Martial Law Stories: Remembering

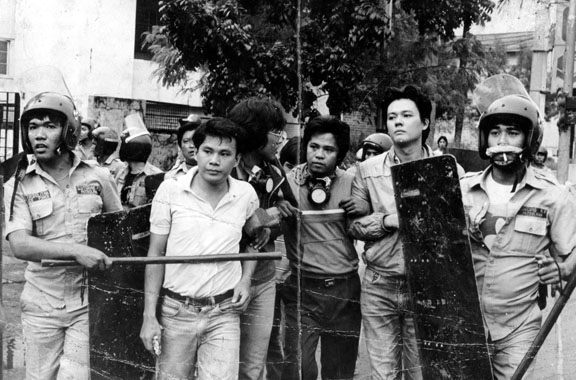

/The Martial Law years (Source: retrospect.ph)

My friend Tony Tagamolila was the Collegian editor-in-chief. I no longer recall any of the feisty editorials he wrote and I cannot tell you what moves he made at the Diliman campus to make him a legend there, but Tony got himself elected president of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines (CEGP), an org counting 150 publications across the country’s three main islands. One hundred fifty. And I remember that that election—in the summer of ’71, at UP Los Baños—became downright scary, because it would determine the fate of all campus papers at a very political time. Who would rule? The editors who liked being in the good graces of Malacañang or the editors who couldn’t care less? Tony was with the latter, of course.

Tony Tagamolila (Photo courtesy of Didi Manarang)

It became one really scary election. I was 20, and I had never witnessed anything like it up close. One editor voting for Tony was Manolet Dayrit, of the Ateneo Guidon, and one day the fellow was jogging in Los Baños, alone, when men suddenly materialized and chased him uphill and downhill until he crashed into the dorm, totally wrung. Goons, he reported. Lucky thing Manolet was a fast runner, or he might not be around today to be dean of the Ateneo de Manila University School of Medicine and Public Health. In the end, CEGP’s leadership was seized by the camp that couldn’t care less, and so the CEGP fell pell-mell under the government watch list.

I remember the irony and contrast. The guy to lead the hot org, Tony, was a short and wiry Visayan guy who was so cool and charming, he was always getting into girlfriend trouble. Girls were always hovering around him, so his girlfriend started hovering around him too, until colleagues had to tell him to please tone down the charm so we could get real work done. There was a lot to do! In the provinces, campus editors were being scared witless with threats of expulsion, or worse. In Manila, campus papers were being threatened with decimation. All a school had to do—and some colleges did this—was pull out the school-paper fee from the overall tuition fee and, voila, no more school paper. Problems, pressure, politics mounting all the time. Naturally, our band of editors helped each other out. We wrote pooled editorials, produced special editions using the CEGP logo, issued manifestos and petitions, and marched under the banner of freedom of speech. We even organized forums like this one.

The year was ‘71. The writ of habeas corpus had been suspended. This meant you could be tried and sentenced for a crime without you ever being brought before a judge. Activists saw this as creeping militarization in play. True enough, the very next year, ‘72, martial law fell hard on the country.

I saw Tony only twice after that. We had scattered. On our heads were an Arrest Search and Seizure Order (ASSO) signed by Defense Minister Johnny Enrile—yes, the same 94-year-old running today for a seat with a six-year-term, which makes him 100 years old when his term ends—and Tony and I, to escape arrest, joined the Underground, but landed different work assignments.

Clandestine was the word. We communicated in quiet, through letters sent in secret, written in code, on innocuous cigarette paper, in the tiniest folds, to be hid thoughtfully in the lining of the sole of a shoe.

That first time, we met in España, near the railroad tracks, at his mother-in-law’s grocery store, which he was now managing. He could not get a job in the few publications allowed to operate. His name being prominent—he also had a famous soldier-brother who joined the rebels—he would’ve been arrested on his first day. So there I found him, doing the grocery inventory on rolls of toilet paper and boxes of tissue, and his manner was the same as when he was president of 150 campus papers: calm, inscrutable, soft-spoken, engaged.

As I left him, I felt strange. I thought of him, and many intellectuals like him, now scattered everywhere, making do with anonymous jobs that were honest and necessary but none of which tapped an iota of their skills and gifts.

The next time we met, I felt even stranger. We were in a tiny apartment off West Avenue. Four of us, friends who had become attached to each other after living together at CEGP headquarters several days a week for many months. Tony and Babes Calixto were leaving for the countryside, to do political organizing. Two of us wanted to say proper goodbyes. We talked through the night—about family, preparations, the land trip, baon. We did not talk about danger or risk. We stopped only when sleep overtook us on the long banig under the low-hanging kulambo. Then my memory blurs. I don’t know now if we hugged. We might have thought it too bourgeois. I would never see them again.

Leopoldo Calixto, Jr. (Source: Bantayog ng mga Bayani)

In ‘74, while I was in prison, news came to me that Tony and Babes were dead. Tony in Aklan, Babes in Iloilo, two days apart on the month of February. Today their names are engraved in the Wall of Remembering at Bantayog ng mga Bayani, but, many times, when I see their names there, all I see is us talking about our lives on the banig under the low-lying kulambo.

The Underground was not about hiding and waiting for a dictator to die; it was about bringing down a dictator and working very hard to make it happen. The Underground was also a complex network of allies, organizers, artists, cultural workers, donors, lawyers, nuns, and writers. Writers joining the Underground all produced something—literary, historical, journalistic. I found myself doing journalism with a very small group: a teacher/organizer; an artist/photo journalist; an ex-Collegian editor/mechanical engineer; and a veteran journalist/poet/translator.

Every day it was just the five of us living together in apartments we abandoned constantly, to stay a step ahead of the enemy. Over 15 months, we moved five times. We had left our families, it was safer for everyone that way. And to relieve them from the burden of knowing but having to act like they did not, we could not tell them where we were.

When I think about it now, my parents must have done a lot of praying. Soldiers had already knocked on our house, presented the ASSO signed by the minister, and rifled through my clothes, books, drawers, on a night I happened to sleep in the home of a workmate I was recruiting to become part of our support group. Mama and Papa must have done the nightly rosary for their eldest child who could be anywhere, living among strangers. They need not have worried really. I was never among strangers. I had found myself a family.

We took care of each other. At the very least we tried to be sensitive, no one went around shouting. Well, except that one time when the teacher/organizer, the oldest among us, picked a loud fight with me for no reason. Turned out his blood sugar was high and he hadn’t eaten, and when someone quickly cooked him an egg, he was as good as new. Except for that one time, we were really always polite with each other.

I remember it was my turn to go to market to buy our precious bangus, the only thing our budget could get us. Our UG house was in Novaliches, so I was off to Cloverleaf. What I did not tell anyone was that, at 22, I had never been alone in a marketplace. I did not know the first thing. Keeping brave, I tried to remember the chatter of the guys. They had said something about fish having “pulang hasang” when it was fresh. Eureka! So I looked hard for red gills, picking every bangus that was red. When I got back, I found out the fish were nearly almost all spoiled! The men didn’t say much, but I caught on because they all converged in the kitchen, washing and cleaning all the fish right away, salting them, soaking them in vinegar, and just doing things to them. Turns out, they were saving the week’s supply of bangus from the trash bin. I had thought that red gills meant red eyes because the gills were so close to the eyes! So I had bought every red-eyed bangus in Cloverleaf. I noticed they just never again sent me to the market after that. But, I was good at cleaning house, so I did a lot of that.

We may have been nice and polite, but we did not live like the bourgeoisie, with their endless prattle about life’s essential meaning over nice prolonged lunches. We had no time. There was always something to read and write. Our kind of prattle had to do with grammar and styling issues, with strict journalistic rules on sourcing data and fact-checking, not to forget the all-important proofreading. We were proud of our Taliba ng Bayan, even done in primitive stencil, and our paper would go down in protest history as the first Underground paper to appear under martial law. Martial law was September 21, 1972; the first issue I could retrieve of Taliba ng Bayan was dated November 30, 1972.

Before her arrest, the author was one of the writers of "Taliba ng Bayan," an underground newspaper during martial law. (Source: http://iraia.net “Pathless Travels” by Pio Verzola Jr.)

Of course, this was no light reading. Anyone caught with the paper in his hands faced quick arrest and detention, if not torture; anyone caught producing the paper faced even worse. Indeed, Obet Verzola, our ex-Collegian editor/mechanical engineer, and Pete Lacaba, our journalist/poet/translator, go down as two of the most heavily tortured writers in Camp Crame.

(Pete, an Ateneo college scholar by the way, finally got out of prison—he had contracted tuberculosis there—because Nick Joaquin, whom the Marcoses wanted to name National Artist, said he would only accept the award if Jose F. Lacaba, his fellow journalist at the Free Press and Asia Philippines Leader, be released first.)

I must admit, these many decades after, I don’t think I made a huge contribution to Taliba as writer. It was in Tagalog, and Tagalog news reporting had its own flavor. For instance, Tagalog sentences tended to start with verbs. Like: Inalmahan ng mga estudyante… Kinondena ng taong bayan…Inusisa ng opisyal… I was an English comparative lit major. In grade school we were fined if we spoke in Tagalog. I remember Pete forever rewriting me—and most everyone in the group—until, one day, our guy with the high sugar told him, “Pareng Nes, pakitira mo na naman ang period.” It became everyone’s throwaway sentence: “Pakitira naman ang tuldok ko.” Can you leave the period intact, please? (Nes/Nestor was Pete’s UG name.)

The law finally caught up with me, as it were. I was 23. Our group—which included now National Artist Bienvenido Lumbera and today’s best-known screenwriter, Ricky Lee—was incommunicado for eight days, when our interrogations were conducted. After Aguinaldo, the arresting team sent us to Ipil Detention Center in Fort Bonifacio, a prison camp that happened to be where Marcos sent visitors from Amnesty International when he wanted to parade his so-called benign martial law. Being once a military training camp, Ipil did have a view of blue skies above the barbed wires and sentry towers. That was a big thing; Crame and Aguinaldo could drive you insane with their unrelenting concrete.

The author's UG group held a reunion on March 19, 2019 on the occasion of Ricky Lee's birthday. Left to right: Flor Caagusan, Diego Maranan (the son of former detainees Aida Santos and Ed Maranan, representing his parents), Cesar Carlos, Jo-Ann Maglipon, Ricky Lee. Seated: National Artist Bienvenido Lumbera.

The things I remember of that time aren’t the stuff of fire and brimstone. Instead, what I remember is Rolando Tinio, who I had come under at the Ateneo-Maryknoll Drama Guild, arriving on a Sunday with his wife Ella Luansing, to visit their good friend Bien Lumbera. I was invited to partake of the repast. It really feels like I have to use repast. See, this theatrical couple brought lunch in a lovely picnic basket. Under a little thatch roof held up by four sticks, in the middle of a jogging path in that prison, right on top of the dusty earth, they spread their red-and-white tablecloth, on which they laid out pewters and silverware and fine glasses and nice breads. It felt almost English.

All told, I did not do any real writing in prison. I suppose I was living too much in the moment to capture it? Every moment there was a moment of anxiety and alertness. We had no water when there was a big fire in Makati because then the Makati Fire Department could not bring us any, so we had to quickly ration our water, giving priority to kitchen and toilet. We needed to talk our families into bringing us cans and cans of powdered milk because we had a pregnant detainee whose relatives from the province could not visit. We had our rotating chow-group duties. Chow groups were what we called the groupings we created. We had to organize ourselves well. We had to keep our environment clean—toilets clogged up and there were bedbugs. We needed to put order to our days. And, in between those hours of chow duty, we planned The Great Escape. Escape was, to a political detainee, the primary goal. And after many months, one very rainy night we managed to get three females and three males to escape. They walked up and down the slopes of Fort Bonifacio, military cars whizzing past them, until they got to Guadalupe and into a taxi. No shots rang out that night; no one died. (One of them became DSWD Secretary for a period, Judy Taguiwalo. Another one is Lorena Barros, poet, anthropologist, and woman warrior, whose name is in the Wall of Remembering.) But, in the next several days, we were interrogated and our quarters raided. A long story.

The point being, I never wrote about any of this. I think I was just too weighed down with everyday life. I had also become rusty. My prisoner-best friend, Flor Caagusan, tells me that my first-ever published piece after prison was, for her and Ricky Lee, just “incoherent.” Heavens. I, an English major, had become incoherent! I should sue the government!

“We communicated in quiet, through letters sent in secret, written in code, on innocuous cigarette paper, in the tiniest folds, to be hid thoughtfully in the lining of the sole of a shoe. ”

Over time, I have come to live, almost lightly, with my memories. Lightly, because I can now summon them back in small doses. Lightly, because I may never again have optimism otherwise. Martial law was an ugly time. It was so, in the years before its declaration in ’72, and it was so in the years after its lifting in ’81. Marcos legitimized greed, cheapened life, held hostage an entire Constitution, disrespected even traditions. He was not a beautiful man.

Protest came alive, that was true. The just and the good had their moments of triumph, yes. But, if you must remember anything about martial law, remember this: It was not a picnic. It was not romantic. Handsome rebels like Che Guevara did not appear. You did not burst into heartbreaking songs like in Les Miz.

It was life and death. Just life and death. The loss of friends so harrowing, you cried and no sound would come out. Caloy Tayag, deacon and writer, gone missing; Jessica Sales, campus editor, gone missing. They were never found. Caloy’s mother died saying her one regret was that she had not buried her son. I stopped praying for a long while. I got angry for a long time. I had seen things my Catholic college across the creek never prepared me for.

To remember it all… to keep every big death in my head—of an Atenean in his twenties made to dig a hole in the ground by soldiers, who then made that hole his own grave; to keep every story of torture in my consciousness—of my Taliba ng Bayan colleague Obet Verzola getting his head pushed into a toilet bowl in Camp Crame… to remember it all, whole, can only leave me feeling perennially punished and forever melancholy.

I guess that is why I choose to remember what I remember. Everything is still in my head. Even the biggies: the big tragedies, the big blow-ups, the big errors. But after these are captured in books and videos, I leave them to stay there. What I allow to play in my mind are the small things: the funny mishaps, the naiveté, the bungling, the coincidences, the precious moments we were family.

After prison, returning to mainstream media was neither easy nor genial. Marcos knew the value of writers. That is why his No. 1 Letter of Instruction had to do with closing down newspapers, magazines, tabloids, even campus publications.

“The Underground was not about hiding and waiting for a dictator to die; it was about bringing down a dictator and working very hard to make it happen.”

So, I taught myself not to report news but to tell stories. No getting into the picture. No revealing outright whose side you were on. No spelling out how the reader should feel. Leaving characters and conflicts to reveal themselves through quotes, color, texture, tone, geography, description. Write poor without saying poor. Write massacre without saying massacre. The words had to fall, but with a soft thud.

We only had four major newspapers, all of them owned by cronies. Editors held on to their jobs. Hiring an ex-detainee even as a freelance contributor was, to them, a mite risky. So they gave you the runaround. They were polite, they let you talk about your article, but they did not publish. I tried hard to understand where they were coming from. I suppose they told themselves that, in rejecting my story about a village that soldiers had set fire to, they retained their positions as editors and were then around to publish the other stories that would come. Yes, why lose everything for one piece about villagers where no one was famous?

Those times, I felt pretty much alone. I was a freelance writer and in the bottom of the totem pole. To an editor, I was dispensable. What hurt was not just the rejection (not an easy thing on any day), what hurt was the thought that so many journalists, years into martial law—when watchdogs were getting lazy, when civil libertarians were getting bolder, when there was now a bit of breathing room—so many journalists still had not found their courage. When the country needed to know, it was devastating to see courage still in such short supply. And yet, I looked to their courage to keep what little I had. To think I was alone would weaken me.

It was not an inspired time. Most reporters were just grateful to have jobs. They could live with the censorship, shrug it off as a bite of reality. And then there were the other workers: machinists, typesetters, proofreaders, drivers, HR personnel, technicians. They were all just grateful the presses were open. They had families to feed.

But, slowly, gumption returned.

Sometimes it manifested itself in an individual.

Certainly, it manifested itself in Antonio Nieva. Not just once, unknown creatures stoned his apartment. His house phone rang at odd hours, and when his wife picked up, a stranger would ask where her husband was. One day, as Tony was walking along Mabini, his palm was slashed. Whoever it was didn’t want his wallet, whoever it was simply wanted to send the message that he could be got to.

None of this stopped the man. Armed with his thick glasses, his cigarettes, his beer, he bulldozed his way into organizing the union at the Manila Bulletin where workers, for the first time in memory, received the benefits due them; and he put together a bold brotherhood of unions among the biggest newspapers! So incensed were the big publishers, led by his own, he ended up being thrown out of the paper and thrown in jail.

I think to myself, How did Tony stay a union man? How did he remain so tenacious? What assurances did he give his wife? They had six children—all needed good schools, all needed to eat right, all needed to remain stimulated. Where would the money come from? The fellow could just have played to his strengths. He was, in the newspaper community, respected as a top-class journalist—he could close the front page, finish full editorials, dash off headlines, spot the weakness in a story, investigate, and write his own. Why, he could put the whole paper to bed if he had to! He was even elected president of the National Press Club at a time when the club meant something. He could have thrived just being what he was: top class. But, no, he had to go be a union man in a country that shoots union men.

Maybe, nobody thinks this is anything much. He wasn’t shot like Ninoy. He died a natural death. But I say, his is just the kind of life that makes or breaks. Try picturing Tony Nieva: a man hounded every waking day into dropping his convictions, into going for the big bucks, into staying with the accolades. It could drive a lesser person mad. It made Tony a hero.

Sometimes, gumption showed up in groups.

Here I must speak of my women friends. What a bull-headed bunch. Nearly all alphas, it was a wonder we got organized. But we did, in ’81, to help each other out of our rustiness. We wanted to get back to the writing. We wanted to do the one thing that gave us joy. We actually counted 50 of us coming together! But, within two short years, our grand plans for writing workshops were derailed. Ninoy Aquino was assassinated. And, just like that, the WOMEN—Women Writers in Media Now—became busy with expressing a people’s anger, as much as its own.

Doing what gives you joy can, of course, get you into trouble. Officially, there was no more martial law but, believe us, it was there. Our toughest encounters with government, our grittiest coverage, the waves of reportage that pushed the fight of free speech forward—these are all found in the book PRESS FREEDOM UNDER SIEGE Reportage That Challenged the Marcos Dictatorship, edited by Ceres Doyo, released only recently.

What is left for me to tell you are the small details, the personal stuff. That, for instance, I quaked in my high heels but I never let on. The night before I was to appear before the National Intelligence Board, to be interrogated about my articles on the Atas of Paquibato, I literally spent all night running to the bathroom. But, after quaking in private, and saying to the ceiling, “Oh God, if there is a God, help me!”—I appeared, composed, face unreadable but not hostile, voice at even pitch, before 13 intelligence officers, with my only ally, the trial lawyer—bless him—Dean Antonio Coronel. It turned out the dean was all I needed. He had a way of making me, not just calm, but confident. His one admonition was, “Do not answer questions about your incarceration or anything related to your politics. Stick to your journalism.” I said, “But I don’t mind, Dean, I can answer those.” And he said, “Yes, but we don’t know what they have,” moving his eye in the direction of the folders in front of each of the 13 officers. I had not given a thought to the folders; I just saw them as props. So I said, “What happens if they ask?” And Dean said, very self-assured, “I will remind them of the parameters of their invitation. And even before we begin, I will remind them of the wording of their invitation.”

It really helped that we journalists had lawyers to watch our backs—pro bono, for free! They were forever bailing us out of trouble, but I must say we did our bit for them, too. When three top lawyers in Davao were incarcerated because they kept taking on the cases of farmers, students, and sundry “subversives,” I was there, and I wrote about them in a national publication, to keep people aware they were alive and should stay alive.

A special mention must be made of Joker Arroyo—former senator, former executive secretary of President Cory Aquino, former pro bono lawyer for citizens persecuted by Marcos. It was he, with the MABINI and FLAG lawyers, who took charge of our petition to the Supreme Court to get General Fabian Ver and his National Intelligence Board off our backs. Stop interrogating journalists!

But more than the brilliance of the petition’s arguments, what we remember of Joker is what writer & NGO worker Rochit Tañedo recalls. “There was a JAJA [Justice for Aquino, Justice for All] presscon, 4p.m., in Makati, the usual ATOM and Butch Aquino crowd post-assasination,” Rochit tells in a quick text message. “Then Joker, in neat crispy barong, arrived with a three-year-old boy clinging to him. I asked: ‘Hu dat?’, and he said: ‘I came from a hearing of Jude Pardalis [disappeared in broad daylight in Marikina] and the mother asked me if I could be with him first as she had errands to do.’ So as simple as that, pro bono lawyer na, yaya pa, thinks nothing of bringing a toddler to a presscon. Naku, the boy was so hyper and kept turning around, would not eat, but would not let go of his thigh. Ganun.”

Rochit goes on, “Alam mo ba, somehow that boy got wind of me in 2004, called my NGO, and asked for me. ‘Kilala daw po n’yo ang tatay ko, si Jude. Nakasama daw po ninyo sa NGO. Graduate po ako ng Creative Writing sa Makiling and I want to meet people who might have known my father.’ Naiyak ako. Though I could not say much about Jude, I did give the boy another lead. I told him I had met him as a toddler with Joker.”

I guess the lesson here is: We all need the courage of one another to be rid of a dictator—whether it is the Strongman then or the Strongman now.

April 2, 2019

Talk delivered at the Ateneo de Manila University (Diliman), during the forum called “PERSONAL STORIES: Writing and Documenting Martial Law,” organized by the Ateneo Department of History and the Ateneo Library of Women’s Writings. For publication, small edits have been made to this speech.

Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon started her journalism career in 1972, the year Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. After joining the Underground and going to prison, she returned to the trade, where she remains today, as editor and author.