Manila Hotel: The Golden Years

/My mom, Carlota, in front of our store Gem Gift Shop on the Escolta.

She opened stores on Mabini, in Cubao and within the lobbies of the Bayview and Manila Hotels. Now 16, I had the use of our family car. I would drive to school, then in the late afternoon would park out on Katigbak Dr. in front of the Manila Hotel to bring her back home in the evening. Sometimes I would bring my swimsuit and sneak into the pool area, which was reserved for guests of course. It made me feel somewhat privileged … like I was somebody.

Manila Hotel swimming pool-1950s.

There was something about that hotel, catering to the elite that exuded… magic. Years later, in 2004, Michelle and I made a balikbayan trip back to Manila after over 50 years to film scenes for our documentary “Victims of Circumstance”. I insisted we stay at the Manila Hotel to enjoy its service and history. It seemed a bit run down, like an older spinster aunt trying to keep up appearances, but I was not disappointed. There is much to write about the Manila Hotel and much has already been written in great detail. This article is not meant to be a thorough dissertation but glimpses captured from the timeline of its over 100 year history. I hope you’ll indulge me and enjoy this article. Oh by the way, there’s our 55 Chevy parked out in front.

The Beginning

At the turn of the 20th century, Manila was a busy hub of newly arrived American and European businessmen eager for the opportunities this country offered but accommodations were lacking. There were several larger and older hotels such as the Hotel Oriente, the Delmonico, the Metropole and the Bayview but they could not be classified as “first class hotels” by any means.

This was the original Bayview hotel on 13-29 Calle Alhambra. It would later be torn down with the widening of Dewey Boulevard. Realtor Harry Kneedler rebuilt the new Bayview in the 1930s.

Original Bayview Hotel-1903 (courtesy of N. Torrontegui)

“In the early days the Bayview was the fashionable evening resort of Manila. Special dinners, at two pesos a cover, were served Sunday evenings, and a large orchestra played during dinner. The dining room in the little hotel on Calle Alhambra would be literally thronged with people, and victorias and calesas would line both side of the street outside. In those days there were but few automobiles in Manila.” [The Spokesman and Harness World Vol 29 – July 1913 Page 347]

Hotel Oriente

The older hotels were located at sites not immediately accessible; hidden away within the Intramuros or in the Binondo area, and the food and service were mediocre at best. The Hotel Oriente was owned and managed by Ah Gong, a food provider whose warehouse was next to the Quinta market.

La Quinta Market

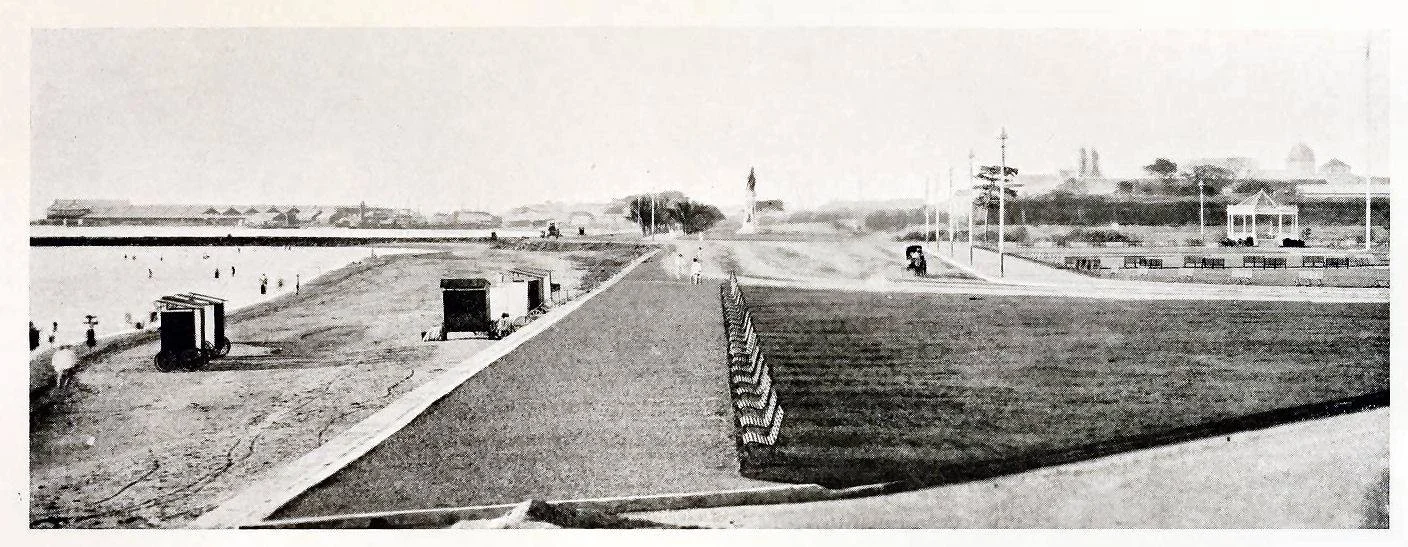

The Philippine Commission brought over architect Daniel Burnham to “beautify” the city. His plan was magnificent as it transformed the old mosquito ridden and water-filled moats around the Intramuros into a sunken gardens and public golf course. These rare photos shows what the Luneta looked like before the landfill extension.

The Luneta prior to the landfill. In the distance, center, is the Legazpi-Urdaneta monument next to Bagumbayan (Bonifacio Drive). You can see the bay come right up to the road.(Photo courtesy of John Tewell)

Looking southward from about the same position. Dewey Blvd, the Luneta Hotel, Elks Club and Army Navy Club have yet to be built. (Photo courtesy of John Tewell)

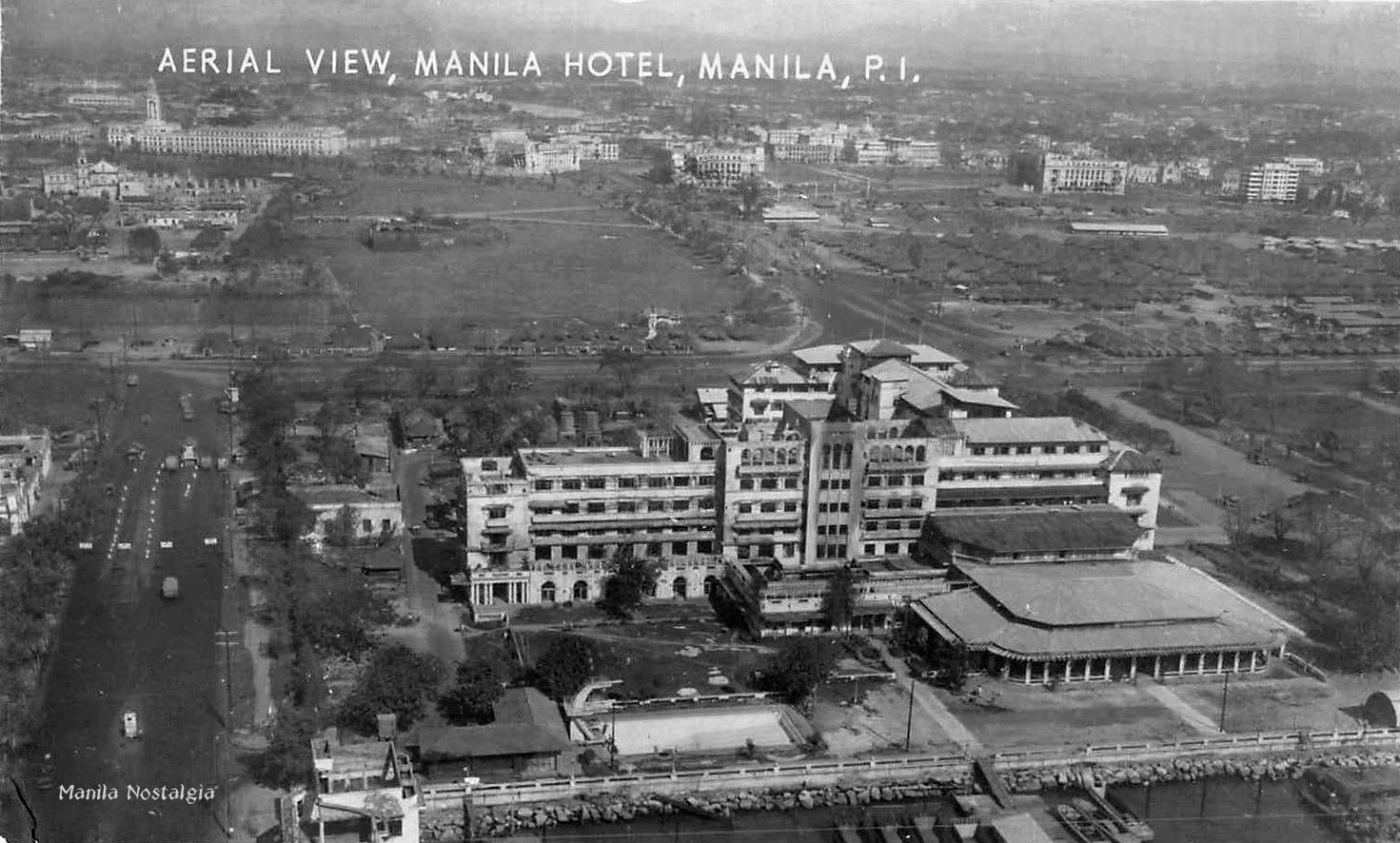

Pier 7 at the bottom of the photo. The Manila Hotel is the white structure in the middle. (courtesy NASM Archives)

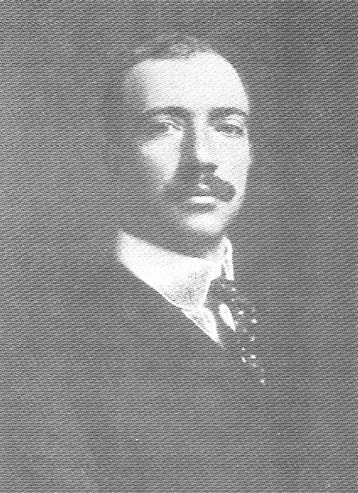

The harbor was dredged and millions of tons of mud and sand were used to reclaim and extend the Luneta, making room for the Elks Club, the Army Navy Club and a site for a first class hotel to be called the Manila Hotel. The location was perfect as it was next to Pier 7, where it was now possible to berth four large passenger ships at once and visitors could find a room just a short calesa ride away. Burnham commissioned American architect William Parsons to design the Manila Hotel as well as many buildings which still stand today: the Elks Club, Army and Navy Club (barely standing), PGH, Paco Railroad station, and the Paco Market.

Architect William E. Parsons

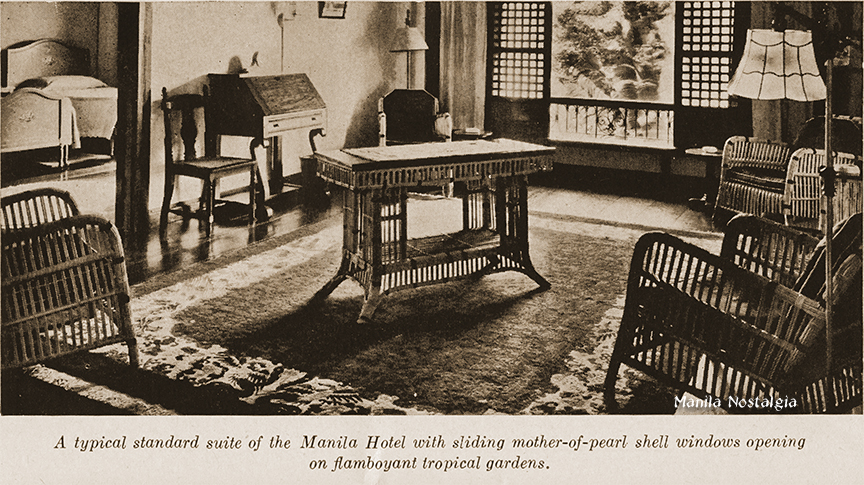

Architect Parsons selected a “California Mission” style for the new hotel, essentially a large, white-washed concrete house with a deeply pitched, cool green tile roof. A circular rotunda led up to the main entrance and portico.

The new Manila Hotel, c.1915

Framed by graceful twin Doric columns of white plaster and arches, the lobby had double grand stairways which led to the mezzanine floor that included a music room, guests’ parlor, and children’s dining room (a Victorian convenience which greatly added to the adults’ leisurely dining).

The long-awaited opening of the Manila Hotel, hailed as the “finest hotel in the Far East,” occurred July 4, 1912. [The Manila Americans, Lewis Gleeck, Jr.]

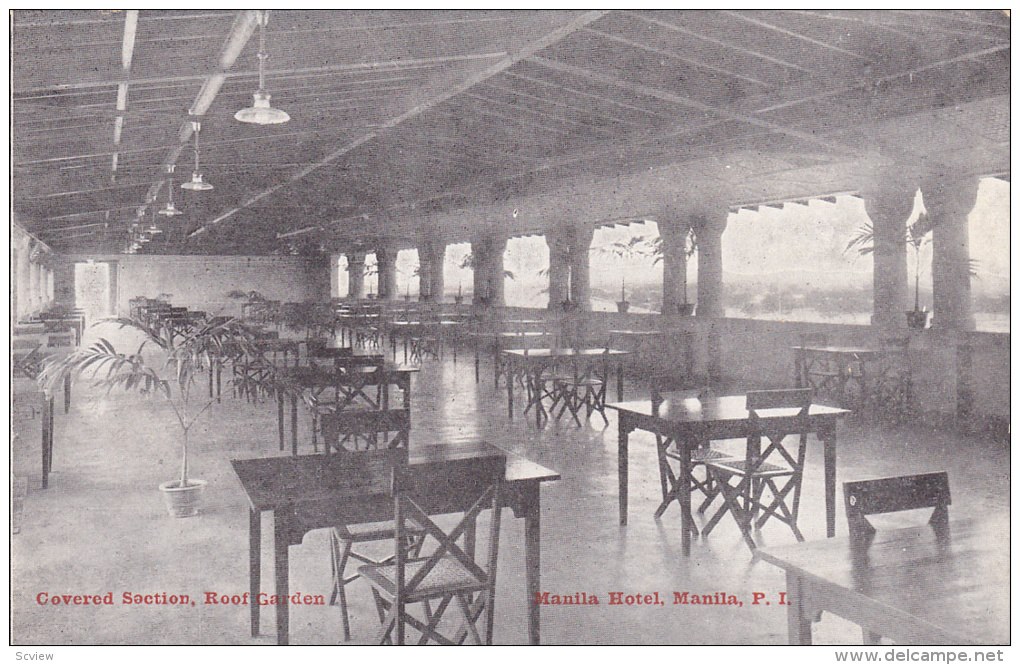

“The Manila Hotel (and I want to say this grand new house would do credit to any city in the United States) is a reinforced concrete building set in the center of a large park or parade ground. The house has a handsome roof garden; indeed nearly the whole roof is garden. Two Otis & Co. lifts took the tourists to the roof where long tables were set, loaded with tea, fruit, native and foreign; sandwiches, cake, and an army of native waiters ready to serve all.” [Notes Made during a Cruise Around the World in 1914- R.H.Casey]

Newly built, the Manila Hotel in 1913 framed against Manila harbor.

The Men’s Loggia at the front of the building was a favorite lounging room for smokers as it gave a view of the Bay and the incoming visitors. At the back was the bar, cigar counter, haberdashery, and grill room.

Manila Hotel-Men’s Loggia looking towards main entrance-1914 (Photo courtesy of Cherry Diolazo)

The main dining room reached from the left end of the lobby, swept in large semi-circle out toward the bay so that each guest could dine with an uninterrupted view of the strikingly vivid sunsets of Manila Bay.

Measuring 97 by 75 feet, the high-ceiling room was surrounded by a spacious open veranda that could be used for dancing. “Quite naturally, all hotel guests wore coat and tie for dinner every evening, sometimes tuxedo. The meals were accompanied by dinner music.” [Mabuhay: Coming of Age in the Philippines, John S.D. Eisenhower]

It was a five-story building with 149 guest rooms which began on the second floor, half of them having their own private bath, an unheard of luxury for that day. There were telephones in every room, push-button room service and the first intercom system installed in Asia. No air conditioning was available as yet so the guests relied on ceiling fans and open windows for ventilation. The hotel was so popular, an annex designed by Andres Luna de San Pedro, was later built on the bayside to accommodate an additional 80 guests.

To provide a pleasant spot to collect the cooler breezes wafting from the bay and perhaps to enjoy a music program offered at the Luneta grandstand every evening, Parsons designed a roof garden.

The Thirties (I should have said the Thirsties !)

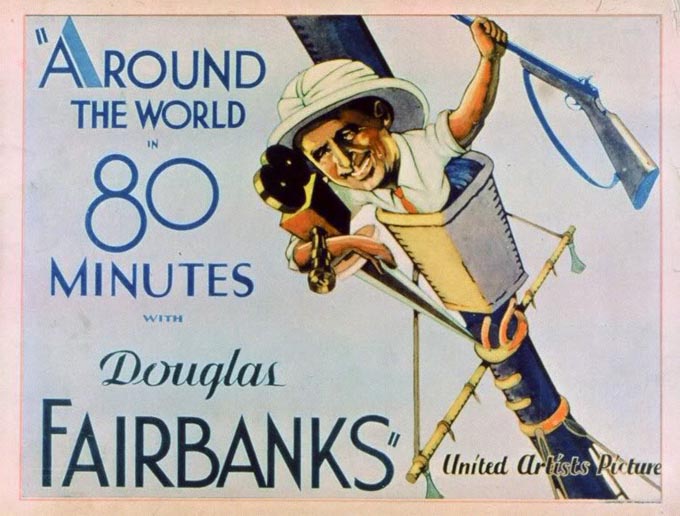

1931 was a changing point in the lives of director Victor Fleming and actor Douglas Fairbanks Sr. While the golden years of the director were yet to come, the ultimate star of the silent movie era was facing the rapid decline of his career with the advent of the talking pictures. Fairbanks decided to produce a documentary titled “Around the World in 80 Minutes” as a desperate escape from Hollywood and a disloyal cinema audience.

Many of the hotel staff sneaked down to the lobby to see the famous actor and he did not disappoint. Flashing his famous toothy smile, he waved at his audience and vaulted over the staircase with one hand. While Fairbanks was staying at the hotel the management had to station several policemen at the lobby entrance to hold back the crowds.

On the roof garden, Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. was entertained by Manila’s social elite during his 1931 visit to Manila and stay at the Manila Hotel (courtesy Ted Cadwallader)

In the golden days of the 1930s, Manila was as gay and almost as star-studded as Hollywood; its social life was on a stupendous and colossal scale that resembled nothing more than a motion picture set. Celebrities of all shades – in saris, kimonos, satins, fez and regimentals strolled through the lobby of the famed Manila Hotel.

Reception for General Wood hosted by Charles Cotterman on October 24, 1921 (Photo courtesy of A. Butler)

The Manila Hotel, with its roof garden, grill room and dancing was the center of more sedate, mixed social life, though Americans and Filipinos still tended by choice to segregate themselves except at official functions. “It was a life of garden parties by the light of fantastic Philippine lanterns, of buffet dinners for 250 guests, of balls and official gatherings at the Manila Hotel, when the Filipinos indulged their love for lights by stringing them through the vines.” [The Palm Beach Post-Times Sunday May 20, 1945, by Emilie Keyes]

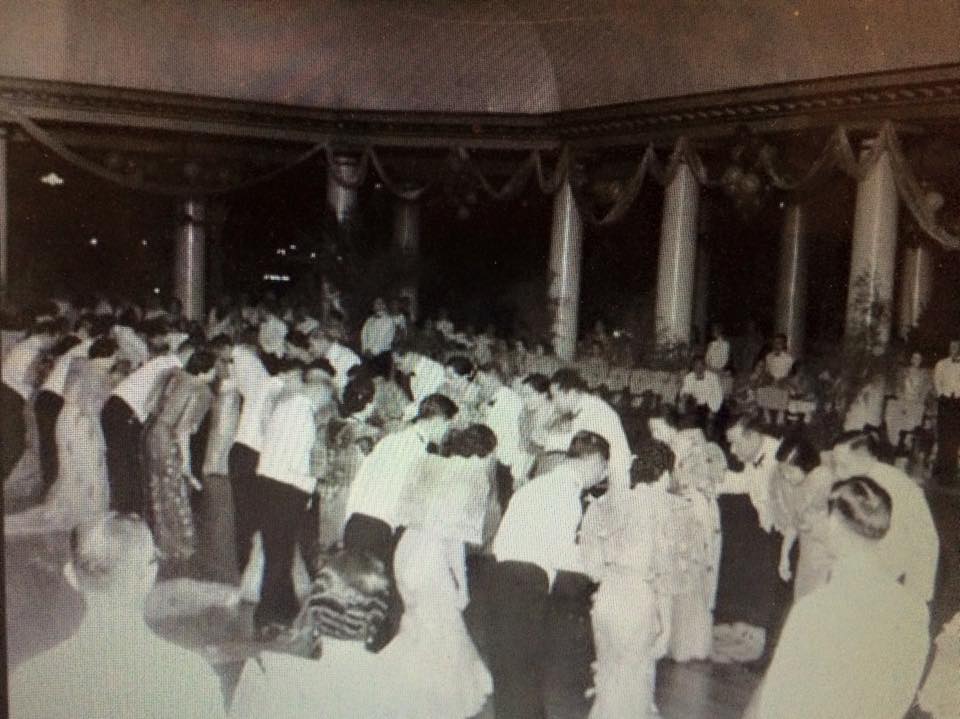

The Kahirup organization, founded by Dr. Manuel Hechanova in 1923, was a social group of sugar barons whose aim was to bond with people of similar elite status. They held an annual ball, typically at Manila Hotel’s Fiesta Pavilion or Winter Garden. It was the highlight of the social season with a fashion show and opened with a Spanish ceremonial dance, the rigodon de honor, featuring high society ladies glittering in their jewels and uniquely beautiful, specially designed,ternos. The rigodon was a delight to watch. It was stately and elegant as a minuet, basically a square dance, danced to the rhythm of a military march.

Kahirup Ball 1934 (Photo courtesy of Isidra Reyes)

Rigodon de honor-1934 (Photo courtesy of Isidra Reyes)

One of the more colorful characters to emerge from the long history of this hotel was Walter E. Antrim who showed up in Manila in the early 1920s and snagged a job as a dishwasher.

By 1926, he had been elevated to Manager of the hotel. “Monk” Antrim knew how to live life in his own way: high, wide, and handsome, making many friends as he went along. He vanished several years later but left his legacy, the “Monk Antrim Lintik Cocktail”. The Lintik drew its name from the Tagalog word for Lightning. It had to be aged for two weeks then chilled in an ice bucket without coming into contact with ice. Antrim married and left Manila suddenly. One can only imagine due to some mysterious reason. He ended up in Mexico and passed into oblivion.

The General

Of course the most famous visitor to this hotel was Gen. Douglas MacArthur. First coming to Manila in 1903 to oversee the construction of fortifications and harbors, he had met a young Manuel Quezon, a lawyer already active in national leadership. The two hit it off and began to have a lifelong friendship. The general returned to Manila in 1928 for two years’ duty, he found his friend Quezon was now a dominant political leader.

General Douglas MacArthur-1932

After Quezon became president of the Commonweath, he asked MacArthur to take charge of a defensive force as Military Adviser in the Philippines. President Roosevelt, eager to get rid of the troublesome MacArthur, agreed. The General established himself to the rank of field marshall, the only U.S. Army office to hold that grade and demanded ₱33,000 salary a year (the same salary and allowances of the High Commissioner of the Philippines) and accommodations to equal Malacañang: seven bedrooms, a special study, and a state-sized dining room. He also required his personal physician, Capt. Hutter and his wife Callie, live in the hotel as well.

Quezon and MacArthur

Quezon commissioned architect Andres Luna de San Pedro to find suitable digs for the general. It was Luna who came up with a solution, “I have looked over the Manila Hotel and I think that if we build a penthouse over the entire top floor of the hotel, we would be able to provide all the rooms and accommodation which the General specified.” The roof garden was turned into a sixth floor with a fully air-conditioned penthouse. In order to justify its extravagant rental expense Quezon’s aide, Jose Vargas suggested appointing MacArthur Chairman of the Board and President of the Manila Hotel Corporation.

The penthouse had as much floor space as the entire floor below, containing the seven bedrooms plus a study, music room and formal dining room. The entire floor was fully air-conditioned and fully carpeted, even rivaling the presidential palace. The remodeling was completed in 1937. The photo below shows the 6th floor addition along with the new annex on the bayside.

(Photo courtesy of Simoun – Philippines, My Philippines)

General MacArthur referred to his brief years spent at the beautiful penthouse with his wife Jean and son Arthur, as one of the two real homes of his entire life.

Jean MacArthur and son Arthur at Manila Hotel – January 29, 1940

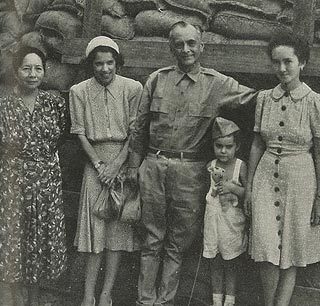

Along with MacArthur came his aide and future president, Lt.Col. Dwight Eisenhower and his wife Mamie and son John.

Dwight, Mamie and John Eisenhower in Manila. Aug. 1937

They were also ensconced at the Manila Hotel. Not as luxurious as MacArthur’s penthouse suite, “the master bedroom had two twin beds, a rather bleak sofa, and enough tables and chairs to serve as a sitting room. Since the apartment lacked air-conditioning, each bed came equipped with a large, cloth canopy overhead, and from it draped a curtain of netting material that was tucked tightly under the mattress on all sides. The fabric of the net was thin enough to make it translucent but finely knit, proof against the smallest bugs.” [Mabuhay, John S.D. Eisenhower]

It was a contentious relationship at best. Eisenhower said, “Yes, I studied dramatics under him for five years in Washington and four years in the Philippines.” The Eisenhowers finally left Manila in December 12, 1939 – just two years to the date before Manila was attacked.

Mamie Eisenhower pins the Philippine Distinguished Service Star on her husband, Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower as Pres. Quezon looks on. This was at the ceremony marking the conclusion of his service in the Office of the Military Adviser to the Philippines, held in the Social Hall of Malacañang Palace. (thanks to Manolo Quezon)

Eisenhower pinned by Mamie as Quezon looks on-1939.

Discrimination was a part of the American colonial period. It existed in clubs like the Army and Navy and Polo Clubs, at cabarets like the Lerma Cabaret and even in the hotels, such as the Manila Hotel.

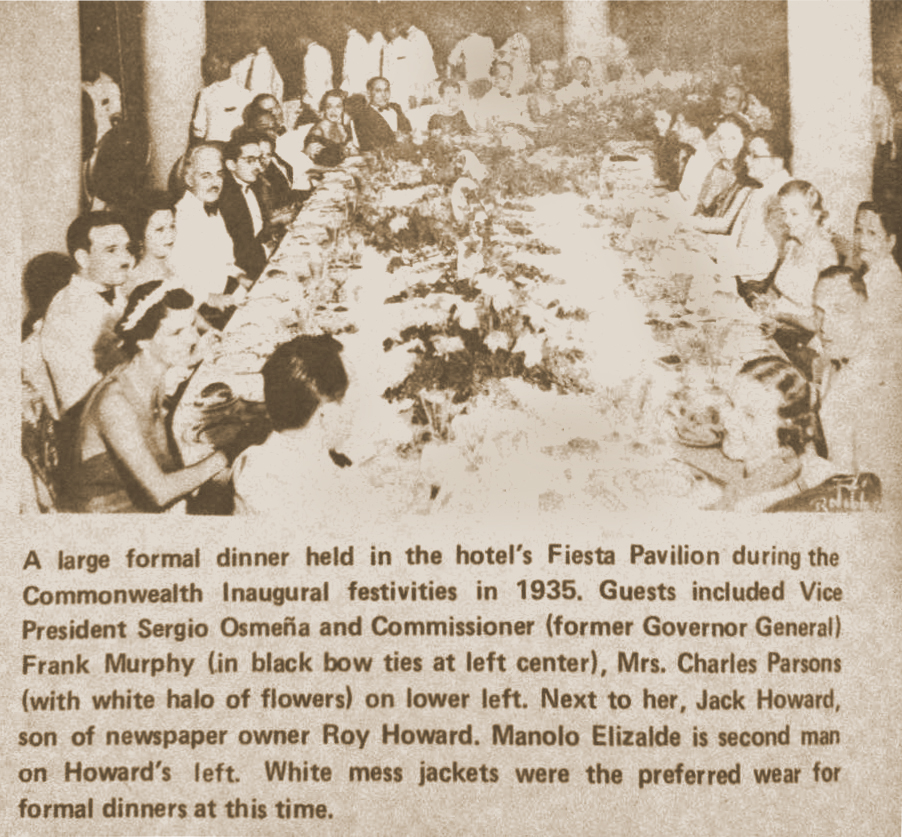

However, after the inauguration of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, the Filipinos began feeling their country was their own, especially with a Filipino living in the Presidential palace. The clubs and hotels had given way to desegregation. Although predominately white, the Manila Hotel now welcomed Filipinos and other Asians as guests. Local residents were seen in the lobby, coffee and barber shop making use of the hotel’s facilities and services. And for the first time, a Filipino, Francisco Mendoza, had been appointed assistant manager. “Americans and Filipinos did not seem to mingle much, although Dad sometimes entertained members of the Philippine government for dinner at the hotel.” [Mabuhay, John. S.D. Eisenhower]

As more and more Filipinos felt comfortable patronizing the Manila Hotel, even the menus offered at the restaurants changed accordingly. From a purely American fare, the food was now an eclectic offering of Filipino specialties such as adobo and pansit to Quezon’s favorite: the Spanish lengua estofada.

Two major events happened in 1935 that were closely tied with the Manila Hotel. On November 15, 1935, the country began as a new Commonwealth of the United States with Manuel Quezon being sworn in as president. There were too many guests to fit into either the Manila Hotel ballroom or Malacañang Palace so the inaugural ball was held in the giant auditorium at Manila’s city fairgrounds. However from that point on, official and semi-official functions of the new Commonwealth government were either held at the Malacañang or the Manila Hotel.

The second event was the inaugural flight of PanAm’s Clipper arrival in Manila Bay on November 29, 1935.

PanAm Clipper lands-Nov 1935 (Photo courtesy of NASM)

With the advent of regular air service to Manila and now only taking 5 days, more visitors and often times, famous guests, would stop to see this “Pearl of the Orient” and stay at thegrande dame hotel of Asia. In 1939, world heavyweight boxer Jack Dempsey arrived to throngs of well-wishers. Ernest Hemingway and his latest (third) wife, Martha Gelhorn, stayed at the hotel. A reception was held in his honor. When asked what he thought of his stay at the legendary hotel, Hemingway quipped: “If it’s a good story it must be like the Manila Hotel.” (source: Isidra Reyes)

Ernest Hemingway at the Manila Hotel

The Manila Hotel lobby was the PanAm office where passengers would make reservations and drop off their luggage for the launch out to the Clipper, moored at Canacao Bay, Cavite. My dear friend, Doug Willard , who worked for PanAm, did double duty as he made reservations, checked in luggage and helped the passengers aboard the Clipper.

Doug Willard – PanAm agent -1940

The PanAm Clipper

In the 1930s, Filipinos danced to swing music performed by jazz dance bands in dance halls around the country. Jazz was played during social events and fiestas, and was widely heard on local radio. Popular bands during this period included the Shanghai Swing Masters, Pete Aristorenas Orchestra, Cesar Velasco Band, Mabuhay Band, Lito Molina with the College Boys Orchestra, and the Tirso Cruz Orchestra

The Fiesta Pavilion

When the roof garden was converted into MacArthur’s penthouse floor, the main floor dining room was expanded to a full-scale supper club, the Fiesta Pavilion with the entire center area devoted to a dance floor. It was called “the most attractive dining and dancing resort in the entire Far East”.

Lito Molina (extreme right) with the College Boys Orchestra-Manila Hotel (Pinoy Jazz Traditions-thanks to I. Reyes)

War Looms

As the war in Europe raged, storm clouds gathered over the Pacific Rim. Japan continued its onslaught throughout China and Korea and was headed south towards Hong Kong and the Philippines. In Manila, blackouts and air raid alerts were common place activities. Japanese and even German civilians were interned at Bilibid for two weeks. Guests at the hotel took it all in with a certain laissez-faire.

On the evening of December 7, 1941 a loud party was underway at the Manila Hotel’s Fiesta Pavilion. Major General Lewis Brereton, commander of Army Air Forces in the Far East was attending a party thrown by the 27th Bomb Group, recently arrived from the US ahead of their planes. The party, marked by raucous laughter, off-key singing, tinkling glass, and squealing girls would continue into the wee hours of the morning. Observing from the Hotel’s Bamboo Bar under a cascade of scarlet bougainvillea, First Lieutenant Dwight Hunkins of H Company remarked to his friends, “I hope they can fly B-17s better than they can sing.” None of them knew it yet but they would be at war the next morning and when it was over only one of them would still be alive. [Soldier’s view of attack on Manila, www.31stinfantry.org]

As Gen. MacArthur was having breakfast in his suite on Sunday July 27, 1941, he received a cable from President Roosevelt recalling the general back to active service. Five months later on December 8th, Manila was attacked by the Japanese and the rest is history.

Aurora A. Quezon, Jean Faircloth MacArthur, Manuel L. Quezon, Arthur MacArthur and Maria Aurora Quezon, during a reprieve in the daily bombardment on the island fortress of Corregidor, 1942.

MacArthur, Quezon, Romulo and others retreated back to Corregidor and left for Australia as defeat was imminent, leaving Jose Laurel, Jorge Vargas and his remaining administration left to manage a puppet government set up by the occupying Japanese forces.

In order to save the city from destruction, Pres. Quezon declared Manila an “open city” on December 26, 1941.

Occupation

The Japanese entered Manila on Jan 2, 1942. After a brief period of high anxiety, life seemed to settle back to normal. In order to cut the Filipinos off from Western – American influences and remold them to the new order, the Japanese controlled all forms of media: newspapers, radio and even typewriters and mimeograph machines had to be registered. The Japanese established very strict rules and discipline regarding civilian registration and criminal activity but for the most part, the Filipino with his bahala na (go along) attitude went along with the prevailing winds of the Co-Prosperity Sphere touted by the occupying force, secretly hoping for a miracle rescue by the United States.

Japanese frisking Filipinos (Photo courtesy of Presidential Museum and Library)

The American and British guests at the hotel were ordered to pack one suitcase and enough food for 3 days and to leave their other belonging at the hotel. On January 4th, they were rounded up and sent to the University of Santo Tomas for internment. An arrangement was made to store their bags until they could later be returned to their owners. However, in September when the bags were to be retrieved, the Manila Hotel (now under the management of the Military Administration) demanded payment for outstanding accounts at full rates from the time the rooms were vacated on January 2nd until the internees were taken to Santo Tomas on the 7th. Hotel Manager Mendoza replied that there was little he could do as he was only carrying out his orders. The Manila Hotel guests were lucky to receive their belongings mostly intact where luggage from other hotels had mysteriously disappeared.

Japanese occupation forces in Manila yesterday took over private hotels and some public buildings as temporary quarters for the troops. Among the hotels ceded to the Imperial Army forces were the Manila Hotel, Bayview Hotel, Avenue Hotel, and Central Hotel.[Filipinos, Aliens Urged to Carry On, article in The Tribune – January 4,1942- Surviving the Rising Sun, Liz Irvine]

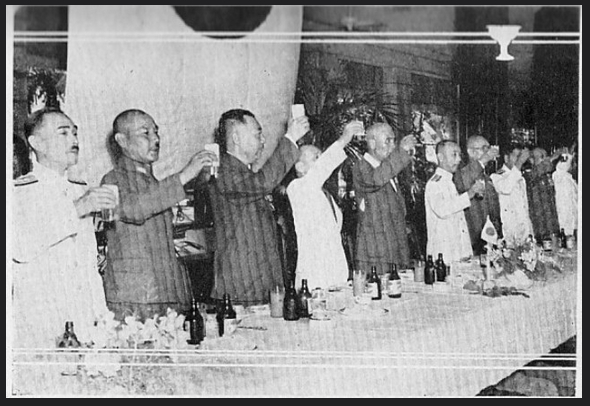

The Japanese Military Administration took possession of the Manila Hotel converting it into a military headquarters for high-ranking officers. MacArthur’s lavish penthouse was used for visiting dignitaries from Tokyo, notably General Yamashita and Prime Minister Tojo, who stayed at the MacArthur suite in May 1942.

It was strange to see the Japanese flags flown at the hotel entrance and other buildings such as the former High Commissioner’s Office. The Filipino staff were ordered to stay on duty and were all forced to learn Japanese. The Chinese chefs were instructed to prepare only Japanese food for the new tenants. The former manager, Howard Cavender had been called to active duty and his assistant, Francisco Mendoza, took over as acting manager – the first Filipino in that capacity.

Prime Minister Tojo and Catholic clergy at Manila Hotel-1942 (Photo courtesy of Fred Baldassarre)

Only a year after the Japanese entered Manila, the once so beautiful city was only a shell of its old self; the streets were dirty and full of holes; only an occasional automobile was to be seen; thousands of unemployed listlessly walked the streets, many of them in rags; small peddlers, offering all kinds of odds and ends for sale, crowded the sidewalks; there were thousands of beggars. Many of the shops had been turned into cafes and saloons for the Japanese soldiers. Downtown and in the best residence sections as well, whole blocks of houses and apartments were now brothels.

As the war continued on thru 1944, food was getting increasingly hard to find. Unlike the American forces that brought arms and food to the battle zones, the Japanese forces relied on resources from the occupied countries; everything was confiscated: autos, gas, food, and the Filipino’s basic staple, rice. Manila’s Mayor Guinto “asked” people to refrain from eating meat at least 3 or 4 days a week. As food grew scarce, the prices skyrocketed. Charcoal was selling for ₱8 ($4) a sack, a spoonful of sugar cost 20 centavos, and rice, now only available on the black market, was selling for ₱70 a sack. Although I can’t imagine the hotel’s chefs had much of a problem provisioning their kitchens with the high priority status for the army and navy officers and guests.

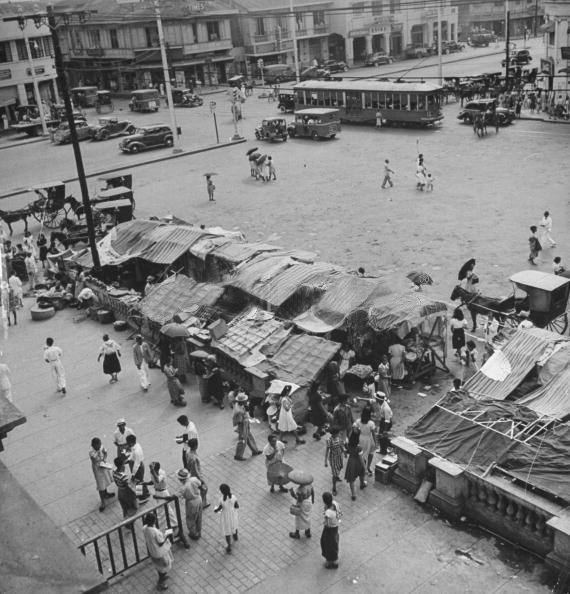

Vendor stalls by Quiapo Church.

Dr. Victor Buencamino relates, “The Japanese have no sense of humor. I was at a party at the Manila Hotel. Seated beside me was a Japanese major. A Japanese civilian, who has been in the States, introduced a hostess to me in joking terms: “Dr. Buencamino, I would like you to meet this young girl. She is thin because the price of rice is exorbitant.” Some Filipinos present got the joke and laughed. I did too. But the Japanese major got sore. He looked at the Japanese civilian angrily and said very tersely “After office hours, no talkee business. Understand?“ The Japanese civilian bowed respectfully and apologized. Must remember to give him my condolence, the poor man!” [Philippine Diary Project]

Practically devoid of private cars, Meralco Tranvias were the only transportation available during the occupation. – Rizal Avenue, 1943

“Mickey Mouse” money

“It was commonplace to see bayongs (bags) full of money at the market, although food was scarce enough toward the end of the war that it didn’t matter how much money one had. Japanese occupation money became worthless; people calling it “Mickey Mouse” money.” [A Child in the Midst of Battle, Evelyn Berg Empie]

Liberation

During the Battle for the liberation of Manila, the Japanese selected the Manila Hotel as one of their final stands. The hotel had been bombed once in September 1944 by Allied bombers when they were greeted by machine-gun fire from the roof. A section of the wing of the hotel on the bayside was destroyed. When the Allied forces converged on the hotel, the scene became a bitter floor-to-floor, room-to-room fight. It was then the hotel was set on fire by the Japanese.

The Japanese Type 10 120mm Anti-Aircraft gun was still present in the front lawn when the photo was taken in 1947 . (Source: Cito Maramba-Manila Nostalgia)

General MacArthur remarked, “I watched with indescribable feelings, the destruction of my fine military library, my souvenirs, my personal belongings of a lifetime. It was not a pleasant moment.”

The Manila Hotel now a burnt-out shell. – 1945

When the Battle of Manila was over, Jean MacArthur pleaded with the general to take her to their Manila Hotel penthouse hoping to find something of all the beautiful things and personal mementos they left there but all they found was five inches of deep ashes. A bomb had been placed inside their grand piano and detonated, setting the penthouse on fire.

Manila Hotel after the Battle of Manila.

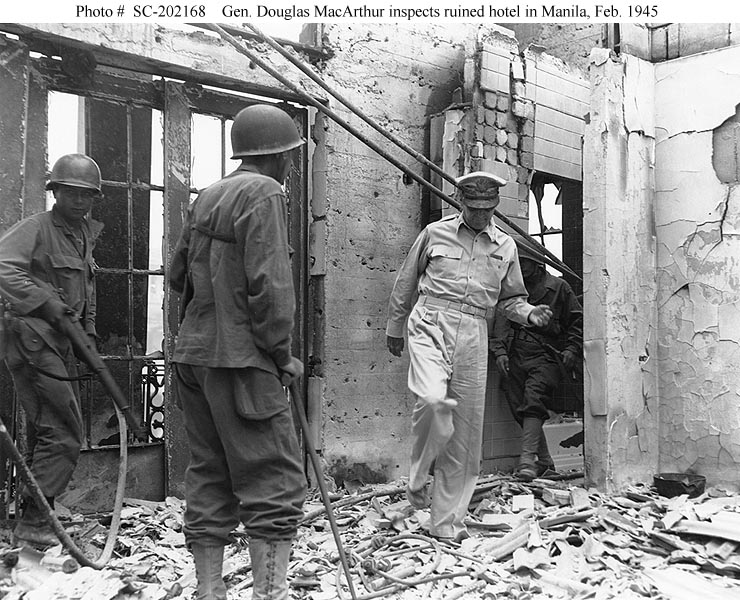

MacArthur visits Manila Hotel ruins Feb 1945

Nothing remained of the glory that was once the showcase of Manila but the spirit of the hotel as well as the Filipino people struggled to survive and it did.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur died in 1964, his wife Jean died in 2000. Both are interred at the MacArthur Memorial in Norfolk, Virginia.

Reconstruction and The Fifties

Former President Quezon’s aide, Col. Manuel Nieto was appointed to manage the cleanup and initial restoration. Damages to the hotel amounted to ₱3M but the Board was only awarded a million for repairs. The actual work which took over two years exceeded ₱10M. Within two months, most of the debris had been cleared and some public rooms were available even though evidence of shellfire was present throughout. The annex was closed indefinitely but the hotel reopened with one wing of rooms offered at a premium.

The first social event scheduled after the war was a Fil-American ball given to raise funds for rebuilding the city of Manila. It was a much needed morale booster for the city. The atmosphere was glittering and gay. People were anxious to put the last three years behind them.

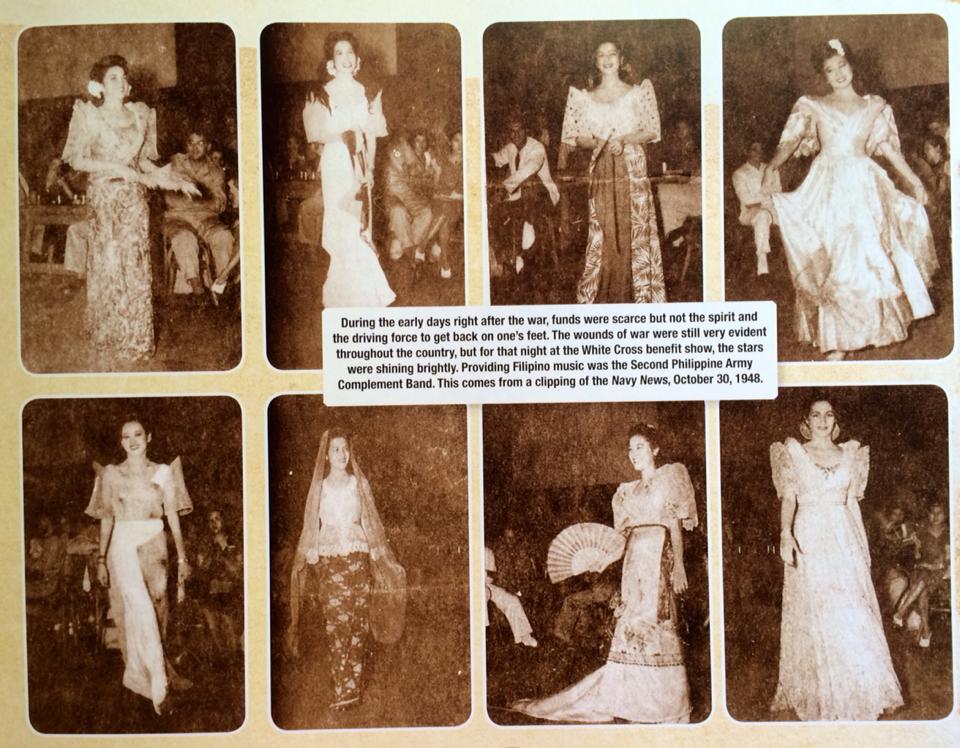

The White Cross Benefit Fashion Show in 1948 (Photo courtesy of Isidra Reyes)

Completely restored, the Manila Hotel glistened once again – 1948

Manila Hotel entrance-1950s (Source: AGSL Archives)

Money flowed freely from reconstruction funds, corruption was rampant (as usual) and the Grande Dame was losing its splendor and sheen and even more debilitating, it was plagued by theft, pilferage and political exploitation. Politicos didn’t think it necessary to pay their bills and guests stole the silverware. The government-managed Manila Hotel corporation was mired in debt and inevitable bankruptcy. It was decided to offer the hotel out to lease and eventual purchase.

Fortunately, the Bayview Hotel Corporation with Mrs. Cielito Zamora as Executive VP and Manager, picked up the lease in 1954 but not without a small problem. Employees laid off due to the lease were to be granted a separate gratuity. Tirso Cruz and his orchestra members sued as they were not provided the same benefit. They lost in court having been named as individual contractors and not employees of the Manila Hotel. I guess their swansong fell a little flat.

The Manila Hotel -1965 (Photo courtesy of Capt. Ed)

The hotel was still an epicenter of social life, adapting to new styles such as the disco fashions of the 1960-1970s.

Manila Hotel Champagne Room disco 1960s (Photo courtesy of Isidra Reyes)

Now in the mid-1970s, the hotel faced stiff competition from newer hotels being built in the Makati area where the business district had moved. The hotel was badly in need of updating and major re-design; there was talk of tearing the Manila Hotel down rebuilding anew. Architect Leandro “Lindy” Locsin was commissioned for the renovation. He led the way to save the original building and still created a 600-room modern hotel. The old hotel’s bayside annex was torn down. 149 rooms in the original building were remodeled into 100 modern rooms plus the addition of an 18-story tower behind the old building. Inauguration of the “new” Manila Hotel was on September 29, 1980 with Imelda Marcos together with Manila Hotel’s Roman A. Cruz Jr. celebrating its opening.

Leandro Locsin

Maynila Restaurant

Of course the Manila Hotel has gone through iterations of management and ownership over the later years but this is where my tour of the hotel ends. It still holds a very historic and warm part for everyone, not only in the Philippines but worldwide as an icon of Filipino hospitality.

I dearly hope it doesn’t go the way of so many heritage buildings in Manila that we’ve lost in recent years.

Balikbayan 2004

Upon our return to Manila and as we registered at the hotel, I was in awe of the grand lobby with its high ceiling and chandelier lamps. It was as I had remembered back in the day. At times there would be a small combo playing gypsy jazz or old standards. My imagination would take me back to when this building hosted famous actors, politicians, and even a general who would return to save this country from the Japanese. Here are a few photos I took while on our visit to the hotel in 2004:

My research for this article was derived from my personal library and many online sources but I relied most heavily on Beth Day Romulo’s book “The Manila Hotel”, a wonderfully detailed history of the hotel.

Republished with permission from the author. To read the original: http://www.lougopal.com/manila/?p=3330

Lou Gopal's father was an East Indian, his mother a Spanish mestiza from a long line of Zaragozas. He was born in Manila, and raised at the American School, so he feels quite multi-cultural. He's a retired Boeing software engineer living in Seattle with his wife, 4 sons and 3 grandchildren.

More articles from Lou Gopal