For My Hero, Doc Bien

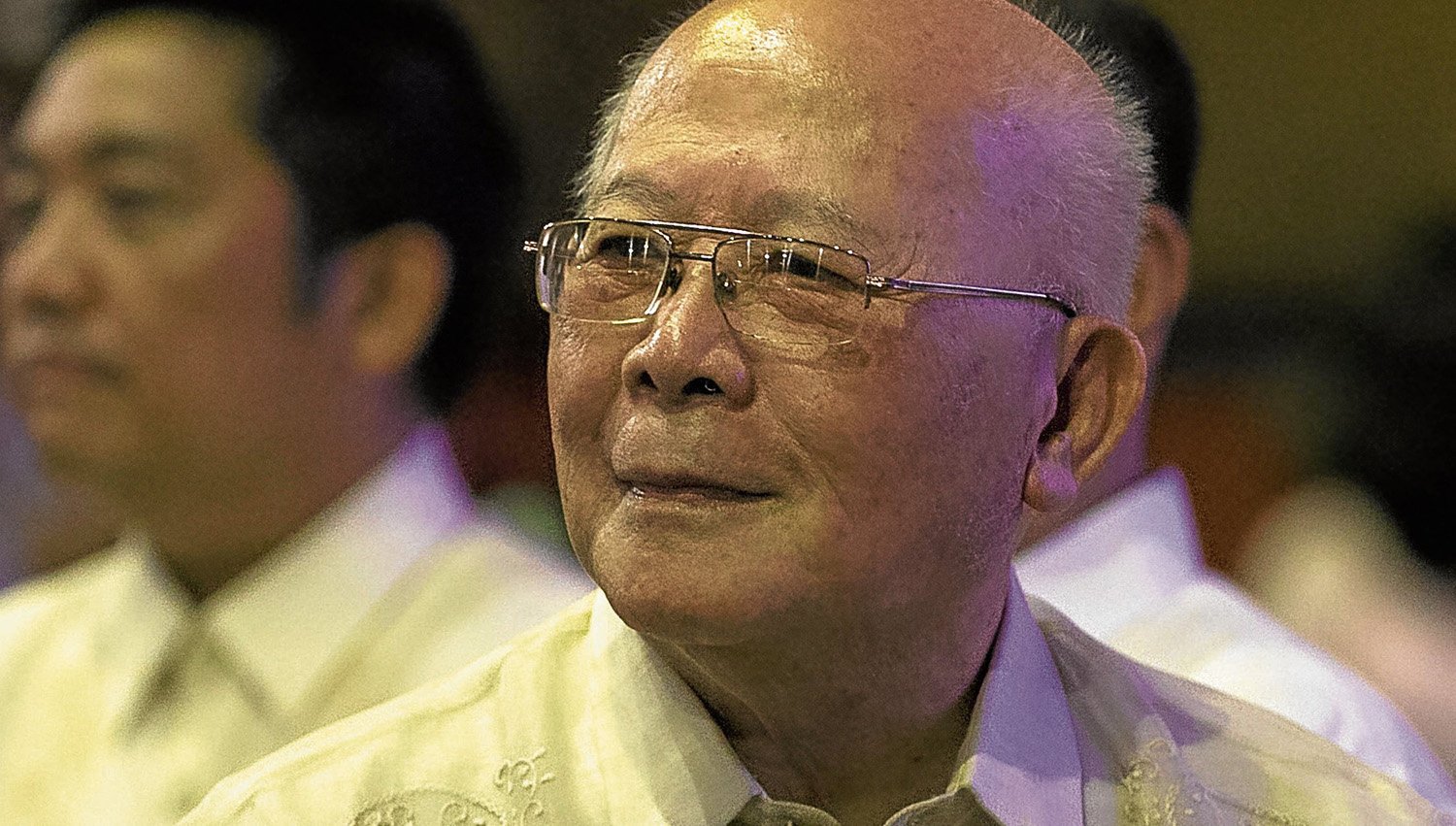

/National Artist Dr. Bienvenido Lumbrera (Source: Inquirer.net)

I was twenty-two when I saw it happen. Bienvenido Lumbera, the man I called “Doc” because he was the first Ph.D I had met in my life, had joined the underground. He was living in what was called a UG house, which kept one out of harm's way but, in the same breath, left one extremely vulnerable. One day, I saw him bring ice cream to another UG house, one where the cultural people—short story writers, craftsmen, playwrights, essayists—stayed. Certainly, you are not a hero because you bring free ice cream. But you are a hero if you bring free ice cream to a house from where you could get arrested and tortured, after coming from another house from where, by every expectation, you could get arrested and tortured.

Bien laid all on the line in the underground. There, every day is life and death. You don’t know if the man selling dirty ice cream is a plant. If the taxi driver you hailed is intel. If the apartment next door is an agents' safehouse. You have meetings, but you don’t know if one of those you're meeting is marked. You buy cigarettes at the sari-sari store, but you don’t know who may be doing reconnaissance by the corner. Everywhere are variables, over much of which you have no control. You just plod on—moving, writing, meeting, bringing free ice cream to comrades.

Dr. Bienvenido Lumbera (3rd from left) with Bodjie Pascua, Carlitos Siguion-Reyna, Bibeth Orteza, Armida Siguion-Reyna, Behn Cervantes, Ishmael Bernal and Lino Brocka (Photo courtesy of Leon Gallery)

Why? Because you are in the middle of a huge battle against a very bad guy, a wholesale dictator.

An academic like Bien—who has always tooled with facts, who verifies, who likes showing proof—now has to produce fake identities, calling himself Angel, Celo, even Paksa. I wonder to myself: What philosophies did this man of letters and the arts turn to? What principles did he lean on to keep himself steady? What rationalizations did he use to stave off thoughts of mortality? And that doctorate it took ages to earn—where goes the potent career, now blunted, now run askew? where goes the writing and the music in flight, now circumscribed by a singular cause?

If the man wavered, I did not hear about it. But I imagine Doc reining in what doubts disturbed because, quite simply, the times demanded he do so. That is selfless, that is heroic.

“I never did find out how much Bien was brutalized. I gather that heroes do not go around talking about their scars. Easy conversation, it does not make.”

For ten days and nights, we were incommunicado in Camp Aguinaldo—Bien, Flor, Ricky, Sarsi, Bobby, and I. In the hub of the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP), we were isolated from each other, summoned, ringed in by intelligence agents. To this day I firmly believe that the reason the rest of us left the place relatively unscathed was because Bien, marked by ISAFP as leader of the pack, bore the brunt of the interrogation. Flor and I, from the tiny back bodega we were locked up in, could see Bien led from his cell and handed to Colonel Arcega. In the darkness, with a slice of moon, we could see the bespectacled Bien flanked by muscled operatives. I no longer recall with certainty but, in my head, his hands were tied. Between Flor and I, no word passed. We might have imagined the humiliations to befall him—but, no, it did not bear thinking. We spent the night in quiet. We would learn later that Bien admitted to whatever crimes they threw at him. Operatives found letters in the UG house, and they wanted to know the persons appearing constantly in these, most particularly an STR. STR was everywhere; he must be a big catch. Bien owned up to being STR. He just decided this was more painless than convincing them STR was a standard salutation among comrades: Sa Tagumpay ng Rebolusyon! (To the Victory of the Revolution) (In fact, it was.) Again, Bien admitted to being Charlie or some such name appearing in another letter. He got lucky. The operatives did not see another letter where the same Charlie says, “Kapapanganak ko lang (I’ve just given birth).”

I never did find out how much Bien was brutalized. I gather that heroes do not go around talking about their scars. Easy conversation, it does not make. For there is a rage that stays inside—hidden, veiled, buried—in anyone who is violated that only those who have known violation truly understand.

When the incommunicado period was suddenly over, we were brought across the street, to Camp Crame, and presented before the Judge Advocate General's Office, or JAGO. At least two judges in pressed uniforms were perched on a dais and looked down at the five of us who had not bathed for days. They were asking what I thought was a very silly question: “Why are you here?” We looked at each other but had no answer. Now, we weren't an extraordinarily dumb group. We were writers, we were teachers, we could hold our own, I wager. And in that moment, we knew enough not to provoke judges. Still, somebody had to step up. Bien did. He answered for us, although I don’t remember what he said exactly, maybe something absurd, like “We’re here on subversion.” Whatever it was, the judges must have been satisfied because soon they dismissed us.

We were brought to Fort Bonifacio's Ipil Detention Center next. There, the man with a doctorate in comparative literature from the University of Indiana did nearly a year of gardening, macrame, kitchen/toilet/bathroom duty, and everything else others did who were far younger and lighter than him. Like, hauling pails of water from drums standing meters out in the yard to bring to 12 toilets used by 300 male detainees.

He was an intellectual navigating life. A gentle being functioning as hardcore comrade. He was, for instance, part of a plan to bolt six prisoners out of Fort Bonifacio. It was a plan that succeeded, too. One of the six is with us today, Judy Taguiwalo, whose story and the stories of those who escaped with her, Lorena Barros being one of them, are narratives Bien knows very well.

Our tendency, I dare say, is to keep things cheerful when we recall for others the hard days of martial law. We prefer to dwell on the funny and the nice. And so, we remember the time the Circus Band performed at the Ipil mess hall because they wanted to entertain Doc, their Ateneo professor. And the times we played volleyball and badminton in prison, accommodations we fought to get. And the time we launched a hunger strike where we, women detainees, climbed the roof and flew a cloth like a flag and acted like we'd been shot and crying freedom, while sentries at their towers grew steadily more alert. Bien knew these stories very well, too.

The author's UG group held a reunion on March 19, 2019 on the occasion of Ricky Lee's birthday. Left to right: Flor Caagusan, Diego Maranan (the son of former detainees Aida Santos and Ed Maranan, representing his parents), Cesar Carlos, Jo-Ann Maglipon, Ricky Lee. Seated: National Artist Bienvenido Lumbera.

But on a plaintive day, one knows that prison takes away, not just time and freedom and justice, it takes away happiness. It messes with your thoughts and feelings. It deprives you of certainty. You are not dead—but are you alive? There is no romance to being a political prisoner. There is only the heroic act of staying alive. And if, years after, you get back to being productive and literate and fulfilled and, happiest of all, you witness the dictator scampering from the palace, you glimpse a bit of your heroism and feel some of your triumph. You can pause. But when one day another very bad guy rises, one more wholesale dictator, you reach inside you once more—and get into the middle of the huge battle once more. This is not wishful thinking. Doc Bien did it, again and again.

Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon started her journalism career in 1972, the year Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. After joining the Underground and going to prison, she returned to the trade, where she remains today, as editor and author.

More articles from Jo-Ann Maglipon