Forget Them Not

/Most of the Filipinos who first settled in Santa Clara Valley in the 1920s and early ‘30s were Ilocanos. One of the last of them still alive is Esteban (“Steve”) Cabebe Catolico, a WWII veteran of the 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment who survived his older brother Mariano Cabebe Catolico (1909-2009).

Mariano, who immigrated in 1928, and Esteban were cousins of my stepfather Dalmacio (“Danny”) Laya Cabebe (1914-2008), whose first wife was my mother Mária (“Mary”) Vidal (Lapaz, Abra; 1907-1970). The three Pinoys were from Barangay Pantoc, Narvacan, Ilocos Sur, and remained close, life-long cohorts working for and retiring in the City of Palo Alto. They were active in the fraternal organization Caballeros de Dimas-Alang, Malvar Lodge No. 7, San Jose, California, and in the Pantoc Association.

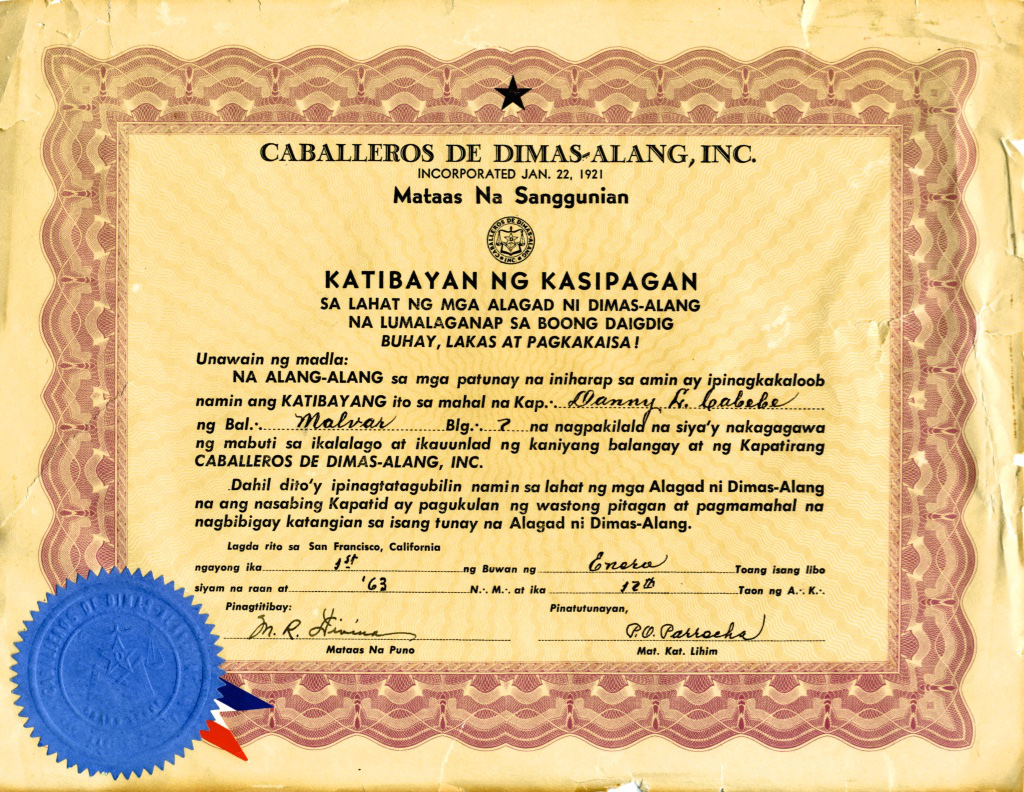

Certificate of achievement awarded to Danny L. Cabebe by the Caballeros de Dimas-Alang, honoring his contributions to the Malvar Lodge, January 1963 (Source: Alice Cabebe Guin collection)

Dan, who immigrated in 1930, passed away a few months short of 94 years of age, and Mariano 12 months later, missing 100 years by a little over a month. That left his brother Esteban now 103, as probably the last of the pre-Tydings-McDuffie Law (“The Philippine Independence Act” of 1934) immigrants who lived near or frequented the now-vanished “Pinoytown” enclave in San Jose’s old Chinatown.

However, the two Catolico brothers did leave a living legacy as they, along with other leading Filipinos in the early 1930s, founded the still functioning Filipino Community Center of Santa Clara County. Fortunately for later generations, the Catolico brothers with Frank Bravo, Leo Escalante, Sr., Alex Fabros, Sr., Val Ordonez, the Peralta brothers -- Max, Gene and Tony -- and Severino Ruste had the foresight in those years to lead the effort to raise the funds needed to purchase the land and build the Center.

At a Caballeros de Dimas-Alang ceremonial dinner in San Jose, California, late 1940s. (l-r) Esteban Catolico, Mariano Catolico wearing a Barong Tagalog, Mary Cabebe in her terno, and Danny Cabebe (Source: Ragsac family collection).

These three First Wave Ilocanos are a part of the “un-storied” generation as there was no organized effort to document their early life experiences. Fortunately, we were able to video-record, for our history project, the life stories of Mariano and Esteban in person. We also recorded the history of some of their deceased peers, including Dan, through their children, the Fil-Am “Generasian,” who are now in their 80s and often referred to today as the mánongs and mánangs.

Most of the Ilocanos I knew in the 1930s and ‘40s were employed as farm laborers or service sector workers who had only an elementary school, or maybe a junior high equivalent education -- 6th grade for my father Sergio (“Sharkey;” Pañgada, Santa Catalina, Ilocos Sur; 1907-1994), none for my mother (even with no formal education she could converse in Tagalog, Visayan and English, besides Ilocano). The three Pinoy boys were products of an educational system of the WWI era, less than two decades under American rule.

Mariano was unique not only for his longevity but also, in contrast to his town mates and friends, he wanted to go to a university and study for a degree. So he applied to and was accepted by the University of California, Berkeley, graduating in 1935 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in history. He went on to graduate school there to earn a Master of Arts degree in history in 1937. He was proud to be a U.C. alumnus, even though throughout his university years he had plenty of room in lecture halls for no white student would sit near him.

He was an unusual Pinoy, not only because of his struggles, degrees and longevity, but also for his sharp memory, being able to recall for our video interview details of Pantoc, family members, immigrating to and starting life in the USA, his town mates and friends, attending Cal, his Filipino U.C. classmates (all of whom returned to the Philippines), meeting his wife, Isabel, (Laur, Nueva Ecija), all the while naming dates, places and people. He proudly told us that all three of his children had college degrees, as did his wife (Manila Central University, 1951). Mariano was content and happy with how his life played out, with no regrets for living as a Filipino in the U.S., except for one, the same probably for others with a university education in the 1930s who were not white.

Mariano’s dream was to teach history, the subject he loved, but he could not get a teaching position or even work in an office, supposedly because he was not a U.S. citizen but, he suspected, because he was brown. Even with his master’s degree and, like so many other Filipino men of that era, he work variously as a houseboy, cook, farm laborer and even as a contractor of other Filipino laborers. For us Filipino Americans who went to college, we fortunately did not have to endure that kind of rejection, although that doesn’t mean there is no discrimination in our academic, working and everyday lives. Mariano was a pioneer in that respect, but probably wasn’t recognized as such then or given a tribute for his accomplishments.

“Mariano was unique not only for his longevity but also, in contrast to his town mates and friends, he wanted to go to a university and study for a degree.”

For all those First Wave Pinoys, I made one small personal, private effort.

When Dan passed away, his wife, Editha (Laoag, Ilocos Norte), asked me to give the eulogy on behalf of her, his daughter Alice Joan and his grandchildren, Erik Regala, Treven Regala and Lisha Guin, and great grandchildren. I made up a short eulogy, and having given tributes before for my family -- my father Sergio (it was just too difficult to do one for my mother), brother Ruben, Uncle Benrabe Reg Ragsac and his wife, Aunty Mary Quenga, and Uncle Frank Rapadas Ragasa, and for my Fil-Am friends of many years, Dixon Campos, Rudy Calica, Harold “Hal” Canion, Matt DeGuzman, Paul Lagasca, and Rudy Tenio -- I accepted her request.

Lakay Danny (we called each other “lakay”) was one of the last of my father’s “Mánong Generation” who had passed away years earlier and, in reflection, I felt he and his generation should be remembered. The only thing I could think of at the time was to give the eulogy as if I were talking directly to Lakay Danny, but speaking in Ilocano, so that it would represent in a spiritual way a personal tribute to our late Mánongs.

After I was to present my comments in English, I would then give the short talk in Ilocano. It was only five short sentences, translated by my neighbor Jessie Blanco, who is also from Narvacan (Camarao). The English part was presented with only a few chokes (actually a hard one when I mentioned my mother), and then I started my eulogy in Ilocano, which I had memorized and practiced in my best imitation of those Filipinos of my youth.

I looked at the audience that filled that large chapel to standing room clear to the back wall, at a fearsome brown sea of staring Filipino faces, practically all Ilocanos… and went into brain lock! I stumbled over some of the tongue warping words I had so easily pronounced in practice. But I was driven by the thought that this was for those Ilocano boys and Lakay Danny’s lodge brothers who were present in spirit for him; I completed it as clearly and firmly as I could. In my heart I knew they would appreciate the opening line that could have been meant for any one of them, especially my father, Sergio (for whom I wished I had done the same):

“Agyámanak únay ití saán nga nagpatínga nga ayát mo nga Áma, Lólo, ken maysá nga Asáwa.”

“I thank you very much for being a loving and devoted father, grandfather and husband.”

Lakay Mariano passed away in January 2009 recalling the melancholy fact that so many of the First Wave’s life stories would never be told, especially for those who never married or had a family to remember them. I sadly gave a eulogy for him, but this time, to make sure those who were there would remember more than just the somber event, I summarized his life story on paper (some of which is repeated here, including the photo above) and had copies distributed.

Hopefully, the eulogy and paper provided a more personal and heartfelt tribute than just words in his obituary column, and maybe all those present would briefly think of those First Wave Filipinos and Filipinas who have passed and…Forget Them Not.

Robert V. Ragsac, Sr. is a retired space systems engineer, having worked in the aerospace and defense industries in various research and project management positions. Residing in San Jose, CA and currently working on a history of First Wave Filipino immigrants who settled in “The Valley of Hearts Delight,” now Silicon Valley.

More articles from Robert V. Ragsac, Sr.