Hiking Heaven: The Magic of Japan’s Kumano Kodo

/The Japan Kumano Kodo, is the equivalent to the Way of St. James or the Spanish Camino de Santiago. The Komano Kodo was recognized by UNESCO in 1992. Along with the Camino de Compostela, inscribed in 1985, they are the only two World Heritage Pilgrimage Routes recognized by UNESCO for its conservation and preservation programs.

The Komano Kodo is a network of mountain trails that converge at sacred temple centers in Southern Osaka, connecting the sacred temple centers in Hongu, Hayatama, and Nachi along the Kii Peninsula. Some trails are moderately challenging. Others call for some mountaineering skills. Pilgrims who complete both Camino and the Kumano Kodo earn a Dual Compostela. Having earned a Camino Compostela, our goal was to earn the Dual Pilgrim certificate, a program that Spain and Japan instituted in 2015. To earn that, we had to hike at least three shrines that converged at the Hongu Taisha shrine center, or at least cover 100 km. The Hongu shrine is Kumano’s equivalent to Santiago de Compostela. Pilgrims who have not completed at least three shrine visits in the circuit are issued certificates here. We completed Takijiri, Chikatsuyu, and Hoshimon trails. We felt it was well earned. We are among the first 5,000 who have earned it.

Showing our Dual Pilgrim Certificate

Patricia and I had been training for this hike, aiming for distance and elevation to the level that our senior years could sustain. We thought we were ready. In 2022, we walked the 170 miles from Portugal to Spain along the Portuguese Camino. The relatively flat terrain did not pose real challenges. But due to the pouring rain in the last week of the Camino, we each caught a cold, and after we returned to San Francisco, COVID. It made the walk less pleasant, albeit still very remarkable; but we were grateful for the experience. The Komano Kodo was all mountains, seven peaks to be exact. There was no similar mountain terrain nearby. Our neighbors, seeing us walking in earnest in hiking garb and all, thought we were nuts. Another teased: “Do you enjoy pain?” We smiled and shrugged it off, determined to be healthy for this trek.

Here’s a thought: 100 meters corresponded to 25 floors. The elevation we were supposed to climb was between 600-800 meters. Do the math. It became all intention and effort. A Buddhist saying brings a comforting thought:七転び八起き “Stumbling seven times but standing up in eight.”

We learned much from our Camino experience. Unlike the Camino, where the popular trails developed from local practice into a pilgrimage industry, the Kumano Kodo was a recent addition to the pilgrimage trade, although the trails have existed for 1,000 years. Since 2004, the local government has supported an organized route infrastructure of signs (distance and emergency phone numbers), bus stops (for snacks), and restrooms with bidets! The planners left nothing to be desired. Signs in Kanji came with English translations. Like the Camino experience, we contracted our lodging and luggage transfers. Raw Travel, an Aussie company, handled this. They are necessary for managing luggage and lodging after a long hike. We could focus on the trail and save time that’s better used for exploring the destination and savoring our accomplishment. Thus, along the way, we beheld a view of Japan and its people in ways no ordinary tourists on trains and tour buses would have. Unlike the Camino de Santiago, Hollywood has not sullied the air of sanctity that still pervades in the Kumano and is respected by devotees. The “old” and the “new” appear to be in harmony. On the trail, you may pass the ruins of an old rest house, farm villages that grew persimmons and tea, or take a forest bath under the swaying canopy of towering cedar trees. When you reach the village for a stop, a vending machine is available to serve coffee and cream in warmed-up tins. Carry your trash with you, though. In this part of Japan, cleanliness — is godliness, not just next to it.

I once read, perhaps from Werner Hertzog that “The world reveals itself to those who travel,” especially to those who travel on foot, I would add. It couldn’t be truer while on the Komano.

The highlight of our trek was a temple stay. This was the clearest insight on Japan we could get in so short a time. It also prefaced our trek and set the tone for the rest of our journey.

The Sacred Center, Mt. Koya, Kii Peninsula

The train system in Japan is a bewildering maze of routes served by different railroads. The train rides from Kyoto to Osaka to get to Koyasan would have been nerve-racking were it not for the graciousness of fellow passengers. We only had the vaguest idea of how to make the transfer connection to Koya, but a lady in our carriage tried to help us by checking her smart phone. Our Nihongo was just as incomprehensible as her English. We understood enough that our connection was a local commuter train loop. Unbeknownst to us, there was an older gentleman listening in. When we got off the train, he signaled with his hand to follow him. In any other foreign country, I would’ve ignored it, but we trusted the people enough to set aside these suspicions. We followed the gentleman, swimming against the current of the morning commuters, and turned toward an escalator that led down to another platform. The gentleman stopped turned to us, pointed at the electronic train schedule, gave a thumbs-up, then disappeared in the throng of office workers before we could even utter “arigato” (thank you). On the Camino, this was a sign of “giving back.” We had many “give backs,” throughout the Kumano.

The local train from Osaka connected us to another local system that wound around the mountain side to take us to a cable train station. The funicular train was the most direct way to get to Koyasan. The piped-in voice boasted that it travels 1,000 meters in five minutes. Indeed, pine and cedar trees whizzed by as the train hurtled up the almost vertical tracks. Indeed, in five minutes, we reached the station to transfer to buses for a 10-minute drive to Mt. Koya village, the oldest sacred center and destination for the Koyasan.

The bus zigzagging along the mountain road, the scent of pine and cedar trees, and the cool air reminded me of old Baguio. The Muryako Temple, where we were to stay, was just a short distance from the Koya bus stop. We came inside a grand, well-weathered wooden gate. A river of white pebbles separated the driveway from the receiving office where a monk, identified by his gray kimono, attended to a computer. We asked if we could check in early, giving our names. He inspected the guest list. Then, with a serious look on his face and said, “So sorry, you are not on our guest list!”

Our expressions turned gloomy. We were excited about the temple arrangement. Patricia attempted to call Australia but got no response. Australians were on public holiday. Despair slowly crept in. We were tired. We had no alternative lodging. The temple confirmation was not double-checked by our travel agent. The head monk who had been summoned offered to let us stay at the lodge for ¥58,000 per night even though they were almost fully booked. Cash only, he added. How quickly the disappointment tired us. We stumbled upon a small restaurant and each had a bowl of noodles. Noodles do wonders for comfort. I remembered that the travel company had a presence on Facebook. I sent a complaint and an urgent note to whomever might read it, detailing the situation.

Soon enough, the Facebook Messenger pinged back. Adam, the person on the other end, apologized and instructed us to visit another temple, which was only five minutes away from the first one. We collected our luggage and thanked the monk for safeguarding them. We had put the temple in a tough spot since it cannot refuse anyone seeking shelter, Patricia later explained.

The Nan-In Temple, our new lodging was on a steep hill, but that was the least of our worries. The innkeeper greeted us warmly and instructed us to remove our shoes. He then offered us slippers while his assistant took a rug to wipe the road dirt from the luggage rollers, ensuring they wouldn’t damage the beautiful cedar floors. The assistant delicately rolled our luggage past three corners along the hallway and pointed out our room. We didn’t expect to be given an entire wing to ourselves. We were the only guests. One room is 4-tatami (a 3’x6’ rush grass/rice straw mat) as Japanese rooms typically are measured. We had two adjoining rooms with sliding oil-paper screen doors.

Stillness enveloped us as we basked in the gentle light from the oil-paper screen panels, delighted at the turn of events. One room was for tea and another for futon beddings. The cream-colored tatami and golden cedar walls gave a sweet aged scent and cast a soft golden glow in the room. In the hallway, I slid aside an oil-paper screen window. It opened to a view of a landscaped garden with an ancient gnarly cherry tree, a worn-out stone bench, and a mossy stone lantern in one corner. Just imagine the view after the first dusting of snow in December. Tranquility.

We skipped the onsen (steam bath) for now and dressed in yukata robes at hand to get ready for dinner that was served in the Buddhist manner. A young monk quietly knocked on our door and gestured for us to go to the dining room. The tea room was spacious; measuring about eight tatami mats, with only a central low table.

There were no other guests at dinner. The monk vanished into another room and reappeared with the first tray of dishes. We gasped. Dear reader, I’m sorry for not being able to share a picture, but take comfort in knowing that the presentation was heavenly. The meal presentation embodied Zen – empty, yet fulfilling, is the most I can say.

The highlight of our trek was a temple stay. This was the clearest insight on Japan we could get in so short a time. It also prefaced our trek and set the tone for the rest of our journey.

The Japanese Buddhist dinner, called Shojin Ryori was a vegetarian feast for the senses. Steamed rice (served last) and miso soup form the base. The young monk, who introduced himself to us as Yoshiro or “Yuko,” surrounded our dinner tray with a colorful array of small dishes featuring seasonal vegetables, tofu, and mountain plants. I recognized the soy beans. The small dishes came in different colors—red, green, yellow, white, dark brown, each highlighting sweet (potato), sour (plum), marinated daikon, and natural flavors that I barely could identity. The meal appeared sparse yet felt so balanced. Immediately, I become a convert. While we were enjoying dinner, they had made our futon beds -- fresh warm comforters and buckwheat pillows (felt like rock).

The loud clanging of temple bells, the call to morning prayers, awakened us at 6:30 a.m. Donning our yukata, we quickly shuffled in our slippers to the temple at the end of the hallway. Heavy incense smoke filled the air and made me instinctively grope my pockets for my rescue inhaler. The chief monk chanted from a book of sutras, ringing a small bell after each prayer. The chant tones and incense smoke were mesmerizing, even though the words made little sense. Shifting to the left, the monk approached a taiko drum and punctuated his chants with vigorous drumming. In 45 minutes, the ceremony came to a close. Yuko, the young monk, came to fetch us and brought us to the tea room for breakfast.

A vegetarian Japanese breakfast

A Japanese breakfast differs radically from what we call an American breakfast. With my iPhone, which I did not forget to bring this time, I went into vengeance photography mode. Yuko brought out our dishes in stages —miso soup first, followed by an attractive layout of small dishes of pickled vegetables, fermented red beans, a marinated vegetable that tasted like dried fish, and the rice. Like our dinner, the taste and colors harmonized perfectly. The servings seemed small, but they lasted us the entire day.

We spent the whole day visiting the grand shrine; marveling at the Zen rock garden, and observing centuries-old screen paintings and scrolls I had seen only in books while teaching Asian Civ.

The Zen rock garden at the grand shrine

At the temple grounds, while admiring the landscape, I saw an older gentleman stooping each time at the ground as if looking for something. Curious, I walked close to him. He stood up straight and offered me some pine needles. He had been picking pine needles—ones with needle leaves only. We gladly accepted them, thinking it to be a religious practice. He walked away and continued stooping at the ground. Intrigued, I quickly looked at the guidebook. Legend has it, in Koya’s origin story, its founding monk was led to the site by a three-footed crow, to a solitary pine tree that grew only three-leaf needles. We now began searching the ground for more of it. A foreign couple came up to us, puzzled at what we were doing. I handed him the three-leaf needles I found. “Here, I wish you peace and good luck!” The circle of blessings thus closed.

The highlight of this town walkabout was the visit to the Okunoin Cemetery, said to be the largest graveyard in Japan where founding Buddhists and Shinto monks and shoguns were buried. The historical marker said there were roughly 200,000 souls living there. There are no dead here according to Shingon Buddhism, just spirits waiting. The thought made us shiver, so we repeatedly said “tabi, tabi po” (may we respectfully pass by) so as not to intrude on their solitude.

Walking through the Okunoin Cemetery

The ambiance was eerie, yet peaceful. Some gravestones wore red cloth aprons and red woven yarn hats. Described in literature as “Jizo” stone figures and figurines, their purpose is to seek enlightenment for all creatures. Bibs on smaller figures safeguard a child’s soul that “left too soon” to be of service to their parents. Leaving the cemetery, I felt the weight of so many souls lifted off my shoulders. I was completely unaware that my favorite aunt’s final days were approaching. I was to hear, two days later.

"Jizo" stone figures

Dinner was not the same 18 dishes as the first night – sweet white beans, creamy jelly-like tofu, pickled vegetables, a persimmon filled with diced salad; and fall season soup of shiitake mushrooms, daikon, taro cubes, tofu – the most that I could identify. It was high-fiber, nutritious, and pleasurable to ensure a good night’s rest.

A second Japanese dinner

At the temple, like the morning before, heavy incense smoke cast a dim light in the room, but the crackling fire at the altar cast a glow on the monk who sat chanting prayers. A fire ceremony! Patricia had always wanted to experience one. The Muryoko Temple featured it, which is why she chose it as our first lodging choice. Tiny showers of cinders flew around, but they sputtered harmlessly as our temple abbot stoked the embers while chanting the sutras. The robust fire hissed and crackled but despite the intense heat, the blaze never grew taller. The chanting now sounded in stereo. The source of the second voice puzzled me. I turned to the right and saw a foreigner in monk’s garb intoning the same sutras in a deep, resonant voice. The fire, incense, bells, drums, and chanting transformed the room into a multisensory space.

After the prayers, the Abott greeted the pilgrims who had completed the Kumano and then offered blessings to those preparing to undertake the journey. On that auspicious note, Patricia and I checked out of the temple and hurried downhill to catch the bus to Kii Tanabe, where at Takijiri-Oji, the trailhead of Nakahechi, our own hike was to begin.

To reach at Takahara, our first stop from the trailhead was the Kirinosato Organic Inn, we had to hike from Takijiri 10 km inland, and upward, some 400 m. It was a relatively moderate climb with a gentle downhill. The trails were well marked and sign-posted. At each shrine we passed, on a trail, an oji -- small protective spirit houses – had little boxes with a stamp to mark your Kumano passport as proof of your visit.

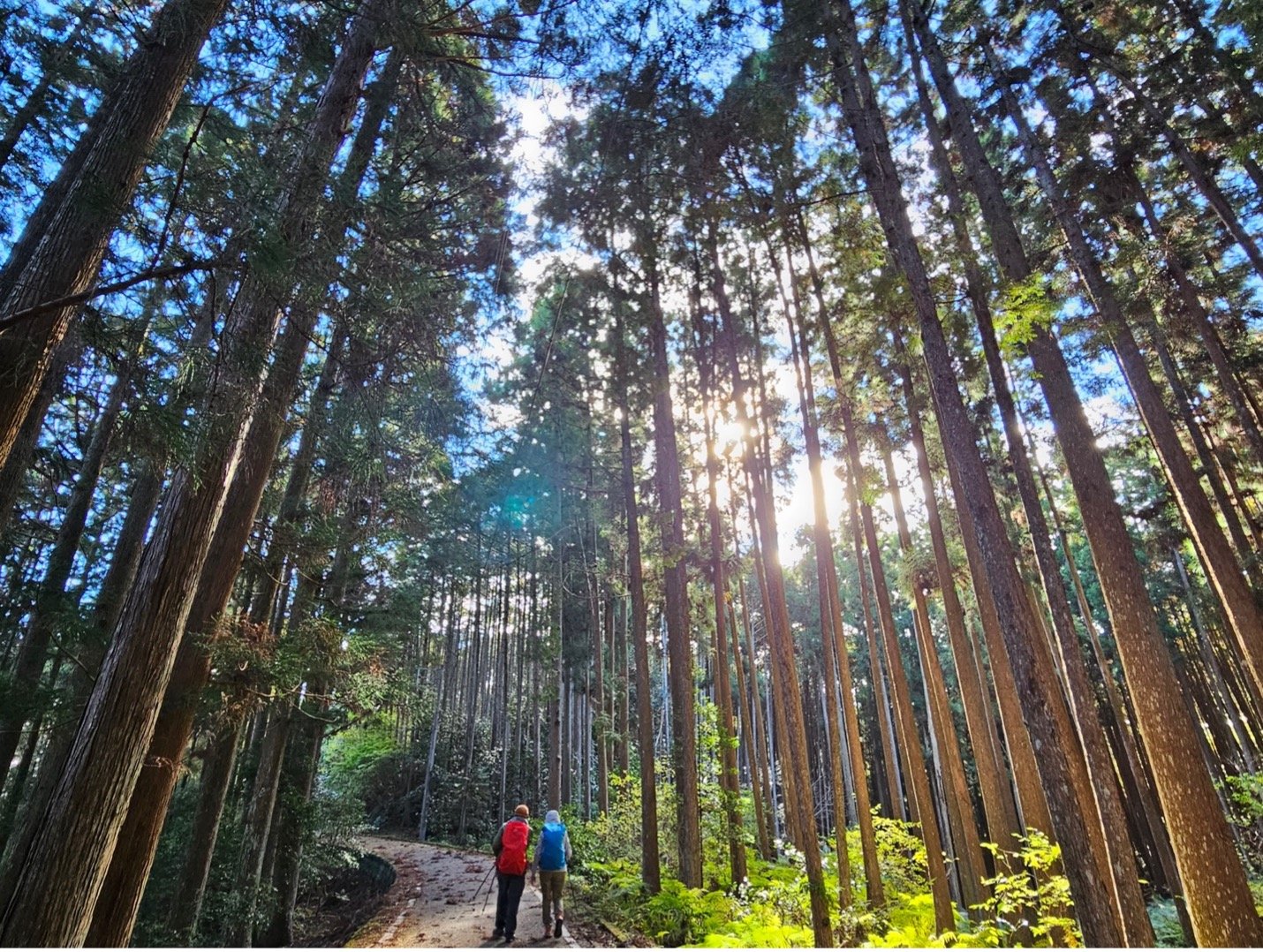

The way to Tanikahara was not difficult. There was a narrow crevice on the path, but we decided to bypass it because you had to unload your backpack to squeeze through it. We were now in deep forest of towering of cedar trees. They grew arrow-straight to incredible heights from the hillsides, and suffused the early morning air with cedar scents. The trail was a mix of stepping stones and leaf-covered soft earth. It was incredibly quiet. Not many people were on the trail. Midway, we rested and had lunchbox meals provided by hotel the night before. We had now grown to nine people -- four women, three men, all Aussies. We were together for five days of the hike and they proved to be much fun to be with.

With our Australian fellow pilgrims

After two hours and we arrived at a rest stop. I checked my watch, it read 400 m. We had climbed roughly 1,300 feet. After a brief rest, we plodded on to reach a ryosan at the edge of a ridge. The Kirinosato Organic Lodge is a true oddity in the pilgrimage route. It seemed to be in the middle of nowhere, but as we filed past the entrance we were greeted by flamenco guitar music! What? At a mountain top, in the middle of a pilgrimage route? After a long and tiring walk, the sound of flamenco, and the prospect of an espresso, advertised at the bar, was my vision of paradise. After checking into our rooms, I sat with an espresso at the patio overlooking the valley. The young lady who brought my espresso smiled and answered, “Yes, our Shoyu-sha (proprietor)” played the guitar. She nodded that we could make requests from him. I stared across the ridge at slivers of clouds floating along the hillsides like cotton candy. The sky was turning to dusk. Dawn would be spectacular, I thought.

A peaceful view at dusk

I took a quick dip at the relaxing onsen and dressed up for dinner. Our companions relaxed around the lobby, waiting for dinner. The owner, Jian, strode in with a guitar in hand. He gently handed it to me and said, please play. I peered at the guitar’s label – Jose Ramirez, 2003! My own guitar came from the same shop, decades older. I was in home ground. I quickly played through my practice repertoire. The guitar felt warm and relaxing to the hands after two hours of stomping about with my hiking poles. Our Aussie friends grabbed seats close by to hear the music better. They clapped enthusiastically after I finished. I handed the guitar to Jian. He crossed his legs and in true flamenco fashion, rapidly executed a toque airoso with rasgueados and golpes (finger roll and tapping). How strange is that? Right in heart of the Japanese Camino. At that instance, the two Caminos were one.

Walking through cedars

Dr. Michael M Gonzalez after decades of classroom teaching in Philippine and American colleges, retired in 2022. He is looking forward to devoting more time to his nonprofit activies with the Hinabi Project, the NVM & Narita Gonzalez Writers’ Workshop, the Kaisipan.org as an outreach to the culture and arts communities. Outside of that, he is an avid student of fiction and nonfiction writing; and the classic guitar, and indigenous music.

More articles from Michael Gonzalez