Heneral Antonio Luna’s Railroad

/The Tutuban Centermall (Source; Wikimedia Commons)

After the shooting of Filipino sentries in San Juan on February 4, 1899, which triggered the Philippine-American War, the Americans quickly took Caloocan, a commercial center north of Manila and the Tutuban railroad depot in a few days despite a fierce defense by Luna’s army. As Commanding General of the Army of the Filipino Republic, under President Emilio Aguinaldo, Luna understood the strategic value of the railroad, which the Americans would put to good use throughout the conflict.

“In a country that showed little progress in 300 years of Spanish colonial rule, the railroad was a real vision of modern possibilities.”

Tutuban now is a shopping center. Before its gentrification, I spent many afternoons there poring through the archives of the PNR (Philippine National Railway. In 1888, the Spanish colonial administration built a rail line from there to Dagupan in Pangasinan with British and Scottish engineering expertise. Known as the Ferrocaril Manila à Dagupan, railroad construction was started in 1888 and completed in 1892. When it was finished, the railroad created a “commercial corridor” -- a length of territory that encouraged commerce from one end to the other, in this case, between Manila and Dagupan, passing through the provinces of Bulacan, Pampanga, and Tarlac. Pampanga and Bulacan in particular were the centers of upwardly mobile ilustrados, who were educated and modern even under colonial rule. The railroad immediately benefited these provinces whose towns produced the daily necessities for 19th century urban Manila and its suburbs. Before the railroad, rice, sugar, fowl, and fruits were carted on water buffalo-driven carromatas or shipped along the Bulacan and Guagua rivers on cascos -- large cargo barges that disgorged its goods along Manila’s Pasig River after several days of travel.

Tutuban today, the 168 Shopping Mall (Source: Project Pilipinas 2011)

In the Luna movie, the common folks, relatives and friends who wanted to experience the thrill of riding the now-requisitioned train, crowded out the General’s soldiers. Beyond the very Filipino trope of “makiki-angkas’’ to cadge a free ride through nepotism and “pakikisama” sharing, the railroad was a real, technological novelty that finally reached Philippines, the backwater of the fading Spanish empire. The enthusiasm for the train was real given that before the railroad, travelers in the Philippines lamented the condition of its roads:

Seis meses de polvo (Six months of dust

Seis meses de lodo Six months of mud

Seis meses de todo Six months of everything)

Official reports from the railroad archives housed at the old Tutuban station indicated that revenues from passenger fares were by far more than from freight. Foreign travelers in Manila at the time observed the natives’ obsession for riding the train. In a country that showed little progress in 300 years of Spanish colonial rule, the railroad was a real vision of modern possibilities. Where it took 27 hours to travel from Manila to Dagupan by steamer and three days by horse carriage (carromata), the ferrocaril took the wide-eyed indio passenger only eight hours to get to Dagupan.

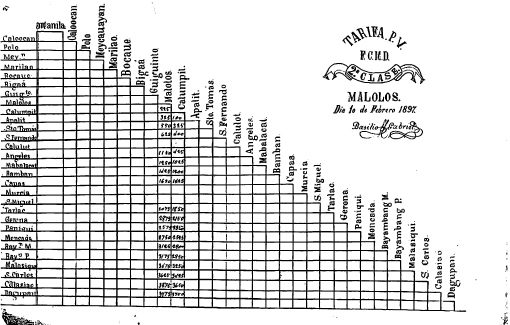

Train stations from Caloocan to Dagupan, 1897

Along the rail line, the train passed several stations where vendors of all sorts hawked their products--live chickens, sweets, boiled bananas, suman, or mangoes, to the train passengers, until they reached their final destination in Dagupan.

Even Jose Rizal, could not hold his curiosity for this new technology. Already well traveled, Rizal had seen and experienced modern conveniences in America and Europe and understood the impact of technology. It was even rumored that he and his engineer-friend Fernando Canon, played around with an electrically charged cane, which they would use to shock stray dogs. Naturally, Rizal was curious as to how this novel transportation could be of great importance to his project of reform and progress. But there was also a lingering angst in him because this new technology had dealt him a big blow.

Leonor Rivera, his sweetheart of 11 years, was from a prominent Dagupan family where the railroad terminated. Leonor's parents feared that their daughter’s association with Rizal, who by now was a notorious and marked person to the Spanish authorities, would endanger them. The mother embargoed all her letters to Rizal and Rizal's letters to Leonor. Rizal would later learn that Leonor had been betrothed and then married to Henry Kipping, an engineer of the railroad. Thus, Rizal wrote in 1891 to his friend Blumentritt, acknowledging the disruptive history of the railroad elsewhere, that “alas, the first blow of the railroad was to me."

While the tricolor flag raised by Emilio Aguinaldo at Kawit, Cavite in 1897 ushered the birth of a nation, the ferrocarril signaled the birth of the Malolos Republic in 1899. In the movie, “Heneral Luna,” there is a scene of the 19th century train speeding across the Luzon landscape. As the train rolls towards Malolos, Bulacan, the capital of the new Filipino Republic, the Filipino Revolutionary army stand in parade formation along the railroad tracks, awaiting the arrival of Aguinaldo’s inaugural train as it heads for the capital of the new Filipino republic. It must have been a splendid sight--the train was bedecked with tricolor and festooned with flowers. What could be a more fitting image that Aguinaldo and his cabinet perhaps imagined to symbolize a free and independent nation, a new nation with a railroad traveling toward a new future.

Soldiers at the Aguinaldo mansion (Photo courtesy of Arnold Dumindin http://www.filipinoamericanwar.com)

The moment of glory was short lived. Two months after the inauguration of the Filipino republic, U.S. soldiers fired on Filipino sentries. Thus began the Philippine American War. The US army quickly secured Caloocan and captured the Tutuban railroad depot. As commanding general of Aguinaldo’s army, Luna understood the military importance of the railroad. His strategy was to tear up the tracks to delay the train carrying US soldiers and munitions. Accustomed to rail technology and military logistics, the Americans were able to quickly restore rail service. Luna’s entrenchments were useless against Gatling machine guns mounted on train flatbeds. Unable to defend the towns along the railroad, Luna proposed guerrilla strategies to lure and extend American lines toward the northern mountains where they woud be more vulnerable. Beset by Aguinaldo's untrustworthy allies, the plan did not come to fruition. Luna’s Revolutionary army eventually collapsed and he himself was assassinated by soldiers loyal only to Aguinaldo. Once the U.S. army secured the railroad, it also secured the economic corridor from Manila to Dagupan.

After Aguinaldo's capture, American entrepreneurs restored the railroad, now renamed MRC -- the Manila Rail Co. It fell into the hands of British and American investors, including magnates J.P. Morgan, whose intent was to sell stocks as investment. The MRC hoped to attract capital by advertising a rail line to Baguio, the colonial summer capital. The efforts were puny to say the least and failed. During the dry season, rail ties along the river bed were laid from Dagupan to Camp One at the foot of the mountain. During the rainy season, the rail ties and sleepers were dismantled to avoid losing them to flood waters! In the end, under Governor General Harrison, the proponent of "Filipinization" (the idea that the Filipinos must learn how to govern themselves), transferred the management and its huge debt to the all-Filipino Assembly. Politicians and students objected to the transfer, calling the MRC as useless project that siphoned money from the gold reserves and away from more useful development projects like a national road system.

The MRC trudged along and was extended to reach Bicol but became the prize for political parties who lobbied for pork barrel and various concessions. In the end, modern roads and gasoline-fueled bus and motorcars became the predominant transport system. Until now, government administrations have failed to developed the railroad into a modern system or did not want to. For now, Filipinos in Manila will have to count their blessings that there is at least an MRT/LRT, and not forget that once in their history, a railroad played an important role in the pursuit of nationhood.

Dr. Michael Gonzalez has degrees in History, Anthropology, and Education. A professor at City College San Francisco, he teaches a popular course on Philippine History Thru Film. He also directs the NVM Gonzalez Writers' Workshop in California. http://nvmgonzalez.org/writersworkshop/index.html

More from Michael Gonzalez