Leader of the Band

/An addendum to “A D.C. Springtime Concert in Manila” by Titchie Carandang-Tiongson

The Philippine Constabulary Band played at the 1909 inauguration of President William Howard Taft. (Source: U.S. Library of Congress)

But his principal achievement -- one might even say, his unstinting passion -- was organizing the Philippine Constabulary Band in 1902 and overseeing its continued recognition until 1940. Loving’s mastery of Spanish and Tagalog must have accounted for his unparalleled success in forming a band that would go on to win numerous awards and accolades the world over for years to come.

Loving’s tenure with the Philippine Constabulary Band was not to be continuous though. It was interrupted by World War I, a bout with tuberculosis, and an investigation into the racial conditions of African American soldiers and their mistreatment by white and non-commissioned officers.

Walter Loving in U.S. Army during the 1890s (Source; Wikipedia)

Loving blasted the widespread discriminatory practices of the Army’s white officer corps, noting that “African American soldiers were best treated and most effectively integrated into military units when white officers from the western United States and northeastern United States held command. Thus he recommended to the Army that white officers from the southern United States not be permitted to lead units with black soldiers.” "The assignment of white noncommissioned officers to colored units is a new departure in the history of the American army. Even in Civil War days colored units carried colored noncommissioned officers ... that most of these white noncommissioned officers view themselves in the light of the overseer of antebellum (slavery) days is shown by their practice of carrying revolvers when they take details of men out to work."

Ironically, according to research by William Jordan (2001), Loving later conducted an underground investigation of alleged “subversive activities by African American leaders, attending meetings and rallies in plainclothes and developing a network of informants. In one of his reports he would assert that African American socialists were "the most radical of all radicals" as well as allege "vicious and well-financed propaganda" campaigns run in black newspapers as being the impetus for the Chicago race riot of 1919.” But actually, these activists were fighting for equality in the same spirit Loving was blowing the whistle on racial inequality within the military.

After World War I ended, Loving returned to the Philippines to resume leadership of the Philippine Constabulary Band for another three years, after which he and his wife Edith retired to Oakland, California where the couple established a successful real estate business. Given still-persistent racial hostility in some neighborhoods, Loving would play the role as his wife’s black chauffeur while his light complexioned African American wife would “pass for white” when dealing with potential Caucasian buyers.

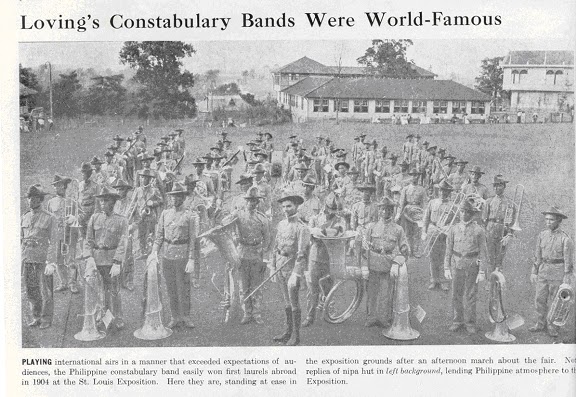

The Philippine Constabulary Band at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair (Source: http://adenu1980.blogspot.com/)

Later, at the invitation of President Manuel L. Quezon, Loving returned to the Philippines to helm the now-renamed Philippine Constabulary Orchestra from 1937-1940, and was commissioned in the Philippine Commonwealth Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel and also made "Special Advisor to the President of the Philippines." Loving later retired in Manila, and with the advent of the Japanese Occupation, became a UST prisoner of war until 1943 when the Japanese command released him for health reasons to a kind of gilded cage at the Manila Hotel.

There are conflicting accounts of how Col. Walter Loving died, but one thing all of the accounts agree on: Loving died at the hands of the Japanese in the closing hours of the war in 1945. The account most credible to this writer is the one which involved an encounter between Loving and General Yamashita (the general was not mentioned in Robert Yoder’s account, only “Japanese soldiers” who probably knew neither English nor Tagalog) at the entrance of the Manila Hotel. The general demanded Loving go with him, but Loving adamantly refused. According to Yoder (2013), with Manila's defenses on the verge of collapse to the advancing American and Filipino armies, the hotel prisoners were ordered to run to the beach while Japanese soldiers shot at them. The then 73-year-old Loving refused to run, declaring "I am an American. If I must die, I'll die like an American," whereupon he was beheaded.

Walter Loving, Director, Philippine Constabulary Band (Source: "Negro Musicians and their Music" by Maud Cuney-Hare, The Associated Publishers, Inc., Washington, D. C., 1936, University of Pennsylvania Digital Library)

In a 2010 article, a Philippine newspaper columnist contends, however, the Manila Hotel prisoners attempted escape and Loving used his body to barricade a staircase to prevent Japanese troops from pursuit; he was bayoneted to death in the process. A third account relayed in a 1945 Associated Negro Press story says that Loving was shot in the back by retreating Japanese troops. Mortally wounded, he crawled from the Manila Hotel to the battered bandstand at Luneta Park, the site of many of the Philippine Constabulary Band's performances, and died.

In 1952, Loving was posthumously awarded the Presidential Merit Medal by the Government of the Philippines during a ceremony at Luneta during which his final composition, Beloved Philippines, was performed. Loving was also the recipient of the Distinguished Conduct Star, the second-highest military honor of the Philippines.

The major source for this article was Wikipedia.

Collis H. Davis, an African-American independent filmmaker retired in Manila, has just completed a 95-minute historical documentary, “Headhunting William Jones.” He was video-director with Richie Quirino on “Pinoy Jazz: The Story of Jazz in the Philippines.” www.okara.com.

E-mail: chdavisjr@pldtdsl.net .