Justin Jones – Black, Filipino, Civil Rights Activist

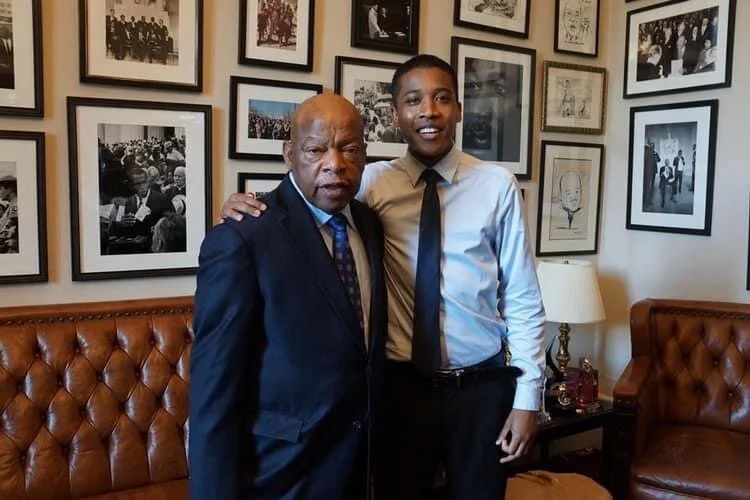

/Justin and Congressman John Lewis, while interning in Washington DC, 2016

Two years later, Justin is sitting at my dining table, and I can tell that he has indeed rediscovered his Filipino roots and honors them deeply. He tells me: “My Filipina Lola Tessie and my Black Lola Harriet are my first divinity teachers, first theology teachers, first spirituality teachers. I realize now that the family stories they told me about their childhood in the Philippines and in Chicago and San Francisco carried their indigenous roots.”

Justin and author Leny Mendoza Strobel

Justin grew up in Oakland/East Bay. As a biracial person who looks more Black than Filipino, Black became his default identity. Although he was raised by both his Filipina and Black grandmothers and being raised on collard greens, black eyed peas, and adobo, and stories from both sides of his family, Justin said that there was still silence about his indigenous Filipino grandfather who is Aeta. Outside of the home, the Black and brown communities in the East Bay made him aware that he is always perceived as a Black person. His hunger to get to know his Filipino identity always loomed in his young mind.

Justin playing in the water around age 5.

He became politicized in middle and high schools, and events such as the murder of Oscar Grant and Trayvon Martin motivated him to organize and become an activist. His English teacher inspired him to not be complicit with injustice; to speak up and stand up. Environmental issues, social justice and civil rights became central to his passions and concerns. He was a key organizer of Bay Area protests after Trayvon Martin’s murder. He remembers: “Some people were concerned that violence might erupt because of people’s anger, but the opposite happened. Protest was a place for collective grief, to lament, to be in community, express righteous indignation at what happened.”

Justin took his Filipino lola to her first protest in San Francisco against the Keystone XL pipeline. He now recalls that perhaps his passion for activism came from hearing of his lola’s stories about the People Power protests in the Philippines, and particularly about the Catholic nuns who kneeled in front of tanks with rosaries to stop them from running over those protesting against the Marcos regime. He also heard stories of the civil rights movement and the inhumanity of Jim Crow segregation from his Grandma Harriett.

After high school, Justin went to Fisk University, a historically Black university, where his role models, John Lewis and Diane Nash, had also studied. At Fisk, he received the John R. Lewis Scholarship for Social Activism. As a political science major, he continued to immerse himself in local civil rights issues in Nashville and became active in organizing work on campus and in the larger community. One of his memorable experiences is visiting John Lewis in his office. He said: “I waited for 20 minutes outside his office and when he finally invited me (in), I saw that it was lined with photographs of the civil rights era and he walked me through the history of the civil rights era. I heard that he always makes time to talk to young people and I’ve been inspired by him so deeply.”

Justin has been in Nashville, Tennessee for eight years now. After graduating from Fisk, he enrolled in a master’s program in Divinity Studies at Vanderbilt University. He continues to lead organizing efforts and when the George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests erupted around the country, Justin and other local activists occupied the Ida B. Wells Plaza in Nashville, and called for accountability and reckoning with institutionalized racism and police brutality. One of the focal points of the protests was the demand to remove the bust of Nathaniel Bedford Forrest, a KKK grand wizard, at the Tennessee state capitol. The 62-day protest led to 14 charges against Justin and, to date, 12 of those charges have been dismissed.

Justin in Washington DC at Black Lives Matter Plaza 2020.

Justin outside the Tennessee Capitol, where he helped to organize and lead 62-day occupation in response to the police murder of George Floyd.

Sitting around my dining table, Justin speaks of the intense trauma that activists experience when being out in the streets protesting, getting harassed and intimidated by police. Recognizing their collective trauma, he organized a retreat to tend to their pain. He told his fellow activists that they are warriors and healers. How are we healers, a few friends asked him. He told them that in his Filipino culture, there are babaylans who are both warriors and healers. He told them stories about his Filipino grandmother’s practice of honoring ancestors; how she would make the Sign of the Cross herself every time she passed a church; how she would say “Bahala Na!” as her expression of faith and trust in the Sacred. He tells me: “Ate Leny, the more I study decolonization, the more I realize that my Ibanag grandmother has always carried the indigenous culture within herself.”

Justin carries the prayers of his ancestors as he walks the path of making good trouble. In Nashville, he is carried by the Elders of the Civil Rights era, and he honors them with respect and care. Diane Nash has been mentoring and supporting him, and his gratitude to this beloved civil rights leader is profound.

Sitting with Justin and watching him walk his talk with courage and dignity inspires me. I feel his giftedness and I see it coming from his deep dive into the decolonization process and his reverent approach towards the calling of his Indigenous Soul. I see the Babaylan spirit in him.

Postscript: I recorded an hour-long interview with Justin but only 17 minutes of it were audible. I have been in many situations where the Sacred doesn’t want to be recorded. I smile and I bow my head.

Leny Mendoza Strobel is Founding Elder at the Center for Babaylan Studies and Professor Emerita in American Multicultural Studies at Sonoma State University. Find more info here: https://www.lenystrobel.com/

More articles from Leny Mendoza Strobel