Finding Filipino in San Francisco’s Bus Stops

/The “Finding Filipino” Series on Market Street in San Francisco (Photo by Raymond VIrata)

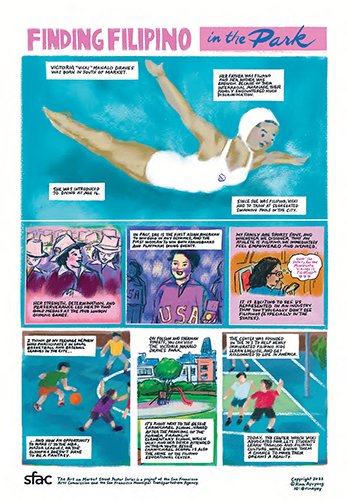

Finding Filipino was the second among this year’s four commissioned poster installments under the Art on Market Street Poster Series Program by the San Francisco Arts Commission (SFAC). The theme was “Comics 2.0,” a continuation of the 2022 poster series based on the artistic medium of comics.

Finding Filipino comprised nine comics vignettes that commemorated the rich history and legacy of Filipinos in San Francisco:

“Filipino Beginnings in South Park”

(Source: SF.gov)

“Empowerment and Activism in Manilatown” on Kearny Street

(Source: SF.gov)

“A Park for an Olympic Champion” honoring Victoria Manalo Draves

(Source: SF.gov)

“Art and Community Organizing in the South of Market”

(Source: SF.gov)

“Pistahan at Yerba Buena Gardens”

(Source: SF.gov)

“Filipino Focus in the Mission and Excelsior Districts”

(Source: SF.gov)

“Aunties in the Avenues” honoring the Filipino community on Geary Boulevard

(Source: SF.gov)

“Parols and Adobo in the Financial District” “Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University (SFSU).”

(Source: SF.gov)

Rina Ayuyang says Finding Filipino in different ways and types of communities in San Francisco is what she wants to focus on. “I’m excited about all the opportunities to talk about our story and history.”

Rina Ayuyang

Rina’s supposedly normal American childhood during the Reagan years was upended by the realization that it was unusual to be Filipino. She had always thought that she came from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Technically, this is true. After all, it is where she was born. “In an early age, you just think that this is where you’re from and this is who you are.”

She grew up in a predominantly white working-class suburb, in a house filled with various objects and decor from the Philippines. Her mother said that it was to remind them of where they came from. “I thought that the wood carvings and everything that made us Filipino was something that was universal."

She found out fast that not everyone had a large wooden spoon and fork hanging on their wall, or a carving of a carabao or a bulul (rice deity) in their living room. She also realized that hers was the only Asian family in their neighborhood. “That’s when I really found out that I was different. That I came from someplace else. That was how I found out that being Filipino was not usual where I lived.”

Rina’s family history in the United States coincides with major waves of immigration in Filipino American history. It began when her great grandfather and grandfather immigrated from Ilocos Sur to San Francisco in the 1920s, becoming part of the Manong generation. She also has family members who worked in plantations in Hawaii as well as farms in Seattle.

Her grandfather joined the Army and was able to sponsor her parents to come to America in the 1970s during the third wave of Filipino immigration. Her mother, a pathologist, found her first job in Oakland where Rina now lives. “It’s like a full circle moment.”

Eventually, her mother received a medical residency at the University of Pittsburgh, which was how her family came to Pennsylvania. Rina is the second American-born among four children.

Like many Filipino Americans of her generation, Rina and her siblings were pushed by their parents to assimilate into American culture. Informed by the history of discrimination faced by Filipinos in America, they thought that it was best if they conformed.

“For it not to be something that was going to be an extra hardship for us in order to survive and thrive in America.” She is part of a generation of Filipino Americans who were not taught to speak their native language. “They wanted us to be focused and have a normal, whatever that is, ‘American’ childhood.”

Being the only Asian in grade school was a challenge. “I was usually the only Asian in the group, so it was hard to really celebrate your being Filipino because you had to assimilate to life in Pittsburgh, trying to down play your otherness. It was hard to embrace that outside of your family.”

Things became better in high school when she came across other Asians on campus, but she was not “really thinking too much about being Filipino” in order to relate. “We all had to band together as Asians. It was sort of like trying to find your tribe but also we were all different people.”

Rina found solace from the outside world that constantly reminded her of her “otherness” through a small Filipino community made up of families that were friends of her parents. The homes of these Filipino families also had objects from the Philippines like the ones found in her own home.

After graduating from high school, Rina went to San Francisco and pursued an art degree at San Francisco State University. It was a revelatory, empowering, and liberating experience.

Surrounded by a diverse population, she felt for the first time how it was to be “just a normal human being. It was kind of a culture shock. It’s a totally different feeling.”

It was the place that she realized that she could be whatever she wanted to be, that she could be an artist. "It’s just really powerful to be in San Francisco and to know that this history is there. To be a part of that is exciting.”

Drawing was something that Rina loved to do from an early age. She also loved reading comics in the Sunday paper. “I’ve always loved Peanuts and Nancy. I just love humor that’s found in comics. Filipinos also use humor to tell traumatic stories.”

She recalls how her lola and lolo would come over to their house to babysit her and brought magazines from the Philippines such as Liwayway, which had serialized Filipino comics that her lola would translate for her.

But her all-time favorite was artist Larry Alcala and his Mang Ambo and Slice of Life comics. “I’m very drawn to everything he did.” Alcala’s way of laying out his comics and his subject matter inspired Rina’s own comics art. “They’re like documents of where you come from. It’s just so much fun to look at.”

Rina’s sister influenced her to practice drawing and painting and follow a career in art.

She dabbled in painting after college, but everything changed when she came across independent comics from the likes of Adrian Tomine and his Optic Nerve and Lynda Barry.

“I loved what they were doing with comics. I loved how Lynda Barry talked about people with their regular lives and her autobiography. I loved how they were using the medium to tell stories like that.”

Rina was never a super hero comic book reader although, she appreciates the art that goes into that and all the Filipinos that did art for Marvel and DC. But those stories never resonated with her.

Her love for the storytelling and realism of independent comics artists and her painting background are major elements in her distinctive style. Her comics have always had an autobiographical element. “I’ve always been talking about where I’m from, my family, and the high jinks that go on.”

Rina’s commitment to telling her Filipino American experience and history has culminated in her Finding Filipino series.

“I think this series is really wonderful. I like that she blended history in a very personal way,” says Craig Corpora, program associate, Civic Art Collection and Public Art Program, SFAC. He adds, “The posters were told in this first-person perspective and they are imbued with this local history which was such a great way to approach things. It doesn’t seem didactic. It has this personal touch.”

Craig Corpora, SFAC

The public’s response to the Finding Filipino poster series has been encouraging, and Rina is currently working on ways to make Finding Filipino available to the public in a smaller format.

Last May, she released to critical praise her third comic book, The Man in the McIntosh Suit, “a Filipino-American take on Depression-era noir featuring mistaken identities, speakeasies, and lost love.”

Rina thinks that she has found the Filipino through the history, legacy and community in San Francisco, but she also acknowledges that there is so much more to learn and eventually share through her art.

So, Finding Filipino is an ongoing process of learning. “We’re still trying to find our way, to honor where we came from. We are a community that is still trying to find pride in who we are. We need to continue to have stories out there that center on our community and our history.”

Wilfred Galila is a San Francisco Bay Area-based multimedia artist and writer.