Mark of Four Waves

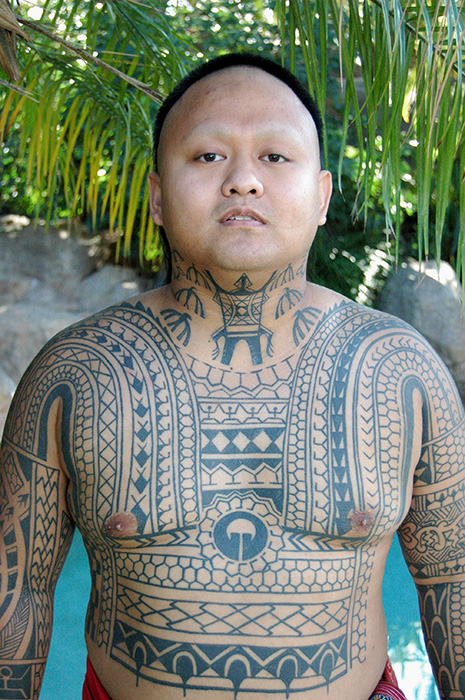

/Members pose at the tribe's shrine in Buena Park, California (Photo by Roger Carter)

The Tribe was founded in 1998 when co-founder Elle Festin of Buena Park, California, and some of his friends went to Hawaii for vacation. There they met some native Hawaiians proudly displaying their heritage through tattoos. Festin wanted to get a Hawaiian tattoo so he went to a tattoo shop owned by famous Tahitian tattoo artist, Po’oino (he tattooed actor Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson). As Po’oino talked about his own Tahitian heritage, his ancestors and their tribal traditions, he challenged Elle to discover his own Filipino tattoo traditions. From this, Tatak ng Apat na Alon was born.

“Tatak ng Apat na Alon is an organization dedicated to reviving the traditional cultures and tattoos of the Philippine Islands,” said Festin. Its translated name, Mark of the Four Waves, is a reference to the “waves” of immigrants who came to the Philippines over many millennia: 1) Afro-Asiatics; 2) Malay-Polynesian; 3) Deuteron-Malays; and finally, 4) the Spanish. “The influences, both good and bad, of each of these waves have combined to create the islands’ culture. Tatak ng Apat na Alon intends to resurrect the positive, repair the negative, and move into the future while keeping its roots firmly planted in the past,” added Festin.

Elle Festin is the founder and leader of Tatak ng Apat na Alon (Photo by Roger Carter).

Long History

Early Spanish explorers dubbed the Philippines La Isla de Los Pintados, the Islands of the Painted Ones. One of the earliest illustrations showed Visayan pintados in the Boxer Codex from 1590. Tangible evidence is also found on the 400 year-old Kabayan mummies that still exhibit their traditional tattoo patterns on their aged skin. Tattooing was prevalent among the people in the Cordillera, Central Visayas, and Southern Mindanao.

According to research conducted by Professor Ikin Salvador of the University of the Philippines in Baguio, tattoos were symbols of male valor. They were earned only after a man had proven his courage in battle against warring tribes, such as between the Ifugao and Bontoc Igorot. Like modern military medals, tattoos were added for each feat of courage. Headhunting was the only reason for tattooing among men.

Ifugao women used designs derived from nature. They had leaf designs tattooed on their shoulder blades below a series of wavy lines and a single line of stars. Grass designs covered the rest of their arms, broken only by the bracelet motif at the elbow, wrist, and back of the hand. Their arms were tattooed more ornately than the arms of the Kankanay, lbaloi, Ifugao, and Igorot women. Tattoos also showed that they were available for marriage and able to withstand the pain of childbirth.

Ifugao men tattooed all parts of their bodies except their backs and feet. Most commonly they tattooed their chest, shoulders, and arms. Common design symbols include: tinagu (man); kinahu (dog); ginawang (eagle); ginayaman (centipede); kinalat (lightning); and the pongo (bracelet). Other designs include the tinungfu (armband) and little men representing the warrior’s status and wealth in his community or tribe. The full chest pieces are called Chaklag. Certain tattoos were believed to provide “protective” qualities or spiritual powers as the warriors went into battle.

"Malakas at Maganda" (Photo by Roger Carter)

As ancient as the Filipino tattoos are, they are among the least known of the Polynesian tattoos to which they share many similarities. “Filipinos have deep connections to other Polynesian cultures. We all have the same common ancestors and we come from the same Austronesian linguistic chart,” said Festin, who majored in anthropology. Words Filipinos share with other Polynesian cultures include – mata (eye); ulu (head); niog (coconut); and kain (food), to name a few.

Unfortunately, the attitude of most Filipinos toward tattoos is not positive. “My parents first said ‘what the hell is that’, they thought it was dirty. In the Philippines, tattoos were taboo. It branded you as a bad person, someone that went to jail,” said Gamy Pascual, Tribe member from Chicago and one of the few immigrant Filipino members. “However, when I told them it was a way to honor my ancestors, they were more proud,” added Pascual.

As ancient as the Filipino tattoos are, they are among the least known of the Polynesian tattoos to which they share many similarities. “Filipinos have deep connections to other Polynesian cultures. We all have the same common ancestors and we come from the same Austronesian linguistic chart,” said Festin, who majored in anthropology. Words Filipinos share with other Polynesian cultures include – mata (eye); ulu (head); niog (coconut); and kain (food), to name a few.

Unfortunately, the attitude of most Filipinos toward tattoos is not positive. “My parents first said ‘what the hell is that’, they thought it was dirty. In the Philippines, tattoos were taboo. It branded you as a bad person, someone that went to jail,” said Gamy Pascual, Tribe member from Chicago and one of the few immigrant Filipino members. “However, when I told them it was a way to honor my ancestors, they were more proud,” added Pascual.

Standing (L-R): Gemy Pascual and the author. Seated: Samantha Juan an Emily Baraan. Tribe members showing off their Northern Cordillera tattoos (Photo by Roger Carter)

Tribal Rules

Tatak ng Apat na Alon members each join for their own personal reasons. However, there is one common denominator among all members -- a thirst to learn more about their Filipino heritage. “From my grandmother, I found out that my grandfather was from Bicol and his last name was Sinon, an Indian surname. I’m also part African American so I’m trying to reach back and bridge the gap between my various cultural backgrounds,” said Jayson Winborn, Tribe member from Bremerton, Washington. He found the Tribe on the Internet.

To become a member of the Tribe, applicants must first write a Letter of Intent to the Amangs (high ranking Tribe leaders). The Amangs will review the Letter of Intent and determine if the person is sincere in wanting to join the Tribe. “We interview prospective members to further determine if they are truly sincere about their spiritual path and their willingness to learn more about their Filipino culture, explains Festin. Once accepted, new members must fill out a questionnaire so that research can begin on their individual tattoo designs and patterns. From the questionnaire, the Tribe will correlate their answers with traditional Filipino patterns and symbols. Every September new members are accepted into the Tribe and others are elevated in rank.

The ranking system of the Tribe is based on the Katipunan system: Anak - black, blue and red; and Amang - black, blue and red. The highest rank in the Tribe is Datu, which no one holds at this time. “We use the Katipunan ranking system, because like them, we are going against the grain,” said Festin. Currently there are about ten Amang Reds, the highest rank thus far. Members earn their rank by promoting the Tribe and knowledge of Filipino culture and tattoos. “We take heads not by cutting them off like our ancestors, but by taking their heads to impart knowledge,” added Festin.

Tatak ng Apat na Alon members stress that their tattoos are not a fad or a fashion statement. The tattoos are intended to bridge the gap to their ancestors making every pattern sacred. Each member's tattoos have story lines and deep symbolic meanings behind them. “I know someone who got a Filipino tattoo which he thought indicated that he was a brave warrior. But what the design actually meant was that he was the widow of three warriors. I didn't say anything to him about it because I didn't want to embarrass him. His heart was in the right place. But that is an example that it's very important for people to know that these tattoos have real power and meaning, and could bring unwelcome things into your life if you aren't absolutely sure what they stand for, or if you aren't the person who is supposed to be wearing them,” stated Festin on the Tribe website.

“Research the patterns and make sure it’s meaningful to you and that it’s not just a fashion statement. It’s a lifelong commitment so make sure it’s something you want,” said Maia Young, Tribe member from Wisconsin and a Polynesian dancer. “My tattoo is my family tree. I can trace my Hawaiian roots eight generations back and my Ilokano roots three generations back,” added Young, an office manager by profession.

This holds true even for famed Filipino American tattoo artist Leo Zulueta, considered the Father of Tribal Tattooing in America and recently featured on the television show Tattoo Wars. “Tattooing has strengthened the connections to my Filipino culture,” said Zulueta from Spiral Tattoo, his Ann Arbor, Michigan, tattoo shop. “I’m proud that my father came over from the Philippines at the end of WWII and that my mom was born in Hawaii. I feel a very close affinity to my culture even though I’ve never been to the Philippines. Elle is the real Father of Filipino Tribal Tattoos because he has done the research,” added Zulueta, with respect to the work of Festin and other Tribe members.

Today, the Tribe has over 500 members in California, Washington, Maui, Oahu, Florida, Nevada, New York and Chicago. It’s also expanding internationally to Canada and Australia. “We get inquiries from all over the world,” said Festin. “I have emails from Greece, Germany and other countries that you wouldn’t think there would be Filipinos. Some forgot their identity and culture and now want to reach out and want to know who they are as a people.”

The many emails Festin receives on behalf of the Tribe have a common lament: my parents never taught me about my culture. I thought Filipinos were Spanish. “For me, it’s important to see that when Spanish got there, colonial mentality did something to our ancestors, then assimilation changed that and we lost their identities. The website is opening people’s eyes and helping them see the light of day through our tattoos. This is who we really are, we’re not trying to be tribal, this is who we are,” said Festin.

Mark of Four Waves website - www.apat-na-alon-tribe.com

Originally published in Filipinas Magazine, February 2008

Update: The Tribe now has its own Tattoo Studio and Gallery called "Spiritual Journey" located at 7159 Katella Ave., Stanton, California. Elle and Zel Festin along with internally renowned guest tattooists will do traditional "tapping" for clients.

Mel Orpilla holds the rank of Amang Red in the Tribe and is the leader of the Bay Area Chapter. The traditional Filipino tattoos are just one manifestation of his Warrior roots. He is also a Master and teacher in the Filipino Martial Art of Balintawak Arnis, is the author of "Filipinos in Vallejo" published by Arcadia Publishing, and the National President of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS). He works as the District Representative for Congressman Mike Thompson, 5th District, CA.