese mixture.

Combine thoroughly with spoon. Fold in Cool Whip.

Transfer to serving dish, cover, and chill overnight.

My father moves around the kitchen, tsinelas (slippers) slapping against tile as he gathers the ingredients for Filipino fruit salad onto the counter. He begins as he always does.

“It’s so easy to make, Jen. Very easy. So simple.” His preface before each cooking lesson begins the same way, whether he’s preparing cassava, pancit, or pinakbet (mixed vegetable). He says this, I think, because he knows that I will only try if it is easy.

Growing up, my contributions to our family dinners had been the simplest—to cook rice and set the table. Born and raised in the U.S., I’m all take-out restaurants and drive up menus. I am pancake cheeseburgers and single-serving ketchup packets. I am a hesitant cook, easily intimidated by complex directions and unfamiliar ingredients. But today, the lesson is Filipino fruit salad, our version of ambrosia. Even I cannot mess up canned fruit cocktail and Cool Whip.

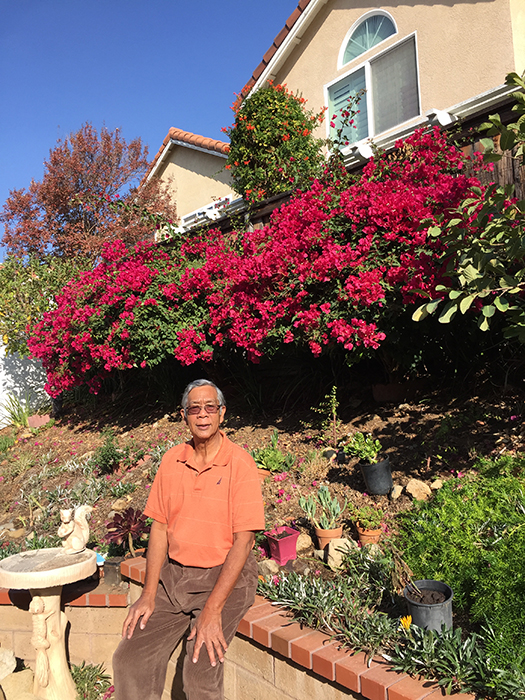

Inocentes Palmares Jr. (Photo courtesy of Jen Palmares-Meadows)

“Try. Just try. You’ll see how easy it is. How delicious.” He says this again and again, emptying can after can of fruit cocktail into a colander, draining juice into the sink. “Try. You will make it and your children will like it.”

Beneath his fervent encouragement, I understand a certain urgency, and make a silent promise to catalogue his ministrations. I survey his ingredients. Cream cheese. Condensed milk. Cool Whip.

“Dad, where did you learn to make this? Not back home?”

My father grew up in the Philippines, in a modest wooden home built by his father after the war. Their diet of salted meat, fish, fruits, vegetables and rice, included ginger tea and evaporated milk—rarely cream.

“Oh, when your mom and I moved to the States and went to parties, people made this. We saw how much everyone liked it, how simple it was.” He cuts a softened rectangle of cream cheese in two and places half into a large Tupperware container where he will combine everything.

Mr. Palmares saying a blessing over our family during a gathering (Photo courtesy of Jen Palmares-Meadows)

I imagine my young immigrant parents, newly arrived to the land of milk and honey, attending gatherings and making friends. They would have wanted to offer a dish both delicious and affordable.

He pops two holes into a can of condensed milk and holds it over the cream cheese, all patience as the yellowish goop dribbles out. With the back of a spoon, he mashes the chunks of cream cheese into the condensed milk, stirring them together.

He murmurs beneath his breath as he stirs, drifting into a sing-song. Those who know my father well are accustomed to the sound and music that often escapes him, sometimes in the form of a song, a whistle, a series of clicks, or a repetitive chant. When I was I child, I would sit on the stairs listening to him read his books aloud at our dining room table, his slow, deep voice reverberating against the walls, the words settling inside me like a tonic. To this day, when revising my own writing, I must read everything aloud, paying careful attention to pauses and rhythms.

The Palmares family at Thanksgiving (Photo courtesy of Jen Palmares-Meadows)

My father likes to host parties, to gather family. He grew up the youngest of 12 children. I try hard to imagine them sharing one table, brown legs of various lengths swinging from benches and chairs. “All the children ate first, then the older ones,” he tells me. “We ate a lot of stews. A lot of stews.”

With five offspring of his own, his brood is large enough, plus the addition of their spouses and children, an intimate gathering of our immediate family alone can be raucous. Perhaps this is why he is always surrounded by song—he is unaccustomed to silence.

“Make sure the fruit is dry before you add it—no juice, otherwise it will be runny.”

The fruit plops into the mix—mushy yellows and reds, diced peaches, pears, grapes, pineapple chunks and cherries. The cherries are so elusive. There’s never enough.

He peels an apple, chops it up, and adds it to the bowl.

“You add the apple so you have something fresh.”

“Finally, he pours everything into a crystal ice bucket for presentation, a fancy symbol of the high regard to which we hold my father’s fruit salad.”

I don’t tell him this, but the apple is my least favorite part. I always eat the apple chunks first so I can enjoy the rest without their inclusion. Every family makes the dish differently. Some use mango or jackfruit. Some add jarred macapuno or nata de coco. We do not. When eating someone else’s fruit salad at a party, I separate the worm-shaped coconut shreds and cubed jelly to the side of my plate. Filipinos have interesting dessert combinations that my Americanized palette still finds peculiar—corn and cheese ice cream, tapioca and bean iced drinks. Filipino experimentation in dessert is a testament to our ingenuity, adaptability, our willingness to make the best of what we are given.

One hand gripping the bowl, his other arm raised, elbow pointing up, he combines the fruit with the creamy mixture. He is completely absorbed in his task, his head bowed. Each time he pulls the spoon free, the cream creates a satisfying suction sound as if the dessert is trying to swallow the spoon. The sound of wet cream is, I know, a rich one.

Reaching into the refrigerator, Dad pulls out the Cool Whip. He adds a heaping spoonful and folds in the whipped topping.

“Just a little bit, Jen. To prevent it from getting yellow. When you add the whipped cream, it’s like icing on the cake.”

I think I hear satisfaction in his humming when finally, he pours everything into a crystal ice bucket for presentation, a fancy symbol of the high regard to which we hold my father’s fruit salad. His hands make quick work of stretching plastic wrap over the top and sliding it into the already full refrigerator to allow the cream cheese and condensed milk to thicken.

Because my mother likes to worry, no matter how many dishes we prepare, or how many dishes guests are likely to bring, she will order more. She and my dad will leave a few hours before the party and return with catered lechon and lumpia, and if we expect lots of guests, with folding tables and stacking chairs that we will set up in the backyard.

The minutes before the guests arrive are a frenzied putting away of things. Each time the front door opens, a new myriad of voices join the cacophony. depending on how long life has kept me away from home, it has been a year, sometimes more since I have heard these voices. We embrace, pressing our cheeks. They tuck their purses behind the sofa, and under chairs. And by the door, so many shoes, on shoes, on shoes. And the television playing the Lakers game, or the boxing match, is on high, and gets turned up higher still, because the voices are so loud, but it is good.

At last, it is time to line up. We circle about the table, shuffling at first and then moving with more certainty, our brown arms reaching over steaming platters of rice, mechado (beef stew) and pancit malabon. We exclaim over the leche flan and lechon. We will need seconds and then thirds. We circle the table again and again, dancing before the feast, our bent heads sometimes sending the chandelier swinging.

Later, I won’t bother with a dessert plate, but spoon the chilled fruit salad onto my already used plate, atop straggling grains of rice and savory sauces. These leftovers are the final ingredients, a bit of heart from each dish I have consumed, a gift from every member who has participated in this feast, every person my mother and father have gathered to our table. Settled on the couch, alongside siblings and cousins, I attempt to capture every conversation, every flavor, ever cognizant that time changes all things. My comfort is the spoon moving through my father’s fruit salad, and the familiar texture of congealed cream cheese and condensed milk.

This essay was first published in Redivider.

Jen Palmares Meadows writes from the Sacramento Valley. Her essays have appeared in The Rumpus, Fourth Genre, Brevity, Denver Quarterly, Hobart, The Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere. She has a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from California State University Sacramento and is currently completing a hybrid collection of essays.