Marcos and Memory

/Malacañang Palace, February 25, 1986 (Photo by Romy Mariano)

I remember being swept in a giant wave of people that crashed through the gates of the now abandoned Palace. Everywhere were signs of a hurried retreat: documents tossed out of a window, emptied jewelry cases, bullets scattered on the floor. On the evening of February 25, 1986, I thought, like so many others, this is the end. The Marcoses had been expunged from our lives. Forever. How wrong we were.

Today I will talk about memory, about fathers, sons, and daughters. About the Marcos family and mine. And how, from one generation to the next, the word is passed.

I was a Martial Law baby. My generation grew up watching the unending spectacle of Ferdinand and Imelda. Remember this was the 20th Century, long before YouTube and Netflix. I would have preferred to watch “Zombie Apocalypse” but that wasn’t an option. There were only five TV channels and three newspapers, all owned by Marcos cronies. We didn’t call it “fake news” then but it was vintage 1970s propaganda – obvious and crude.

Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos

I was in first grade when Marcos was first elected president. I studied across the street from Malacañang, in a school for girls run by the Sisters of the Holy Ghost. I remember that in the 1960s, the streets around the presidential mansion were busy, filled with traffic and commerce. On Thursdays, hundreds flocked to the church nearby to pray to St. Jude, patron of hopeless causes. I was barely in my teens when Martial Law was declared. Suddenly the streets were silenced. The Palace gates were shuttered. Barbed wire barricades kept people away. The neighborhood – the entire country – was hushed.

Marcos was still president when I finished high school. He continued to issue decrees from his barricaded palace while I went off to college, graduated, and got my first job. My generation had reached adulthood with no memory of any other president. Most of us didn’t know that while we were growing up, thousands of dissenters had been tortured, killed, or jailed; that in faraway villages, the army had been let loose to pillage, rape, and murder; that the Marcoses were stealing our money and squirreling it in Swiss banks and Manhattan real estate.

We didn’t read any of that in the news.

Instead, we were entertained. Muhammad Ali beat Joe Frazier in the “Thrilla in Manila.” We had beauty pageants, the Bolshoi Ballet, Van Cliburn, international film festivals. We watched the Marcoses party with Brooke Shields and Cristina Ford. George Hamilton twirled Imelda to the tune of I Love the Nightlife. Gina Lollobrigida photographed Ferdinand. Imee was being matched with Prince Charles. The Marcoses behaved like royalty so we were not surprised when, at yet another Marcos inaugural, the choir sang, “And he shall reign forever and ever,” as the orchestra played Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus. Marcos was the Messiah. How did we think we could get rid of him so easily?

Long history of mythmaking

The truth is that the Marcos mythmaking began long before I was born. Not in my generation nor even my parents’ generation. It began with my grandparents’ generation. Today we blame social media disinformation and the textbooks that glorify or normalize Marcos and Martial Law. But the lies, evasions, elisions, exaggerations were sowed almost a hundred years ago. If they are difficult to weed out now, it is because they are so deeply rooted.

My grandfather, Juan B. Coronel, was born in 1909. He was a school teacher in Sta. Cruz, Ilocos Sur. So was my grandmother, Victorina Pimentel. Marcos’s parents, Mariano and Josefa, were more than 10 years older than my lolo and lola, and they, too, were school teachers. They were all among the first generation of Filipinos to be educated in English, in the public school system set up by the American colonial regime.

Mariano Marcos, Josefa Edralin, and their young family

Mariano Marcos eventually left teaching and took up law and went into politics. In 1935, along with his friend and ally, Gregorio Aglipay, he ran in the first-ever election of the Philippine Commonwealth. Aglipay ran for president against Manuel Quezon; Marcos, as representative of Ilocos Norte in the National Assembly. Both of them lost, Mariano Marcos to his longtime rival, Julio Nalundasan.

Not long after the results were announced, Nalundasan’s triumphant followers paraded around town in cars and trucks. One of them carried coffins with Aglipay’s and Marcos’s names on them. The revelers lingered in front of the Marcos home in Batac and shouted, “Marcos is dead.” For the Marcoses, this was, in the words of the Supreme Court, both “provocative and humiliating.”

We all know what happened next. The following night, Nalundasan was shot and killed. The principal suspect: Ferdinand Marcos, champion shooter of the ROTC rifle and pistol team. He had then just turned 18. A court in Laoag tried and found him guilty but he made an impassioned plea to be allowed to continue his law studies while in jail.

Ferdinand was bad-ass. Here was the valedictorian of his class, acting as his own lawyer and appealing the ruling while studying for the bar. He topped the 1939 bar exams, wrote an 830-page brief to the Supreme Court, and argued his case in an all-white sharkskin suit. He was acquitted and saved from the death penalty. By 1940, the wide publicity given the case had made him a legend.

If you were Ilocano like my grandparents, from a part of the country that was hard-scrabble poor; its people living on land wedged between mountain and sea, famous for their frugality and work ethic, and who valued family and honor, you would be cheering for him, too.

Up to now we don’t know who killed Nalundasan. We do know that Jose P. Laurel, the Supreme Court justice who wrote the decision, was Marcos’s law professor at UP. It was he who convinced the high court to reverse the conviction by arguing NOT that Marcos was innocent but the country needed brilliant young people like him. The justice’s son, Jose III, was Marcos’s classmate since high school and his Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity mate. It was he who drove Ferdinand to Malacañang so President Quezon no less could congratulate him on his acquittal.

Jose Jr., Justice Laurel’s son, would tell me all this when I interviewed him many years later. Like so many other politicians of that era, he liked to tell the Marcos-Nalundasan story. It was legend. This was 1984, confetti was raining down on Ayala Avenue in the protests that followed the assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino. I was a neophyte reporter, and the old man was giving me a lesson on the longevity of political families. What I took from it was something else: their easy embrace of chicanery and political murder.

It was a lesson Ferdinand Marcos had learned at age 18.

Marcos writes own history

Marcos studying for the bar in jail and arguing his case in the Supreme Court. Detail from Botong Francisco mural, “The Life of Ferdinand Marcos,” 1969 (Source: Vera Files/U.P. Third World Studies Center

Marcos did not trust historians. “History,” he wrote in his diary in 1971, “should not be left to historians… Make history, and then write it.” And that, he did.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Marcos was called, like so many young Filipinos, to defend Bataan. When Bataan fell, he joined the Death March and ended up a prisoner of the Japanese in Capas, Tarlac.

My grandfather also fought in Bataan and was in the Death March, but was so sick of malaria, he was left behind in the town of Hermosa. When he recovered, he joined the anti-Japanese resistance, was captured, and executed by the Japanese in his hometown in September 1944. He was only 35 years old.

For many years, my lola kept the documents that attested to her husband’s service: This one said my lolo, Lt. Juan Coronel, a graduate of the ROTC like Marcos, was sent with his unit to defend the coast of Bataan and surrendered to the Japanese at the foot of Mount Samat. It said he was spying for the guerrillas when he was captured. My father, the eldest son, then not quite 11, was the last in his family to see my lolo alive. He told us he went to the plaza just before his father was hanged, and there, my lolo entrusted him with the care of my lola and his two younger siblings.

Unlike Marcos, my lolo didn’t get any medals nor were movies made about his war exploits. He also didn’t have the protection of friends and family in the right places. Marcos did. According to US Army intelligence reports and a diary kept by a Japanese war interpreter, Mariano Marcos had welcomed the Japanese to Laoag and had spoken at a pro-Japanese rally in his hometown. It could be that the older Marcos, like other nationalists, sympathized with the Japanese because they were at war against U.S. colonialists. Whatever the case, some Marcos biographers speculate that Mariano’s Japanese connections facilitated his son’s release from prison in August 1941.

So what did Marcos really do during World War II? Like so many things about the Marcos family, the facts are hard to pin down. Marcos said he cheated death many times during the Battle of Bataan and afterwards, when he led a guerrilla unit, Ang Mga Maharlika,that fought heroically against the Japanese. In 1964, the American journalist Hartzell Spence published a glowing Marcos biography, For Every Tear a Victory, that detailed the young Ferdinand’s cunning and battle heroics.

By the time he was campaigning for president in 1965, Marcos had 28 war medals, making him the most decorated Filipino war hero. But when the historian Alfred McCoy trawled U.S. military archives in the 1980s, this is what they found: Marcos, unlike other decorated officers, got most of his medals by lobbying for them when he was already in public office, long after the war was over. In 1963, according to McCoy, then President Diosdado Macapagal, eager to get Congressman Marcos’s support, awarded him ten medals in a single day.

The records also showed that between 1945 and 1948, U.S. Army investigators had dismissed Marcos’ claims: Maharlika never existed. Its exploits were exaggerated, fraudulent, and absurd. In 1950, the U.S. Veterans Administration found that so-called Maharlika members were guilty of atrocities against civilians and were selling contraband to the Japanese. Marcos himself, according to this document from the U.S. national archives, was arrested by the U.S. Army for soliciting funds under false pretenses but was released at the intercession of Gen. Manuel Roxas.

Ilocano hero

Maharlika and the World War II medals are at the heart of the Marcos Big Lie, the foundation of the myth that helped elect him to Congress and later made him president. My father, Antonio Coronel, who was 32 at that time, was among the millions who voted for Marcos in 1965. He was Ilocano, after all, and a lawyer orphaned by the war. I could understand why Marcos, the dashing hero emerging unscathed and rising like a phoenix from the ashes of the Pacific War, would be so alluring for him and so many others.

The Marcos medals

Antonio Coronel

My father was a probinsiyano who came to Manila to study. Higher education boomed in the postwar years. War reparations and aid revived the economy and provided jobs and education for a rising, urban professional class. In 1955, when my father graduated from law school, Marcos was in his second term in Congress. As the representative of Ilocos Norte, he was eloquent and feisty. The landed gentry who dominated the legislature considered him a promising upstart. He impressed those like my father who had no inherited wealth and saw their education and professional skills as their entree to society. In Marcos, they saw a reflection of their own ambitions. When he said he was destined to be president, they cheered him on.

When he ran for public office after the war, Marcos used his embellished war record to propagate the myth of his invincibility and inevitability. Iginuhit sa Tadhana. It is writ in the stars. This was the title of the 1965 movie, starring matinee idols Luis Gonzales and Gloria Romero, released before the election that made Marcos president. We’ll return to this inevitability later.

Even as he introduced Mad Men-type advertising into a Philippine election campaign, Marcos also cultivated the legend that he had an anting-anting, a magic amulet. His commissioned biographer, Hartzell Spence, amplified this tall tale, writing that Marcos had inherited the amulet from Aglipay, the anti-Spanish and anti-American revolutionary who was a family friend and political ally. According to the legend, Aglipay himself made the incision to embed the anting anting on Marcos’s back before the Battle of Bataan. This gave Ferdinand the power to appear and reappear and to restore the dead to life.

Poster, Marcos biopic “Iginuhit ng Tadhana” 1965

Artist portrayal of Marcos as Malakas in the Filipino creation myth

Marcos made Filipinos believe he was of mythic proportions. Through Aglipay, he was connected to the revolutionary and anticolonial tradition. At the same time, the fictional Maharlika linked Marcos to the noble datus of the pre-colonial age. He was Malakas of the Filipino creation myth. After martial law, he commissioned nationalist historians to write Tadhana, a multivolume history that portrayed him and his New Society as the culmination of our nation’s revolutionary and anticolonial aspirations. Marcos was the end of history. Until now, followers of the Marcos cult worship him in some villages in Ilocandia. They say he is the incarnation of Christ or of Jose Rizal and they await his return.

Even those who didn’t like Marcos imagined him to be more-than-ordinary, a Shakespearian figure. The Hamlet Marcos, agonizing whether to declare martial law or to shoot at the protesters on Edsa in 1986. The Macbeth Marcos, egged on to murder by a power-hungry wife. The Richard III Marcos, who would kill and pillage everything that stood in his way.

If Marcos has such a hold on our collective imagination, it is in part because of the lies and half-truths he and his courtiers have told over and over again until they were accepted as fact. It is because they have sown so much confusion over the facts so that even now, truth seems elusive. The Marcoses have been at this since 1935. Let me say this again: The rewriting of history didn’t begin after the fall.

This mythmaking is one reason why today, many believe we are at the cusp of a second coming. The Second Marcos Coming. The Zombie Apocalypse.

Fascist playbook

When Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972, he borrowed from the fascist playbook: Point to a threat and hype it so that people believe their safety and security are at stake and only the strongman stands in the way of perdition. As Marcos said in the martial law declaration, only he can "save the Republic and reform society.”

When he was elected president in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte, a Marcos fan, would adopt the same fiery and messianic tone. Both men saw themselves as saviors. They believed the country needed a strong leader and disciplined people. They were willing to jail, torture, and kill to save society from unruly and dangerous elements. Even good citizens must be watched, and if necessary, gagged and muzzled. The slogan of the martial law years was “Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan.” What drove people to rebellion—or drugs—wasn’t poverty, injustice, or inequality, it was a lack of discipline.

Here is one example of what that discipline meant. Those among you who are older than 50 will remember, as I do, the days when Imelda Marcos fenced off large parts of the city to hide Manila’s squalor. Even before martial law, many of Manila’s poorest residents had been protesting Marcos infrastructure and “beautification” projects for demolishing their homes and destroying their communities.

Trinidad Herrera was one of the most effective and eloquent urban poor organizers. She was known internationally and had even met with both Marcos and the World Bank, the funder of government projects. When the Pope visited Tondo in 1970, she spoke on her community’s behalf.

Trinidad Herrera (arms raised) at a meeting in Tondo, 1971 (Photo by Richard Poethig)

In April 1977, just before the Marcoses were slated to host a big UN conference, Herrera went missing. After more than a week of searching, her lawyer, former Senator Soc Rodrigo, found her at a detention cell at the Military Intelligence and Security Group. In a letter he sent to top officials, he described what had been done to her:

“She was ordered to remove all her clothes until she was completely naked; then she was made to attach and wind, by herself, around her left nipple, the end of one of two electrode wires. While electric shock was being applied on her nipple, one of the torturers was holding the other electrode in front of her vagina—uttering threats that if she still would not ‘cooperate,’ he would attach [the] wire to her vagina.”

I never met Trining Herrera, but I have a vague memory of briefly meeting the two lieutenants, Eduardo Matillano and Prudencio Regis, who she said tortured her. Their lawyer was my father, Antonio Coronel, who often met his clients over breakfast at the family table.

Few torturers then or since have been brought to trial. But the case got wide publicity in the U.S., where Congress was debating whether to slash military aid to the Philippines because of human rights violations. The military was forced to bring Matillano and Regis to a court martial. My father defended them and they were acquitted. Years later, he would also defend Marcos’s chief of staff, Fabian Ver, when he was tried for the assassination of Senator Aquino, and, after the fall, Imelda Marcos, who was being sued for the family’s legendary ill-gotten wealth.

My father’s clients

I had frequent arguments with my father about his choice of clients. His answer always was: Even the guilty have the right to a proper defense. He was a criminal defense lawyer, he reminded me. His job was to defend criminals. He was called in AFTER a crime had been committed, unlike corporate lawyers, he said cheekily, who are consulted BEFORE the crime.

He was a charming rascal, my father. He could argue his way out of anything. He teased me about my objections to his clients but not to the shoes and dresses his lawyer’s fees bought me. He also told me that Marcos had asked him to rein in his journalist daughter. He supposedly said something like, I can do that if you can restrain Imee. Being my father’s daughter gave me some protection. Did it also give me the courage to do the kind of reporting I did, more courage than I actually had?

My father was not a Marcos loyalist. He wasn’t blind to the excesses. But like a lot of smart men of his generation, he was drawn to Marcos, like moths to a flame. Adrian Cristobal, after whom this lecture is named, was a renowned literary figure before becoming Marcos’s speechwriter. He brought other writers into the Marcos fold. Blas Ople, ex-socialist, ex-journalist, was among the smartest and most self-aware of all the president’s men. He told me, not long before the fall, when there was fierce in-fighting in the Malacañang snake pit – Marcos is like a banyan tree that keeps everything under its shade, so nothing grows underneath it. And yet, he, too, couldn’t leave the shade.

Smart as they were, these men could not resist the allure of power, the money and privileges that came with it, and the giddiness of basking in the sovereign’s glow. Marcos knew how to flatter their egos. His ambition, his virility, charm, and wit, his ease with power were irresistible to a lot of men – and women, too. The appeal of the strongman, of fearsome and unaccountable power, is nearly universal.

The Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley, whose parents fled Nazi Europe, wrote, “Fascism is not a new threat, but rather a permanent temptation.” To fight it, he said, we must resist normalization. Here I quote from his book, How Fascism Works: “What normalization does is to transform the morally extraordinary into the ordinary. It makes us able to tolerate what was once intolerable by making it seem as if this is the way things have always been.”

This bears repeating: “What normalization does is to transform the morally extraordinary into the ordinary. It makes us able to tolerate what was once intolerable by making it seem as if this is the way things have always been.”

Marcos Jr’s platform

Which brings us to Ferdinand Marcos Jr., whose platform, if he has one, is the normalization of Marcos. Like his father in 1935, he is seeking to redeem the family honor and avenge his family’s fall. Like his father, he is erasing and rewriting history. He is also propagating the myth of his electoral invincibility and the inevitability of his presidency.

Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. is sworn in as special assistant to the president, 1979

Those seeking to explain why another Marcos may become president say it is because we have failed to hold the family to account. We did not de-Marcosify the country. We sent the Marcoses to exile and then welcomed them back. De La Salle political scientist Julio Teehankee faults the political elites who helped restore the Marcoses and their allies to power through elections. He blames the weak party system that allowed for the “authoritarian contamination” of our political life.

Sociologist Jayeel Cornelio of the Ateneo says the Marcoses are masters at selling fantasy and the promise of restoring greatness. Others attribute Junior’s stickiness simply to money, machine, and social media. They credit his image makers for marketing Junior as the pale, bland, harmless version of his father. Acceptable even to the pearl-clutching Cory matrons. Just as pinakbet without bagnet is acceptable to vegans.

Some put the onus on the opposition for being disunited, underfunded, and weak. Others despair about Marcos nostalgia and magical thinking – the promise of a shower of Yamashita or Tallano gold at the end of the election. Many, especially among the educated, say it’s because uneducated voters cannot see through the fog of disinformation. The hyper-educated point to world-historical forces – the erosion of democracy globally, the distrust of liberal elites, and the growing inequality that drive citizens to the autocrats’ embrace.

All these explanations have the ring of truth, but they also have something else in common: They paint an unflattering picture of us and our fellow citizens. It’s as if we are all passive receptacles of Marcos propaganda or social media manipulation. We’ve either been conned or seduced by the Marcoses. Or we’re pawns of a history not of our own making. By telling you about my family’s story, I may have succumbed to this, too. Guilty of the narrative that exonerates the Marcoses by saying all of us are at fault, we were all complicit. Or blameless because history is to blame. The fault IS in our stars.

But resisting normalization means resisting disempowering narratives. It means not being content with the consolation offered by explanation. While agonizing over this lecture, I had a dream that I was desperately trying to write on a piece of ruled paper but there was no ink coming out of my pen. I was frantic, but the harder I tried, the more I failed. Either the pen wouldn’t write or the paper would be too damp to write on.

You can interpret this dream however you want. To me, it was a nightmare of disempowerment, the sense that wherever I go, I cannot escape history, I cannot flee from Marcos. Even here in New York.

I walk down Fifth Ave. past Tiffany’s and I think not of Audrey Hepburn having breakfast there but of Imelda Marcos shutting it down so she could shop undisturbed for HER jewelry with OUR money. Farther south, just beside St. Patrick’s Cathedral, is Olympia Towers, where Imelda had a seven-bedroom condominium on the 43rd Floor. Severina Rivera, a Fil-Am lawyer assigned to hunt for Marcos assets, told me she found paintings of old masters hidden under the beds there. One of them, by the French artist Fontin-Latour, was auctioned in 1987 for $400,000.

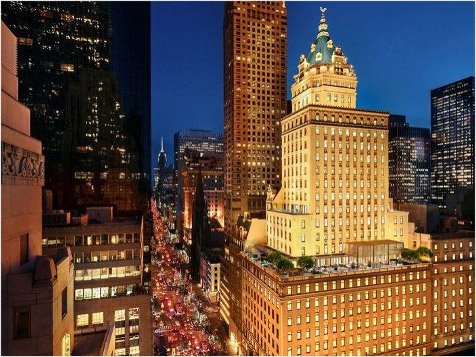

Crown Building, New York City

At night, if you are in a tall building with a view, Manhattan glitters like a box of jewels, irresistible to Imelda. In the 1980s, she bought four buildings here, including this jewel near Central Park, with its copper pinnacle that lights up at night.

Some years ago, I sat in a Manhattan courtroom to watch the trial of Vilma Bautista, Imelda’s personal secretary. In the 1980s, Bautista kept meticulous records of Imelda’s shopping and the millions of dollars withdrawn from the Philippine National Bank in New York to fund her sprees. By the time I saw her, Bautista was a frail, broken woman who shuffled to the courtroom, always dressed in black. The court said she had taken four Impressionist paintings from Imelda’s town house, sold Monet’s “Water-Lily Pond” for $32 million, and lied about it on her taxes. In 2017, when she was 78, she started a six-year jail sentence. That same year, Imelda turned 88. Two years later she would celebrate her 90th birthday at a roaring party with 2,500 people at a sports stadium. And yes, hundreds of partygoers got food poisoning.

All this fuels my fevered nightmares. Marcos is a hungry ghost. He torments our dreams, lays claim to our memories, and feeds on our hopes. It’s going to be okay, I hear the ghost saying. The second coming will not be a murderous tyrant. Just a cotton-candy confection spun by PR consultants and TikTok influencers. My son is not Macbeth. He’s only Pinoy Big Brother.

You will be in La-La Land, a country without memory, without justice, without accountability. Only the endless loop of one family, the soundtrack provided by Imelda.

Action instead of explanation

It is time to hush this ghost. A Marcos return is inevitable only if we believe it to be. If we surrender our power and agency. If we accept explanation instead of action.

I have nothing personal against Ferdinand Jr. He is only a year older than me. I don’t resent the fact that when he was 22, he was made governor of Ilocos Norte, while I was freelancing and trying to get a staff job in a newspaper. My father did write a letter introducing me to one of his editor friends. The editor didn’t seem impressed by either him or me; I never got a response.

I am sleepless because of what the Marcoses represent – world-class plunder, torture, and murder – with no acknowledgment, no apology, no repentance, no attempt at restitution. Not even taxes paid on inherited stolen wealth. And yet, here they are, performing civility and restraint, telling us to chill.

On this night 35 years ago, I stood outside the massive iron gates of Malacañang Palace. In the months and weeks before that night, the most erudite observers were telling us there was no way Marcos would go away. But in 1986, we proved them wrong. Filipinos asserted their agency against the weight of power and the forces of history.

So today, wherever we are, we must remember this: We took down a dictator. Sure, we botched it afterwards but that doesn’t change the fact that we ousted a tyrant. 1986 was an end even if not The End. It was a time of astonishment and possibility. We had a sense that history was being made and we had a hand in its making.

Make history, Marcos wrote in his diary in 1971, and then, write it. We made history and we can do so again. And this time, we should make sure WE write it. We should make sure we RIGHT it.

Note: The lecture begins at around the 32-minute mark.

This was delivered on Friday, February 25, 2022 (US time) as this year's Adrian E. Cristobal Lecture. Posted with permission from Sheila Coronel and Celina Cristobal.