Into the Unknown: The Strange Skulls of Banton, Romblon

/Hike to the Guyangan Cave System with AFS 2023 (Photo by the author, July 2023)

Banton, where the Guyangan Cave System is found, is the northernmost island of Romblon Province. With a total land area just over 30 km², it is about 1/24th of New York City. But despite its small size, Banton has a significant role in telling us more about our country’s rich history.

Our intrepid tour guides were none other than Kuya Giovanie Fabro and Sir Abner Faminiano, two of the staunchest advocates for Bantoanon culture and heritage. With their help, we braved our way to the vaunted Guyangan Cave System, a large network of caves where rich archaeological finds have been uncovered.

After about a 30-minute hike (it definitely feels much longer when you’re holding your breath all the way up), we finally reached Silak Cave. It’s the most visited part of the Guyangan Cave System due to its relatively safer route and incredible archaeological finds.

Silak Cave is not so much a cave as a cove. Only about 10 people could go in at a time because of the limited space. To get inside, you would have to sit down and shimmy downwards through a tight opening. As soon as I (the last one in the group) landed, I was greeted by a collection of skulls and ceramics all piled on a slab. Beyond that, the cave opened up to a view of the ocean below. This orientation towards the sea can be seen in many burial caves throughout the country, which is why some theorize Silak Cave to have once been a burial place for ancient Bantoanons.

Visitors in Silak Cave with Giovanie Fabro (right) (Photo from Guyangan Tour PH Facebook Page, December 2023)

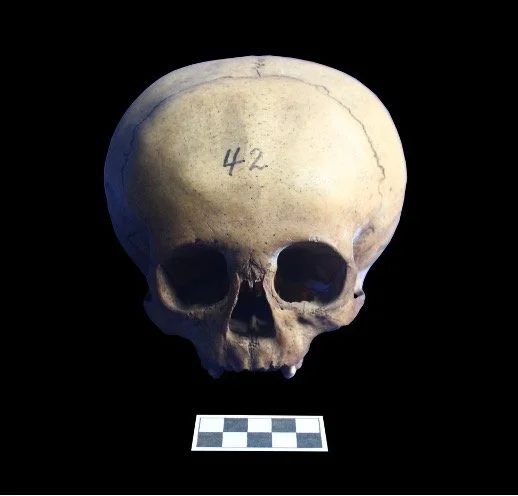

Several coffins and skeletal remains have been excavated here since 1966. In 2013, the Guyangan Cave System was even designated as an Important Cultural Property by the National Museum. Despite these recognitions, the story behind these skulls still remains largely unknown. After all, these are not just regular skulls – many of them had been cranially modified to make the foreheads much higher than regular.

These specimens have been studied by Medrana (2005, as cited in Paz, 2009), identifying two kinds of cranial modifications: 1) fronto-verticooccipital -- the frontal bone and occipital regions are flattened; 2) fronto-parietooccipital -- the frontal, parietal, and occipital bones are flattened, resulting in the lateral enlargement of the skull.

Example of cranially modified skull found in Banton (Photo from the National Museum of the Philippines Facebook Page, 2020)

The exact dates of these burials are still unknown, but researchers posit them at sometime between the 4th and 13th centuries (Evangelista, 1966 as cited in Paz, 2009). This is largely based on the associated goods found with the burials: Sung, Yuan, and Ming China wares as well as a couple of Sawankhalok and Sukhotai Thai shards.

But the question remains; why were these skulls modified in the first place?

The true answer remains to be seen, but some researchers have theories. One is that this practice was done only among the elite. It would make sense, given the fact that many of these modified remains were buried alongside extravagant goods. Besides the imported pottery mentioned above, there were also turtle shell and wooden combs, carnelian beads, shell bracelets, and gold earrings.

While cranial modification is a gendered practice in some parts of the world, as in other Visayan groups, the same could not be said for the ones found in Banton. Both male and female specimens were found on-site. Researchers also posit that cranial modification must have been done during infancy, when the cranial vault sutures were not yet completely fused.

New road to Silak Cave (Photo from Guyangan Tour PH Facebook Page, November 2023)

Back in July 2023, the road to the Guyangan Cave System was still very precarious. It was unpaved, with no ropes or railings to hold on to. This is partly the reason why not that many locals visit the cave system themselves. Fortunately, the National Museum has been planning to fix the routes to the cave system to bring these heritage treasures closer to visitors.

According to Kuya Giovanie, however, the perceived dangers are just part of the problem. Many locals do not visit the caves because they view it as a sacred place. While no oral tradition regarding the caves remain, Bantoanons still recognize the deep history of the place. They fear that going too often to the caves would disturb resident spirits.

Nevertheless, Kuya Giovanie hopes that the caves would be studied even more. Aside from the Silak Cave, there are other caves in the system that are also home to burial sites. Who knows? Perhaps more archaeological and anthropological research would eventually unravel the mystery surrounding these skulls.

“Para sa akin, ang mga bungo na ito ang magsisilbing libro namin (For me, these skulls would serve as books for our community),” Kuya Giovanie tells me over Facebook Messenger in February 2024, emphasizing how important these finds are to uncovering more about Banton’s – and the Philippines’ – past. “Isa talaga ito sa dapat ipagmalaki ng bawat Bantoanon, kung gaano kayaman ang aming kultura at ang buong cave system (This is really one of the things every Bantoanon should be proud of -- the richness of our culture and the entire cave system).”

Indeed, much remains to be discovered about the Guyangan Cave System. Though Banton is a small island about 10 hours away from the capital, it could tell us significantly more about our pre-colonial past. Despite archaeology’s colonial roots, today it actually holds great potential for decolonizing our past. Learning more about our country’s history is an inherently powerful act that subverts wrong assumptions about our past. The Philippines had a rich and thriving culture long before any European has set foot in our land.

Reference:

Paz, M. (2009). Cranial vault modification practice among the early inhabitants of Banton Island, Romblon: An anthropological perspective [MA Thesis]. University of the Philippines Diliman.

Aidrielle Raymundo is currently finishing her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Anthropology from the University of the Philippines, Diliman. She is also a freelance writer with experience in writing about Philippine culture, history, pop culture, and more. Her research interests include anthropology of development, engaged anthropology, identity-building, and audio-visual methodologies.