Journal of the Vague Years

/Cover photo of the book, The Diary of Lilian Velez, from a publicity photo of LVN Pictures’ Enkantado (1948) showing Lilian Velez with her new leading man, Jaime De la Rosa.

Book Review: The Diary of Lilian Velez, Chronicle of a Star and a New Nation, 1944-1948.

Archivo 1984 and Arc Lico International Services, Pasay City and Quezon City, 2022

Today, she is little known and remembered; her brilliance as a comet on the silver screen was tragically snuffed out at age 24 by her fellow actor and co-star Narding Anzures in 1948.

Her name and memory might have gone forever into oblivion had not her daughter, Vivian Climaco Ocampo, supported by the co-publishers, Archivo 1984 and Arc Lico International, and the able team of Isidra Reyes, Renz Spangler, John Brian de Asis and Gerard Lico, persisted in putting into publication her personal diary of the years 1946 and 1948. Vivian did not even see the product of her efforts as she herself passed away in 2021.

Lilian Velez with one year-old baby Vivian (Source: Vivian Climaco Ocampo Collection)

Lilian’s artistic and musical pedigree were impeccable. Born in 1924, her father Manuel P. Velez was a renowned composer while her mother Concepcion Cananea was a popular zarzuela performer known as the Cebuana Nightingale. On her paternal side, Lilian was a descendant of Filipino painter Damian Domingo. Lilian’s father, Manuel, apart from being a renowned composer, was also a successful bandleader, music teacher, music publisher and movie director.

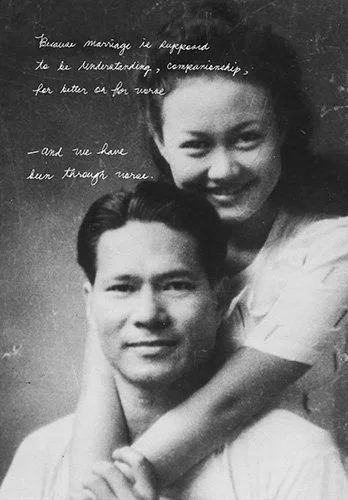

Her equally gifted polymath husband, Jose Climaco, was a composer, music director, band leader, actor, stage director and Hollywood-trained film director. Together, they had a child Vivian, born in 1944, who would be the bearer of her memories and legacy.

Such a silver-spoon-in-mouth origin might have resulted in a spoiled movie brat, but it is clear from her diary, which begins on January 1, 1946, that the lovely Lilian was not only supremely talented, but she was also driven, highly disciplined and work-oriented as well as being compassionate, kind and generous. But that is getting ahead of the story, which is inspirational but ultimately, tragic, and filled with the irony of what-might-have been.

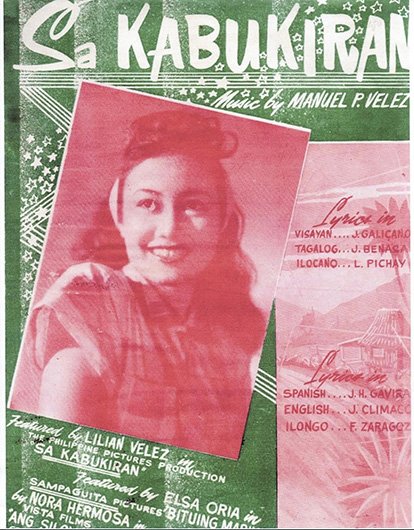

Before the war, Lilian had already made her debut as both singer and actress. In 1938 she won first prize in a contest of KZRM-Radio Manila when she sang her own father’s composition Sa Kabukiran, which remains popular to this day. In 1941, having already done two successful films produced by Filippine Films, Lilian was then matched with former child star Bernardo “Narding” Anzures in Binibiro Lamang Kita, a light comedy directed by Carlos Vander Tolosa.

Lilian Velez as a fetching barrio lass in Balintawak and salakot in a publicity photo for Jose Climaco’s Sa Kabukiran (1947) (Source: Vivian Climaco Ocampo Collection)

The war put an abrupt pause to this path to stardom and, like the rest of the country, Lilian and her now husband Jose Climaco would endure the draconian rule of the Japanese from 1942 to 1945. Her most anguishing experience was her husband’s imprisonment and torture at the hands of the Kempeitai.

A loving portrait of Lilian Velez and her husband, Jose Climaco, with an excerpt from Lilian’s diary (Source: Vivian Climaco Ocampo Collection)

With the country in tatters, little was left for actors to do but to hitch their wagon to the American star, which meant entertaining the Yankee troops who now (re)occupied the country. This they called “the Liberation.” Lilian Velez and her husband, Jose Climaco, were among those handpicked for this new fulsome duty of the “Special Service.” This meant developing a repertory of songs, dances and drama snippets for new American audiences from among the ranks of those assigned to the Philippines. This little-covered part of entertainment history is amply featured by Lilian, with such venues as the Rizal Memorial Stadium, the Cielito Lindo nightclub (with a swimming pool all its own), the Roosevelt Club, the Manila Jai Alai, the Wack Wack Golf and Country Club, Fort McKinley and various U.S. Army and Navy facilities.

An important sub-chapter in this part of the diary is the overwhelming expectation of the Filipinos for the coming Independence Day, scheduled for July 4, 1946. In this, Lilian is out of sync with her countrymen, as she supported “Dominion status” (or continued Commonwealth status, like Guam or Puerto Rico) for the Philippines.

With utter disdain for the Spanish and revulsion towards the Japanese, Lilian had nothing but blind admiration for all things American, shown in her love of American film, culture, food and language. As entertainers, Lilian and her husband were later replaced by new American imports, but not even this seems to have dimmed her Americanophilia. It is appropriate that her first film with leading man Serafin Garcia was entitled G.I. Fever.

The diary gives us insights into Lilian’s interior life as well as her perennial balancing act between aspiring screen star and domesticated wife and mother. She notes that she would often begin each day with Mass and Holy Communion, which she once failed to do as she had forgotten to fast several hours before as was then required. With none of the easy credit and big money now available to celebrities, she and her “hubby” Joe (as she called him) scrimped and saved to build a house on Pulog Street in Sta. Mesa Heights. She would take public transportation and delight in such mundane treats as a movie in nearby theaters and ice cream and snacks at the popular restaurants of downtown Manila. She balks at her husband’s thrifty ways and delights in being a modern partner in supporting their child, whom she adores and grooms to enter her profession.

Indeed, it is an intriguing depiction of personal and social history and also a reflection of women’s roles and dilemmas of the day.

We are not privy to what might have been taking place in her interaction with the glittering movie world, now led by such formidable personalities as Doña Narcisa (Sisang) de Leon, grandmother of director Mike de Leon. Doña Sisang had even recruited her to co-star with Jaime de la Rosa as lead, replacing Narding Anzures, who had been her partner in previous films. This is arguably one possible reason for what drove Anzures to kill Lilian.

Colorized photo of Lilian Velez and Narding Anzures on the set of Fermin Barva's Ang Estudyante (1947) (Source: Lito Ligon Collection)

What led Anzures to take such a drastic step remains a mystery. Was it an Othello-like jealousy toward the modern Desdemona’s new co-star de la Rosa, or toward Lilian’s own husband Jose Climaco? Had Anzures mistaken his screen romance with Velez for reality? What was in the missing diary entries from mid-September 1946 to December 1947, the time she was shooting G.I. Fever (1946) and her last two movies with Narding Anzures? What could have inspired Anzures to destroy his own future as well as that of Velez in a mad act that was later to be described as “temporary insanity,” which accounts for his escaping the death penalty and even earning a Presidential pardon before his own death and release from prison?

The diary leads to other questions that remain open to this day. The fact that it ends two days before her murder adds a note of pathos to this journal.

An important postscript is the life of daughter, Vivian, and her father Joe Climaco after Lillian’s terrible death. Vivian was the last to see her alive and the four-year-old witness in court who identified her mother’s assailant. Her father saw to it that she would not follow in her mother’s footsteps. Vivian (no relation whatsoever to another film star with her mother’s surname) went to St. Theresa’s College, became a schoolteacher in Japan and a well-loved English teacher in Xavier School Greenhills, a far cry from her mother’s career. She credited her faith in God and her profession with having sustained her throughout her life.

Banner headline article of The Manila Times, 28 June 1948 entitled “Lilian’s Child Tells of Mother’s Death.” featuring an account of the court testimony of Lilian’s daughter, Vivian, one of two eyewitnesses of her mother’s murder in the hands of Narding Anzures (Source: Architect Gerard Lico Collection)

Joe Climaco subsequently remarried, had other children and pursued a successful career with professional ties to Don J. Amado Araneta as musical director of Araneta Coliseum and to Doña Sisang de Leon as director of several LVN Pictures films.

It may be of some consolation to her loved ones that through this book, Lilian Velez’s memory has been resurrected; her 100th birth anniversary on March 3, 2024 should be celebrated by Filipino cinephiles. Only recently was her tomb at the Manila North Cemetery rehabilitated.

“The Diary of Lilian Velez” is packed with not only facts, but also with first-rate pictures and movie stills of the era. Splendidly edited and designed by the Arc Lico International team and with Ms. Isidra Reyes’ masterful introduction and annotation, it is a handy Baedecker to the turbulent years of our country’s early independence. This we owe to the bright, beautiful and doomed Ms. Lilian Velez.

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He is now engaged in writing, traveling and is dedicated to cultural heritage projects.

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.