Her Mission Was in the Cards

/Poethig is a San Francisco Bay Area artist whose output is as versatile as it is prodigious. Aside from a long list of visual, video, sound and performance art exhibitions, she has completed dozens of major public art projects, received numerous grants including one from the National Endowment for the Arts, curated multiple innovative shows, all the while serving on the faculty of the Visual and Public Art department at California State University, Monterey Bay.

Curious as to why this tall, blonde, blue-eyed dynamo is so invested in Filipino culture, I caught up with Johanna as she installed her current show, Positional Vertigo at the Mercury 20 Gallery in Oakland. Did she identify as a Filipino American artist? I wanted to know.

Johanna Poethig spins a piece at the opening of the Positional Vertigo exhibition. Filipino American imagery is both overt and subtle in her work, as in the inclusion of the words “Gall Bladder” on the wheel (below numbers 15987). Poethig revealed that this refers to a Philippine tribe that gives equivalent importance and mythic status to that organ as we do to the heart. (Photo © France Viana)

“I can’t call myself a Filipino American artist as I’m not ethnically Filipino, Poethig reflects, “but I certainly think of myself as an American Filipino artist. The culture and concerns are very much a part of my art. I moved to the Philippines when I was four months old, my activist father and feminist mother were missionaries involved in urban industrial missions. My parents insisted that we integrate; they didn’t send us to American school. Growing up in Malate, I went to PWU and later JASMS. I didn’t move back to the US until after high school, so I really grew up Filipino.”

Public art projects are a large part of Poethig’s oeuvre, and she has completed dozens of commissioned murals including one on Lapu Lapu Street in SOMA, at the I-Hotel, public transport stations, a Cesar Chavez mural at Sonoma State University, and more, many with activist narratives that serve as intervention. The impetus came from street art, she recounts: “When we moved back to Chicago, I was very inspired by the street art of Bill (William) Walker. When I came to the Bay Area, I saw the beautiful murals in the Mission and wondered, why nothing Filipino? This motivated me to do the mural on Lapu Lapu Street in SOMA, and later a People Power mural on Alemany and more. Public art is its own animal and I confess that when I work on public art objects, I aim for content, not just design. I’m interested in the muralist tradition of narrative; I want to tell a story, to give meaning to the site. Collaborative, community-based art comes out of the feminist perspective and is the antithesis of the patriarchal one-person artist archetype. Also, large political pieces provide an antidote and challenge to Corporate America and I love to engage that theme where appropriate. Public art is a shared space and shouldn’t be dominated by corporate advertising. Just to have art instead of marketing in public spaces— I consider that to be a victory in itself.”

Poethig advocates for public art with a missionary zeal that distinguishes her professorial practice. “For over a decade I’ve taught a painting and mural class at CSU Monterey Bay because I really don’t buy into the common prejudice that one has to choose between being a studio artist and doing public or social art. I like building bridges between the two disciplines and offer my students the experience to do both.”

Songs for Women Living With War embodies much of the public art aesthetic: It towers as a memorial and is a collaborative work, employing many voices and stories to weave a tapestry that articulates activist aims. “I met M. Evelina Galang who received a Fulbright scholarship researching the WWII Japanese Occupation ‘comfort women’ from the Philippines,” Poethig shares her inspiration for the project. “Reading her book, to be published this year, LOLAS' HOUSE: Survivors of Wartime Rape Camps, I was moved to curate a living memorial. There are so many war memorials dedicated to men, how many to the women who suffered and struggled? Galang is an amazing and dedicated advocate, one of the most important Filipina American writers living today, and the stories she has collected deserve to be remembered.”

Bahay ni Lola by Johanna Poethig at the Songs of Women Living With War exhibition, Pro Arts, Oakland, 2016. Artworks graphically and viscerally narrate struggles and include a video of a “comfort woman” reacting to the newly installed plaque in Manila commemorating their WWII role during the Japanese occupation, conceptual pieces and sound art. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Colonization is a recurring subject in her art, and Poethig stretches its definition to include humorous and satirical critiques of consumerist capitalism, as in her 2015 show Glammorgedon. “There are many kinds of colonization. Besides historic colonization, we are colonized by advertising, by patriarchy, by many social constructs. Growing up in the Philippines in the ‘60s when many in the country were anti-American, protesting Vietnam and the like, I got to see the other side of colonization,” Poethig recalls, “and it has made me hyperaware of all types of oppression and suppression.”

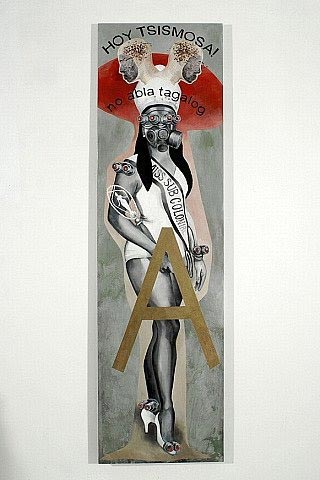

Poethig tackles a broad spectrum of topics in her works including technology, social issues and games, but many have familiar imagery from Philippine culture: babaylans, beauty queens, galleons and the obligatory balikbayan box. I ask her if she thought that seeing through an American-Filipino lens, through a veritable Coke bottle, influenced her art practice on a meta level.

“Yes, that balikbayan box is pretty much mandatory,” she laughs. “Much of my art, particularly the curatorial and public art projects, come from my being very social, which is partly my personality, but largely exhibiting a very Filipino trait—to be social and inclusive. I enjoy interacting with many types of people — seniors, youth, and that got me started organizing exhibits for them even if I didn’t think of them as curatorial projects at the time; I just wanted to give them a voice. It is also important to me to work through class structure, although that part may have come from my missionary upbringing. What is definitely a Filipino influence is the humor, the merciless teasing, that I like to incorporate in my art. We love to laugh at ourselves.”

Self-identified as an American Filipino artist, Poethig hybridizes imagery from both cultures as in Kayumanggi , above, from her 1996 Babaylan Barbie series. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Lola Remedios, quilt, at the Songs of Women Living With War exhibition, collection of M. Evelina Galang. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Poethig’s mural on Cesar Chavez at the Sonoma State University Information Center/ Library, features two Manongs, (detail). Stenciled in is the often-overlooked history that it was the Filipino workers of the United Farm Workers who first voted to strike on September 8, 1965. A Cesar Chavez historian that Poethig had consulted objected to this centerpiece and emailed her angrily. Over the years Poethig has received appreciative emails from Filipino American students who did not know of this hard fought history. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Poethig’s Filipino imagery includes beauty queens as this piece from her 2008 WASAK exhibition at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Poethig’s OFW Drowning, from the 2008 Galleon Trade: Bay Area Now 5 Exhibition. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Poethig’s current exhibition Positional Vertigo, features spinning wheels of fortune, interactive divination boards and a painting of technocrats attempting to escape bonds of electrical cords ala Houdini. “Positional Vertigo is about where are we today, about the confusion of things that come at us— at life, games and chance predictions. It is also about identity; how do we put all these signs together and make some sense of it? Who I am, growing up in the Philippines and here trying to integrate past, present and future? These wheels are a way of dealing with many signs and trying to integrate them into something meaningful,” she explains.

Wheel of X, from the current Positional Vertigo exhibit, includes a portrait of artist Eliza Barrios, with whom Poethig has collaborated since the 1990's in Filipino American artist collectives DIWA and Galleon Trade. (Photo © Johanna Poethig)

Noting the preponderance of chance and destiny themes in many of her series, I ask if she has had personal experiences with Philippine manghuhulas (fortunetellers). “One of the most uncanny experiences I had was as a college student, on my first trip back, I went to Iloilo where a friend gifted me with a psychic card reading,” Poethig recounts. “I didn’t have any idea of what I wanted to do then, I wasn’t an artist yet, and this psychic read my cards and said she saw me doing not only private art but art on a large public scale. It was truly prophetic. I am generally pragmatic but could not escape the mysticism that permeates Philippine culture. My current show celebrates this mystical side of my life.”

Positional Vertigo runs from January 5-February 11, 2017 at Mercury 20 Gallery, 475 25th St. Oakland, CA. Catch Johanna Poethig’s artist talk on February 3, 2017 from 6-8 pm at the gallery.

France Viana is a journalist, visual artist and marketing consultant. She is an active board member of Philippine International Aid and the Center for Asian American Media, sponsors of the CAAM Asian American Film Festival.

More articles from France Viana