Kumander Liwayway: A Feminine Warrior

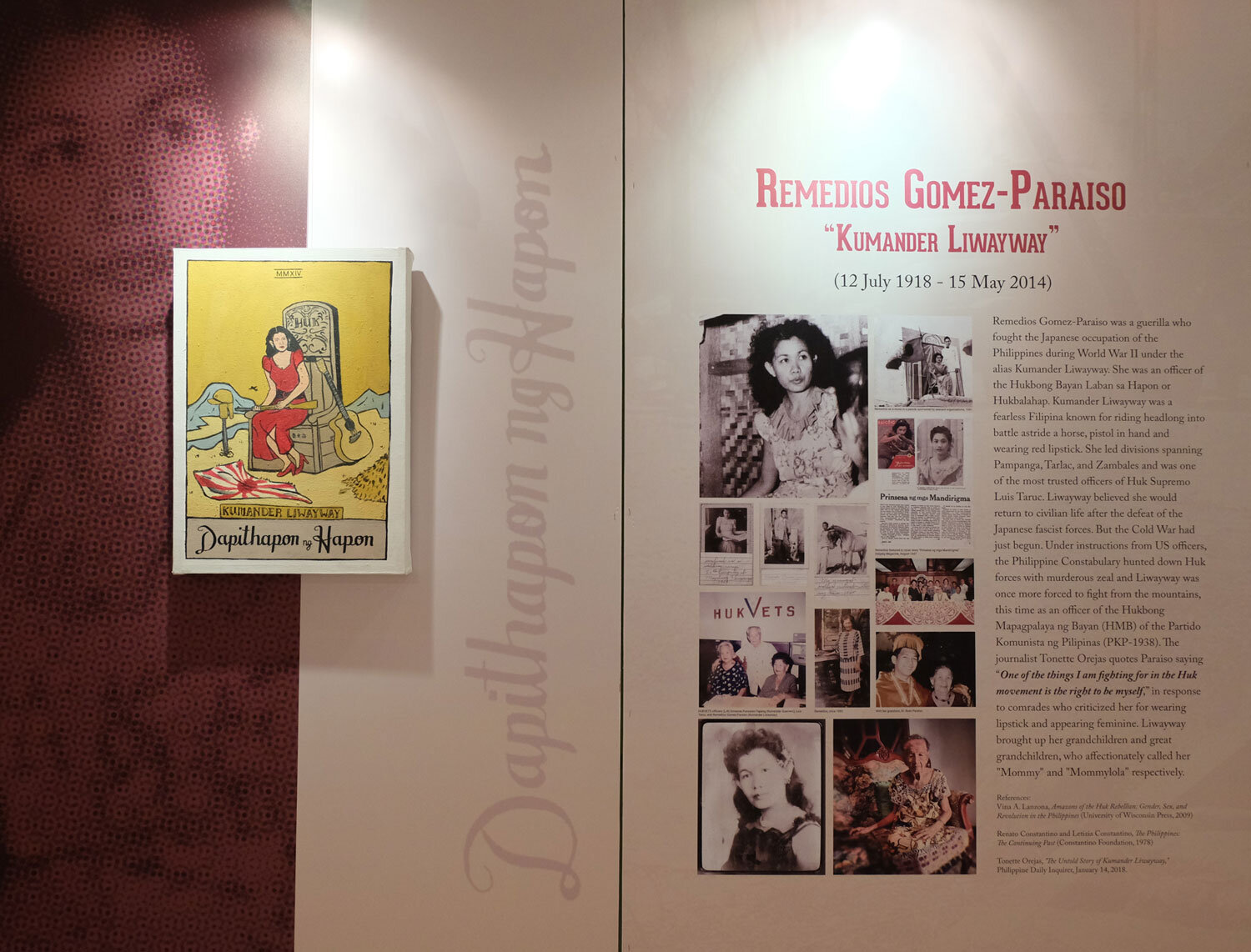

/The Kumander Liwayway exhibit. Photo by (c) AC Dimatatac/ICSC. Poster art by Johnny Guarin.

But what baffled her captors and the media was the image of this pretty, graceful, young woman who defied all notions of what a Huk guerrilla fighter, let alone a commander, was expected to look like. Liwayway became the subject of intense curiosity. As interviews and articles covered her capture and confinement, she began to be referred to as a Huk Amazon, like other Huk women guerrillas who fell into government hands. And the more they dug into her background and military exploits, the more fascinated media and the public became with this enigma of a Huk Amazon who was both feared and adulated for her beauty and calm composure; for indeed she was a favorite town beauty queen before she joined the Hukbalahap during World War II.

Remedios Gomez was born in Mexico, Pampanga, to Basilio Gomez and Maximiana Guinto, the second of eight children. In the 1930s most families in the province lived and worked on lands owned by big landowners under oppressive conditions. Central Luzon then was the stronghold of militant peasant struggles. Although the Gomez family owned a parcel of land, Basilio was a peasant leader who sympathized with the plight of the peasants and was elected mayor of their town.

The young Remedios was exposed to these peasant activities. She learned to ride a horse. In those days when carabaos were more prevalent, it was quite an unusual sight to behold a young maiden so gracefully riding a horse. She became a popular local beauty queen. Reaching high school, she helped support the family by selling rice and sewing dresses.

When the Japanese military units entered Mexico, Pampanga in 1942, Basilio Gomez, who was then the vice-mayor, refused to cooperate with the “foreign invaders.” He was arrested, tortured, and paraded around town as a warning to the people, and eventually killed. The Japanese soldiers refused to return his body to the family.

Remedios Gomez Paraiso aka Kumander Liwayway (Source: Google Arts and Culture)

The family left Pampanga and moved to Tarlac. By that time, the resistance movement called Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon or Hukbalahap had been formed. Filled with an intense desire to avenge her father’s death, Remedios was an easy recruit. Besides, there were reports that the Japanese were abducting and raping women. Strong-willed, Remedios could not be dissuaded from joining the resistance.

According to the family, Remedios’ mother appealed to Oscar, the sibling next to Remedios, “Your sister is a woman, I cannot stop her. So, can you accompany her and look after her?” Remedios joined the guerrilla unit of Eusebio Aquino (Kumander Biyong), under the general command of Luis Taruc.

She was called “Liwayway” (meaning dawn) and first assigned to the medical team to care for the wounded and the sick. All new recruits underwent training in guerrilla warfare: how to fight, handle weapons, stage an ambush, how to retreat, etc. As the resistance forces grew and additional units were formed, Liwayway who impressed her commander and comrades with her dedication, discipline, and seriousness of purpose, i.e., to avenge her father’s death, was given a squadron to lead.

Kumander Liwayway’s squadron harassed and ambushed the Japanese troops, raided their garrisons and garnered more weapons and ammunition. They engaged in skirmishes with Japanese soldiers and stopped them from further intruding into the area. Additionally, she was given the task of procuring food and supplies for the guerrillas and to serve as liaison between the Hukbalahap leadership and the barrio supporters.

Kumander Liwayway proved her mettle in combat. With two other squadrons, her unit engaged a large Japanese military force in the “Battle of Kamansi.” It was a fierce battle and there was no sign of let-up. Kumander Biyong (Eusebio Aquino) of one squadron ordered a retreat and the other squadron followed suit. But Kumander Liwayway and her comrades stayed on and fought the Japanese military force. In the end, it was the Japanese enemy who retreated.

She became famous after this encounter and her fame spread throughout Tarlac and Pampanga. The name Kumander Liwayway struck fear among the Japanese army. At times carrying a .50 caliber machine gun or a .45 caliber pistol, Liwayway and her unit would enter a town occupied by the Japanese enemy, and she would issue a stern warning for the enemy troops to leave the area, as well to inform them that the Hukbalahap guerrillas were just nearby.

“At times carrying a .50 caliber machine gun or a .45 caliber pistol, Liwayway and her unit would enter a town occupied by the Japanese enemy, and she would issue a stern warning for the enemy troops to leave the area”

Liwayway might have been a fierce commander and merciless towards the enemy, but she was merciful and generous to the people. She exacted discipline among the guerrillas under her command, which reached around 200 men at one point, but was said to be solicitous of their welfare. A well-known story about Kumander Liwayway that continues to be repeated to this day is how this woman warrior would always be well-groomed with polished nails, and would put on perfume and red lipstick before going to battle.

Liwayway herself explained that this ritual in fact gave her comrades greater confidence seeing their commander “fearless and calm.” At other times, she was supposed to have said that she wanted to look her best in case she died or was captured after a battle. But Luis Taruc said that Liwayway once told him, “I am also fighting for the right to be myself.” Liwayway is said to have always been posturyosa -- well-groomed with makeup until her death in 2014.

According to her family, Liwayway finally tracked down the Japanese officer who killed her father. She found and cornered him, and got her revenge. When asked what she did [to the officer], she simply said, “What he did to my father, what he did to us.”

Other stories have emerged, perhaps fusing fact and legend. Once, she rode on horseback to attend a meeting of guerrilla commanders. As she was passing through a barrio along the way, she was warned about the presence of Japanese troops there. She turned around and rode swiftly away for hours as far as possible until she reached the squadron under Kumander Katapatan. The latter seeing Liwayway, breathless and panting, made a nasty macho joke, “In case they [the Japanese] catch up with you, just lie down, anyway you are pretty, just lie down.” This so enraged Liwayway, who at the time was armed with her señorita and a .38 calibre pistol, she challenged Katapatan to a draw. She could not be appeased, even as the other guerrilla comrades tried to restrain her, and this went on for some time before she calmed down.

When the American military forces under General Douglas MacArthur returned, fierce fighting ensued to clear the Philippine territory of the Japanese imperial army. Supporting the land forces were U.S. military planes that dropped bombs on Japanese lairs to flush out the enemy. One such plane was shot down near where Kumander Liwayway and her guerrilla fighters were operating. They rushed to the area, found the plane, rescued the American pilot, and nursed him back to health until he was ready to leave. The pilot officer’s name was Bob (Robert) Tanner, who sought her out after the war. They became friends and continued to correspond with each other until the end.

With the surrender of the Japanese imperial army in 1945, the Hukbalahap guerrillas were ordered to lay down their arms. Some did, but others were skeptical because the U.S. military authorities began to hunt down the Huk guerrillas as communists. The Hukbalahap guerrillas had become the military arm of the merged Socialist Party of Pedro Abad Santos and the Lava-led Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP).

Poster art by Johnny Guarin.

In the general elections of 1946 held to form the new so-called independent Philippine government, the Nacionalista Party-Democratic Alliance coalition (NP-DA) fielded eight well-known Huk leaders and sympathizers, including Luis Taruc and Jesus Lava, as congressional candidates. They all won. They were, however, unseated by the new government under President Manual Roxas and Congress, who were heavily influenced by the anti-communist policy of the U.S. The Cold War era had begun.

The Hukbalahap guerrillas were the most effective resistance army during World War II and succeeded in preventing the Japanese military enemy from establishing control over Central Luzon. Yet they were denied full recognition, unlike other guerrilla units, and instead were hounded and arrested. Bitter and dejected over the turn of events, the Huk guerrillas went back to the hills, dug up the arms they had buried, and the Hukbalahap was transformed into the Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan (HMB), and a full-blown rebellion began.

Tragedy befell Oscar, Liwayway’s brother, around this time. Oscar, who himself had led a squadron against the Japanese enemy as Kumander Osing, was the regional head of the Democratic Alliance in Central Luzon. His unit was ambushed and Oscar was killed. Like many other Huk guerrillas who would have wanted to return to peace and civilian life, Liwayway and her comrades felt they had no choice but to resume fighting to protect their families and supporters, to continue the struggle for the peasants’ cause and “genuine freedom.” Still assigned to Tarlac and Pampanga, she underwent further political and military training, and led and trained a unit of rebel fighters.

Then in 1947 Kumander Liwayway was captured and became an instant media celebrity. Liwayway, like other Huk women warriors, “elicited awe and inspiration as well as fear and hostility.” She was imprisoned and tried for rebellion. She was brought to Malacanang and had the famous “confrontation” with President Manuel Roxas, who accused her of terrorizing people and attempting to overthrow the government.

In defense, Liwayway replied, “No, Mr. President, you are wrong. . . . We are only fighting for a decent livelihood and. . . democratic treatment in our plight. . . . Ninety-five percent [of Huks] are families of peasants, so I cannot see any reason why the Huks will terrorize their own families or why the parents will be afraid of their own children. We, the Huks, champion the rights of the peasants.”

She was released after a year upon issuance of a writ of habeas corpus, and the case against her was dismissed when the court declared that she was arrested and detained without preliminary investigation. Liwayway immediately rejoined her HMB comrades.

In 1948, Kumander Liwayway was married to Banaag Paraiso, a second cousin of the Lavas, a rich land-owning family of Bulacan. By that time, tensions had developed between Luis Taruc and his supporters and the Lava leadership of the PKP. Liwayway had met Paraiso, Kumander Bani, previously. In a meeting of Huk leaders and members, both Liwayway and Banaag found themselves the subject of discussions. Courtships and marriages were part of the life in the forest. Liwayway was the beautiful and daring Kumander Liwayway, identified with the camp of Luis Taruc while Paraiso was the handsome young man and cousin of the Lavas. What better way to try and resolve conflicts than a union of the best warriors from the two factions! Banaag and Liwayway were married apparently on that same occasion under Huk rites. (Their names “seeing the rays of light” and “dawn” found symbolic meaning in their union). Liwayway later admitted that while she had not chosen him, "she found the perfect husband and comrade in Paraiso.”

The union bore a son, Oscar, named after Liwayway’s fallen brother. Paraiso was sent to Iloilo as part of the expansion force in the Visayas. Liwayway joined him and while for the most part she assumed the role of wife and mother, she also helped set up and manage a political and military school for new recruits.

The rebel camp was betrayed by a close friend of Paraiso, Fred Gloria, and was raided by a unit of the Philippine Constabulary. According to the family, Liwayway had suspicions about Gloria who had arrived a day earlier and was seen to be wearing a pair of Keds rubber shoes. At the time no one could afford a pair of Keds among the guerrillas. Paraiso was killed during the assault. Liwayway’s instinct was to run, but not without her two-year-old son Oscar. She found him hugging a post while bullets flew over his head. Liwayway grabbed the boy and tried to escape but was captured.

Liwaryway was once again put in prison and allowed later to have her son join her in detention. Upon her release, she and Oscar stayed with relatives and friends, still fearful for their security. She then decided to live a civilian life with her son because she did not want her only child to grow up in the mountains, hiding and constantly fearful for their lives. When things seemed to be more settled, a sister who had landed a permanent job helped them get a housing unit in Project 4. Liwayway, a resourceful woman, started selling vegetables, later acquiring first a market stall and later more stalls which she rented out. She supported herself and raised her son and his education until he finished his engineering degree.

When Oscar later married and left with his wife, Lydia, to work in the Middle East, they left two young sons with Liwayway. The boys learned to call her Mommy. As they were growing up, she would talk about her past adventures as a guerrilla fighter. Whereas other youngsters were told fairy tales or other stories before they were put to bed, the two apos would be regaled with the battles she fought and of her comrades in the revolutionary movement.

Her stories and accounts were always so colorful and exciting. Liwayway was an enthralling storyteller. One of her grandkids said that the stories were better than the movies because their imagination would be fired up and the details became more real as they imagined them. They knew the descriptions of the Huk comrades so well that they would recognize them when some of them would come to the house, sometimes to stay for a day or two.

Liwayway continued helping her comrades. She served in the Executive Committee of the Huk Veterans Organization with Luis Taruc and worked for them to receive pensions as veterans of the Second World War. She continued to harbor those who were still on the run, or give money or rice whenever needed.

Remedios Gomez Paraiso, alias Kumander Liwayway, died in 2014 at 93 years old. She lived an extraordinary life that broke the conventional notions of women’s role in society. She proved as competent as men in leading a guerrilla combat unit and retained her femininity in the process.

To end, I would like to quote from the book Amazons of the Huk Rebellion by Vina A. Lanzona:

“. . . The Huk movement redefined [women’s] sense of place in Philippine society and history. In recruiting women to the revolutionary movement, the Huks broke new ground, challenging the division between the personal and the political and making sexual and familial relationships a central part of the political and social debate inside the organization. While women sometimes felt ignored or undervalued, the experience and political education they acquired transformed their sense of identity and their vision of transforming Philippine society. Haltingly and imperfectly, the Huks instituted what was just the beginning of a sexual and gender revolution that remain unfinished to this day.”

The stories of Oryang, Apolonia, Kumander Liwayway, Lorena and Gloria need to be told and retold, over and over. Our women heroes lived during important periods in our history. Their stories are part of the collective memory of our nation. Moreover, these were women who in different ways blazed the trail for the liberation and emancipation of women.

The essay was first delivered by the writer at the November 25, 2019 opening of the Alas ng Bayan exhibit organized by the Constantino Foundation, the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities, and 350.org Pilipinas. It will be published by the Constantino Foundation in a forthcoming collection of essays on progressive pedagogy, history, the humanities, and climate change.

Ana Maria Nemenzo, national coordinator of WomanHealth Philippines, share about the story of Commander Liwayway during the opening of the "Alas ng Bayan" an art exhibit featuring the paintings of five Filipina heroines who resisted national oppression, social injustice, and false gender narratives across different junctures of Philippine history here at UP Diliman Asian Center, Novemer 25, 2019. Alas ng Bayan is jointly organized by ICSC, the Constantino Foundation, and 350 Pilipinas.

(L-R) Oscar Paraiso, Ana Maria Nemenzo and Renato Constantino Jr. cut the ribbon during the opening of the "Alas ng Bayan" an art exhibit featuring the paintings of five Filipina heroines who resisted national oppression, social injustice, and false gender narratives across different junctures of Philippine history here at UP Diliman Asian Center, Novemer 25, 2019. Alas ng Bayan is jointly organized by ICSC, the Constantino Foundation, and 350 Pilipinas.

Opening of the "Alas ng Bayan" an art exhibit featuring the paintings of five Filipina heroines who resisted national oppression, social injustice, and false gender narratives across different junctures of Philippine history here at UP Diliman Asian Center, Novemer 25, 2019. Alas ng Bayan is jointly organized by ICSC, the Constantino Foundation, and 350 Pilipinas.

Sources

Interview. Ryan Paraiso, White Plains, Quezon City, September 2019.

Interview. Oscar Paraiso. Filinvest II, Quezon City, September 2019

Lanzona, Vina A. Amazons of the Huk Rebellion: Gender, Sex and Revolution in the Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2010.

Ana Maria "Princess" Ronquillo-Nemenzo is a socio-political activist and feminist, and a pioneer advocate for women's reproductive rights in the Philippines. She is a founder and National Coordinator of Woman Health Philippines, which promotes women's rights to reproductive self-determination and empowerment, health and development.